Alexander the Corrector (1934)

by Edith Olivier

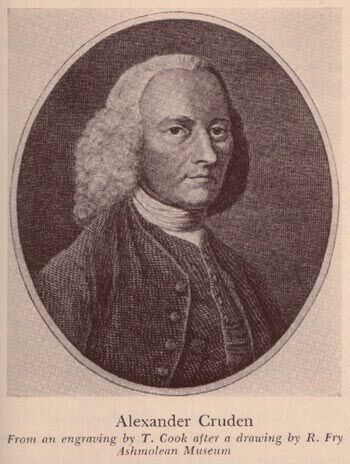

The story of Alexander Cruden, compiler of the famous Cruden's Complete Concordance to the Old and New Testaments, presented here in bite-size format:

The story of Alexander Cruden, compiler of the famous Cruden's Complete Concordance to the Old and New Testaments, presented here in bite-size format:

-

The Grammar School boys of course had no Christmas holidays. Masters and scholars were sternly

commanded to attend throughout "the superstitious time of Yuill." (8)

-

But he loved the nameless girl for herself, and that broken romance broke something in his

brain. (13)

-

All through his life, the most tiresome thing about Cruden was his persistence. No doubt this

trait helped him to compile his Concordance, but in social life it made him very trying. It was

impossible to snub him, for though he saw a snub clearly enough, he never took one. (13)

-

He had now fallen in love with the daughter of an Aberdeen minister, but she did not care for

him. He could not believe this, for the deduction he drew from his Calvinistic creed was that

the desires of the Elect necessarily coincide with the Will of God. He had fallen in love:

therefore, he argued, the girl he loved must be predestined for him in the age-long counsels of

the Almighty, where it was decreed that Righteousness and Peace should kiss each other. But the

girl did not want to kiss Alexander, and in his ingenuous optimism he mistook her refusal for a

pleasing modesty. He would not let her alone. (13-14)

-

Unhappy Cruden! Unhappy lady! He should have known better than to love her. (15)

-

So she passed out of his life. Of her own will she had played no part in it. He had never meant

anything to her. She had suffered misery and shame, and Alexander Cruden was now only a

half-forgotten and rather ridiculous figure appearing from the days of her girlhood in

Aberdeen.

But it is his cry of despair alone which makes her live for us. (16)

-

[T]hen followed Lord Derby's first experience of the linguistic powers of his French Reader.

Alexander was given a French book and the unhappy listener heard the words spelt out one by one

after Cruden's extraordinary manner of reading French. (28)

-

Mr. Frederick accordingly gave the coup de grace on July 7th. He did it as kindly as he

could, telling Alexander that he was agreeable to his lordship in every way except in his

pronunciation of French; but that, as his position in the household was solely that of French

Reader, dissatisfaction with him in that capacity meant that he could not stay. (32)

-

The persistence which was a dominant note in his character, and which had made him such a trial

to Lord Derby and his servants, was now his great asset. His whole life had been a preparation

for this. (56-7)

-

Was there ever, before or since the year 1737, another enthusiast for whom it was no drudgery,

but a sustained passion of delight, to creep conscientiously word by word through every chapter

of the Bible, and that not once only, but again and again? (57)

-

There was only one man living who could enjoy doing this; and he was the man who had not been

able to believe that Lord Derby might be bored when he heard a French book read aloud one

letter at a time. (57-8)

-

The word most commonly used to describe Cruden's Concordance is "invaluable," and this it

certainly is. No other word is needed, for there is nothing more to be said. If you want to

look up a reference in the Bible, you must have Cruden's Concordance at your elbow: no other

book will do. If you never have this desire, Cruden can do nothing for you. He is either

invaluable, or he is completely useless. (58)

-

If Cruden was a madman, he was a remarkably clear-headed one; and the strongest brain might

well have flagged when a work like this came to an end. (60)

-

He knew himself famous. (63)

-

[T]hree months before the Concordance was finished, Mr. Pain had died. His wife was now a rich

widow, and as the months of that hard winter went by, Alexander began to see her in a new

light. He was lonely and poor: Mrs. Pain could satisfy both these needs. He kept thinking about

her. That comfortable house: that kind Christian woman: the security of that steady income --

he knew that these were what he wanted. He was in love. (86-7)

-

It was some time before it occurred to her that he could really consider himself as a possible

husband for her; and, when the idea did strike her, it did not please her. Alexander opened her

eyes by what he called an awkward "piece of love gallantry," and she gave him a snub. As usual

he refused to take it, but he was extremely annoyed. Cruden was quickly offended; but when he

was offended he always pursued with increased ardour the person who had offended him, and who

so had aroused his sporting spirit. (87)

-

[T]he coach rolled relentlessly on, never stopping until its frightened, frenzied occupant was

put down at the door of Mr. Wright's Private Madhouse in Bethnal Green. (94)

-

It is almost incredible that Wightman should have been exonerated. He had presented Cruden with

the alternative either of signing the papers which absolved the Blind Bench from all blame,

whatever they did; or of being chained to his bed and being sent to Bedlam if he refused. This

seems a particularly horrible form of blackmail. Madman or not, Alexander's treatment was

illegal and brutal, and he must have won his case if it had been properly presented.

