House by the Buckeye Road

Helen H. Seargeant (1960)

None of my immediate family ever lived in Buckeye, but my cousin, Tom Shultz, lived there at one time, and in the early nineties he edited a newspaper that was, by report, "about as big as two postage stamps"; he named it the Buckeye Blade. The little town of Buckeye does not figure very strongly in this writing, but if there had been no Buckeye there would have been no Buckeye Road, and therefore I make mention of it. (ix)

He looked quite the country gentleman as he handed me a box and said, "I thought you would like to try some of our cactus candy. They make it heah in town," and that was nice going, considering his evident shyness. (3-4)

Coming back with them to Phoenix, there was only the branch line in from Maricopa on the main line then, and the little train backed all the way in and around by Tempe—and that day I had my first sight of our old Camelback Mountain, and the "Hole in the Rock," from the train windows. (4-5)

Phoenix again—8 o'clock in the morning of a day in June, 1911, and it was warm when I got off the train at the station.

I was expecting V.S.S. to meet me, as I had sent him a telegram the day before, but there was no V.S.S. in sight. There wasn't anybody in sight but one old man with a little one-horse wagon, resting in the shade of a cottonwood tree back of the station and waiting for customers. The sun was exceedingly bright and everything around the station glowed with the heat—even at 8 o'clock in the morning—and I began to be very warm and uncomfortable. Walking around on the little wooden platform while I waited, I was reminded of my father's opinion of Phoenix. "I wouldn't live in Phoenix if they gave it to me," he had said, and here I was, considering the possibility of staying awhile in this place. (10)

It wasn't quite so hot trotting along the country lanes, but I still felt too warm, and when I mentioned the weather he said, "Oh, no. This ain't hot yet. July an' August them's the hot months. This is fine weather now. Nights still fine an' cool."

"But how do they stand it if it gets so much hotter than this?"

"We-ell," he said, "you kinda get used to it, an' it ain't the kinda heat that hurts people. They don't get sunstroke here like in some o' them eastern states. It's the dry climate that does it, they say. Lots o' people come here for their health. Lots o' lungers, too. It's a fine place fer them. They come out here an' live in little shacks around the country an' some of 'em take up a homestead claim out in the brush—scratch a little patch uv ground t' comply with guverment regalations—an' build some sort of little shack, haul water in barrels and camp out in the dumdest lonesomest places you ever see ... " he spit tobacco juice accurately out over the wheel, "an' most of 'em git well. Lots o' fresh air and sunshine. They git as brown as Injuns. Docs say the germs can't live in this dry, hot air." (11)

"And," I asked, "is that hump-backed red mountain over there the Camelback?"

"Yep," said he, "that's it. There's some as fancies it looks like a camel kneelin' in the dessert [sic]—an' if you look at it jist in the right direction it does look a little like. That's its head layin' over there on the left. Over in them big rocks over there," and he pointed more east, "there's the Hole in the Rock. Ye can see right through to the sky if you git in the right place. They go out there fer picnics a lot." (12)

All that day it rained, and V.S.S. said, "This is no summer thunderstorm. It looks like it might hold on for some time. Of course," he went on with sarcasm, "the natives will say it never happened before. I never saw a place yet where the weather wasn't perfectly extraordinary. The hottest spell—the coldest snap—the biggest rain, etc., in twenty years. . . ." (16)

Being in good health, it didn't bother me much except to make me uncomfortable, but poor V.S.S. suffered from the heat. He would come in from work, groaning to get to the ice water to cool himself off—and that would make it worse than ever, though he wouldn't believe me when I told him he should drink warm water. (19)

Then, in the summer (there were no coolers in those "good old days") we stewed in the heat, and it was hard to keep going through the afternoons. The mosquitoes came through holes in the screen on my tiny sleeping porch at the Griswold's, so I bought mosquito dope to rub on my hands and face—and went to sleep holding the open bottle and spilled dope all over me. Mr. Griswold snored loud and long on their screen porch below me, and I wished all my mosquitoes would go down and pick on him. (21)

