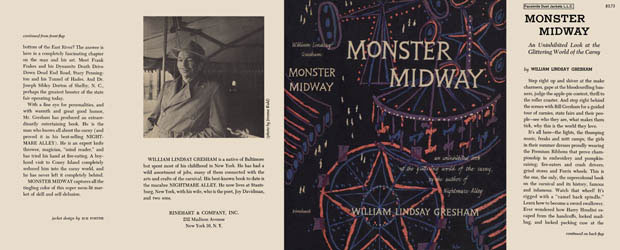

Monster Midway: An uninhibited look at the glittering world of the carny

William Lindsay Gresham (1953)

I came in with a second burst of ignorance. "Wait a minute, Clem—how do you find guys that will do things like that? I mean, biting the heads off chickens. Good God, man, do you find a guy doing that behind a barn somewhere and ... ?"

The Ipecac took another punishing. Clem shut one eye and looked at me in conspiratorial fashion. "'Kid, you don't find a geek. You make a geek."

"But how?"

He drew his chair a little closer and lowered his voice, although outside our improvised infirmary the town was as black and empty as the coalbin of a haunted house; the only sound was the distant boom of Mussolini's bombers, pounding the port of Valencia to bits.

"When you get hold of one of them fellows, he ain't a geek—he's a drunk. Or he's on the morph. He comes begging for a job. You tell him, "Well, I ain't got anything regular, but I got a temporary job. My wild man quit on me, and I got to get another to fill in. Meanwhile you can put on the wild man outfit and sit in the pit and make believe you're biting the heads off chickens and drinking the blood. 'Course you won't be biting the heads off. You'll have a razor blade hid in your hand, and when you pick up the chicken you'll give its neck a slit and let the blood run down your chin. "Mind, it ain't a good job, but it'll give you a place to sleep ... "

"When you get hold of one of them fellows, he ain't a geek—he's a drunk. Or he's on the morph. He comes begging for a job. You tell him, "Well, I ain't got anything regular, but I got a temporary job. My wild man quit on me, and I got to get another to fill in. Meanwhile you can put on the wild man outfit and sit in the pit and make believe you're biting the heads off chickens and drinking the blood. 'Course you won't be biting the heads off. You'll have a razor blade hid in your hand, and when you pick up the chicken you'll give its neck a slit and let the blood run down your chin. "Mind, it ain't a good job, but it'll give you a place to sleep ... "

"Well, he takes it. You see, with a real rummy, he figures anything is better than being without a bottle. And if he' s on morphine, he'll turn himself inside out to keep from getting 'in a jam'—caught short without a dose. One of them fellows gets in a jam and he feels like all the nerves in his body have turned into live ants and all of 'em biting at once.

"Well, you let him go on, faking the geek for a few days, and you see that he gets his bottle regular. Or his deck of 'M' so he can bang himself night and morning and keep the horrors away. Then you say one night after the show closes, 'You better turn in the stuff and hit the road after we close tomorrow night. I got to get me a real geek. You can't draw no crowd, faking it that way.' You slip him the bottle and you tell him, 'This is the last one you get.' You tell him that. He has all that night and all the next day to think it over. And the next night when you throw in the chicken—he'll geek."

I was stone-cold sober.

Clem rattled on with his recollections of that season, and they had to do with a fickle babe, rain and an absconding partner, but I wasn't listening to him. I was paralyzed by his account of the geek-manufacturing process. And I remembered Kuprin's summary of prostitution: the horror of it is that among the girls there is no horror.

Full-blown, the plot for a story leaped into my head: a man learns, from working in a carnival side show, that a geek is made by exploiting another person's desperate need. Taking this as his guiding principle in life, he rises higher and higher, finally meets someone who works the same process on him, and tumbles back literally into the pit—biting the heads off chickens himself for a bottle a day. (14-16)

A carnival is one place where eccentricity is not punished as it is in the anthill life of the big corporations. In fact, if your eccentricity is colorful enough—such as being fascinated by fire, or having a passion for getting tattooed—you can make it pay off. (16-17)

Carnies are made, not born. I have never known one whose parents were carnival people. In all cases, the original lure was the same: to get away from the deadly routine of farm or factory, or occasionally from the restrictions of a school like Groton or Exeter. Thoreau's famous line, that most men lead lives of quiet desperation, finds one answer in the carnival where steady rain or continued bad business may produce moments of desperation but no one has to be quiet about it. The worse things get, the louder a carny talker turns up his amplifier and the harder the girls in the show wiggle their tails. (17)

