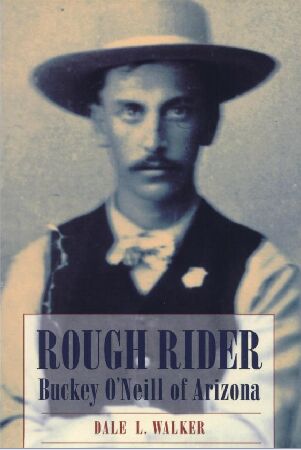

Buckey O'Neill: The Story of a Rough Rider

Dale L. Walker (1975)

ln the fall of 1880, just a year after Buckey arrived in Phoenix, President Rutherford B. Hayes stopped over in the little town of Maricopa, south of Phoenix, to talk to some Apache chiefs. The President's traveling companion, General William Tecumseh Sherman, overheard a remark that all Arizona needed was less heat and more water. "Huh!" snorted the general. "That's all Hell needs!"

In 1870, the Territory's countless miles of primitive desert and uncharted mountain country had been carved into eight enormous counties: Mohave and Yuma on the western side; Yavapai, largest of them all, to the north, containing the territorial capital at Prescott; Apache, Pinal, Casa Grande, and Pima (with Tucson as county seat); and Maricopa, shaped roughly like a six-shooter pointed eastward with Phoenix, its county seat, at the trigger. (2)

Gambling hall habitues of the day had a neat phrase for it—"bucking the tiger"—and William O. O'Neill, only a few months in the Territory, and only a few dollars in his pocket, won the appropriately gutsy nickname that soon was recognized throughout the West. When he became an officeholder, his official letters always bore the signature "W. O. O'Neill," but when he wrote to friends, it was always "Buckey." (5)

Phoenix in the 1870s had a large share of stage robbers, claim jumpers, cattle thieves, and miscellaneous gunmen, high rollers, punks, drunks, and drifters—far more than any one man, including the redoubtable Henry Garfias, could handle alone. Even hangings, half a dozen at a time, could not thin the ranks of the criminal element. A selection of headlines in Buckey's own Herald, gathered under the general heading, "Cavalcade of Crime," gives an indication of the work cut out for any Phoenix lawman:

A BLOODY WEEK IN PHOENIX ENDS WITH A GRAND NECK TIE PARTY

SIX PERSONS LAUNCHED ON THEIR JOURNEY DOWN THE DARK RIVER

JOHN LA BAR STABBED FATALLY BY A DRUNKEN RUFFIAN

JESUS FIGARO PISTOLED ON THE GILA AND ANOTHER MEXICAN KNIFED AT SEYMOUR

MCCLOSKY AND KELLER HURRIED HELLWARD AT THE END OF A ROPE (5)

On March 15, 1879, O'Neill wrote a carefully phrased letter to the secretary for Arizona Territory in Tucson, stretching the truth a bit in the first few words, but seriously determined nonetheless: "I am a young lawyer, also a practical printer and am desirous to reap whatever advantage that may accrue by taking the advice of Horace Greeley and seeking a new home and better fortune in the land of the setting sun .... " (11-12)

Everybody knew about Tombstone, and nowhere was it better advertised than in the saloons and gambling parlors. In those places grubby prospectors, tongues oiled, spun fantastic tales of silver mines named "Lucky Cuss" and "Tough Nut," with streaks so pure you could push a double eagle against them and leave an impression clean as a die. (13)

Shieffelin's initial mine and subsequently the town were named by their founder who recalled asking a soldier what he might find out in the blistering-hot Dragoon Mountain country. The reply was "Your tombstone." (14)

Buckey spent a day or two leaning on his meager savings, distinctly un-Mammon-like, and getting a feel of the town. Tombstone definitely could be felt. Almost every road and path, particularly the well-traveled Fremont Street, were covered with several inches of a lime-like powder that stirred in low clouds at the slightest movement, clinging to boot and trouser leg. This fine dust blew skyward in the breeze or in the swirl of hooves and wheels, in enormous stifling and blinding clouds. (14-15)

Tombstone, in fact, had much to offer the lawbreaker; it attracted stage robbers, cattle rustlers, con artists, murderers and waylayers like a lodestone. The town was isolated and insulated from the law: "For isolation," one authority said, "it was as good as the Big Bend Country, and it did not have the drawback offered by the Texas Rangers." Furthermore, it was within easy riding distance of such notorious gang hideaways as Galeyville and Charleston, where nests of "cow boys," as the southeastern Arizona badmen were called, enjoyed virtual immunity from the badge. (17)

Not many months after launching Hoof and Horn, he was able to present the Legislature with a thumping $6,500 printing bill.

