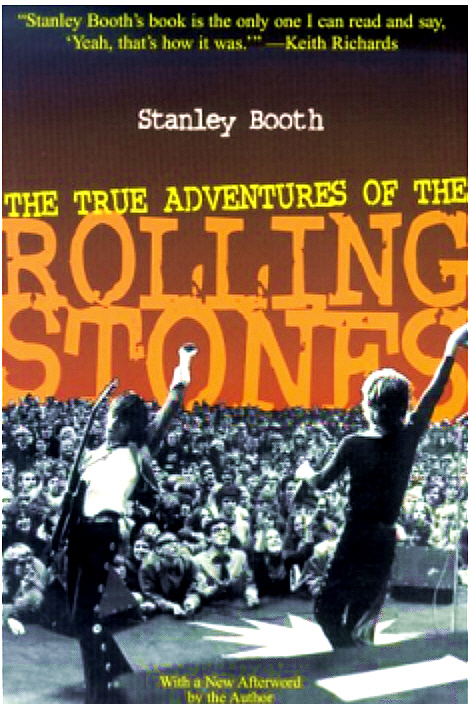

True Adventures of the Rolling Stones

Stanley Booth (1984; rpt. 2000)

Many people encouraged the writing of this book, and a few tried to stop it, making it inevitable.

“Tennis, anyone?” he asked in a voice it would hurt to shave with.

Jo sat in a swing and swung slowly back and forth. It was, as I would learn, typical of the Stones’ manner of doing business that I didn’t know exactly what Jo did for them, and neither did she, and neither did they.

The next thing I knew, Jagger was sitting beside me, asking, “What about this book?” “What about it?” I looked around the room. Steckler and a few other people were there, Jo sitting on the floor with a Polaroid camera, taking a picture of Mick and me. “Those books are never any good,” Mick said. “That’s true,” I said, assuming that he meant books like My Story by Zsa Zsa Gabor, as told to Gerold Frank. “But I’m not going to write one of those books.”

I had taken flights at family rates to research the stories I wrote so slowly that no one could imagine how desperate I was for the money.

[S]omeone—Phil Kaufman—passed around a handful of joints. Kaufman, from Los Angeles, a dwarfy German type with a yellow mustache, hung out with Gram and had been hired to help take care of the Stones while they were in town. He had done time on a dope charge at Terminal Island Correctional Institute, San Pedro, California, with someone named Charlie Manson. The rest of us had not heard of Manson yet, although we soon would, but it would be several years—four—before Kaufman made the news by stealing Gram’s dead body from a baggage ramp at the L.A. airport and burning it in the Mojave Desert. (The subject of funeral arrangements had come up during a conversation between Gram and Phil some months before the night—in September 1973—when Gram overdosed on morphine and alcohol.)

I walked on to a side street, found a phone kiosk, and from its picture in the yellow pages chose the Majestic Hotel on Park Place. It looked like the hotel where W. C. Fields would stay when he was in town.

Cheltenham was designed to be a nice place, and it is a nice place, up to the point where they decide you are not so nice. Some of Cheltenham’s nicest people had not spoken to Brian Jones’ mother and father in years, while others stopped speaking to them only when Brian was buried in consecrated ground, his final outrage. You can listen close and hear the clippers clipping the hedges of Cheltenham.

Her hair was as yellow as Brian’s, a shade that appeared to age well if given the chance.

But this generation, like every other, contained mostly dull-normal people who needed others to live their lives for them. Luckily there are always a few people who can and do live other people’s lives for them. They are the stars of the time, and at this time no public figure was so loved and hated as Mick Jagger, what a name, a name to open sardine tins with.

The first night I spent at Keith’s house, Anita tossed a blanket beside me on the cushion where I was lying. “You don’t need sheets, do you,” she asked. “No, I’ll be fine,” I said. “Mick has to have sheets,” she said. “Put it in the book.”

When I started going to school, just after the war, they taught you the basics, but mainly it was indoctrination in the way schools were run, who’s to say yes to who and how to find your place in class. It’s what you’ve let yourself in for for the next ten years.

“When I was twelve years old,” Mick said, “I worked on an American army base near Dartford, giving other kids physical instruction—because I was good at it. I had to learn their games, so I learned football and baseball, all the American games. There was a black cat there named José, a cook, who played R&B records for me. That was the first time I heard black music. In fact that was my first encounter with American thought. They buried a flag, a piece of cloth, with full military honors. I thought it was ridiculous, and said so. They said, ‘How would you feel if we said something about the Queen?’ I said, ‘I wouldn’t mind, you wouldn’t be talking about me. She might mind, but I wouldn’t.’ ”

I did not say, Where the hell is Keith? but airily remarked, “Insane business, people running about.” It was the first sentence I could remember saying to Mick Taylor. He smiled simply and said, “I don’t mind the business part as long as I don’t have to do it.” Then I said, “Where the hell is Keith?”

Still, I had the letter, the letter was signed, it was in my notebook, my note-book was in my hand. We were rolling in a limousine past expensive houses on streets named after birds.

Later, when Chuck Berry was out of prison and Mick and Keith were Rolling Stones, they met him, and unlike many of their musical idols, he snubbed them repeatedly, so that they respected him all the more and were trying to hire him for the present tour.

In Manchester, at the Palace, a girl fell fifteen feet from the upper circle of seats into the stalls. The fall went almost unnoticed as 150 screaming girls stormed the stage when Mick sang “Pain in My Heart.” The girl ran away from attendants attempting to take her to an ambulance and was later seen outside the stage door, still screaming, “Mick, Mick.”

Then “eight or nine youths and girls got out of the car.” Mr. Keeley, “sensing trouble,” told the driver of the car, Mick Jagger, to get them off the forecourt. Jagger pushed him aside and said, “We’ll piss anywhere, man.” This phrase was taken up by the others, who repeated it in “a gentle chant.” One danced to the phrase. Then Wyman went to the road and urinated against a garage. Mick Jagger and Brian Jones followed suit farther down the road. According to Mr. Keeley, “Some people did not seem offended. They even went up and asked for autographs.” One customer, however, told the Stones their behavior was “disgusting.” At this the Stones “started shouting and screaming.” The incident ended with the Daimler driving away, its occupants making “a well-known gesture with two fingers.” Mr. Keeley took down the license number.

“Mick was very edgy, because he was having a lot of arguments with his family. I remember his mother ringing me up one night and saying ‘We’ve always felt that Mick was the least talented member of the family, do you really think he has any career in music?’ I told her that I didn’t think he could possibly fail. She didn’t believe me—she didn’t see how I could make a statement of that sort. I don’t suppose she can to this day. Don’t suppose she’ll ever understand why he is what he is."

We were locked up in the studio not because of the dope but because the Stones, lacking work permits, were not supposed to use American recording studios. What they were doing was illegal, and they were enjoying it very much.

With him in Hush Puppies and a yellow T-shirt, looking, though only in his thirties, old and grey and sort of like Jack Ruby with cancer, was the legendary Allen Klein, who I realized had failed to squash my plans for a book like a bug under his Hush Puppies only because, so far, he hadn’t got around to it.

I wondered what the hell I was doing with these mad English owl-hoots, and what were they doing that they needed Allen Klein, who scared Phil Spector, a man with so many bodyguards and fences and so much bullet-proof glass that he ridiculed the Stones for getting arrested; even Spector seemed afraid of this pudgy glum-faced accountant in his bulging yellow T-shirt.