He bore his disappointment calmly and well. (128)

-

Alexander had lived so long alone that he found his sister rather a trying companion. She set

her opinions against his, and he deplored her "imaginary infallibility and real obstinacy." As

he shared both these characteristics, their wills constantly clashed. (130)

-

About this time he began to call himself "Alexander the Corrector." This was a play on the word

and it gave him great pleasure. He had made his name as a corrector of proofs, and now it had

been brought home to him that there awaited him something more than proofs to correct. He had

always believed himself marked out for some high vocation. (132)

-

And then he came upon a street brawl. Such scenes always attracted him. This gentle stuttering

little man, so fearless and so confident in his divine mission, often intervened in street

quarrels. He would walk between the fighters, and surprise them into standing still to hear

what he had to say. They admired his courage, and his eccentricity made them laugh.

But this time he was not to be successful, for before he had time to make his voice heard

amidst the uproar there swooped down upon the scene a young man armed with a shovel. His

language was so obscene that Alexander could not tolerate it. He wrenched the shovel from the

hands of its owner, and proceeded to whack him soundly upon the head with it. (136)

-

He knew too well that he was being carried to a madhouse, and he told her so with a directness

which made her ashamed. They all admired the calmness and courage with which he stepped into

the coach, "as if he had been to set out on a pleasant journey." (141)

-

Alexander's patience now came to an end, and he said dramatically:

"I am like Alexander the Great, who used to set up a piece of candle before a town. If they

submitted before it went out, they had safety and protection. If not, they were put to the

sword. Beware now. If you do not take these reasonable terms, I'll go to Law, and sue you for a

thousand pounds." (147)

-

He was possessed by a new idea on the subject of the Corrector's office. He remembered having

learnt in the Grammar School at Aberdeen that the ancient Romans had an office which might with

advantage be revived, even in a Christian state. "Their censors or correctors of the people

were reckoned prime Magistrates.... As the consuls were too much taken up about other matters

to be at leisure to look near enough into the behavior of the people, a person of good

character was elected into the office of censor.... A great part of his business was to inspect

and correct the Manners of the People."

This was exactly what Alexander wanted. As a Scotchman, he had already looked near enough into

the behaviour of the English to observe their many failings in manners and morals; while as a

lover of sermons, he was delighted to find an office which gave its holder the right not only

of preaching, but of enforcing the practice of what he preached. (153)

-

A parliamentary election was pending, and he resolved to become a candidate for the City of

London. As a high member of the House of Commons, he would have as much weight as if he had

received a knighthood. (159)

-

One day before the election, Cruden hoped to persuade Sheriff Chitty to arrange for him a

meeting with the other candidates, thinking, in his simple way, that if they could hear his

lofty motives in coming forward, they would one and all stand down, and allow his unopposed

election. He dreaded the prospect of a poll. (160-1)

-

The eccentric Cruden was three times confined in a lunatic asylum -- in 1720, in 1738, and in

1753 -- and each of these confinements coincided with a love affair. (164)

-

Meantime, lest she should forget him altogether, he sent her copies of both parts of his

"Adventures," the pamphlets which told the story of his incarceration in the madhouse at

Chelsea; although these records can hardly have improved his chances as a suitor. (171)

-

Lunatic as he was at this time (and he was certainly madder now than at any other part of his

life), he was at his maddest a very harmless lunatic. Nothing was to be feared from him.

But it is true that he was more than half crazed by his absorption in the Bible, for his was

too matter-of-fact a mind to venture safely upon its spiritual pinnacles. Like other

enthusiasts before and since, who have twisted the Scriptures to suit their own

interpretations, he was both ridiculously literal and seriously fanatical. (173)

-

He now asked for an Act of Parliament to constitute him Corrector of the People, with power to

"restrain profane swearers, Sabbath breakers, lewd men and women, and other notorious sinners,

in accordance with the laws of God and the nation." (183)

-

He had arrived intending to "put a stop to profane swearing, Sabbath breaking, and partyship";

but the Vice-Chancellor told him that he "would be a greater Conqueror than Alexander the

Great, if he succeeded in these three things." (185)

-

As it had always been impossible to succeed in snubbing Alexander, so too these merrymakers

found that they could not make him the butt of a practical joke. He cut away the ground from

under their feet by joining with them, and playing it more wholeheartedly then any of its

perpetrators. (189)

-

He was a philanthropist and a missionary, an egoist and an enthusiast. He was a true Eccentric,

for his ways were not concentric with the circles among which he moved: throughout his life he

followed his own orbit. (235-6)

-

In his will which he made in Aberdeen six months before his death, Cruden asked to be buried

with his parents in the graveyard of St. Nicholas' Church, not far from the house where he was

born. This was not to be. Instead they laid him in the burial-ground of a dissenting

congregation in Dead Man's Place, Southwark. The cemetery has disappeared and is now part of a

brewery. Brewers' drays clatter, and beer-barrels rattle, over the grave of Alexander Cruden.

(243)

Buy Alexander the Corrector

|

![]()

![]()