At almost any other time, the territorial legislature would have gagged on such a debt, but the ultraliberal (especially in spending) Thirteenth Legislative Assembly, popularly called "the Thieving Thirteenth," paid it without a whimper. After all, what was $6,500 when the city of Phoenix was given $100,000 for an insane asylum, Tempe an appropriation for a normal school, Tucson $25,000 to begin a university, Florence $12,000 for a bridge? The Legislature itself allowed $50,744 for its own operating expenses, a sum $46,744 in excess of what it was legally entitled to spend.

Buckey not only collected his printing bill but took a further step in dunning the legislature for the five hundred dollars in stenography fees he had failed to collect three years earlier in Globe. (35)

Buckey was a political novice, a maverick, and unpolitically, amusingly blunt about every thing. He seemed to think "candidacy" had something to do with "candid."

In announcing for the office, Buckey gave the Flagstaff Champion this statement:

No "anxious public," the "solicitation of many friends," nor "the wishes of many prominent citizens" have made the slightest effort to "bluff" me into doing it. To be frank, it is not a case where the office is wearing itself out hunting for a man—not much! Here it is the man wearing himself out hunting the office, and rustling like Sheol to get it, for the simple reason that it is a soft berth, with a salary of $2,000 per annum attached. While in the way of special qualifications, I have no advantage over seventy-five percent of my fellow citizens in the County, yet I believe I am fully competent to discharge all the duties incident to the office in an efficient manner, if elected. If you coincide in this opinion, support me, if you see fit. If you do not, you will by no means jeopardize the safety of the universe by defeating me. (49)

This region became a major farming locale in early Arizona because of the availability of water. Jack Swilling, the Confederate deserter and outlaw, had organized an irrigation company in the area in the 1860s and ten years later a population of more than three hundred had been attracted to the place then called "Pumpkinville," later to be given the more dignified name of Phoenix. (58)

On this particular occasion, Buckey said: "You know what I would like to do, Mose? I would like to take fifty thousand dollars and invest it at four percent and then go back to Washington and just simply live at the Library of Congress and study about socialism."

"You know, Buckey," Haziltine responded, "fifty thousand dollars at four percent would only bring you two thousand dollars a year and you would only get one thousand of that."

"Why is that?" said Buckey, his roll-your-own bouncing on his lip.

"Well, being a socialist you would have to give me half of it."

Buckey's fingers came to his mouth in a "V" and removed the butt. With a grin he answered, "Mose, I only divide what I haven't got." (60)

About five miles south of the Diablo Canyon station, the four men divided the loot into even piles. Smith got the diamond earrings and, after removing them from their settings, put the loose stones into his pocket. He forgot about them and later scraped the stones out of his pocket and put them with tobacco crumbs into his pipe. When he knocked the ashes out on the heel of his boot, the diamonds were lost. (69)

The terrible event of February 22 was long remembered in Yavapai County. For years afterward, the flood was used as a convenient conversational explanation for the question, "I wonder what ever became of old so-and-so?" The common response: "Well, I guess he went down the river." (80)

Prescott saloonkeeper Bob Brow, fulfilling his vow to do something for the "boys," came up with a mascot for the troopers—a feisty mountain lion named Florence. (131)

The adjutant general, R. Allyn Lewis, proposed a toast to the assembled officers: "Now we drink the soldier's toast—death or a star!" Buckey jumped to his feet and, holding high his glass, responded, "Who would not gamble for a new star?" To some, Buckey's meaning was clear; to others it indicated that the Prescott mayor hoped to return home at least a brigadier general. (132)

Some of the lean and sunbaked Westerners were known by nickname only: "Cherokee Bill," "Happy Jack," "Smokey Moore," "Rattlesnake Pete," "Tough Ike," "Prayerful James" (one of the most sulfurous and inventive cussers in the regiment), "Metropolitan Bill," "The Dude," and "Sheeny Solomon," the latter a red-haired Irishman. (137)