I did not know yet how good or evil the Stones were, but of Klein I was simply afraid, because even though I had a letter from the Stones, a magic piece of paper, there was still the tour, this gauntlet I had to run, and a man like Klein could, I sensed, stop me any time he wanted to take the trouble. But when I was twelve, standing in the dark outside my grandfather’s house, frightened nearly to death, I was still, in some part of my mind that is a gift from my father who got it from his father who got it from God knows where, calm and ready, I think, to do what had to be done.

So I stayed calm and steady in my terror, sensing the craziness of the Stones, of mad Keith, and knowing that what the Stones had already done had killed one of them.

Everybody—the people at work, my friends, my parents, my wife—said I should keep my job and not go with the Stones. Later, when we were a success, they said, ‘See, I knew you could make it.’”

Glyn Johns: “I can remember taking them to I.B.C. for the first session and being frightened of introducing them to George Clouston, the guy who owned the studio. I see photographs of them then and they look so tame and harmless, I can’t associate it with the effect they had on people. It was just their appearance, their clothes, their hair, their whole attitude was immediately obvious to you as soon as you saw them playing. It was just a complete pppprt to society and everybody and anything.”

Monck had again fallen asleep sitting up. He was the only person I had ever seen who could make falling asleep pretentious.

I.B.C. had done nothing with the tapes. “They had no outlet,” Keith said. “They didn’t know how to cut them or get them onto discs, and they couldn’t get any record company interested in them. This recording contract, although it’s nothing, is still a binding contract, and Brian pulls another one of his fantastic get-out schemes. Before this cat Clouston can hear that we’re signing with Decca, Brian goes to see him with a hundred quid that Andrew and Eric have given him, and he says, ‘Look, we’re not interested, we’re breaking up as a band, we’re not going to play anymore, we’ve given up, but in case we get something together in the future, we don’t want to be tied down by this contract, so can we buy ourselves out of it for a hundred pounds?’ And after hearing this story, which he obviously believes, this old Scrooge takes the hundred quid. The next day he hears that we’ve got a contract with Decca, we’re gonna be making our first single, London’s answer to the Beatles, folks.”

Then Wyman had an idea—for an invention, an instrument that could be attached to a guitar and would light up when a string was in tune. Jagger and Keith insisted it was impossible. Charlie said it was possible and so did I. Keith was down on the whole idea. “Use your ears,” he said. “Yeah,” said Jagger. “That’s what you’ve got your god-given talent for.” “Actually I was thinkin’ of it for you, man,” Bill said to Keith. “I don’t have any trouble stayin’ in tune, you’re the one.”

I took the call in the kitchen. We had a short version of the same phone conversation we had had every few months for years, a ritual of private jokes to let each other know that we were still ourselves, nothing had changed.

When the Newsweek talk ended and the reporter left, we all decided to have lunch together on the Strip. Charlie and I went inside for a minute and came back to see the other Stones driving away in a turquoise Continental. “Really, they are the rudest people,” Charlie said.

What it comes down to, Gram said, is a man and a woman. I’ve got a little baby girl, beautiful, she’s with her mother—I passed him the end of the joint and he said, What we got to have in this world is more love or more slack.

I remembered seeing, back at the Oriole house, an interview in an old issue of a music magazine with Jim Morrison asking the interviewer, “You were in Chicago—what was it like?” and the interviewer saying, “It was like a Rolling Stones concert.”

A little later, Shirley joined us. We were discussing the frantic business machinations of the ones she called “the bought people,” and Shirley said, “And it’s just a tour, after all, just a group of people going around getting up on stages and playing music for kids to dance.” “If you don’t put that in your book, I’ll kill you,” Charlie said.

The Stones shared billing on the show with such acts as the Searchers, Brian Poole and the Tremeloes, and Craig Douglas, who had a weekly television program where he plugged his own records, some of which became hits. Douglas, who before going into show business had been a milkman, was very rude to the Stones, refusing to speak to “those scum.” They left outside his dressing room door a milk bottle with a note in it saying “Two pints, please.”

The next night they played at Eel Pie Island, and on the next at a place they’d never been, the Cellar Club in Kingston, where the audience was friendly, but once the show was over and the people had left, the promoter told the Stones, “You’ve got five minutes to get out.” They thought he was joking and paid no attention, but he went into his office and came back wearing one boxing glove, raging: “I said, Tack up!’ ” As they drove away the man came outside brandishing a shotgun.

If the Stones were astonished to be playing with Bo Diddley, how must Bo Diddley (born Ellas McDaniel near Magnolia, Mississippi) have felt, seeing a blond English cherub with a bruised and swollen eye, playing guitar just like Elmore James, who had learned from Robert Johnson, who had learned at the crossroads from the Devil himself.

“Brian Jones, the leader,” answers the question, “How did you come to play R&B?” by saying, “It’s really a matter for a sociologist, a psychiatrist, or something. . . . If you ask some people why they go for R&B you get pretentious answers. They say that in R&B they find ‘an honesty of expression, a sincerity of feeling,’ and so on, for me it’s merely the sound. . . . I mean, I like all sorts of sounds, like church-bells for instance, I always stop and listen to church-bells. It doesn’t express damn-all to me, really . . . but I like the sound. . . .”

[T]he night after that, they played the Cavern, the Liverpool basement nightclub where the Beatles used to play. “It was like playing a Turkish bath, all stone, had a terrible sound,” Keith said. “You can’t imagine what a myth was built around it.”

A newspaper had quoted Mick as saying, “Can you imagine a British-composed R&B number—it just wouldn’t make it.” But Andrew, with plans to publish Jagger/Richards songs, was according to Keith “very much into hustling Mick and me to write songs, which we’d never have thought of doing. Brian wrote one once. . . .”

“When, finally, the spotlight was switched off them,” the accompanying story said of the Stones, “there was a chase for the dressing room. Who would win, the group or the girls? Four of the group made it but the drummer was pulled to the ground and lost his shirt and half his vest. Girl fans fell on top of him. . . . Eventually the bouncers employed to keep patrons in order managed to free him and rush him to the dressing room, where his own girlfriend looked after him.” His own girlfriend was Shirley Ann Shepherd, an art teacher, his wife-to-be. But Charlie was for the moment inconsolable, walking around holding a few shreds of cloth, muttering, “They tore me shirt.”

At Guildford the Stones played a rhythm & blues concert with the Graham Bond Quartet, the singer Georgie Fame, and a band called the Yardbirds, who before they were a band would come to the Richmond Crawdaddy Club each time the Stones played. Each of the future Yardbirds would watch the Stone who played his instrument, ask him questions, and by the time the Stones stopped playing at Richmond the Yardbirds knew their whole act.

Keith, talking to a hungry-looking interviewer from an “underground” newspaper, said as I passed, going to sit on the couch, that the Stones’ contracts stated that no uniformed police were to be allowed inside the arenas where the Stones would play: “Uniforms are a definite bad scene.”

I made a note myself, of something I heard Ronnie say on the telephone this afternoon: “He did the worst thing you can do to anybody. Sure you know what that is. He turned him in to the Internal Revenue.”

But he did have horn-rim glasses and a suit that looked as if it had become shiny from lying on the couches of expensively upholstered psychiatrists.

Keith, who had gone to see Bo Diddley last night and got to bed at six A.M., said, “Sam, bring me a vodka.” “But you said you didn’t want nothing till you got on the plane,” Sam said. As if he were speaking to himself Keith said, “Must get used to my—unpredictability.”

I put on a pair also and dialed the same channel, to hear Otis Redding. “Nice,” I said, but Mick said, “Bad karma for a plane ride.”

I began to see what the tour was about. When we are young, innocent, and ignorant, and we look and smell good, all that is required is a little rhythm—what could be more revolutionary, more troublemaking, than bringing rhythm to the scent of the classroom?

Grateful Dead factotum Rock Scully is here, grimy, saying, “Well, we’ve got a lot of work to do,” sounding like someone who would go right on saying that forever.

