Ball Four

Jim Bouton (1970)

I don't know which is the most important book ever written about baseball, but the most important for me and multitudes of others will always be Ball Four. I first read it as a kid (many times), and again as an adult (many times). I'll probably continue to read it every few years as long as I live. Apart from the nostalgia of it, I still find the book humorous and human. But when I read it in 1970, at the age of nine, it was more like a revelation.

It wasn't a "tell-all"; it was a tell-it-like-it-is. It told all sorts of things a nine-year-old had no idea he needed to know. Come to find out, the ballplayers I idolized were very much like us kids—a bunch of dorks, mostly, just taller and older. The same kinds of bullshitting, back-biting, and infighting that went on among us kids—and I mean the exact same kinds—went on among full-grown adults. (We didn't yet have Twitter to teach us that.) More importantly, people in charge of adults were as foolish, hidebound, and unthinkingly habit-ruled as people in charge of children. This was important information for a kid being force-fed nonsense by the shovelful at home, school, and church.

There were of course things in Ball Four that I was too young to understand. (Hell, I didn't even know how to pronounce Bouton. I thought it was BOO-tun. Bouton wrote that it was pronounced BOW-ton, but that didn't help—was it bow as in bow tie, or was it bow as in the bow of a ship? I found out much later that it was the latter, but I don't know why they didn't just say bout, as in a boxing match, or about.) But what I could understand hit home for me, just when I needed it.

Only 13 years after its publication, Ball Four had so altered the map that it was already difficult to see how daringly honest it had been. In 1983 Nancy Marshall, ex-wife of pitcher Mike Marshall, wrote, "It was so long ago that Ball Four was published and so many controversial sports books have been written since then that hardly anyone realizes what a bombshell it was in 1970." Marshall and Bouton's wife, Bobbie, co-wrote a book in its own way as honest as Ball Four, describing what life was like being married to ballplayers. (I'll post some excerpts in due course but you can read a couple of contemporary articles about their book here and here.)

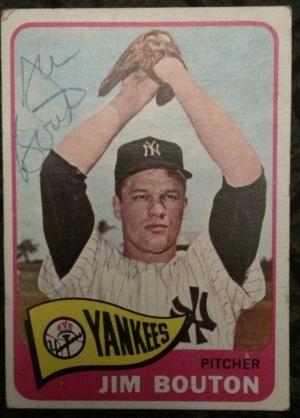

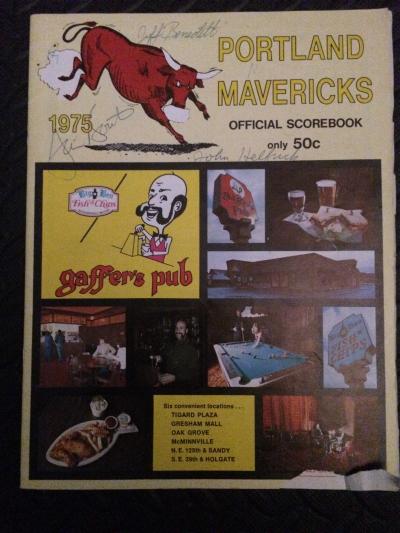

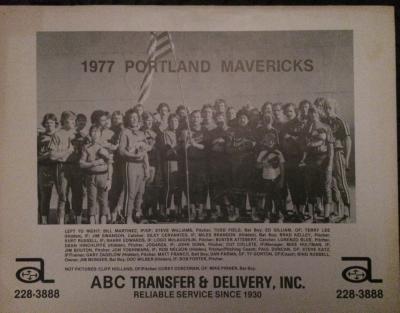

One of my greatest childhood thrills was getting to meet Bouton when I was a 13-year-old, after seeing him pitch a Portland Mavericks game. As he signed my program and a baseball card I'd brought with me I got to tell him how important his book had been to a little baseball-obsessed doofus in the desert. Thousands, if not tens of thousands, of people have thanked him similarly over the decades.

So long, Bulldog. And thanks again.

R.I.P. Jim Bouton

(These excerpts are mostly for my own use, which is why there are so many. I strongly suggest reading some to get the flavor and then buying and reading Ball Four in its entirety.}

Someone once asked Al Ferrara of the Dodgers why he wanted to be a baseball player. He said because he always wanted to see his picture on a bubblegum card. Well, me too. It's an ego trip. I've heard all the arguments against it. That there are better, more important things for a man to do than spend his time trying to throw a ball past other men who are trying to hit it with a stick. There are things like being a doctor or a teacher or working in the Peace Corps. More likely I should be devoting myself full-time to finding a way to end the war. I admit that sometimes I'm troubled by the way I make my living. I would like to change the world. I would like to have an influence on other people's lives.

I was piqued for a moment. But then I thought, what the hell, there are a lot of professions that rank even with baseball, or a lot below, in terms of nobility. I don't think there's anything so great about selling real estate or life insurance or mutual funds, or a lot of other unimportant things that people do with their lives and never give it a thought. Okay, so I'll save the world when I get a little older. I believe a man is entitled to devote a certain number of years to plain enjoyment and driving for some sort of financial security.

I signed my contract today to play for the Seattle Pilots at a salary of $22,000 and it was a letdown because I didn't have to bargain. There was no struggle, none of the give and take that I look forward to every year. Most players don't like to haggle. They just want to get it over with. Not me. With me, signing a contract has been a yearly adventure.

