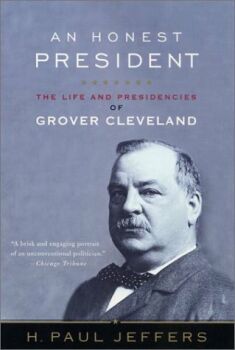

An Honest President (2000)

by H. Paul Jeffers

Buy this book

-

One day, in the tradition of men who have discovered happiness in married life, Oscar asked Grover when Grover might be expected to find a wife. Grover looked smilingly at [eight-year-old] Frances and replied, teasingly, "I'm only waiting for my wife to grow up." When one of Grover's sisters asked whether he had ever thought of marrying, he replied, "A good many times; and the more I think of it, the more I think I'll not do it." (37-8)

-

When the convention nominated David B. Hill ... as Grover's running mate ... Grover told him in a congratulatory letter, "Now let us go to work to show the people of the State what two bachelor mayors can do." (55)

-

Official acceptance of the gubernatorial nomination took the form of a letter to the state party chairman, Thomas C. E. Ecclesine. It was a blunt declaration of war on those who would pervert public affairs to private ends. (56)

-

"Had Grover Cleveland been a politician, with the record of a spoilsman behind," wrote his biographer Robert McElroy, "his promises would mean little. They might have deceived a few of the simple, disgusted a few of the honest, caused mirth to a few other spoilsmen, and thus fulfilled their intended mission; for Americans had long since learned that, as the devil can quote Scripture, so the most dangerous type of demagogue can sing of ideals in false notes not easily distinguishable from true. But Mr. Cleveland had already put into practice the ideals which he announced, and Republicans bent on reform rallied to his support with an enthusiasm equal to that of his Democratic followers." This revolt of political dissidents from both parties into a movement for reform would later be given a name by a colorful newspaperman, Charles A. Dana.... He called them Mugwumps. (57)

-

"I shall have no idea of re-election, or any higher political preferment in my head, but be very thankful and happy I can serve one term as the people's Governor." (59)

-

The next noon, a curious audience braved the cold and clear weather with a brilliant sun glinting on the snowy grounds of the capitol not only to see him in the flesh and mark what their new governor had to say, but to hear his voice for the first time. They found it ringing and clear, and many marveled that he spoke without a script or notes. (64)

-

In an age of long speeches, his inaugural address was so brief as to provide few clues to the future. It ran seven paragraphs and less than five hundred words without clarion calls to greatness. No galvanizing words. No indelible phrases. Only a call for "vigilance on the part of the citizen" and a summons to be "contributors to the progress and prosperity which will await us." (66)

-

He chose to sound notes which had served him well as mayor. He appealed to the legislature to keep "a jealous watch of the public funds" and to refuse to "sanction their appropriation except for public needs." To this end he demanded an abolition of "all unnecessary offices . . . and all employment of doubtful benefit." And he called for "absolute fairness and justice" when exacting "from the citizen a part of his earnings and income for the support of the government." (66)

-

The new governor exhibited a work habit which had been noted by his admirers (and detractors) when he practiced law, as assistant district attorney and sheriff, and during his term as Buffalo's mayor. Whatever action he took was the consequence of long hours spent studying the issue, reading and parsing every word and phrase, careful weighing of pros and cons, and presentation of a laboriously worked out explanation of his rationale. (68)

-

Most who took advantage of the governor's availability came seeking jobs and justifying their requests by service to the party, only to be greeted by steely blue eyes and the words, "I don't know that I understand you." (70)

-

His answer to anyone who sent him proposed legislation he considered not in the public interest was a veto couched in language which called attention to shoddy thinking and sloppy draftsmanship, and frequently to the fine print and clauses that he deemed to be attempts to mask a raid on the treasury. (81)

-

Again left with a pile of legislation to be read, studied, weighed, and signed or not, the governor ... sent a note of regret ... in which he said he had such an "economy of time I am afraid the night will not be long enough to do all I have at hand. Need I say any more -- except to assure you that `It's fun to be governor'?" (91)

-

[After it was revealed that Cleveland had once fathered a child out of wedlock:]

In a state of alarm, if not panic, Cleveland's friend Charles W. Goodyear wrote him to ask what the party should say. Grover replied by telegram on July 23: WHATEVER YOU DO, TELL THE TRUTH. (108)

