Fair Use: Negativland's Documentary Hypothesis

(First published in Planet Magazine, 04jul1995)

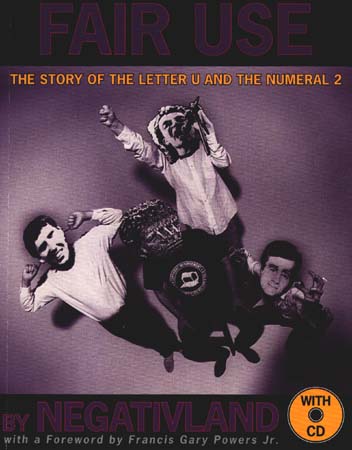

Fair Use is a graphic representation of Negativland's

case in particular and the case for the reform of copyright law

in general.

"Books like ours," says Negativland's Mark Hosler, "are

really going to help in terms of widening the dialogue and

getting people thinking about different perspectives. And the

way things are going to change in this country is through the

courts."

It turns out that Negativland is not as interested in new

copyright law as in enforcing the real meaning of existing

copyright law. "The intent of the copyright law is fine," Hosler

explains. "The idea that you encourage creativity by allowing

people to profit from sharing their ideas or their creations—

that's a great idea. There is a part of the copyright act that is

the "fair use" clause. The reason we called the book Fair

Use was that we really want to direct people's attention to

that little phrase, because the fair use clause has within it the

[right] idea already."

The frontispiece of Fair Use is a reproduction of the

text of the fair use clause of the United States Copyright Act.

"It's saying that if things are being used for some kind of

commentary or criticism or something, that constitutes fair use.

What we want to see happen is an expansion of the definition of

fair use, so that it doesn't have to be just overtly critical, or

commentary, or parody. It could be something that just borders

on surrealism."

Negativland thinks realistic copyright guidelines would

recognize their sound collage efforts as legitimate artistic

expressions. They maintain that what they do is what artists have

been doing for centuries—it's just that advanced technology has

made it easier to do.

"Negativland is actually retrogressive," says Don Joyce, the

band's unofficial art historian. "We are going back to a process

that is very, very old. In visual arts it goes all the way back

to the turn of the century, when collage was invented. Collage

was just taking things from the world around you and pasting them

up together. No payment was made, no permission asked." Some of

our century's most honored artists worked with collage, Joyce

says. "People like Kurt Schwitters used to pick up cigarette

packages off the street and rip the labels off because they were

colorful. Picasso did a lot of it, Braque did a lot of it."

Joyce points out that the same kinds of borrowings—even

outright thefts—have always gone on among classical musicians,

"who used to steal wholesale from other people," not only from

folk music but also from each other.

Modern artists who get caught borrowing can find themselves

in a lot of trouble. John Oswald tangled with Michael Jackson's

record label over a CD cover illustration portraying Jackson as a

nude woman. Oswald was forced to destroy all remaining copies of

the CD. Cases such as Oswald's and Negativland's suggest that it

is more dangerous to tamper with a visual representation than

with sounds; Oswald's "The Great Pretender"—nothing more than a

Dolly Parton record played at different speeds—did not cause any

legal troubles. "Oswald did not put it out as a record with Dolly

Parton's face on the cover and say it's by Dolly Parton—which in

a way is what we did with U2," Hosler says. "[`The Great

Pretender'] is contained within some other work, and it's not

presented in a way that interferes with [Parton's] market at

all."

Market considerations do play some part in Negativland's

copyright position, as Hosler expresses it: "Anything should be

fair game. If you're going to make anything in the popular

electronic media...you should be fair game for being chopped up

and rearranged and used in any way, shape, or form to make

something else. EXCEPT to be used to sell things. That's the one

exception that we personally find just repugnant: that someone

would take something I made and use it to sell something without

my permission."

But couldn't it be said that is exactly what Negativland

does—that they take things others have made and use them to sell

their own records? "Yeah," Hosler admits. "The thing is that the

line is completely blurred between whatever might be sort of fine

art and mass art. I would consider what we do to be mass-produced

fine art."

Do the members of Negativland consider their position on

copyright to be an extreme one? "Given the present paradigm or

situation, I guess it is extreme," says Joyce. "But

internally I don't think it's extreme. It sounds like

common sense to me. Do you want art to be influenced by other art

or don't you? Of course you do. It always has been. Seems to be

the way it works." As Hosler says, "The whole idea is already

there. It just has to be brought sort of kicking and screaming

into the twentieth century. And it has to allow for the fact

that we have all of these capturing technologies, reproducing

technologies."

Ultimately, Joyce would like to see copyright laws

articulated by artists instead of politicians. "When Congress

makes these copyright laws and all these regulations, they don't

get any input from the artists at all," he says. "All the

lobbyists and businesspeople and label owners and record company

people are in their lobbying for their own interests, telling

Congress, `Yes, all this we're doing to protect the artist—poor,

helpless, ignorant artist who can't do anything for himself, who

needs us and our agents and our accountants to keep everything

straight.' And they [Congress] fall for all that, they don't know

any different."

According to Joyce, government and art just don't mix. "I

don't care if PBS loses all their funding," he says. "I'd like to

see the government get out of the arts. I'm real conservative on

that issue," he says. "The government should be hands off of art.

It never does any good—the influence is always to make it bland

and mediocre. They don't know anything about it. I would like to

see the government completely out of the arts, and all artists

either find private support or find a way to support themselves

by actually getting people to buy their work. You know—unheard

of! `Wow! We want to actually compete.'" [Laughs]

Fair Use not only chronicles Negativland's past legal

troubles over copyright: it could start a new chapter. The book

is like a paperback mirror of a Negativland sound collage: the

band gathered together material relevant to the story without

regard for ownership and reproduced them without permission.

Further lawsuits, then, are a possibility. (SST Records' Greg

Ginn sued the band for reprinting an SST press release in The

Letter U and the Numeral 2, a magazine-sized version of

Fair Use.) This time, however, Negativland is ready.

"If we get sued for this new book and record, I think my

first reaction—personally—would be to call up the attorney

representing whoever was suing us and say: `Are you out of your

mind?' [Laughs] 'Our defense, if you proceed with this

lawsuit, is going to be a fair use defense. It's a fair use of a

piece of audio in an audio collage about fair use, on a CD

called Fair Use, inside of a book called Fair

Use, which is all about fair use. And you are going to

lose.' And I don't care who it is. Any lawyer with half a brain

would have to pause and think about it. And it is why perhaps we

may be left alone even if it comes to the attention of someone

who doesn't like what we did. They'd say, 'Gee, Negativland

really almost—almost—looks like they want someone to sue

them, because they want to fight it and they want to change

things. And we don't want that to happen, so we'll just leave

them alone.'"

Hosler recognizes that Negativland's continued noisemaking

could provoke opposite results: sometimes the squeaky wheel gets

oiled, but sometimes the buzzing fly gets swatted first. "It

could be like the guy who very publicly resisted signing up for

Selective Service," he says, laughing. "There's all the people

who just quietly didn't sign up, but the guy who made a big stink

about it was prosecuted and tossed in jail. So someone else

could say, 'We need to set an example.' And what better example

to set than go after Negativland?"

© Deuce of Clubs

|