She had some Christian Science mental quirks that were funny, too. I kept an office key, as I generally got to the office before anyone else did, and one day the bunch of keys on which I kept it seemed to be lost. When she heard the keys were lost she said to me, "Jist say, 'Lord, them's my keys, and I want 'em!' " Maybe her earnestness on the subject did something, for next morning I found them. (23)

Mr. Griswold had a bicycle shop downtown; he was a good old man, who would do anything he could afford to do to make one happy. He really couldn't help snoring at night, and probably didn't know he did it. (23)

When I wanted to take down his name for my boss, I had to make him spell it before I could make it out. It is, you know, one of those "specknoodle" names, that you can't really believe when you hear it. I never did get to see what Mr. McAdoo looked like, because when he did come in, I was out. (You don't know the "Specknoodle" story? It was just that—a funny story about a young man who was introducing the gentleman to a deaf aunt. "Aunt Emma, this is James Specknoodle." Auntie cupped her ear and said, "What is it George?" "Specknoodle," says George, and louder, "SPECKnoodle." Aunt Emma shook her head. "It's no use, George. It still sounds like Specknoodle.") (25)

My eyes were so full of dust I couldn't see, and I had to hold my hat and chew grit. (28)

I shall never forget the trails through the desert brush and greasewood across the Agua Fria. They ran diagonally, cross lots, or any old way, in the unapparent business of getting to a given point. Unapparent, because they had a fancy-free way of skirting draws and curving this way and that around clumps of brush or mesquite that gave them an allure and charm I never find in the cement ways. Cement roads are faceless, characterless strips, that bring on a most uncivilized carelessness for life and limb, and a contempt for everything but speed, but the quiet byways through the brush were always a joy to me. (34)

One of John's men used to start the water on one of those strips between the borders (they called them "lands") and then he would go about halfway down that land, stick his shovel straight up in the ground, pick himself a place a few yards below the shovel and lie down to sleep. When the water reached the shovel and softened the earth around it the shovel would fall down and waken him—maybe. (39)

Mrs. Smith was from the East, and when she looked out of the kitchen window in the morning and saw the men harnessing up the mules out in the lot, she was almost overcome by the size and grandeur of the mules—at least, she made it sound that way. Such a lot of "Ohs" over the "big strong mules," the kind of behavior my mother used to call "taking on" over things. Mrs. Smith didn't know a thing about mules, but she was a good "taker on," and I noticed it pleased and amused the big man. (41)

Of all the hardships pioneers had to put up with, I am sure that old washtub business was the worst, and the women got the brunt of that. The man had his hard and dirty work in the field, but it was creative work and important business, and he was a big man, and he swelled with pride over a good crop when he had achieved one. The woman did her big work cleaning the clothes, and the man just took them out and rubbed them in the dirt again. If she could have saved up her credits for about six months so she could exult over them in a pile, she might have felt that she had accomplished something worth while; but, no, at the end of that six months all she had was the same little old pile of clothes—decidedly worn—and probably dirty again. Heck! Civilization wasn't worth it. (44-5)

I remember her laughing once about a remark one of John's cousins made about our housekeeping. She and Aunt Chip (John's aunt), and one of John's cousins from Los Angeles had driven out to call on us. The cousin had chanced to look into the kitchen and saw the table set for a meal. On their way back to town he had said to her, "Why they are just camping, and I thought they lived there." City dude! He actually didn't know that it is quite possible to live right at home with camp dishes and think nothing of it. (47)

My father used to tell me about sheep sense (unsense), he having been a sheepman during my early youth. He said that if a herd of sheep are driven through a gate with the lowest bar still up, the first sheep will jump the bar, and after a few sheep have jumped the bar, you may remove it, and the rest of the sheep will go on jumping the bar that isn't there. (People are that way, too, about a lot of things, and don't even know it.) (57)

We were afraid the wind would blow the tank off the skids, and John stopped operations and tied down the guy wires. I was glad, because it was jittery work for me, with an heir on the way, to be driving a derrick horse in a storm. (67)