Then B.B. stopped talking, was quiet for a moment, played eight searing bars of blues, and sang, “When I read your letter this morning, that was in your place in bed.” The crowd, white city people, hooted and hollered, and for the moment even the cops seemed to stop harassing bystanders.

Halfway down the hall Pete Bennett borrowed my pen to write the name and address of a girl he had trapped there. “I want her face for an album. She’s got an album face.”

I kept writing, hoping that I’d be left alone, which writers spend their lives hoping, but it never happens.

The first week of January 1964 the Stones opened a tour of England, billed second to a trio of black American girl singers called the Ronettes, who quickly saw that to follow the Rolling Stones onstage was to commit professional suicide. After that the Stones always played last and got top billing.

Other fans were now breaking out the Stones’ dressing room windows, stripping the van of its lights, mirrors, even the rubber window mounts; popularity had become hysteria. Stu said, “It wasn’t pleasant to see what the music did to people.” It was the looks on their faces that had changed, that you did not like to see, the straining, screaming faces of young English girls, sweating and squealing like pigs, not loose and happy like raving together at the Crawdaddy but reaching out for something separate from themselves, not the music but the musicians, to touch them, tear them asunder to find out what manner of magical beings have let loose this madness.

After taking their leave of the police, the Stones went back to Chess and recorded twelve more songs. Muddy Waters was there and helped them carry in their equipment. The graciousness of Muddy, from whose song “Rollin’ Stone” Brian had taken their name, was touching.

The Stones were recording Chuck Berry’s “Around and Around” when Berry walked in. A week before they left England, Mick and Charlie happened to confront Berry, after he had snubbed them backstage at Finsbury Park. They were in a hotel elevator: the elevator stopped at a floor, the door opened, there stood Berry, who stepped aboard, saw Mick and Charlie, turned his back, when the door opened again he walked out, wouldn’t speak. But this time he was trapped. “Swing on, gentlemen, you are sounding most well if I may say so,” he said, sounding like Duke Ellington at his most unguent.

It was like being gypsies. I remembered the gypsy boy buried by the roadside on the way down to Wyman’s house from London. He had been hanged for a crime the gypsies say he did not commit, and each year on the date of the hanging, the morning finds fresh flowers on the grave, the grave now more than two hundred years old, but the gypsies’ memory is older than night.

Wyman’s small, light bass (a Fender Mustang) creating a mountainous sound with great reverberating overtones. How he did it was a mystery. That Wyman was a Rolling Stone was a mystery, but there he was, a little old man, and just listen. He never danced, never even moved. “Once in a while I sweat a little bit under me arms,” he said.

The Be-In, a mass gathering, had taken place in the park with no unpleasantness. The Hell’s Angels, who had attended the Be-In, had acted as security at some Grateful Dead concerts, and it was natural (not to say organic) to have the Angels help you do your thing, or so it seemed to Rock Scully. He was saying, sitting on a couch in that oblong room where our destinies were being formed, though we were too tired to give much of a shit, “The Angels are really some righteous dudes. They carry themselves with honor and dignity.” He was so wide-eyed and open about it, it seemed really convincing. Nobody was even particularly paying attention, but I noticed the way he used the words honor and dignity, these high-flown words here but you know what I mean.

Keith was furious, and when Keith was furious, everybody else had better be at least indignant.

Jagger came in, still in his black stage garb, opened a bottle of champagne, and sat down on the floor. “I’ve been watchin’ Tina,” he said, “and she is so good, she’s fucking fantastic, the way she is onstage. I mean, she’s so cocky. I used to be cocky, but I ain’t anymore.” Ike and Tina burst in, and Mick got up to greet them. “Tina, you were fantastic.” They talked briefly, Ike and Tina left, then Tina looked back in to say to Mick, “Watch it with the Ikettes. Last time, we got ready to go, and no Ikettes.” “Whaddya want me to do?” “Do what you want, but be cool.” “I haven’t done anything yet,” Mick said, sounding like a little boy.

None of the shows had been without problems, and yet the screams got screamed, the sweat sweated, the shows done. That might be the whole point, the only victory might be in simple survival. Or so it might seem if Mick didn’t keep leaning out over the stage each night, singing, as if it were a Sunday School song, “I’m free—to do what I like, justa any old time—and I ain’t gonna give you no bullshit—ain’t gonna give you no lies—we’re free—you know we all free.” It never sounded true. If it were true, true just once, if ever you had the feeling that you could let go, jump up, sing “Honky Tonk Women,” dance, do what you like, without the fear of a cop’s club or Klein’s mop-handle against your skull—that would be a victory.

As “Street Fighting Man” started, Mick said, perhaps sensing the militarism of the town, “Sometime we may have to get up against the wall.” Mick was making a V-sign with each hand as Keith ripped the opening chords: “Everywhere I hear the sound of marchin’ chargin’ feet, boys.” I had left my seat and was by the stage, a helmeted cop beside me putting his fingers over his ears, grimacing.

Shirley was saying, “You may put in your book that Mrs. Watts was once again brutally manhandled by a security guard.” She had been sitting with Astrid, and as they were going backstage when the aisles started to fill up, a guard knocked her to the ground, then went to get a helmeted cop to throw her out. The cop recognized her and the guard apologized, saying, “I didn’t know who you were.” “That’s no way to treat any girl,” Shirley told him. I was properly indignant over the abuse to Shirley’s person, but I couldn’t help thinking that any red-blooded cop might make such a mistake. Shirley loved rock and roll music and got excited and when she did she might have been any pretty teenager, and that was enough to make a cop want to hit her, to strike out at her pretty pleasure which had nothing to do with him or anything like him.

De old bee make de honeycomb / De young bee make de honey / De Good Lord make all de pretty gals / An’ Sears Roebuck make de money — FURRY LEWIS

Next, New York City, the Astor, then to Providence and a cinema where no live act had ever played. The management had covered the orchestra pit with thin plywood, and when the Stones started playing, girls ran down the aisles, jumped onto the plywood and disappeared into the pit.

In a corner of the room a television set was giving the news, sending into the room horrors of oriental wars, zodiac killers. Charlie, on one of the couches, was watching, smiling his pleasant amazed smile.

I had spoken to Jo about the badness of “I’m Free,” and on the drive to the airport, Glyn Johns, on the tour to plan a live album, was complaining about it: “Mick’s recently come across the word messianic, and he’s quite fascinated with it. It’s in this new song, ‘Monkey Man,’ you know. He can be as messianic as he wants, but as far as I’m concerned, when he says we’re all free, he’s talkin’ out his arse.”

Through a slit in the back curtain a cowpoke wearing a straw hat poked his sunburned head, looking at the crowd with wonder, as if he were sitting on a church steeple watching a cattle stampede.

Up a few stairs, black curtains hid an alcove under a sign saying Adults Only Sleeping Beauty Ball Toss. I couldn’t stand the suspense and stepped past the curtains to find a young man behind a counter where baseballs were stacked inside billiard racks. About fifteen feet behind him was a green metal disc a few inches wide. Farther back, displayed on a couch under a rose-colored light, behind a gauze curtain, was a girl wearing tiny rose-colored panties and a chiffon shawl. “What happens?” “Try and see,” she said, so I bought three balls for a dollar and hit the disc with the second. Music started and up she rose, a big strong girl who in quieter times might have gone to bed at sundown and got up in the cold morning to jerk warm milk from cows, but who was in Las Vegas twisting her pelvis for a stranger who hit a target with a baseball. “How long have you been doing this?” “Too long,” she said, twisting.

