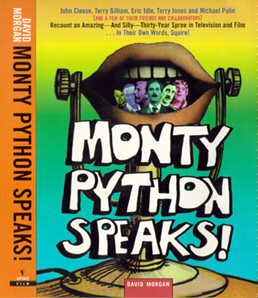

Monty Python Speaks!

David Morgan (1999)

JONES: Originally when we'd been writing for The Frost Report and for Marty Feldman, Mike and I would go and read them through, they'd all laugh, the sketch would get in, and then you see the sketch on the air and they fucking changed it all! We'd get furious. There was one sketch Marty did about a gnome going into a mortgage office to try to raise a mortgage. And he comes in and sits down and talks very sensibly about collateral and everything, and eventually the mortgage guy says, "Well, what's the property?" And he says, "Oh, it's the magic oak tree in Dingly Dell." And the thing went back and forth like that. Everybody laughed when we did it, and when we saw it finally come out on TV, Marty comes in, sits cross-legged on the desk, and starts telling a string of one-line gnome jokes. This wasn't what the joke was at all.

What happens is that people (especially someone like Marty) would start rehearsing it, and of course after you've been rehearsing it a few times people don't laugh anymore. And so Marty being the kind of character he was, he'd throw in a few jokes, and everybody would laugh again. And so that's how things would accumulate. It was things like that that made us want to perform our own stuff. We sort of felt if it worked, you wanted to leave it as it was. (8-9)

CLEESE: And we got to know Peter Sellers. Graham and I wrote two or three screenplays for Sellers, the only one of which that got made was The Magic Christian. We came in on about draft nine of that, did I think a good draft on which they raised the money, and then Terry Southern came back and rewrote it again, and—we thought—made it worse. (17)

BARRY TOOK [Producer]: I had seen Barry Humphries, the Australian, in a one-man show and thought he would make good material for television, and I had this idea of putting this Cleese/Chapman/Palin/Jones together. So I arrive at the BBC and they said, "'Well, Barry Humphries was a female impersonator." I said, "He's not, he's a very broad, interesting comedian, he does all kinds of things, and Edna Everage was just one of his jokes" - it came to overwhelm him in the end, but I mean in those days he had several characters. And they said, "Oh, this Palin and Jones, all that is much too expensive," I said, "You must do it, you've got to. Why the hell have you employed me? You said come in, bring us new ideas, I bring you new ideas, you say: We can't do it. Too expensive."

I thought, you can't fiddle about with these guys, you've got to go for the throat, you've got to say ''You've got to do this!" So my boss at the time, an eccentric man by the name of Michael Mills, said, "You're like bloody Barry Von Richthofen and his Flying Circus. You're so bloody arrogant—Took asks you a question, halfway through you realize he's giving you an order."

So it was known internally as Baron Von Took's Flying Circus. It was then reduced to The Flying Circus and subsequently The Circus. All the internal memos said "The Circus": i.e., "Would you please engage the following people at these prices dah dah dah." I have a copy of the memo somewhere which predates anybody else's claim to have invented the name, it's something I'm fairly jealous about—I mean, I don't give a damn, but I did invent it.

When they wrote their first script, it was called Owl Stretching Time or Whither Canada? and Michael Mills said, "I don't give a damn what it's called, it's called The Circus in all the memos—make them call it 'something Flying Circus.'" (25)

IDLE: It wasn't like U.S. TV at all! We didn't have to do anything as stupid as selling a concept. There was no executive structure. They just gave us thirteen shows and said, "Get on with it." Executives only spoil things and hold back originality—that is their job. (26)

JONES: So I was thinking quite hard about the shape of the show, and I saw [Spike] Milligan's Q5, and I thought, "Fuck! Milligan's done it!" He did a show [where] one sketch would start and drift off into another sketch, things would drift into one another, he made it so clear that we'd been writing in cliches all this time, where we either did three minute sketches with a beginning, middle, and end, or else we did thirty-second blackouts—one joke with a blackout—so it was still very much the shape of a traditional English revue. Milligan was messing around with this and doing something totally different. (30)

IDLE: We were young, and doing a show we would be in charge of for the first time. There were no executives. This freedom allowed us to experiment without having to say what we were trying to do—indeed, we didn't have a clue what we were trying to do except please ourselves. This was the leitmotiv: If it made us laugh, it was in; if it didn't, we sold it to other shows. (37)

[Interviewer:] Was there EVER any consideration given during the writing process to how an audience would respond to the material?

IDLE: None whatsoever. (49)

CLEESE: And the funny thing is I don't remember being cross about it; I think I just accepted that writing with Graham I was going to have to do eighty percent of the work and sometimes more. And it always slightly annoyed me when people used to come up to me on Fawlty Towers and say, "Well, how much did Connie Booth actually write?" And I wanted to say to them, "Certainly a lot more than Graham ever wrote." That used to annoy me, the assumption that because, Graham was a man he was obviously making a bigger contribution than Connie as a woman. (83-4)

[David] SHERLOCK [Graham Chapman's companion]: My mother was terrified of him. She said, "He just sits there smoking his pipe not saying much and I know he's taking it all in, every word! I know it's all going to come out on the television." So that's your average sort of middle-class attitude to what Graham was like. (86)

GILLIAM: He was probably the only one who was really living at the edge in some strange way. We just played at it, we just wrote it; he lived the stuff. (91)

IDLE: Gilliam is one of the most manipulative bastards in that group of utterly manipulative bastards. Michael is a selfish bastard, Cleese a control freak, Jonesy is shagged out and now forgets everything, and Graham as you know is still dead. I am the only real nice one! (107)

IDLE: When we got to the States, we were amazed to find they assumed we wrote it out of our minds on drugs—as if anyone could successfully write stoned. (See Saturday Night Live and Hunter S. Thompson.) When you're stoned it's hard to find the keys to the typewriter. Actually we always worked office hours: Nine to five with a break for lunch. Even in the West Indies!! (112)

CLEESE: I do remember an extraordinary experience: the first time we showed And Now for Something Different [sic], there was hilarious laughter up to fifty minutes, then the audience went quiet for twenty, twenty-five minutes, and then they came up again and finished very well. So we took all that middle material, put it at the beginning, and it all worked beautifully up to about fifty minutes, and then [the] audience got quiet! We discovered that whatever order we put the material in, at about fifty minutes they stopped laughing. And in order to get people to go with you past the fifty-minute mark they have to want to know what's going to happen next. In other words, you have to have characters that they care about and a story they can enjoy and believe in. There's a huge learning curve.