The Stone family lived on the Buckeye Road comer, where Perryville developed later. One summer their little wooden box house blew over in one of those extra hard evening dust storms. (69)

This was the first of a long line of Model-T Ford cars that my Johnnie never tired of. John came out from town in the little automobile when he had finished the trade, and after that there was no holding him. Instead of getting home earlier, when he went somewhere he always went so much further than he used to do with the horse and buggy, that now he was just as late as ever getting home. (70-1)

The Pan American Ostrich Company had been incorporated in 1906, (Incorporators: H. B. Wilkinson, J. W. Crenshaw, F. H. Ensign, W. C. Hornberger), but it broke up and dissolved long before the expiration date of their charter. When the Ostrich Company's farm here went out of business, people said it was because feathers went out of style. If that is true it is possible that the automobile had something to do with it. It was the day of open cars, and fine plumes are not suited to the windy air currents of open cars. Always of impractical value, they became more so when hats were to be tied on with veils and carriage head-space had to be reduced.

Whatever the reason, they did go out of business, and when they were beginning to start the dissolution of the farm's business we went over one day and looked at feathers for sale—at reduced rates. I bought several beautiful feathers just because they were so beautiful—and kept them stored away in a box till they finally fell to pieces. What use did I have for ostrich plumes—riding in a Model-T Ford car?

When the ostrich farm broke up, Dr. Chandler, of Chandler, bought quite a number of ostriches and wanted to take them to his town. He thought that if they had enough cowboys to handle them they could drive his ostriches to Chandler, as they would drive a herd of cattle. (75-6)

There were fences on both sides of the road for several miles east of us, but when the fences gave out there were no barriers, and the ostriches broke away and scattered every where. They couldn't get them bunched again. . . . (76)

There were a number of accidents caused by runaway teams when they were frightened by ostriches, and Mr. and Mrs. Rousseau, an elderly couple from Alhambra district, were thrown from their buggy and killed when their horse was frightened by one of those roaming ostriches.

Frank Hill, who lived on the Yuma Road, told us how he and his mother were attacked by an ostrich one evening, when they were driving home in their automobile. It was late enough for the car lights to be on and the ostrich began to kick at the lights. It kept fighting the car until it got the toes of one foot caught under a wheel. Then Frank managed to get it by the neck and cut its throat with his pocket knife.

Ostriches were sighted in odd places about the country for awhile, but they finally disappeared. Dr. Chandler had found out why one can't call a large number of ostriches a flock or herd. These flat-headed birds just do not have the herd instinct and no follow-the-leader impulses. When Dr. Chandler bought some more ostriches, he had them sent by rail to Chandler. It was not so hard to get them into boxcars.

There were surplus ostriches left that were for sale, cheap, but few people wanted them. They even tried feeding them to the public as a novelty meat. (76-7)

It used to be interesting at first to go see them run the heavy iron rail (piece of railroad track) over the ground—broadside, you know—to break down and drag off the brush—though I hated, every time, to see them spoil some nice, clean desert. I always like to walk over wild ground where the squawberry and catclaw, mesquite and greasewood shrubs still flourished. (77-8)

[Mesquite] is a good kind of wood to have in a country where they never build woodsheds—it takes more than one good rain at a time to wet that stuff. (78)

(All you fellows, with modern big machines for land leveling—maybe you still get dirty, but you don't know a thing about real work.) (79)

Then he gave a dig at my part of the world—"I rather think that Hell was moved to Phoenix and the Devil holds a kind of sub-agency here." . . . He always had it in for Phoenix, ever since he had, in the very early days, walked from the old grist mill on Tempe Road into Phoenix—on a summer day—and saw open meat markets, where flies swarmed unhindered by screens. (85)

For years, whenever I wanted to see whether the men were in from work and unharnessing at the corral gate, I had to run out and skip around that adobe house first. Oh, I suppose it kept me in skipping shape, and I hated to tear it down—it was historic—but even historical things can be a nuisance if you want to see through them. (87-8)