The next day they drove three hours to the Treasure Island Gardens in London, Ontario, where the police, alarmed by the spectacle of three thousand people having a good time, stopped the show during the fifth song, inspiring the audience, many of whom had driven all the way from Detroit, to riot.

Freddy “Boom-Boom” Cannon, who had said, after his recording of “Tallahassee Lassie” sold over a million copies, that he had never been to Tallahassee but now thought he might like to go.

Back to the motel, nothing to do in Clearwater but sit by the pool. Charlie wished he were home with Shirley. Bill and Brian were with two girls they had carried into the South like prospectors taking extra canteens into the desert.

Before they could leave, the car was covered with bodies, the roof collapsing, the Stones holding it up as the driver tried to inch the big car forward through the crowd. Finally cops with clubs climbed on the car, beating the kids back, hurting many of them. Once past the crowd, the Stones raced to a waiting helicopter. The crowd like locusts covered the car again and the Stones watched the car being torn apart as they ascended.

Andrew told reporters that the first of the Decca-financed Stones movies would be made within the next six months, but that it was “too early to say” what the movies would be like. Mick snarled at one reporter, “We’re not gonna make Beatles movies. We’re not comedians.”

Most of the Stones’ fans in the United States at this time were quite young girls who thought that anything English was exotic and adorable, but a writer at the Hilton press conference said the Stones looked “like five unfolding switchblades,” adding, “I left with the terrible feeling that if Kropotkin were alive in the 1960s he would almost certainly have had a press agent.”

On October 29 the Stones flew to Montreal, handing over the passports in a bundle so the customs officers wouldn’t notice that Keith’s was missing.

The audience consisted almost entirely of pubescent girls, some with Mom and Dad, all white, shrieking at the tops of their piping little voices. The Stones’ show was not a concert but a ritual; their songs, compared in content or manner of performance with the material of other popular musicians, were acts of violence, brief and incandescent. Mick threw a tambourine into the audience, and hundreds dived for it. Years later I would get the Stones’ autographs for the girl who caught the tambourine, its sharp-edged cymbals slicing her hands so badly that she had to be taken to a hospital emergency room and stitched together.

. . . Phoenix, where the Stones stayed in Scottsdale and went riding on the desert.

"Charles Bolden, a musician, of 2302 First Street, hammered his mother-in-law, Mrs. Ida Beach, in their house yesterday afternoon. It seems that Bolden has been confined to his bed since Saturday, and was violent. Yesterday he believed that his mother-in-law was drugging him, and getting out of bed, he hit the woman on the head with a pitcher and cut her scalp. The wound was not serious. Bolden was placed under a close watch, as the physicians stated that he was liable to harm someone in his condition." —New Orleans Daily Picayune, 1906

Dickinson drove slowly on, explaining things to me, for which I kept him around. “The Stones are trying to tour without a big agency booking them because they’ve been fucked by agencies,” he said. “They didn’t trust house PAs or equipment rental agencies, and they felt they should give audiences a record-quality sound, so they got their own PA and a mixing board. They’re controlling their own tour. They haven’t booked the typical cow palaces—some, enough to make money—but they’re in the revolution, they’ll play places the Beatles wouldn’t. They wind up hiring their friends who are actually incompetent. My God, they were late. Only acts of God excuse musicians.” I made a note to ask about that.

March 3 the Stones reached Los Angeles, where they stayed four days, long enough to record the Jagger/Richards song, “Paint It, Black.” It was to be their next single. The comma was Andrew’s idea.

At the end of March and into April, the Stones toured Europe, including Amsterdam, Brussels, Paris—where Brigitte Bardot came to their hotel to meet them, a rather embarrassing scene since only Mick spoke French, and her beauty made him speechless.

Years later Charlie would recall how Brian “sat for hours learning to play sitar, put it on Paint It, Black’ and never played it again.”

Plans for the Stones’ film, supposed to have started in April, had changed again. The film was now to be taken from a novel called Only Lovers Left Alive, by Dave Wallis, about England taken over by teenagers after a nuclear attack. Mick told Melody Maker, “I can’t see, for instance, Ringo with a gun in his hand and being nasty in a movie and going to kill somebody. It just wouldn’t happen. But I don’t think you’d think it was very peculiar if you saw Brian do it.”

Fans broke through the police cordon, and cops threw tear gas that the wind blew away from the crowd and back toward the stage. The Stones beat it for their two limousines, but the fans caught up with the cars, which were nearly torn apart. As the cars took off, one girl, clinging to the rear bumper, lost two fingers. “Brian, Brian,” she screamed, not knowing that her life—or at least her hand—had been changed forever.

On the rear wall, a painted sign said HOME OF THE INTERNATIONAL LIVESTOCK EXPOSITION. In this dusty old rust-colored barn the obligatory U.S. flag was huge, hanging in the dead center of the room. If it fell rows of customers would smother.

Keith and I were in his suite, talking as he packed. He dropped a pack of cigarettes, bent to pick them up, and dropped them again. “It’s that time of night when you drop things and can’t pick them up,” he said.

The driver of one of the limousines that took us to the airport was the man who drove the judge of the Chicago Eight trial to court every morning. “What does the judge say about Abbie?” I asked. “He hates him. Says he’s going to jail.” On the plane, I reminded Mick that at the Woodstock festival Abbie had tried to address the crowd and had been hit on the head with a guitar by Pete Townshend of the Who. “I don’t blame Townshend, I’d probably have done the same thing,” Mick said.

Charlie joined me and asked, “Is he good, that Abbie guy? Is he a good guy?” “Well,” I said, “it depends—” “I mean, he doesn’t carry himself like somebody you’d respect. He’s like a clown.” “Maybe in politics these days the clowns are the most respectable people.” “Sad, isn’t it?” Charlie said.

The name she was using now, so pretentious and phony a stripper couldn’t have stayed in business with it, nevertheless, combining the French words for alone, love, cat, and night, told you a lot about Cynthia and made her easy to find in the Manhattan directory.

The show was hard and fast without “I’m Free,” but it seemed, in spite of all the action, like an old-fashioned rock and roll show of the fifties, people having a good time within the imposed limits. Ripping up seats expresses frustration, but it doesn’t change much besides the seats.

“Come on in,” Mick said, opening the limousine door. “Too bad you missed last night’s concert, it was good. Here’s a tape.” Mick turned up the volume control of a portable tape recorder he was holding on his lap. “Who made it?” I asked. “A kid. It was confiscated.” “By Schneider?” “Yes,” Mick said. “He’s awful.”

Mick and Ronnie were talking about record companies, how to make the best deal—Ronnie was always discussing deals because that was how he made his living. “Why do you have to deal with them other motherfuckers at all?” Tony asked. “Why mess with record companies and distributors? Why don’t the heads put out their own shit?” “Because it’s too complicated,” Keith said. “There’s too much involved. You’d have to do all the pressing and distribution yourself, have to own a fleet of trucks. That’s the problem. Phil Spector tried it, he cheated and bribed and did everything he could to get started, and that’s cool, but he couldn’t do it, it didn’t work.” He paused for a moment, then said, “Still it must be possible. How do bootleg records get around, how does grass get around, that’s the way it’s got to work—”

At each Rolling Stones concert there were indications that we were fighting for something tender and lovely and free, but what a hell of a world we had to fight, when the land of the free and the home of the brave was sending its sons out to slaughter women and children, and the sons, men my age and younger, were doing it.

Christopher and I wanted to be together, but I wanted to wait until I was making some money. I also thought that if marriage wasn’t good enough for James Joyce or Pablo Picasso, it wasn’t good enough for me. That is, I shared their disregard for the convention that makes love the business of bureaucrats.