There's another priceless truth which can be learned from carnival folk: don't knock yourself out no matter how hard you have to labor. To handle the front of a show, making one opening after another, from morning to night at a big agricultural fair, requires a type of inner relaxation that all real carnies have. The cultist Gurdjieff taught his disciples, "Don't grab after things; let things happen." The carnies knew it all along; they learn it their first season "with it." (18)

Optimism, disguised under traditional growls and beefs, is rampant on the midway. "Ah, hell, it can't rain forever," is a sustaining slogan, whether you are a carny or not. (19)

As a microcosm, the carnival vibrates at a faster rate than the larger world. It is a mosaic of sex, danger, skill, curiosity, competition, noise, color and excitement. You get out of it what you bring to it—fun or trouble. (20)

After the contest everybody in the grandstand crowd who liked square dancing got out on the race track and took part in what Dorton describes as a "king-sized sukey jump." (46)

The manufacture of a ride for the proletariat, featuring horses carved of wood, goes back a long way. Mule power eventually replaced manpower in operating it; later steam engines took over. The rise and fall of the horses, simulating a slow canter, came in a little over a hundred years ago, the invention of a New York Stater, memorable both for his contribution to the joy of childhood and the Biblical thunder of his name: Eliphalet S. Scripture. (54)

Carnival rides are much safer than they look. They are built so that even if a passenger is drunk and tries to stand or clamber around, he can't do anything to endanger himself or his fellow passengers. (57)

. . . on through the roughhouse centrifugal torture devices of the Looper and the Octopus. . . . (58)

"You'd think when somebody takes a bad spill that the crowd would holler and the women would faint," Earl comments with the slightest trace of bitterness. "But not a bit of it. Most of them just watch as if this is what they paid to see. And maybe it is, at that." (78)

With one of Gene's ten-inchers I succeeded in driving a Greenwich Village landlord into a fine tizzy.

The air-shaft neighbors were robbed of their rest by a rhythmic sound: Tock. Tock. Tack. Clang-blam! (Missed .) And when I finally consented to move, the wall of the cubbyhole apartment was pocked with a multitude of little gouges. How they got there would be a mystery to anyone who has never caught the fever and tried to use a six-inch square of wood for a target. People either understand knife throwing or they don't. (87)

This is the whole secret of throwing knives: holding fingers and wrist rigid and judging the distance. I have seen many professionals on the midway use a wrist flip, but they simply made it a hundred times harder for themselves. (88)

[Dwarves'] psychological problem differs from that of the midget. No one ever mistakes a dwarf for a child, and it seems easier for a man to resign himself to being thought ugly than for him to be considered "cute." (99)

In the end, you will probably discover for yourself, the hard way, that people fall into a few basic categories, that their lives are pretty much the same, although they all think they are different from other people, and that basically human life presents much the same problems to us all. Given this amount of savvy, and the ability to get along well with women, and you're fixed for life—as a mitt reader, card reader, head feeler, crystal-gazer or "receiver of cosmic vibrations." You have the basic formula of the "cold reading" and once you have that, plus a few years' experience, you'll never starve. (119)

To paraphrase an old Broadway ballad:

Some ladle out the blarney in the mitt camp of a carny,

Some lecture on the Cosmic Oversoul,

But their names would be mud, like a chump playing stud

If they lost that old ace in the hole. (120)

Very much compressed, the cold reader's breakdown

of types and their problems runs something like this:

I. Young Girl

A. Wild type

-

I can't catch the man I want.

-

I can't hold him.

-

My conscience is bothering me.

-

I'm pregnant.

B. Home Girl

-

I'm afraid of men.

-

I'm afraid of life and responsibility.

-

I'm afraid of Mom.

-

Won't anything exciting ever happen?

C. Career Girl ( usually jealous of a talented or successful

brother )

-

(under 25) I'm ambitious; I hate and despise men and marriage. Will I be

a success?

-

(over 25) I'm panicky. Will anybody ever marry me?

II. Mature Woman (30 to 50)

A. Still wild

-

Why isn't it as much fun any more? I'm lonely.

-

I'm afraid of getting my face scarred or burning to death in a fire (This

never misses.)

-

I've got to believe in something -- the occult, a new religion that doesn't

include morals, or in you, the fortuneteller.