We slept on that porch a good many years, winter and summer (and I swept out mountains of duststorm leavings during those years), and don't let anyone ever make you think it never gets cold in our sunny clime here. It gets down to freezing of early mornings quite frequently in our coldest months—but we did have a good bed and would undress in the big bathroom—I guess that was one reason for the size of it—and didn't dally around out there in the cold. (89)

On the kitchen side Mr. Marshall made me a great improvement over the old style "desert cooler," those out-of-door things that were covered with barley sacks and equipped with a tank on top (that was always going dry) for a water "dripper," and so much running out of the door to get to it always let in a few flies. He made a little door in the west end of the pantry expressly for the purpose of setting the cooler there. The frame of the cooler was flush with the door frame and he screened the four-inch space between the edges of the cooler and the door frame to keep out flies and let in air—and the door of the cooler opened directly to the pantry. Those good inventors, John and Mr. Marshall, fixed a water pipe to drip on the cooler, and a nice cement base with little runway for the water to get away—made such a nice cool place near and under the cooler that I often had a nice little frog to enjoy it. It really kept things cool, except in the very hottest weather. (90)

When we had flood waters in the Agua Fria and the waters had gone down almost enough for cars to cross, Jose Juan hauled automobiles of unwise drivers through the river when they got stuck. John let him take a team of mules and gave him half of what he earned doing it. He made himself nice wages for the work and some wages for the mules. He would offer to take them through for a reasonable price. If they turned up their noses and went ahead and got stuck he would charge them five dollars to go in and get them out. Quite a number of them didn't know any better than to try it and it was seldom, indeed, that they emerged triumphantly on the other side. Jose Juan actually earned his money, though, because he had to wade in the cold river to drive the team and he was wet to the waist most of the day. (93)

"Jesus" is that other name (mentioned along with Ysabel) that is used in Mexico for either man or woman. Let me say here—for the benefit of those who may regard it a sacrilege to use the name Jesus for ordinary people—Spanish-speaking people, particularly those of Mexico, never speak of our Savior as Jesus. To them He is Jesus Cristo. Therefore, Jesus, as a name is in no way disrespectful. It is considered an honor and, it is true, I have never known a Jesus, man or woman, who was not a good and honorable person.

My Jesus was, of course, female, a fine bedmaker, and knew how to clean and dust without breaking and displacing things.

Jesus was not a pretty girl but she had dignity. She had beautiful teeth and a fine head of hair, which she kept in neat braids closely wound about her head. (105-6)

In the early days Uncle Billie and Cinthy adopted a little Indian girl. They both thought so much of her that it was a terrible shock to them when the child was killed. She loved horses; one day a teamster came, trailing a colt. She ran up to pet the colt and it kicked her in the breast, killing her instantly. Cinthy never really got over it. (119)

Her traveling turkeys were just turkeys, you know, and turkeys have no sense—homing sense, I mean. Like their wild ancestors they love to roam; they will go visiting—and if they like the place they stay. They may go to roost in your handy tree, instead of going back to any home roost. (132)

When she was on the train, the other passengers admired the baby very much; and when they learned Mrs. Hedger's destination, they took it upon themselves to tell her all about the place she was going to find. They were horrified that she would think of going to such an awful place—with that beautiful baby, too! Why, there were tarantulas and centipedes and all kinds of awfull things—and when she told them the house was built of some sort of clay (she was not familiar with adobe yet) they said, "That kind of a dirt house? Why, they're awful and the scorpions crawl all over the walls day and night," and they managed (and would you believe, it was done with kindly intention?) to cause the poor woman to be sick with fear by the time she reached Phoenix.