The front door was unlocked. Just inside, a search warrant lay on the floor. The air stank with gas. We went through the rooms, opening windows and closing valves. The police had turned all the heating outlets on and left them unlighted in the hope that Charlie would come in and light a cigaret. In their search they had knocked holes in the walls, poured chemicals into all the liquids in the place, broken almost everything that would break.

When Brian came back to the hotel and found himself abandoned, he attempted suicide. Gysin got him a doctor and nursed him back to whatever he had instead of health.

We were interrupted by William Burroughs, who came in and sat down, wearing a hat and overcoat. He was the drunkest man I had seen since I had last seen Furry Lewis. Reduced in Burroughs’ presence as Keith was reduced by Chuck Berry, I found myself telling him about my prized copy of Big Table 1 with its first U.S. printing of parts of Naked Lunch. “Oh, wow,” Burroughs said, seeming to awaken. “That’s a real collectors’ item.” His eyes narrowed. “They are—now—quite valuable collectors’ items—and—y’know—if you want to—I could autograph it, and we would—ah—share—” “Make a little exchange,” Gysin said. “—anything—we could get—on the collectors’ market.” I rested easier then, because I knew I was talking to men who, like Furry Lewis, would burn a guitar for firewood. Burroughs began to grumble about not wanting to be an artist, just wanting to make money; I quoted Shaw to Goldwyn: The difference between us is that you care only about art and I care only about money. “There you go,” Burroughs said. “No one who is an artist gives a shit about being an artist. They want to make a little money and have a little peace. Be an artist, indeed.”

The place was like a gypsy camp: bodyguards all over, waiters carrying trays of food in and empty plates out, an ex-Lawrence Welk child prodigy pianist touting his four older sisters’ rock band (the Hedonists), and Barbara, a pretty girl with brown hair and Bambi eyes. She was a model but she didn’t have that evil model look. Jaymes was going to have her travel around in a bikini and help him demonstrate Laugh-In body paint. “This is a real break for me,” she said.

Jon Jaymes was standing beside the table, hands raised toward the press, looking like a man conducting the antics of a bevy of magpies.

I stopped to talk to Lillian Roxon, who had written a book called The Rock Encyclopedia. An Australian, Lillian was a good-looking blond girl with pale blue eyes, but she had gained forty pounds writing her book—which seemed like a lot to go through for a rock and roll book, how little I knew—and soon she was going to be dead, another dead one.

We went down to the street and there was the bus. In it were the driver and some of Jaymes’ federal narcotics agents and off-duty New York City detectives, big short-haired men in golf jackets and Hush Puppies. They had nice faces with sad wise expressions, sorrowful like very old priests or midwives, as if they had seen all the bloody consequences of man’s folly.

All the Thanksgiving travellers sat silent, Muzak filling the darkness. Slowly the train rolled out to where the sunlight was starting to burn away the mist. Across the aisle a whitehaired man was telling his two grandsons, who looked about nine and twelve, that for years their father worked for Western Union and had a free pass on the railroad, never had to pay. The boys rolled their eyes, bad actors expressing boredom. The grandfather went on talking, trying to get them to look at the scenery, to live life, to see, to care, but the boys ignored him, thinking they would live forever.

The last time I’d seen Wexler, he’d said, “The Stones sent me a tape of this song, ‘Sympathy for the Devil.’ They wanted Aretha to record it. The only artists on Atlantic who could record those lyrics are Sonny Bono and Burl Ives.”

“Wouldn’t hurt to ask.” I made the phone call to Dickinson, and some of us lived through what it caused and one of the best of us, Charlie Freeman, didn’t.

As Stu said, “If Brian Jones, Bill Wyman, Charlie Watts, and myself had never existed on the face of this earth, Mick and Keith would still have had a group that looked and sounded like the Rolling Stones.”

I crossed the street again and there was Gore, blond and tortoise-shelled and schoolboyish. He said his regular speed doctor was out of town, so we walked back over near the Plaza for a visit with one Adolf B. Wolfmann, M.D., D.D.S., D.M.D. He was not quite as bad as Peter Sellers in The Wrong Box, blotting his prescriptions with a kitten, but he gave you the feeling he had a lot to be surreptitious about.

Sam was coming out, more mad-eyed than ever, to the mike: “The greatest rock and roll band in the world, the Rolling Stones.” I kept wishing he would say, “The scaredest rock and roll band,” but he never did, not even later, when there was no doubt about it.

The traditional esthetic of popular songs required that the singer’s life should be made desolate by the departure of his true love, who could make everything all right if only she would return. If such songs as Bob Dylan’s “It Ain’t Me, Babe” and the Stones’ “Stupid Girl” and “Under My Thumb” defied that convention, they were not quite the same thing as songs about rape and murder. “Some of those early albums, like Between the Buttons, were so light” Mick had said one day at the Oriole house while we were listening to an acetate of Let It Bleed. This tour would lighten his approach for good. He would go on singing about death and destruction, but he would cut out the Prince of Darkness business. He was about to have more darkness than he ever wanted.

But as I climbed the stairs, two men I’d never seen before grabbed me and started to throw me off. “Hey! Wait a minute!” I yelled, no time to reason with them. They were shoving me off the side of the stairs, I grabbed their arms, trying not to fall—and Ronnie and a couple of our familiar security men stopped them. “God, you people are rude,” I told the gentlemen who’d been trying to break my neck. “Buddy, this is my livelihood,” one of them explained.

Sam, bent over like a graverobber, slipped onstage to put a Coke on the drum stand where Mick could reach it, sticking his head under Charlie’s crash cymbal, and Charlie, seeing him, hit it harder.

At the sidewalk, as we were getting into the limos, a large black woman came up and said, “I want yawlses autographs.” Nobody paid any attention to her; everybody piled into the cars, and just before the doors closed she said, “I never will buy no mo’ Rollin’ Stones records.”

“I wanted to do the whole tour free,” Mick said, “till I talked to my bank manager. They tell you you’re doing great, you’ve got all this money, until you want to buy something, some chairs or something, and then you discover you don’t—you only give me your funny pay-pah.” He sang the last line.

“Some of them asked me if I wanted to go to a deb ball,” Mick said, “and I told them that there are no real debutantes in America.” “What do you mean, there are no—” Michael said. “There aren’t. There isn’t,” Mick said, “any American aristocracy, so there can’t be any debutantes.” “But there isn’t any anywhere, really,” Michael said. “Of course there is,” Mick said. “There is in England.” “He thinks he’ll be knighted,” I said, “that’s why he says that.” “Doesn’t do you any good to be knighted,” Mick said. “You have to be a baronet at least, that’s the lowest—you’re automatically a sir if you’re a baronet.

“But you really believe in the aristocracy,” Michael said, missing Mick’s irony. “Well, nobody’s about to do anything about that system. We have now a chance, since they gave the vote to eighteen-year-olds, to get three million new voters, make a change, destroy an irrelevant system. But England’s so stagnant, the kids there are just like they’ve always been. Nobody’s interested in doing anything except some people who are already into politics. You can’t get anything together there. This is our only chance in the last fifty years to really change things, and nobody cares—” “Change them to what?” Charlie asked. He and Sam Cutler were sitting nearby. “What are you going to put in place of the system we have now?” “Nothing,” Mick said. “Nothing would be better than a system that’s irrelevant.” “That’s right” Sam said. “We just need to stop the cops, right, from pushing people around. Eventually it comes down to that.”