B. Wife and Mother

-

Is my husband seeing another woman?

-

When will he make more money?

-

I'm worried about the children.

III. Spinster

A. Still presentable

-

When will I meet him?

B. Given up hope.

-

My best friend has done me dirt.

-

I'm crushed -- a gigolo got my savings!

IV. Young Man

A. Flashy type

-

Is there a system for beating the races?

-

What do you do when you get a girl in trouble?

a. Is she really pregnant or is she playing me for a sucker?

B. Good boy

-

Will I be a success?

-

How can I improve my education?

-

Should I join the Navy, Marine Corps, etc.?

-

Is my girl two-timing me?

a. She's mixed up with Type A.

-

I'm afraid of Mom!

V. Mature Man

A. Wolf, married or single

-

Girl trouble

a. I can't get her!!

b. I can't get rid of her!!

c. Her husband is after me with a .38,

d. Does my wife know?

-

2. Rubber-tire-around-the-middle: is there anything to this business of

monkey glands or hormone shots? I'm ashamed to ask my doctor.

B. Businessman

-

Where's the money going to come from?

-

Will this deal work out?

-

Did I do right in that deal?

-

What does my wife do all day?

VI. Elderly People

A. Woman

-

Will my daughter get a good husband?

-

Will That Creature be a good wife to my son?

-

Will the children (or grandchildren) be all right?

B. Man

-

Will I ever have enough money to retire on?

-

I'm afraid to die.

C. Both

-

Am I going to need an operation?

VII. Wise Guy

A. Toughie

-

I'm here for laughs. (Ease him out quick.)

B. Defensive bravado

-

I'm smarter than most people: I see through you. (Flatter him; he'll end

by eating out of your hand.)

This, needless to say, is not all there is to human nature, but it is all

most people bring with them to the mitt camp. The cynicism of this analysis

is for the cold reader's private benefit. What she actually tells the sucker

is full of the milk of human kindness. (123-6)

"I started off with a routine opening, rattling it out quick and in

a low tone of voice so she would have to strain her ears to hear me. This

keeps her from tightening up and putting on a deadpan to try and fool me,

just in case she was skeptical. If a customer is using all her effort to

hear what you say, she lets down her guard. I always begin, 'My dear

girl, I am glad you have taken this opportunity to consult me, for I feel

that I can be of help. You understand of course that I make no claim to

occult powers and do not predict the future in any way...' This is

a stall, just in case she turns out to be a cop or some kind of an investigator.

Not that it worries you when you are working on a midway because the cops

have been 'seen' already on account of the games and girl shows. And if

a town is really hostile -- having a shake-up in the police department

or something—the word goes out and you tone down everything. It isn't

the public that want it that way, it's the people who are going to give

the public what's good for it or bust every bone in their heads." (128)

But the East Indians were not the only snake handlers. In our own Southwest the Snake Fraternity of the Hopi tribe, every other August, dance with a frenzied shaking of tortoise-shell rattles while holding in their mouths, by the middle of the body, the active little rattlesnakes of the desert called sidewinders. After the ceremony the snakes are carefully liberated in crevices of rock leading into the center of the earth, carrying with them the prayers of the Hopi to the rain god in his underground kingdom.

Scientists had lain in wait when the snakes were released and found them in full possession of their fangs. Yet no snake priest of the Hopi ever died or seemed to suffer a bad bite. Lo! How? (140)

The secrets of the Hopi Snake Society might have remained undiscovered forever had not an educated Hopi who had been converted to Christianity blown the whistle on his former coreligionists. According to him, in the kiva, or sacred room of the cult, the snakes are washed and "prepared" for the ceremony. And this preparation consists of teasing the sidewinders, making them strike repeatedly at the warm liver of a freshly killed prairie dog. Every strike squeezes out more venom until at last the glands are nearly empty. A few minutes later the snakes are brought out and the dancers seize them by the body—taking care not to squeeze them too tight—and hold them in their mouths. Man does not bite snake, but keeps the rattler's attention occupied with the "snake whip"—a stick with eagle feathers on the end of it. Whether the sidewinders sense their impotence in the temporary exhaustion of their poison and so do not strike or whether the constant movement of the dancers keeps them "off balance" and confused is not known. A few hours after such a "milking" the poison sacs are full again, but by this time the snakes have been released to act as messengers to the rain god—or possibly to be recaptured by herpetologists trying to find out the secret of the snake cult of the Hopi.