She told me about this years later and said that when she got to the house she was to live in, she was so surprised to find it nicely furnished, with pretty wallpaper, and with no evidence of the horrors they depicted, she was overjoyed. It was a nasty way to do it, and that probably was not their intention, but those helpful ladies may have done Mrs. Hedger a good turn, after all. To expect something awful and then find it good was better than expecting something good and then being disappointed in it. (136-7)

Lida Hedger was the only person I know who became well enough acquainted with Cinthy that she told her things about herself. (137)

Jim Ivy (James Pleasant Ivy) was the church's most upstanding elder then. My first acquaintance with Mr. Ivy was when he came to inspect my bees. He was bee inspector; it was his duty to inspect all bees for any disease or foul brood among them, so he looked at the bees, counted the hives, and charged me five cents each for (it appeared) counting them, but no doubt he could tell by looking at them that they were perfectly healthy bees. (138-9)

At Humbolt the smelter was then a busy place and we stopped in to look around a little. John got a permit from the gate-man to enter—which meant he signed a paper to the effect that if we were silly enough to get hurt we couldn't sue them for damage. They wouldn't do that for visitors in these days, but there were fewer people then; besides, we really looked intelligent, you know. (155)

We finally arrived in Prescott—and there it was: the place where I was born. I couldn't say it looked different, since I had never really "seen" it, but of course it was different. It had been a pretty thin place when I'd been there before—it lacked two years yet then for the time Bucky O'Neill was to arrive—but here now was a real town with a public square and a statue of Bucky adorning it—a fine court house, and a home for the Pioneers. (156)

Papa bought Albert a high bicycle for being a good boy in school. What he really wanted was a banjo (it happens that way often, doesn't it?) but he, at least, got more exercise out of the bicycle. He had a regular broncho bustin' time learning to ride it. It would kick up with the little back wheel and throw him over its head and down he would go, tangled in the handle bars with the bicycle on top. The more it threw him, the madder he got. He would fairly weep with rage, but he would grit his teeth and grab the bicycle and go at it again till he finally had the best of it and would go sailing gaily around Williams in a cloud of dust. (166)

Frank Rodgers was a smart-alec dandy. "Thinks he's a lady killer," Kittie said scornfully. When Nellie Banghart had the whooping cough, Frank made fun of her whoops and when she had another spasm of coughing, she ran to him and coughed right in his face. Then, when Frank was suffering from the whoops he had caught from her, every time he would get his breath from coughing he would say, "Damn Nellie Banghart!"

Mr. McCumber was deputy sheriff. "Too big for his britches," my Daddie said, but it was because he was young, and the weight of authority swelled him a bit. He had a peculiar waggle to his hind foot when he danced, and John Smoot, the young rascal, would get right behind McCumber, where he couldn't see John, and imitate his step so successfully that it kept the boys and girls in an uproar. And, in contrast, I remember how smoothly and delightfully Ferd Nellis moved his feet dancing a schottische. He wore some sort of dancing pumps and that was unusual in a country full of cowboy boots. The schottische of that day was a smooth and beautiful dance—not the Hooligan Hop they have made of it now. (173)

Then we found Mr. Jackson, the bee man, on the trail going down to Prescott and stopped to talk and visit with him in his little cabin by the road. He didn't see many people and enjoyed company. He told us that people said "Jackson's bees have to wear green goggles to find something to eat there," but they did find something, for we bought a quart of honey from him and took it on to Prescott. We never did eat all that honey, though. It had a last lingering bitter flavor that came from something those green-goggled bees found on that mountainside. (175)

Some years later—when Mrs. Bush was in the Legislature—I heard her tell an audience (at the old Museum on Van Buren Street) some of her river experiences. On one occasion, when it was very stormy and the river very high and rough, Nellie had a preacher aboard her craft. He was very frightened and on his knees all the way across praying for safe deliverance. When they finally reached shore, he rose from his knees in great relief and thanked God so loudly and fervently that Nellie was a little peeved. She thought he ought to have given the pilot a little of the credit—for, said she, "I was running that ferry boat." (177)