After spending weeks going from California, the Southwest, to Alabama, Chicago, the Eastern Seaboard, trying night after night to shake another bit of America loose, we sat waiting to fly to the last gig in Florida, helpless in an airplane that wasn’t going anywhere, and began to discuss for the first time the question What Is To Be Done. “The theme that keeps constantly recurring in your thoughts, man,” Charlie told Sam, “is hitting a cop.” “My old man was a red, right,” Sam said, “and I’ve seen what the cops do. I’ve seen them seize the subscription list of the International Times. There comes a time when you have to say, ‘Right, this is it, I’m not moving.’ ” “But everybody in politics is pushing you out into the street,” Charlie said. “I don’t like it.” “Wouldn’t you go into the streets to fight the cops if it came to that?” Sam asked. “No,” Charlie said. “I wouldn’t.” “Charlie’s a true cockney,” Mick said to me, as Sam went on trying to convince Charlie that hitting cops would solve the world’s problems. “A real Londoner. But now he lives in the country and a lot of things I hate about country people I can see in Charlie. He’ll join a preservation society and spend his time writing letters.” “I don’t know about the societies,” I said, “but preservation is what I’d like to see, the preservation of life on the planet, there’s not a stream in my home county that isn’t polluted—” “I don’t know,” Mick said, “maybe the natural thing is for the streams to be polluted, for it to die. Maybe that’s what should happen.” “I hope not,” I said. We broke off talking because Keith came by, somehow showing just by walking past the idleness of our chatter: it’s not what you say that counts.

Feeling a bit faint, I took out an amyl nitrite popper, broke it, inhaled it, passed it to the Maysles brothers, who inhaled without knowing what it was, and I enjoyed watching their surprise as their heads inflated.

Mick looked out one of the portholes. “If one does what he does for God, or the Good,” he said, looking tired and pale, “then I haven’t been able to find anybody doing anything better—certainly anybody in politics—than what I’m doing, or anybody better to do it with.”

I said, “It seems strange to me, as an American, but most English people appear to consider the Beatles a national asset, and the Stones a definite liability.” The driver glanced at me again, very much like a rooster eyeing a shoelace. “Exactly. The Beatles have some funny ways, of course, meditation and all that, but at least as far as appearances go, they seem to be decent chaps. But the Stones—the look of them, and the way they carry on, with their drugs and young girls—the Stones are absolute dirt.”

Mr. Havers had just completed his summation when Mick Jagger and Keith Richards came into the gallery. Everyone—spectators, counsel, jury—turned to look: it was as if the outlaws Cole and Jim Younger had walked into a court where Judge Roy Bean was trying their brother Bob.

Jon Jaymes came over to the couch with a Dodge catalogue and told the Stones to pick out the cars they wanted, one per Stone, free from Dodge, to be delivered soon in England and replaced each year as long as Dodge felt like it. Charlie and Keith ordered aluminum-finish Chargers, Jagger wanted a Charger in purple, Bill also wanted a Charger, Mick Taylor wanted a station wagon, and they wanted another wagon for Stu and the office.

Mick said that Keith had written about three hundred unrecorded songs. “I’ve got a new one meself,” he said. “No words yet, just a few words in my head—called ‘Brown Sugar’—about a woman who screws one of her black servants. I started to call it ‘Black Pussy’ but I decided that was too direct, too nitty-gritty.”

Stu, playing piano, was complaining: “I do wish Keith knew something about chords. I’m tone deaf, I couldn’t tune a guitar if I had to. I can hear changes but not what they are. Bill pulls a lot of things together because he has a good ear and knows chords. So I wait for him to get the tune together and get the chords from him. Keith gets upset if you ask him about chords because he plays three notes of a chord and doesn’t know what it is.”

Later, in the control room, listening to the last playback of “Wild Horses,” Keith would tell Dickinson, who’d asked, that he had written the chorus and Mick had written the verses. “That’s usually the way it works,” he said. “I have a phrase that fits what I’m playin’—like ‘Satisfaction’—I had that phrase and Mick did the rest. I wrote this song because I was doin’ good at home with my old lady, and I wrote it like a love song. I just had this, ‘Wild horses couldn’t drag me away,’ and I gave it to Mick, and Marianne just ran off with this guy and he changed it all round but it’s still beautiful.”

Dickinson had written out the chords in numbers the way Nashville studio players did. “Where’d you get that?” Wyman asked, looking at the chord sheet. “From Keith,” Dickinson said. He had taken Keith’s first chord as the “one” chord, putting him in a different key from the one the song was in. “Don’t pay any attention to Keith, he doesn’t know what he’s doing,” Bill said. He wrote a chord sheet that left out the passing chords and gave it to Dickinson, who put it up on the piano’s music stand, from which Mick Taylor took it away.

“Unions ain’t no good,” Tony said. He had not been arrested after all and was standing by holding the dope. “He says he can’t play, and he’s standin’ here, a piano player,” Charlie said. “Ridiculous. We can’t play either, legally.” “Why not just ignore the union rules?” Tony asked. “Disc jockeys won’t play nonunion records,” Dickinson said. “But we’re doin’ it,” Charlie said. “We’re here playing.”

Jimmy Johnson, who had been engineering the regular studio sessions in the day and the Rolling Stones undercover work at night, was still at the board, playing back tapes. “How do you keep going, man?” Keith asked him. “Courage,” Jimmy said. He had taken, to my knowledge, no drugs.

I went back to speak to Keith, who gave me the cocaine and the gold bamboo and said, “Take this.” “Why, thanks.” I went into the toilet and came back refreshed to find Keith, now in the first-class compartment, engaged in conversation with an advertising executive in a business suit. “You’re not free, man, you’ve got to do what they say,” Keith said. “You have to play what people want,” the man said. “What’s the difference?” “No, we don’t,” Keith said. “We don’t have to do anything we don’t want to do. I threw my favorite guitar off the stage in San Francisco.” “You can’t do that every night,” the man said. “I can do it as often as I feel like it. Not always but sometimes.” The man turned to me: “Do you believe this guy?” “I believe him,” I said. “Ah, you know what my scene is,” Keith said to me. “Well,” the man said, “what I do isn’t bad, I’ve never hurt anybody.” “How can you be sure?” Keith asked, and then went on as if he didn’t want to think about that one too long himself. “The problem is when you’re talking you think you’re arguing with Spiro Agnew, and you’re not, you’re talking to a perfectly reasonable man. But I really think it’s true that you can’t do what you want to do. So many people aren’t doing what they want to do.” “Most of us do both,” the man said. “We like what we do but we have to make money. It’s a compromise.” “But that’s so sort of sad,” Keith said. “But the world is not perfect,” the man said. “No,” Keith said. “The world is perfect.” At that I had to reach over and kiss Keith on top of the head, a gesture of blessing that did not even bring a pause in the conversation. “You guys work so hard,” he said to the man. “We work hard in concentrated periods but then we stop and it’s four months of doing nothing—” “It’s a different schedule,” the man said. “Yeah,” Keith said, “but most people don’t dig their work. Americans are into a very freaky scene—like Spiro trying to speak for the people and he can’t because most of the people are under twenty-five and into a very different sort of scene—” “Are you sure they disagree with Spiro?” the man asked. “I’ve just been talkin’ to those guys, those kids who’re goin’ into the army at Fort Bliss—strange name for an army camp—they don’t want to do anything but go to Juárez and score some marijuana.” “Don’t they care about girls anymore?” the man said. “Yeah, they all want to go to Juárez and screw some broads and smoke some dope. They signed up for four years so they won’t have to go to Nam and fight in a war they don’t believe in, for this idea of America as the policeman of the world.” “It’s not a matter of being a policeman, it’s a matter of protecting your interests,” the man said. “What interests, you got half a million soldiers in Vietnam which is certainly not yours. The North Vietnamese are right and they’re gonna win.” “You know that?” “Yeah, because I’ve seen films and read about it and talked to people who’ve been there.” “Yeah, but you don’t know, you might have to fight yourself someday,” the man said darkly. “I do, all the time,” Keith said, and then he seemed to despair of being able to get his point of view across to the man. “You don’t know what it’s like.” “What what’s like?” “Being a Rolling Stone, the attacks people have put on us, the violence—” “You mean people try to beat you up?” “They try to kill me, man, that’s what I mean by violence, cops have pulled guns on me and offered to shoot me with them.” “Where?” “Backstage in dressing rooms, for nothing, for the slightest pretext. The five members of this band have had to go through so much bullshit—” The seat belt light went on and I went back to my seat, passing Mick and Charlie. “But in a love affair,” Mick was saying, very earnest. I knew which five members Keith had meant. The Stones were so funky that one of them was a dead man.

