Hemp, Commerce, and Freedom

(First published in Planet Magazine, jan1996)

If you heard about a plant that could help supply the

basic necessities of life — food, shelter, and clothing-

-and could cheaply and easily serve as a non-polluting

alternative to many chemical and wood-based products

and replace fossil fuels altogether, what would you do

with it? For anyone of average intelligence, the

obvious course of action would be to make use of the

plant's many benefits in any way possible, as soon as

possible. Unfortunately, for those of subnormal

intelligence — which is to say, politicians — the obvious

course of action is the opposite of the obvious one.

Though it may sound too good to be true, industrial hemp may

be the most versatile raw material in the world. As a kid I

used to be amazed by the advertising on the sides of Arm &

Hammer boxes, which listed hundreds of uses for baking soda.

Industrial hemp is even more versatile, with over twenty-

five thousand known uses. Aside from its more well-known

uses, such as rope, paper, and clothing, there is hemp ink,

hemp soap, hemp shakes, hemp burgers, hemp cheese, even hemp

breakfast cereal.

It is almost unbelievable, then, that our nation's leaders

should forbid the growing of a such a useful plant, even

more so when you know that hemp had the enthusiastic backing

of our nation's original leaders. George Washington and

Thomas Jefferson, for example, couldn't say enough about the

benefits of hemp, growing it themselves and encouraging

others to do the same. (Hemp activists like to remind

people that the Declaration of Independence was originally

drafted on hemp paper.)

There was no official interference with hemp until the

beginning of the era of big government. After the repeal of

Prohibition, the Federal government's failed attempt to do

away with alcohol, the Feds immediately repeated their

mistake, outlawing marijuana in 1937. Unfortunately,

marijuana's downfall took industrial hemp along with it, in

spite of the fact that industrial hemp contains less than 1%

of THC, the psychoactive ingredient contained in marijuana —

you could smoke industrial hemp all day, but you might just

as well smoke the morning paper. Politicians not being

known for fine distinctions, however, this country has been

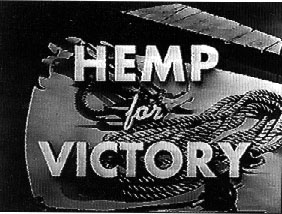

deprived of hemp's benefits ever since (except for a short

period during World War II when the government actually made

propaganda films as part of the "Hemp for Victory!" campaign

to persuade farmers to grow hemp).

Today, anyone can legally make, sell, and buy hemp products

in the U.S., but no one can legally grow it here. American

manufacturers are forced to import hemp from other

countries, an unnecessary outflow of U.S. dollars. "In the

past few years, the industry has been exploding faster than

importers can keep up with the demand," says Ted Kaercher,

owner of Headquarters, a retailer of many hemp products. "In

fact, U.S. Customs just raised the quota for importing hemp

because distributors were running out of their allotted

supply within three months of the calendar year."

Marjorie Holmes, of Everything Earthly, a Phoenix shop that

sells hemp goods, sees the biggest obstacles to hemp

legalization as "the Drug Enforcement Agency and lack of

education." Yet any fears the DEA might have about hemp

being a cover for marijuana are unfounded; even an untrained

eye can easily distinguish a hemp plant from a marijuana

plant. Industrial hemp's complete lack of psychoactive

powers is not of interest to the DEA, however. They seem

more concerned that any move toward legalizing an outlawed

substance would be seen as a blow to the agency's near-

dictatorial powers.

Even so, the states are beginning to fight back. According

to Kathy Trout, of Tucson's Crucial Creations, Kentucky,

Colorado, and California are trying to legalize the growing

of hemp, and tribes on eleven reservations have petitions

pending. The hemp issue is attracting the attention of

people from many different (though often opposed) camps,

including environmentalists, Libertarians, physicians, and

entrepreneurs.

Unfortunately, the effort faces a major stumbling block in

that people commonly think of the hemp legalization activism

as merely a front for disgruntled potheads. Activists often

do a lot to contribute to that image, an image that was

evident at November's showing of Hemp Revolution, a film

by Australian director Anthony Clarke at the Valley Art

Theater. Having run for public office as a Libertarian

myself, I've had my share of contact with marijuana law

reform groups, and I'd rate the film and its accompanying

"hemp fashion show" as a reasonably accurate microcosm of

the hemp legalization effort.