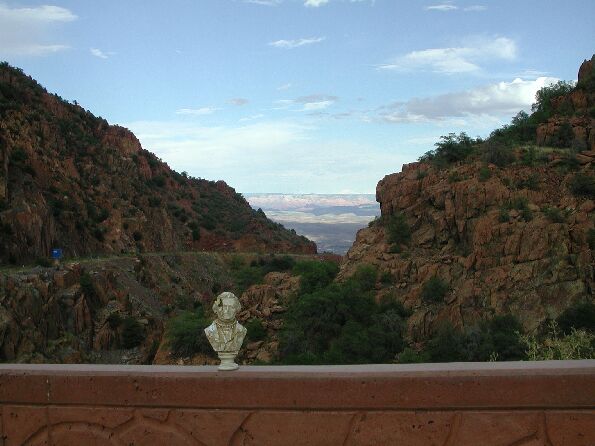

Jerome, the town, was and still is a remarkable place—even though it is now a ghost town—and the approaches to Jerome are almost as astonishing as Jerome itself. Up and down a comer of Mingus Mountain on the Prescott side or up the hill from Cottonwood and Clarksdale on the Oak Creek side—either one would put all roller coasters in the shade for thrills. My first sight of Jerome came when we were visiting a cousin of John's in Prescott. Her son, Harold EIdridge, worked in the mine and we all went up from Prescott to visit Harold and his wife.

On the road up from Prescott, after you had negotiated all the loop-the-Ioops on Mingus Mountain and come right to the shoulder of the hogback that Jerome city was built on, you suddenly turned a corner and there was a low stone wall right in front of you.

If you didn't stop or go on around the sudden turn, you would have run into the wall—and over behind the wall there was nothing. It was awfully sudden and surprised me considerably the first time, but I got used to it. There was a bit of room to pull up by the wall and look; John delighted in taking people to see Jerome, and he always maneuvered his sightseers around that corner while he had them looking somewhere else; then he waited to see them gasp and grab their hats. Next to jumping right up to the edge of the Grand Canyon, I don't think I have ever seen anything more startling. (187)

It is strange what inconsistent creatures these second coming people are. They want to come to this wide-open country because it is different. They like the wide-open spaces, but as soon as they discover them they go perfectly batty about how wide the spaces are; they work frantically to fill it full of people. They want to come to this country because it is different—but right immediately they start making it over into something just like the place they came from. (202-3)

There is another little item I have to charge off to Progress, and that is what it has done to our Salt River. Time was when the river bottoms of the Salt and Gila were beautiful places—where there were rocks and ripples visible, many pretty pebble beaches, and cottonwood trees growing on the banks of a beautiful stream. We used to go fishing in the Salt and to have picnics on the river bank—and I have stood on the tongue of land where the Salt and Gila came together—the confluence of the Gila and Salt, if you please.

Confluence is a beautiful word; it is much sought after and used by modern writers who like pretty words to describe the joining of rivers. Our Arizona Highways Magazine says it is published "a few miles north of the confluence of the Gila and Salt." On the south side of the river and just west of this confluence of rivers stands the little mountain that is the starting point for all surveys in Maricopa County. It is the Gila and Salt River Base Meridian; I became familiar with that name long before I ever saw this butte. In Mr. Cassidy's office in Phoenix I wrote those words, or the abbreviation, G. & S.R.B.M. on many a document.

Well, the Base Meridian mountain is still there, but the "confluence" has gone to glory. Salt River no longer "conflows." It doesn't even flow. In plain English, it is dry. Progress—exploitation—often synonymous—have taken an the water from Salt River, and there can be no confluence with out two streams. Now, with little water in the Gila and none in the Salt, the river bottoms are choked with the jungle of salt cedars (tamarix gallica) imported here by some unforgivable creature. Maybe we can lay the bringing of these indestructible plants here to some kind of progress.

Progress, you know, can be good or bad—though real estate agents will never agree with that last word, but we must remind them that even as a city's growth can progress, so can a war—or a case of measles. (203-4)

I am glad that, at least, this one fine tree is here to show us what the mesquite forest may have looked like if we had been here to see it before progress came along and cut all those beautiful trees and tore up the earth to make farms. We (people, not me) came to this country and took it away from the Indians and then spoiled the country. "Spoil," says the dictionary (and that word hasn't yet progressed to mean something nice), is to rob, to plunder, to strip of things considered as prizes by the plunderers. Progress, they call it, and it seems that progression of some sort must go on—but most of it is awfully wasteful. (208)

|