As we walked out to the limousines a small boy asked me, “Are you a Beatle?” “Yes,” I said. “What’s your name?” “Philo Vance.” “They’ll believe anything,” Keith said. “Philo Vance, the well-known Beatle.” Keith and I got into a limousine and Jon Jaymes followed us, talking about the free concert. “I’m insuring the whole thing,” he said. “What does that mean?” Keith asked. “That means if there are ten murders, I go to jail.”

His heart was achin’, head was thumpin’ / Little Jesse went to hell bouncin’ and jumpin’ / Folks, don’t be standin’ around little Jesse cryin’ / He wants everybody to do the Charleston whilst he’s dyin’ / One foot up, a toenail draggin’ / Throw my buddy Jesse in the hoodoo wagon / Come here, mama, with that can of booze / It’s the dying crapshooter’s—leavin’ this world— / With the dying crapshooter’s—goin’ down slow— / With the dying crapshooter’s blues. —Willie McTell, “The Dying Crapshooter’s Blues”

Decca refused to release the album with that cover. “The record company is not there to tell us what we can make,” Mick had said. “If that’s the way they feel about it, then they should make the records and we’ll distribute them.” At last the record was released with a white cover designed as an invitation. “We copped out,” Keith said, “but we did it for money, so it was all right.”

John Lewis, a young English friend of Brian’s, would tell me sometime later that while in Ceylon Brian consulted an astrologer—supposedly, at one time, Hitler’s astrologer—who told Brian to be careful swimming in the coming year, not to go into the water without friends.

After Altamont, when I was living in London, I talked many times with Shirley Arnold, who was still running the fan club. She was one of the most decent people I had ever met, English in the best sense of the word. A few years later, when the Stones were living abroad and she never saw them anymore, she stopped working for them. She would spend a few years working for Rod Stewart and then one day she would call Jo Bergman in California, where Jo was working for Warner Bros. Records, and say, “I’ve left the business.” It was to her credit that she had never been in the business.

An audience of a quarter of a million had been expected for the Stones’ free concert in Hyde Park, but there may have been twice that many. Sam Cutler, who worked for Blackhill, was master of ceremonies. The English Hell’s Angels, younger and much gentler than their American counterparts, acted as security, as they had at other such concerts, receiving a note of thanks from Jo Bergman for the Stones: “You really did good on Saturday, you helped make it possible for us to do our thing and it really knocked us out to see your pretty smiling faces.”

Charlie was looking away, distracted, as if he weren’t seeing the buildings rush past. “Brian had a whole trunk full of jewelry,” he said. The contents of the trunk, like most of Brian’s possessions, had disappeared after his death. “It was like pirate treasure, a whole trunk full of little trinkets.”

While the luggage was shifted into the helicopter, Mick led the film crew around the pier. Among the people watching was a fat, blond, white-stockinged, cross-eyed groupie. “Charlie,” Mick said, “get in the film, Charlie.” “Kiss the girl,” the cameraman said. “No,” Charlie said. “On the cheek.” “No,” Charlie said, with his turned-down smile. “Love’s much deeper than that, it’s not something to be squandered on celluloid.”

We descended at a crazy angle to a spot a long way up the hill behind the stage, coming down with a bump. The doors opened and we were out-side in the crowd. Mick and Ronnie got out first and a boy ran up to Mick and hit him in the face, saying, “I hate you! I hate you!” I couldn’t see it, I just saw a scuffle and heard the words. I grabbed Charlie and held on to him, because I didn’t want him to get lost, God knows what might happen to him. I don’t know how Mick and Ronnie and little Mick moved so fast, but they disappeared, leaving me with Jo and Charlie Watts, the world’s politest man. I tried to move him through the sea of sleeping bags, wine bottles, dogs, bodies, and hair. Like a mule in quicksand, he didn’t want to go forward, didn’t want to go back. “Come on, Charlie,” I would say. “Just step right on them, they don’t mind, they can’t feel a thing.” The ones who were conscious and moving about said, “Hello, Charlie,” and Charlie smiled hello.

Michelle Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas came into the trailer bearing tales of how the Angels were fighting with civilians, women, and each other, bouncing full cans of beer off people’s heads. Augustus Owsley Stanley III, the San Francisco psychedelic manufacturer, known as Owsley, was giving away LSD, the Angels eating it by handfuls, smearing the excess on their faces. It didn’t sound good but there was no way to do anything about it, nothing to do in the center of a hurricane but ride it out.

“He’s really very nice, you know,” Charlie said to me, talking about Gram. “I’ve been talkin’ to him about San Francisco, and the hippies and all that, and he’s got standards, he goes just so far and no farther. And when that girl came in, he stood up just naturally without thinking about it.”

I sat on the grass in a corner of the tent with Gram, who was talking as if we were about to leave high school forever. “I really liked what you wrote about our album. Would you write me a letter sometime, I’d sure like to have a letter from you.” “Sure, soon as I get the chance,” I told him. I never got the chance. “The lines you quoted about not feeling at home anywhere—that was really good, it was really where I was at when we did that album.”

Jon Jaymes waddled in, giving the Angel at the tent flap a sad look, and I eased over to hear his news. “There are four Highway Patrol cars,” he told Mick. “Those are the only ones available to take you to the airport. We can have them right at the back of the stage, so when you come off—” Mick was shaking his head. “Not with the cops,” he said. “I ain’t goin’ out with the cops.” “I knew you’d say that,” Jon said. For some reason, as he stood surrounded by Hell’s Angels in the world’s end of freakdom denying the only safe way out, I was proud to know Mick Jagger, and I put my arm around his shoulder, on his orange and black satin batwinged outfit, nodding my head in agreement. We looked at each other and began to laugh. “Where’s the stage?” Mick asked.

I had seen Angels before, and en masse they were just as lovely as I’d expected, filthy boots and jeans or motorcycle leathers, one bearded specimen wearing a bear’s head for a hat, looking as if he had two ferocious grizzly heads, one on top of the other.

Mick stopped singing but the music chugged on, four bars, eight, then Mick shouted: “Hey! Heeey! Hey! Keith—Keith—Keith!” By now only Keith was playing, but he was playing as loud and hard as ever, the way the band is supposed to do until the audience tears down the chicken wire and comes onstage with chairs and broken bottles. “Will you cool it and I’ll try and stop it,” Mick said, so Keith stopped. “Hey—hey, peo-ple,” Mick said. “Sisters—brothers and sisters—brothers and sisters—come on now.” He was offering the social contract to a twister of flailing dark shapes. “That means everybody just cool out—will ya cool out, everybody—”

“Either those cats cool it,” Keith said, “or we don’t play. I mean, there’s not that many of ’em.” It was a fine brave thing to say, but I had made up my mind about fighting the Hell’s Angels while one of them had me in the air, and probably the rest of the people present had concluded some time ago that the first man who touched an Angel would surely die.