The fashion show featured local hemp activists modeling

clothing made from hemp fabric. There was definitely a

preaching-to-the-crowd atmosphere — there seemed to be about

as many "models" as spectators among the crowd of perhaps

five or six dozen. Anyone who wandered in off the street to

see what the hemp revolutionaries are doing would probably

have gotten the definite impression that a lot of reefer is

what they're doing, because there were pothead stereotypes

aplenty: tie-dyed Deadheads, dreadlocked rasta dudes, and

of course your off-the-rack Cheeches and Chongs. Not the

whole crowd, of course (I saw some clean-cut average Joes,

including some of the event organizers), but enough to

prevent anyone from thinking they'd wandered into a

temperance meeting.

The clothing itself — some made entirely from hemp, others

hemp/cotton blends — seems well-made and fairly stylish, but

many items are decorated with the inevitable pot leaf

designs. Whenever I see that sort of thing I can't help

recalling the dopes in my high school art classes, who used

to draw, paint, and silk screen pot leaves on just about

everything they owned. In ceramics class, they made ceramic

bongs; in plastic shop, they made plastic bongs; in wood

shop, they made stash boxes. It was my junior year before I

finally discovered that Black Sabbath's "Sweet Leaf" was not

our school fight song. I'm always a little less than

impressed, then, when I see someone wearing a pot leaf.

Fortunately, someone had the good sense to emblazon some of

the clothes with the facsimile signature of dedicated hemp

grower Thomas Jefferson — now there's an angle worth playing.

Unfortunately, it's an angle that is underplayed and

overshadowed by stoner stereotypes. The fashion show's

message — for me, at least — was all but drowned out by the

background music, which consisted almost exclusively of

songs about smoking pot by such groups as Cypress Hill,

those Johnny Appleseeds of weed, whose albums are full of

marijuana anthems even less subtle than "Sweet Leaf."

After the fashion show, director Anthony Clarke stepped up

to the mike and played "Waltzing Matilda" and "The Star-

Spangled Banner" by squeezing his hands together (in junior

high we called it hand farting), supplying notes out of

hand's range with a vocal falsetto or bass, as appropriate

(though in such a setting it's hard to imagine what

inappropriate might be). Once again the image problem — I

mean, if hand farts aren't classic pothead entertainment, I

don't know what is. (Speaking of pothead entertainment, the

soundtrack to Clarke's film features veteran burnout Jackson

Browne. I remember hearing a bootleg album of his called

Pipeline, which captured for the ages the special magic of

a Jackson Browne so slammed he couldn't even remember the

words to his own songs.)

Another image problem the hemp effort faces is its perceived leftist

origin. But the hemp issue is not a leftist issue, it is an issue of liberty, and it is both unwise and

strategically unsound to suggest otherwise. Though most of

Clarke's interviewees kept to the subject of the benefits of

industrial hemp (even University of Arizona's Andrew Weil,

who sports a big Southcottian beard like Marx himself), the

Marxist line was represented by longtime goof Terence

McKenna, who characterized hemp as antithetical to

"capitalist, market-based society." If that were the case,

it's hard to see why the Libertarian Party supports its

legalization. The hemp issue is more of a liberty issue

than anything, and that, properly communicated, would give

it an across-the-board appeal.

In his narration Clarke acknowledges that some hemp

supporters may have what he calls "ulterior motives" (though

he was probably talking about recreational pot smokers

rather than Marxists), but most of the audience seemed

distinctly more interested in marijuana than hemp. Of the

many uses of hemp listed in the narration, the only one they

cheered was "inspiration" (illustrated by an old Asian man

puffing on a gigantic fatty). They responded with even more

applause to the scene of a huge effigy of a joint being

carried in procession like a holy image. These aren't the

kinds of images that are going to persuade ordinary people

to support the legalization of industrial hemp, let alone

marijuana. This is bad news for the hemp cause, since hemp

nearly always gets tarred with the same brush as marijuana.

The smart strategy would be to draw a sharp distinction

between the two. The shampoo commercial of the 70s — "With

beer...but don't drink it!" should be adopted and adapted as

the hemp product commercial of the 90s: "With hemp...but

don't smoke it!"

Like the woman selling rabbits in Roger and Me whose sign

"Food or Pet" turned away customers, hemp activists' lumping

together of hemp and marijuana is like a sign saying

"Clothes or Pot" — it alienates people whose attitudes toward

marijuana have been formed by government and media

propaganda. The chances for the legalization of hemp will

be much better if activists forget about marijuana, at least

for the time being, and emphasize the environmental and

utilitarian benefits of hemp, which are many.