-

Uncomfortable and embarrassed by their tactics, Grover Cleveland declined to participate in character attacks on Blaine. When presented with papers which purported to be extremely damaging to Blaine, he grabbed them, tore them up, flung the shreds into the fire, and decreed, "The other side can have a monopoly of all the dirt in this campaign." The following passage from Robert McElroy's two-volume biography of Cleveland may seem extravagant in its praise, but it is nonetheless a true portrayal of his character in the heat of the campaign:

Unskilled in sophistry and new to the darker ways of national politics, Grover Cleveland faced his accusers, his slanderers, and his judges, the sovereign people, conscious of the general rectitude of his life, and courageously determined to bear the burdens of his sins in so far as guilt was his.

-

"Imagine a man standing in my place, with positively no ambitions for a higher position than I now hold, and in constant apprehension that he may be called to assume burdens and duties the greatest and highest that a human being can take upon himself. I can not look upon the prospect of success in this campaign with any joy, but only with a very serious kind of awe. Is this right?" (116)

-

Concerning "a fine Newfoundland dog" which had been sent to him as a gift by an admirer, William J. Leader, he responded, "I hope you will not deem it affectation on my part when I write you that I am very averse to the receipt of gifts -- especially in the relation of strangers which you and I sustain to each other. . . . The acceptance of presents of value which could involve an obligation, I should deem in my present position entirely inadmissible." The dog was returned the next day by express at Grover's expense. (122-3)

-

Oath taken, the twenty-second president of the United States stepped to the podium to deliver his inaugural address, and to secure a place in the history of such speeches by making it without a manuscript.... "Preparing every public utterance with the greatest of care, not only as to word, phrase, and sentiment, but as to punctuation," noted George F. Parker, "he had the rare gift, with only the slightest effort, of so memorizing his own writings that he could deliver an address of an hour in length without loss or change of a word." (134)

-

The feat of memorization is all the more remarkable because the printed text of the address in a book of Cleveland speeches runs more than five pages. To those who knew the speaker and his record in public office, its keynote was familiar: "The people demand reform in the administration of the government, and the application of business principles to public affairs." In that enterprise, he said, he would give the nation economy, isolation from foreign entanglements, an executive branch "guided by a just and unrestrained construction of the Constitution, a careful observance of the distinction between the powers of the federal government and those reserved to the State or to the people." (135)

-

There was no White House "visitors' center" with metal detectors to screen those who came. No tickets. No eagle-eyed Secret Service agents in uniforms and plain clothes scanned the line of callers for the potential assassin. Nor was there an electronic security system, a tall iron fence turning a presidential residence and offices into a "compound," or sentries at gates, assorted color-coded passes to be displayed on clothing, antiaircraft and missile defenses on the roof, sharpshooters and barriers closing Pennsylvania Avenue and other surrounding streets to traffic. A citizen was free, if he or she desired, to walk right up the lane or cross the front lawn and up to the front door unchallenged. The white mansion stood alone, unextended by east and west wings to accommodate staffs of the president and the first lady. No swimming pool. No room set aside for reporters. No photo ops. Not even a press secretary. (137)

-

Grover shocked them and the gold-standard defenders on Capitol Hill with what amounted to a shrug of the shoulders. He said, "I believe the most important benefit that I can confer upon my country by my Presidency is to insist upon the entire independence of the executive and legislative branches of the government." (159)

-

... the presidential pen was wielded to veto a measure popularly known as the Texas Seed Bill. It authorized federal assistance in the form of an authorization for the Commissioner of Agriculture to distribute $10,000 to help farmers in Texas who had been hit hard by a drought. The money was to finance the buying of seed. Grover found no basis in the Constitution for such congressional largesse. He said he did not believe "that the power and duty of the General Government ought to be expended to the relief of individual suffering which is in no manner properly related to the public service or benefit." (194)

-

[Congress] had adjourned in March having done nothing to deal with a problem which was of increasingly grave concern to Grover and his advisers in terms of the continued health of the nation's economy. The federal government had too much money. At the end of the fiscal year the surplus in the Treasury was nearly $94 million. Most of that was the result of collection of high tariffs. (199)

-

Grover grumbled to a friend, "What is the use of being elected or re-elected unless you stand for something?" (200)