Later Michael wrote of the Angels, “Their absolute solidarity mocks our fearful hope of community, their open appetite for violence our unfocused love of peace.” At the time I thought, Notes? He thinks I’m taking notes?

You felt that in the next seconds or minutes you could die, and there was nothing you could do to prevent it, to improve the odds for survival. A bad dream, but we were all in it.

“Aw yeah,” Mick said as the song ended. “Hey, I think—I think, I think, that there was one good idea came out of that number, which was, that I really think the only way you’re gonna keep yourselves cool is to sit down. If you can make it I think you’ll find it’s better. So when you’re sitting comfortably—now, boys and girls—” withdrawing the social contract—“Are you sitting comfortably? When, when we get to really like the end and we all want to go absolutely crazy and like jump on each other then we’ll stand up again, d’you know what I mean—but we can’t seem to keep it together, standing up—okay?” In the background Keith was tooling up the opening chords of “Under My Thumb.” A few people in front of the stage were sitting, going along with Mick, who for the first time in his life had asked an audience to sit down. The anarchist was telling people what to do. Then, just before he began to sing, he said, “But it ain’t a rule.”

“Thank you,” Mick said to the crowd. Charlie was playing rolls. “Thank you. Are we all, yeah, we’re gettin’ it together—we gonna do one for you which we just ah—” pausing, remembering that making the record was breaking the law “—we just ah—you’ve never heard it before because we just written it—we’ve just written it for you—”

Mick played soft harp notes that trailed off as, head bent over the mike, he began singing lullaby phrases, trying to soothe and gentle the great beast. “Aw now, baby baby—hush now, don’t you cry.” His voice was tender, a tone of voice that Mick Jagger had never before used in public and maybe never in his life. “Hush now, don’t you cry—”

The band started “Honky Tonk Women,” playing as well as if they were in a studio, Keith’s lovely horrible harmonies sailing out into the cool night air. Nobody, not even the guardians of public morality at Rolling Stone who pronounced that “Altamont was the product of diabolical egotism, hype, ineptitude, money manipulation, and, at base, a fundamental lack of concern for humanity,” could say that the Rolling Stones couldn’t play like the devil when the chips were down.

We climbed out and as Keith, walking under the blades, headed for the airport building, he was denouncing the Angels: “They’re sick, man, they’re worse than the cops. They’re just not ready. I’m never going to have anything to do with them again.” He sounded like an English public school boy whose fundamental decency and sense of fair play had been offended by the unsportsmanlike conduct at soccer of certain of his peers. Mick sat on a wooden bench in the little airport, eyes still hurt and angry, bewildered and scared, not understanding who the Hell’s Angels were or why they were killing people at his free peace-and-love show. “How could anybody think those people are good, think they’re people you should have around,” he said. “Nobody in his right mind could,” I said, “that’s why—” I started to say, That’s why I said last night that you believe too much of the hype, but I didn’t. He had paid for his beliefs and nobody had the right to condemn him.

“We wouldn’t even be here if it wasn’t for you,” Gram said to me. “Thanks a lot.” “It was nothing,” I said. We grew quiet as we approached the hotel. It was beginning to dawn on us that we had survived.

Talking on the phone to a radio station, Mick said, “I thought the scene here was supposed to be so groovy. I don’t know what happened, it was terrible, if Jesus had been there he would have been crucified.” When he was off the phone, he said that he was down on the idea of the movie. “I don’t want to conceal anything,” he said, “but I don’t want to show something that was just a drag.”

At four in the morning we were still sitting around. Charlie usually went to bed early, but tonight none of us wanted to be alone. A scratchy old blues record was playing on Keith’s tape recorder. “Can you get that line there?” Mick asked me. “What’s he saying?” I listened, but there was too much surface noise, the message was lost. “I can’t get it,” I said. “Something about God and the Devil.” “I’ll play it back,” Mick said. I listened again. “I still can’t get it.” I was so tired that my ears were not clear. “But it’s the point of the whole song.”

I spent time with the Stones on later tours, and they were always good, but there never seemed to be so much at stake. There was, though, just as much at stake, but it was harder to see. For one thing, we were never again in the desert, beyond all laws.

Why did it take so long to write the book? I had to wait for the statute of limitations to expire, I’ve said, but that wasn’t the main reason. I had to become a different person from the narrator in order to tell the story. This was necessary because of the heartbreak, the disappointment, the chagrin, the regret, the remorse. We had all, Stones, fans, hangers-on, parasites, observers, been filled with optimism there in the autumn of 1969, optimism that the following years proved completely unjustified. In our private lives as in the public life of our time, we were disappointed, by others and by ourselves. This is I expect the experience of all generations, but we believed that we were different, that we were somehow chosen, or anointed, for success, for love and happiness. We were wrong.

It was as if, in response to that event, the young men of the time got into their vans with their big ugly dogs and stringy-haired female companions and, reeking of patchouli, headed for the hills. I did a version of this myself, going to an Arkansas Ozark cabin for the better part of a decade. Like my contemporaries, I tried to forget about saving the world. But I had this story, this burden to carry, and I couldn’t let it go.

Part of the reason the book remains to this day little more than a rumor is the way it was published, as a sort of cross between a fan rag and serious cultural history. If it’s well written, let people find out later, I advised, not being optimistic enough to believe that many readers, certainly the ones who had any interest in the Rolling Stones, purchased books based on the quality of the writing.

I tried to make every sentence one that could be spoken by Chandler’s detective narrator Philip Marlowe.) Ultimately I typed the pages on an Adler, which I understand is the kind of typewriter Hitler had, a very good one.

My agent suggested I accept the lowered advance. In a lifetime he might do hundreds of books with the publisher, a few or maybe even only one with me. I, desperate, went along, handing over half the manuscript and receiving another eight grand—and that was pretty much the extent of my fiduciary compensation for telling this tale.

Back at my house in Memphis for a visit some years later, I received a letter from the agency informing me that the publisher had formally requested delivery of the manuscript, a preliminary to demanding return of the advance. My response was to go into the kitchen for a butcher knife, get a pillow from the bedroom, slice it open, take a handful of feathers, fold them into a sheet of typing paper, stuff it into an envelope, and send it to the agency. Then I went back to the hills, where I made the manuscript as close to unreadable as I could out of paranoia—maybe—because I would rather have died than let go of it before it, not I, was ready. I thought it might be the last thing I ever did, if I ever managed to do it, and I wanted it to be right, or as close as I could make it.

A note on the title of the first hardback edition—I’d called the book The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones all the (considerable) time I’d been writing it. Some genius at the publisher’s got the inspired notion of calling the first hardback edition Dance with the Devil. (Editors don’t generally give a damn what writers think their books should be called, and in any case are without exception frustrated writers themselves, desperate to demonstrate what they sincerely believe to be their superior creativity. Young, unpublished writers should consider yourselves warned.)

Writers can’t get on television. That’s the rule. At that point, 1985, only Truman Capote and, rarely, Norman Mailer and Gore Vidal could wangle airtime. William Styron, Philip Roth, James Jones, Kurt Vonnegut, everybody else could forget it. I had been offered a literally golden opportunity that my publisher’s publicity people had simply tossed into the waste-basket. I told all this to Wexler. “You’re fighting,” he said, “what I call the battle of the building.” “But Jerry,” I said, full of my ignorant self as usual, “if these people promoted this book, it might make some money. Why wouldn’t they want to make money?” “What you’re saying does not obviate the truth of my contention,” Wexler went on placidly. “Somewhere in that building there is a man. And the man has not done this.” He demonstrated with a mighty nod. “If that man should make that gesture, these people who you think are so incompetent would amaze you with their ability to take care of business.” That did it. I knew I was sunk for the length of that contract. Nothing to do but go home and write another book.

|