Do people want to save trees? Tell them that hemp could

completely replace wood pulp in the making of paper,

cardboard, and particle board, leaving more of the world's

forests intact. In addition, hemp grows at an extremely

rapid rate ("like a weed," as Hemp Revolution put it,

drawing giggles from the crowd), reaching maturity in only

two months, and is therefore a much more renewable resource

than trees. Are people worried about the contamination of

ground water? Tell them that processing wood pulp into

paper requires toxic chemicals — chemicals which often find

their way into waterways and ground water supplies — while

the making of hemp paper requires none of these chemicals.

Nor do hemp plants require chemicals to fight insects or

even weeds — the plants grow close together and have flowers

at the top of the plant, which shut out light, which chokes

out weeds. Do people want to eliminate automobile

pollution? Tell them that hemp is a cheap and indefinitely

renewable replacement for fossil fuels: hemp fuel burns so

cleanly that automobile pollution could be a thing of the

past. Researchers interviewed in Hemp Revolution said

they ran an ordinary automobile on hemp fuel for 3,500

miles, took the engine apart and found almost no residue.

People not explicitly interested in environmentalism could

be drawn to the hemp cause for utilitarian reasons. The

growing of hemp would create jobs and free us from having to

import such a cheap and easy to grow crop. Tobacco growers

could switch to hemp, get off the Federal gravy train, and

devote their fields to a crop that benefits people instead

of killing them. Hemp is also a great rotation crop because

only the fiber (the stalk of the hemp plant) is harvested,

leaving the flower and root behind to enrich the soil.

Such — rather than pro-pot propaganda — are the kinds of facts

that could convince open-minded people to support the

legalization of hemp. Yet, having lampooned the marijuana

contingent, I don't want to leave the impression that I

favor anti-marijuana laws. The legalization of marijuana

would have its benefits as well. For one thing, our courts

and prisons would no longer be clogged with people whose

only crime is smoking or selling marijuana. One-fifth of

all criminal convictions in this country are marijuana-

related. Obviously the criminalization of marijuana has

been just as big a failure as the outlawing of alcohol

seventy years ago. Laws do not change human desires, and

the desire for alcohol and other mind-altering substances

has proven stronger than fear of punishment. Furthermore,

just as Prohibition virtually created the American gangster,

U.S. narcotics policy has made millionaires of thugs and

criminals of hundreds of thousands of ordinary citizens.

Instead of seeing the foolishness of their position, the

politicians instead waste more of other people's money on

the building of more prisons. And who's out terrorizing the

highways anyway, potheads or hopheads? It's alcohol that's

the killer on the streets, yet the politicians aren't trying

to reinstate Prohibition — so why do they refuse to

decriminalize marijuana?

Everyone under the age of 40 or so has heard plenty of

(mostly health-related) arguments against pot smoking. I've

known lots of potheads in my time, and while I don't know

much about how pot has affected their health, I do know that

most of them tended to become great layabouts and

procrastinators, whose inner life came to consist of having

a few bong hits while watching Kung Fu. Yet arguments

against recreational marijuana use in no way apply to the

medical use of marijuana, which can relieve the nausea of

AIDS patients and keep glaucoma in check. One of the

speakers at the Valley Art show was a man billed as

"Glaucoma Jim," who must ingest large amounts of marijuana

in order to keep his vision. If he should be arrested and

deprived of his marijuana, his doctors have told him, he

will almost immediately become ill and his eyes will fail.

"In three hours I'll be hurling," he says. "In 3 days I

could lose my eyesight."

That the government can without reason withhold medicine

from the sick illustrates the general deterioration of

freedom in the United States. There's no reason — no

constitutional reason, at least — why U.S. citizens should be

denied the right to choose clean hemp fuel instead of

polluting oil products (you don't suppose the giant oil companies

have a vested interest in throwing their massive lobbying weight

against the legalization of hemp, now, do you?) or chemical-free hemp

building materials and paper products instead of forest-destroying,

groundwater-polluting wood products.

The hemp issue's best — perhaps only — chance of success, however, is to

ground itself in the larger issue of freedom. On its own merits it probably

cannot succeed, because under the current system Congress is owned

by bureaucracies such as the ATF and special-interest groups such as the

petrochemical corporations, whose power and wealth would be threatened if

people were free to produce industrial hemp. The success of

the "hemp revolution," therefore, depends the success of a

larger revolution, one aimed at resurrecting and restoring

the freedom once enjoyed by American citizens. Those

politicians who do not educate themselves about freedom

today may tomorrow learn much more than they ever wanted to

know about that most ancient of all hemp products — rope.

© Deuce of Clubs

|