After a few years of lurid publicity, there was a schism in the snake cults of the South; they broke into two separate sects, the Signs Following and the Holiness Faith Healers. Charges and countercharges flew hot and heavy, each group accusing the other of "milking" their rattlers before the services. (144-5)

At her private zoo on the West Coast she had one sixteen feet long, named King. It was the taming of this monster which won Grace Wiley the reputation of being the greatest handler of poisonous snakes who ever lived.

Mrs. Wiley told me that she had become interested in snakes through having to overcome her fear of them on field trips as an entomologist. While curator of a natural history museum in Minneapolis she made friends with a rattlesnake and decided that poisonous snakes could be tamed like many other wild animals. "When I had kept rattlesnakes for several years I found they were responsive to kindness," she told me, with a crusading glint in her eye. "Then I got a cobra. I fastened a turkey feather to a dowel stick and would reach into his pen and stroke him with it every day. Snakes love being stroked. He would lie still and let me pet him with the feather by the hour. Every day I cut a half inch from the stick until I was holding the turkey feather in my fingers. Then I cut off a little of the feather each day until I was stroking the cobra with my hand. Patience and good will are all that's needed. Soon I had him used to being touched, and I found that I could pick him up and hold him in my lap with perfect safety." (146-7)

[Herb Nichols's] taming process consists of getting into a pen with wild ones, wearing a pair of rubber-bottomed hunting boots. When he comes too near, a snake will strike out at the shoes again and again. The soft rubber doesn't hurt their mouths and they come to realize, in time, that striking at Herb gets them nowhere. This is an interesting problem in animal psychology for most herpetologists agree that snakes have nothing resembling "intelligence." They can, however, get over being frightened and grow accustomed to certain individuals. They also seem able to detect fear in humans—they get nervous in the presence of a person terrified of snakes. Gradually Nichols eliminates the bad-tempered individuals and specializes on the mild-mannered ones. He gets them used to his hands and finally is able to pick them up. Here he has an advantage which has saved him trouble time and time again, both in his taming pit and the wilds—his reflexes are so fast that he can jerk his hand away from a striking rattler before his conscious mind ever perceives the lightning thrust of the head. (151)

"I always warn amateurs not to try it before they have spent several years in study. For instance, it is possible—risky but possible—to pick up a wild rattler by distracting his attention with one hand while reaching around behind him with the other and pouncing down on his neck. But you don't want to try this system on the cottonmouth. A rattler can't see directly over his head—his food travels along the ground. But the cottonmouth makes his living by lying on a stream bed, watching for fish swimming over him. He can see straight up." (152)

In the average crime show there are blowups of photos showing riddled gangsters, victims of lynchings and anything else the proprietor can get together and the public will stand for—which is considerable. A full-sized model of an electric chair or the actual bullet-perforated car in which some gang lord met his end would put a crime show in the very top brackets of its field. (162)

There are three things which a sampling of public opinion shows will enrage the American male above all others—cruelty to animals, cruelty to children, and finding a hair in his food. The first two are taboo on the midway. As for the third, in the cookhouse you've just got to take your chances, Mac. (163)

"What happened to the figures?" I asked her. Some of the victims, after seven years or so of continued torture, were beginning to crack around the ears, revealing gray papier-mache underneath. Some of their wounds seemed to be bleeding excelsior.

Oh, we took a beating in a big blowdown earlier in the season," the fair ticket seller assured me. This I could believe, but the torture victims had had a hard life nonetheless, having been on the road for years. And when any carnival attraction begins to show excessive wear and customers complain about it, a blowdown is sometimes blamed for it. After all, it's logical and it's dramatic. And drama is something you gotta have, whether in your show or in your alibis. (169)

The underlying "gaff" of rope ties and strait-jacket challenge escapes lies in expanding the chest, flexing the muscles and bringing subtle tensions to play between the anus in order to secure the precious "slack" necessary for one's first attack on the restraint. This system is familiar to all who have ever spent much time around horses—they are masters of it, swelling up their bellies as the saddle girth is tightened. (182)

The master locksmith of New York, Charles Courtney, knew Houdini and worked with him, gimmicking up some difficult padlocks which Houdini would switch for locks of the same make sent up by challengers. Courtney claimed that Houdini was no master locksmith, and it is hard to see how he could have been one since the knowledge of locks possessed by a man like Courtney takes a lifetime to acquire.