-

[From Cleveland's third State of the Union address:] "When we consider that the theory of our institutions guarantees to every citizen the full enjoyment of all the fruits of his industry and enterprise, with only such deduction as may be his share toward the careful and economical maintenance of the Government which protects him, It is plain that the exaction of more than this is indefensible extortion and culpable betrayal of American fairness and justice. This wrong inflicted upon those who bear the burden of national taxation, like other wrongs, multiplies a brood of evil consequences. The public Treasury, which should only exist as a conduit conveying the people's tribute to its legitimate objects of expenditure, becomes a hoarding place for money needlessly withdrawn from trade and the people's use, thus crippling our national energies, suspending our country's development, preventing investment in productive enterprise, threatening financial disturbance, and inviting schemes of public plunder.... It will not do to neglect this situation because its dangers are not now palpably imminent and apparent. They exist none the less certainly, and await the unforeseen and unexpected occasion when suddenly they will be precipitated upon us.... The simple and plain duty which we owe the people is to reduce taxation to the necessary expenses of an economical operation of the Government and to restore to the business of the country the money which we hold in the Treasury through the perversion of governmental powers." (201-2)

-

As analysts of the outcome concluded that he'd lost [the presidency] because of his stand on tariffs, Grover told a friend he had no regrets. "I would rather have my name to that tariff measure," he said, "than be President." (222)

-

Recalling that advisers and friends had asked him not to send Congress the tariff message, he said, "They told me that it would hurt the party; that without it, I was sure to be re-elected, but that if I sent that message to Congress, it would in all probability defeat me; that I could wait till after the election and then raise the tariff question. I felt, however, that this would not be fair to the country; the situation as it existed was to my mind intolerable and immediate action was necessary. Besides, I did not wish to be re-elected without having the people understand just where I stood on the tariff question and then spring the question on them after my re-election. Perhaps I made a mistake from the party standpoint; but damn it, it was right. I have at least that satisfaction." (223)

-

The loss of the election was not a personal matter, Grover said to a reporter.... "It is not proper to speak of it as my defeat. It was a contest between two great parties battling for the supremacy of certain well-defined principles. One party has won and the other has lost -- that is all there is to it." (224)

-

"The animating spirit of the Administration was administrative reform," [Cleveland] said.... "a wholesale ventilation and stirring up of all the branches of that service, the lopping off of useless limbs, the removal of the dead wood..." (225)

-

Some newspapers claimed that he left the White House with a "private fortune." But he exited in no better financial shape than on the day he'd entered. Asserting that "a man is apt to know too much in my position that might affect matters in the least speculative," he had not played the stock market. (225)

-

And on March 4, a day of thunder and heavy rain, as her husband and the incoming president departed in a carriage for the inauguration ceremony at the Capitol, [Frances Cleveland] said good-bye to the White House staff. Each received an autographed picture. But as she got into a carriage to go to the Capitol, she voiced a final order for one of them, Jerry Smith. "Now, Jerry, I want you to take good care of all the furniture and ornaments in the house and not let any of them get lost or broken, for I want to find everything just as it is now, when we come back again." Puzzled, Smith asked when that might be. With the smile that had enchanted official Washington and captivated the press, she replied, "We are coming back just four years from today." (227-8)

-

The Cleveland fiscal policy was a three-legged stool: opposition to federal paternalism (the government does not support the people); the gold standard; and reduction, if not elimination, of protective tariffs, which he believed hurt the American consumer while provoking tariff retribution by foreign governments against American exports. (285)

-

On the retirement of presidents he said, "Something ought to be done. As it is now, nothing seems to be dignified enough for them. Now there was Harrison; he went into law. The first time he got up to argue a case in court everybody laughed; it seemed so queer. I know how it is. I went back to law myself when I left Washington the first time. I walked into supreme court and there on the bench sat two judges I had appointed myself. No, it doesn't do . . . So a fellow has to remain a loafer all the rest of his life simply because he happened to be president. It isn't right. It isn't fair." (325)