JONES: There was actually an instance where I can remember learning something—and that was when we had the "Dirty Fork" sketch, the waiter comes in and commits suicide and everything. We'd done it on TV and it had been really funny, and we redid it—same sketch, same actors—and we showed it at some Odeon somewhere, and nobody laughed. I thought it was really weird, we'd seen people laugh before and it doesn't get a titter, and the only thing I could see was that Ian had put a muzak track over it, sort of posh restaurant muzak, and I thought maybe that's just filling in all the gaps and just obliterating the film. We took the muzak off and then, when we showed it, people laughed at the sketch again. (120-1)

PALIN: We were interested in the narrative for the films, because we took a conscious decision that films can't just be sketches—there's got to be some story, otherwise people would get bored stiff of just sketches. Certainly after fifty minutes you start to lose them; you've got to have characters that go through. That's a very conscious decision, which is why the Knights of the Round Table was something we thought to be an excellent vehicle. (132-3)

[Interviewer:] Was there interest on the part of Time-Life to sell it here?

[Nancy] LEWIS [Monty Python personal manager]: No, none whatsoever. They said, "Oh, its humor is too English, it's never going to work in America." I had the most discouraging meetings with them—would just come out pulling your hair out. And in those days it did cost a lot to convert from PAL to NTSC standard. It was an expensive procedure and they were not willing—at all—to put money in. (183)

GILLIAM: I had this theory about starting a new series and doing the dullest, most awful shows ever written—boring, not funny, just bad. And the first one goes out, "What's happened to Python?" And you need to run about two or three before people would all stop watching them. You run show after show, and, "Oh, fuck, it's awful!" So by the time there's only maybe ten people left in England who are watching, you then do the best show you've ever done. And they run and tell their friends, and everybody won't believe it! I thought that's what we should be doing: you just lower the expectations so low then you suddenly build them up again. It would require a bit of self-sacrifice! But nobody else went along with that. (199-200)

GOLDSTONE [Executive producer]: The Life of Brian budget—which we maintained—worked because we found this set in Tunisia built for Jesus of Nazareth that was still standing, which we then added on to and elaborated on, and in fact used some of their costumes from a Rome costume house. We were really able to give it a look and a scale without having to spend the kind of money it might have cost. But in those situations, they all rose to the occasion. (233)

PALIN: So one had a character who is exercising power, that's what Pilate is doing. . . .

I suppose it's the sort of paper-thin division between being powerful or being ridiculous. Ceausescu, for instance, was this amazingly powerful man in palaces; overnight, he's suddenly just a frightened man who ends up lying on a yard with a bullet through him. (236)

[Julian] DOYLE [film production]: So I had Eric come to me, and he said, "Don't cut the two-shot, it's brilliant, the close ups don't work." And the same with Graham, he came to me: "Don't cut the two-shot! The two-shot works brilliantly."

This is a thing: comedians will tell you two-shots work, because you get the timing right. Somebody can cut in closeups and ruin somebody's performance by changing their pauses, and that's why I think comedians are [keen] about the two-shot—at least nobody'll ruin it.

I'd done a rough cut of Brian. When we ran the film back in London, they said, "Oh, it's working great except the haggling doesn't work." And Eric was, of course, "Well, we'll have to cut out the haggling." And I said, "Let me have a go at it."

What it was, the haggling was too slow in the two-shot. It works fine when you play it on its own, [but] when you put it in the film, where Brian's being chased by Romans, the performances are too slow. I can speed them up if I go to the closeups and put shots of the Romans getting closer; there's more panic on him. I cut the two-shot with closeups and stuck it in the film. Cleese came around and I ran it: "Well, that seems to work." (246-7)

CLEESE: One of the themes in the film is, "Do make up your own mind about things and don't do what people tell you." And I find it slightly funny that there are now religious organizations saying, "Do not go and see this film that tells you not to do what you are told." (249)

IDLE: The film has appealed to many seriously religious people, including the Dalai Lama and some Jesuits. It [also] plays better in Catholic countries—go figure! But it was wonderful—anger is the hallmark of the closed mind, and we certainly flushed out some raving bigots, and that was part of the joy of it. (249)

IDLE: Like everyone else, I prefer my solo work, because it is mine. You cannot take credit for Python because it is group effort. I like my play, my books, my songs, the Rutles, so much stuff. Python was just a part of my life; it isn't my fault people won't let it go! I have learned you cannot run away from it, you cannot hide from it, and to be polite at all times, but it ain't me, mate. Perhaps having a Beatle for a pal helped me somewhat come to terms with it all. (313)

CLEESE: Sometimes I switch on the BBC and find old Python shows on by accident. I watch them and some of the material, two or three things in every show, seem to be so utterly hopeless that I have no idea—and it's not just that they're not funny, but I don't know how we could have ever thought they might have been. All I know is that we were playing games with convention which no one had ever done before, and it was very startling the first time you do it. But once people get used to a convention being broken it's not startling at all, and then there's nothing left. (314)

|