Courtney had an unbelievable talent of his own. He could cut keys from memory!

A friend of mine once did an interview with him, during which Courtney asked, "May I see your key ring?" It was handed over, examined carefully and passed back. The lock master then went over to his work bench and cut half a dozen keys. He returned to my friend, handed him the new keys and said smilingly, "Now you have a duplicate set." He had remembered the notches on half a dozen Yale keys and cut them perfectly without referring again to the originals! This sort of "wild talent" would have been a treasure to Houdini. (189)

However, before getting down to the business of fire-eating as a profession I am willing to disclose my own arcane method of staying out of trouble: when a guy reached that point of drunkenness at which he wanted to knock my block off just because I happened to be there, I would blow up in his face, my anger directed not at him—perish forbid—but at some comfortably unpopular subject: prohibition, unemployment, political corruption in the national government or even the weather. He would be delighted to find a safe subject for his abuse, and we would be pals from then on. The idea was to join forces against a common enemy. In later years I learned to my chagrin that my precious secret is the heart and soul of demagogy and is the real meat of the aphorism that "patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel." Still, it was an angle and I have always been a collector of angles, just in case. (196)

There is a type of mind which feeds itself on the disparagement of others, complaining with smug bitterness when it learns the modus operandi of a magic trick, "I knew there was some trick to it; probably childishly simple."

That type of mind has no business at a carnival; it should sit home and contemplate its own cleverness. The way to have fun at a carnival is in humility, to cultivate a sense of wonder. I am grateful, indeed, that I have never lost this faculty. Even though I know how some of the tricks are done, I believe in relaxing and enjoying them. You get more for your money that way. (196)

When I was a very small boy I was teased by my father into summoning enough nerve to pass my finger quickly through a candle flame. Sure enough, it didn't burn me just as it didn't burn him. My eyes told me that it was safe, as long as you kept the finger moving, yet fear prevailed until he kidded me into trying it. Also he had another trick which I eventually mastered—he would light a kitchen match, throw back his head and place the burning tip of the match in his mouth, closing his lips around it to extinguish it. His secret was to keep blowing gently, exhaling with a sharp puff just before closing his mouth. With these two simple experiments I had grasped the essential principles of fire-eating without realizing it. (196-7)

The principle of fire-eating is simple enough. The only trouble with the act is that you mustn't make a mistake. (198)

Much of the art of the side show lies in the use of little-known natural laws. There are, for instance, areas of the body where the nerves recording pain in the skin seem to be sparser than in other spots. The shoulders are one, the inside the forearm is another. If you take a hatpin and touch the point of it to the inside of your forearm up near the elbow, pointing away from you, and keep shifting the point a fraction of an inch each way, after a few tries you will find a lot much less sensitive than the others. Now if you give the skin a quick jab it will penetrate the skin, sliding in almost parallel to it. Keep pushing and the point begins to come out the other side, first as a long, slim finger of flesh, then it breaks into the open with a sharp nip. Leave it there a moment. Now you are a human pincushion. (203)

Early in the game thrill-show operators discovered a trait of human nature which has been accommodated ever since—people can stand just so much tension and then they have to discharge it in laughter or they grow apathetic. Laughs are spaced strategically through the performance by the thrill-show clowns. (209-10)

Johnnie frowned for a moment. "The first thing to remember is that you're likely to get skinned up some whatever you do. I'd say the best thing is to draw your knees up and go limp—just turn yourself into a rag doll. That way you won't make your feet a fulcrum which will lever your body up in an arc and hammer your head into the roof or the windshield. The figures show that a passenger in the back seat who is asleep has a better chance in a bad crash than if he's awake and sees what's coming and gets tense. It's like in a thrill show, doing a head-on crash—you slide over into the back and you keep steering and feeding gas with the wire. At the last minute you drop down on the floor behind the pad and just go limp." (229-30)

Time after time, advance publicity on a crash would draw a warning telegram from Washington such as:

DEPARTMENT CONSIDERS INTENTIONAL CRASHES EXTREMELY HAZARDOUS AND DOES NOT WAIVE ANY OF ITS REGULATIONS TO PERMIT THEM

INSPECTION SERVICE

The hand of government is self-evident in these warnings; all could have easily been said in ten words but eloquence was more characteristic than economy. Besides, the wires were sent collect. (242)

Loops, tailspins, leaf falls, barrel rolls—across the landscape of America the Frakes Flying Circus made its way, dodging indignant federal inspectors and plowing through a gnat-swarm of state laws and local ordinances. (243)

There is a stock interview question: "Have you achieved your life's ambition?" which can draw torrents of pointing-with-pride from a politician or touch off an explosion of bitterness from a neurotic artist. Just for fun I heaved it at Frank Foster Frakes.