-

Grover Cleveland spoke again, posthumously, in the September 1908 edition of American Magazine: "A sensitive man is not happy as President. It is fight, fight, fight all the time. I looked forward to the close of my term as a happy release from care. But I am not sure I wasn't more unhappy out of office than in. A term in the presidency accustoms a man to great duties. He gets used to handling tremendous enterprises, to organizing forces that may affect at once and directly the welfare of the world. After the long exercise of power, the ordinary affairs of life seem petty and commonplace. An ex-President practicing law or going into business is like a locomotive hauling a delivery wagon. He has lost his sense of proportion. The concerns of other people and even his own affairs seem to small to be worth bothering about." (341-2)

-

Cleveland's papers [were] packed into rough wooden boxes, without systematic arrangement, the important and unimportant thrown together.... Practically every letter, message, proclamation, and executive order, even the publicity notices and the successive copies of addresses with revisions, had been done in Grover's hand. (346)

-

In 1968 Rexford Guy Tugwell published a Cleveland biography asserting that Grover's "uncompromising honesty and integrity failed America in a time of crisis." A former member of Franklin D. Roosevelt's "brain trust," former governor of Puerto Rico, professor of political science at the University of Chicago, and scholar at the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions, Tugwell wrote:

Cleveland ... was destroyed -- or his power and influence were -- by his own strength and virtue. . . . He would do nothing and would allow nothing to be done that he or any other might profit from. He would give no favor and accept none, except in the public interest. In the sense understood by all Americans, he was a man of conscience. . . . Above all, he was honest. That there was a higher honesty for governments and their Presidents he never comprehended.

This assertion that there were two standards of honesty -- one for individuals and one for governments and presidents -- seems astonishing, except that it was made by a New Deal liberal in a year when the very foundations of American government and society appeared to be staggering.... Tugwell also faulted Grover for not being a visionary. He opined, "Democracies must have leaders who are the people's prophets and who act as their mentors. A prophet must see ahead and turn the people's minds to the future. A mentor Cleveland was -- a stern and determined one. A prophet he was not."

This criticism of Grover was attacked two decades later by Richard E. Welch Jr. in The Presidencies of Grover Cleveland. He wrote, "Tugwell's censure appears to be not only harsh but essentially ahistorical. If Cleveland is to be damned, it cannot be for his failure to imitate Franklin Delano Roosevelt." (348-9) #

-

A suggestion to Grover that the people of the United States needed a prophet to lead and teach them, and that the person was himself, would have left him flabbergasted. He believed that the futures of individuals and nations were grounded in what they did in the present.... The role of a president was to see that government was not an obstacle and that those who governed understood that they were servants, not masters, and that public office is a public trust. The people supported the government -- led it -- not the other way around. (349)

-

Americans learned was that in the handling of the somewhat similar sex scandals, [President Bill] Clinton had failed to measure up to Grover in one important aspect. In 1884 Grover had admitted the truth of his failing and ordered his campaign staff to do the same. (351)

-

Had Grover been able to materialize in the era of Clinton, what might he have thought?... What of spinmeisters, pollsters, the use of focus groups to decide government policy, war rooms, dirty tricksters, private detectives hired to dig up negative information on opponents, paid political consultants, photo ops, press leaks? What about the parsing of words and twisting of the English language so that even the meaning of "is" could be questioned?

Grover also would have discovered about the Clinton era of politics and government and the press, as Gail Collins wrote in 1998 in Scorpion Tongues: Gossip, Celebrity and American Politics, that "once in office, it was natural that Clinton would become a trailblazer in eliminating the public's sense that there were certain things you didn't say about a president in public. His willingness to answer a question on an MTV forum about what kind of underwear he wore was the first stunning breach of the old propriety."

... [Grover] would not be surprised to find a president in the glare of sensation seekers. He would disapprove of a citizen asking such a question. And he would have been appalled that a president of the United States not only chose to answer it, but found it amusing to do so. In his beloved United States of America at the dawning of the third millenium, he would realize that he'd returned to life as a man in a fur coat in July. (352-3)

Notes

% Had Cleveland foreseen that the Washington government would use the Interstate Commerce Commission to justify every sort of intrusion into the lives of citizens and businesses, it is inconceivable that he would have signed it even with a knife at his throat. (Back)

# One has to wonder whether Tugwell had any connection at the U. of Chicago with Leo Strauss, whose ghost hovers over a Bush administration that shares Tugwell's contempt for honesty and embrace of an ethical double standard. [Back]

|

![]()

![]()