The thought of having to stay in Tampa for any length of time gagged not only the Rough Riders but every other trooper and infantryman there. Dysentery and fever were beginning to spread, and fresh fruit and vegetables were getting scarce. One New York recruit expressed his disgust with the place telling an eager reporter that on his first day in camp he had been bitten by mosquitos, stung by a tarantula, felt a touch of malaria, ran his bayonet into his hand, sat on an ant's nest, stepped on an alligator, found a snake in his boot, and felt "like a dirty deuce in a new deck." (151-2)

Buckey, during the voyage to Cuba, got to know and like the young acting surgeon of the regiment, Dr. Robb Church, a former Princeton football player destined to win the Medal of Honor in the forthcoming campaign. Roosevelt, with amazement, later recalled Buckey and Dr. Church talking over "Aryan root-words together and then sliding off into a review of the novels of Balzac." (154)

There were no other human casualties in the Daiquiri landing, but six horses died trying to swim ashore. Many of horses and pack animals had been thrown overboard into the terrible, pounding surf as the simplest and most expedient way of getting them ashore. When a group of cavalry mounts began to swim from the ships toward the open sea, a quick-thinking bugler on the beach blew the proper call, and the horses wheeled and headed for shore. (157)

"Brodie had not the least idea that he could be hit by a mere Spaniard. I shall never forget his expression of amazement and anger as he hopped down the hill on one foot with the other in the air, before he fell. He came toward me, shouting, "Great Scott, colonel, they've hit me!" (162)

As Buckey paced in front of his waiting troopers, occasionally stopping long enough to twist a new cigarette from borrowed tobacco, Lieutenant Woodbury Kane, whose Troop K was deployed nearby, warned his superior officer to take cover. But, like Alex Brodie, Buckey felt he owed his men the confidence of his own fearlessness and contempt for the Spanish soldier while they were under fire.

Buckey's disdain for the Spanish soldier, and Brodie's, was an attitude endemic in military as well as civilian ranks. Buckey more than once had said, half-jokingly, "The Spanish bullet isn't molded that will kill me." At about ten o'clock the morning of July 1, 1898, Buckey strolled over to talk with Captain Robert D. Howze, an aide to General Sumner. The conversation ended abruptly a few minutes later as a Mauser bullet, fired aimlessly by the enemy, struck Buckey in the head with a chilling "splat." Captain O'Neill crumpled to the earth without a sound. (172-3)

Private Jesse Langdon of Woodbury Kane's K Troop saw precisely what happened and recalls vividly:

"I was not a member of his troop, however I actually saw him die as I was not fifty feet from him, and the attention of everyone near him was called to him by the fact that everyone was telling him to `lay down' ... at that moment he was hit in the mouth, the bullet coming out the back of his head."

Private Arthur Tuttle of Safford, a member of Buckey's troop, also heard the murmur of Buckey's and Howze's conversation. Tuttle recalled that he was staring straight at Captain O'Neill when he saw his commander stiffen and collapse without a sound. "I heard the bullet," Tuttle later recounted; "you usually can if you're close enough, you know. It makes a sort of 'spat.' He was dead before he hit the ground." One William Pulsing told a New York Times reporter two months afterward that he too was an eyewitness to the tragedy: "Suddenly a Mauser bullet struck him squarely in the mouth," Pulsing said, "going in so evenly that his teeth weren't injured. He fell to the ground at once, and I and a man named Boyle who was afterward killed in battle, picked him up and carried his body to the rear. He died there in a few seconds." (174-5)

"... When I passed by his body," [adjutant Tom] Hall wrote, "... and stooped to raise the hat from his poor head, I couldn't read any satisfaction in the glazed eyes that looked back at me. He was of the type whose soldierly fault is their useless bravery—a knight of chivalry in the dirty brown jeans of a Rough Rider." (175-6)

Buckey O'Neill was the only regimental officer killed among the Arizona volunteers. Sixty-seven days before he died, the war had been declared; forty-two days after his death, the war ended. (177)

WILLIAM OWEN O'NEILL

Mayor of Prescott, Arizona

Capt. Troop A, First U.S. Vol. Cav. Rough Riders

Brevet Major

Born Feb. 2, 1860

Killed July 1, 1898, at San Juan Hill Cuba

"Who Would Not Die for a New Star in the Flag." (180)

. . . a foolish epitaph to match a useless death.

|