He said, "When I was a kid I always wanted to show off. Well"—he took another swallow of Carol's good coffee—"reckon I showed off." (258)

Working the quarter count requires no skill at sleight of hand. The customer offers a fin for change. You take a handful of quarters and count them into his hand like so:

"One, two, three, four—one dollar." Pause. Then, with four more quarters in action you continue, "A dollar twenty-five, a dollar fifty, a dollar seventy-five, two dollars." Pause. Then, "One, two, three, four . . ." and your hand goes into your pocket for more coins, making a break in the pace. Finally, you bring out another dollar's worth of quarters and finish up, "Four twenty-five, four fifty, four seventy-five, five dollars." I have done this over and over, demonstrating it to lecture audiences, before anyone caught wise. And if the victim does decide to count his handful of quarters, the change maker is ready for him, bringing out a folded dollar bill and saying, "I'll have to give you a bill for the last buck, okay?" (260-1)

The "fix" is put into the local cops. The carnies don't ask for it; they don't have to. The cops hit them for it. In most places the cops have to be "seen" whether the games and girl shows are running "strong" or not. If you have to pay off anyhow, why not make a dollar? is the carny philosophy. The local law has been known to "slough" the wheels—raid them and close them up. This usually happens on a Monday night, when the play would be measly anyhow. The news that the wheels on the midway have been raided always gets space in the local paper, bringing a good crowd out Tuesday night to play them, figuring that the carnies will be scared off of any monkey business. That time they can really go to town. (262-3)

The principle of the midway games is basically that the house must have a high percentage in its favor or it couldn't pay the carnival management a big fee for midway frontage week after week. You would think anybody could understand this, but the majority of people who like to gamble never think of it. The roulette wheels at Monte Carlo and Reno with their two house numbers have the same advantage, and no matter how elaborate a martingale system you figure out, the house will get your bank roll in the end, if you play long enough. (271)

There are many theories in answer to the question, "What makes a man become a magician?" If he simply loved applause he might learn to sing, dance, recite or play a musical instrument. The average amateur spends about one percent of his magic-time in actual performance in front of an audience. The rest of it is taken up in thinking and talking about magic and in countless hours of practice before his bedroom mirror. Why does he do it?

The obvious guess is that he is acting out a fantasy of power; he is making his daydream of being a superman come closer to reality than most of us bother to do. (283)

France had reluctantly colonized Algeria as the only answer to the piracy problem; her hold on the Barbary coast was precarious and was constantly threatened by agitation of the marabouts who preached holy war against the roumi (a native word for Christians, which was accompanied by spitting). (284)

Undue modesty is a great handicap in a showman; the great Robert-Houdin was never afflicted with this character defect. (286)

In 1890, a performer billed as Deline was doing a version of William Tell with an apple on a boy's head; and with a ghastly result—he killed his own son. (287)

There was nothing glib or smooth about Annemann the Mentalist. The nervous swaying of his body, the sweat rolling down his face, the tension of his voice as he pounded his forehead with his fist, urging the spectator to concentrate on the number of a dollar bill—all were signs either of great acting or of some genuine inner strain, a gigantic effort of will.

It was no more acting than it was telepathy. The strain was there: Annemann, the Enigma, was battling stage fright! (294)

All this is just what I might have expected but a lot of other things have come up that are harder to take. I always thought carnies were just show people but they're not. That is, the people who work the "front end"—where all the games are on the midway—are the toughest kind of people, always trying to skin somebody out of a dime. They seem to live in a world of their own. They don't know anything about any other world. During the winter they live with other carnies down in Florida and summers they are on the road. You can't talk to them about anything except carny. (303)

Dear Mom:

Not much on writing as you know but I know how you worry about your wandering boy. Mom, you got nothing to worry about. I'm doing okay. The only time we really have to lay in the collar and pull is when we move and that's only on weekends. Don't tell Pop but this beats farming all hollow.

[...]

Honest, Mom, I never regretted for a minute coming on this show. It's swell.

Your affectionate son,

Wayne (306)

|