As soon as I got to the park I went right over to Marvin Milkes' office and we shook hands and he asked me if I had a nice flight. He also said, "There's been a lot of things said about the strike and I know you've said some things about it, but we're going to forget all that and start fresh. We have a new team and everybody starts with a clean slate. I'm giving some people a new opportunity. I've got a man in the organization who is a former alcoholic. I've even got a moral degenerate that I know of. But as far as I'm concerned we're going to let bygones be bygones and whatever has been said in the past—and I know you've said a lot of things—we'll forget all about it and start fresh." I said thanks. I also wondered where, on a scale of one to ten, a guy who talks too much falls between a former alcoholic and a moral degenerate.

This is the first time I've trained in Arizona. I think I'm going to like it. The park is in a beautiful setting—the center of a desolate area, flat, empty, plowed fields in all directions. And then, suddenly, a tremendous rocky crag rises abruptly to look down over the park. At any moment you expect to see a row of Indians on horseback charging around the mountain and into the park shooting flaming arrows. I'd always heard you couldn't work up a sweat in Arizona. Not true. I ran fifteen or twenty wind sprints and I can testify that anyone who can't sweat in Arizona hasn't tried.

Lots of holler out there in the infield. "Fire it in there, Baby." "C'mon, Joey." "Chuck it in there." And the word for that friends, is false chatter. You don't hear it as much during the season because nobody's nervous and nobody has to impress a coach who thinks you're trying harder if you holler, "Hey, whaddaya say?" You only hear it in spring training—and in high school baseball. I remember when I was in high school, even if we lost the game, the coach would say, "I liked your chatter out there, a lot of holler. That's what I like to see." So if you couldn't hit, you hollered.

Anyway, it took about a week before I could get it to knuckle at all. I remember once I threw one to my brother and hit him right in the knee. He was writhing on the ground moaning, "What a great pitch, what a great pitch." I spent the rest of the summer trying to maim my brother.

The family loves it in Arizona. We've taken a few rides out into the desert and looked at the cactus and the beautiful rock formations, and the kids are excited about the weather getting warm enough so they can use the pool. Kyong Jo, the Korean boy we adopted, is doing great with his English. Every once in a while he'll burp and say, "Thank you." But he's getting the idea.

They wanted to carry me off on a stretcher but I knew if my wife heard I was carried off the field she'd have a miscarriage. So I went off under my own power, bloody towel and all, and listened carefully for the ovation. I got it. Ovations are nice and some guys sort of milk them. Like Joe Pepitone. If he had just the touch of an injury he'd squirm on the ground for a while and then stand up, gamely. And he'd get his ovation. After a while the fans got on to him, though, and he needed at least a broken leg to move them.

Clever fellow, Marshall. He has even perfected a pick-off motion to second base that's as deadly as it is difficult to execute. He says one reason it's effective is that he leans backward as he throws the ball. I asked why, and he said, "Newton's Third Law, of course." Of course. Except the last time I tried his pick-off motion I heard grinding noises in my shoulder.

I once invested a dollar when Mantle raffled off a ham. I won, only there was no ham. That was one of the hazards of entering a game of chance, Mickey explained. I got back by entering a fishing tournament he organized and winning the weight division with a ten-pounder I'd purchased in a store the day before. Two years later Mantle was still wondering why I'd only caught that one big fish and why all the other fish that were caught were green and lively while mine was gray and just lay there, staring.

I've seen him close a bus window on kids trying to get his autograph. And I hated that look of his, when he'd get angry at somebody and cut him down with a glare. Bill Gilbert of Sports Illustrated once described that look as flickering across his face "like the nictitating membrane in the eye of a bird."

I remember one time he'd been injured and didn't expect to play, and I guess he got himself smashed. The next day he looked hung over out of his mind and was sent up to pinch-hit. He could hardly see. So he staggered up to the plate and hit a tremendous drive to left field for a home run. When he came back into the dugout everybody shook his hand and leaped all over him, and all the time he was getting a standing ovation from the crowd. He squinted out at the stands and said, "Those people don't know how tough that really was."

It was 55 degrees and blowing out there today, so I only watched a couple of innings of the intrasquad game. I was there long enough to see Marshall get hit pretty hard. Evidently the shorter hypotenuse didn't help him much. He just ran into Doubleday's First Law, which states that if you throw a fastball with insufficient speed, someone will smack it out of the park with a stick.

Houk sat next to me in the dugout and told me, very confidentially, "You know, you're having a helluva spring, a better spring than Dooley Womack, and I think you're just the man we need in the bullpen." What I wanted to say was: "I'm having a better spring than who? Dooley Womack? The Dooley Womack? I'm having a better spring than Mel Stottlemyre or Sam McDowell or Bob Gibson." That's what I should have said. Instead I just sat there shaking my head.

My fingers aren't strong enough to throw the knuckleball right. I've gone back to taking two baseballs and squeezing them in my hand to try to strengthen my fingers and increase the grip. I used to do that with the Yankees, and naturally it bugged The Colonel. The reason it bugged The Colonel is that he never saw anybody do it before. Besides, it wasn't his idea. "What are you doing?" The Colonel would sputter. "Put those baseballs back in the bag." Immediately Fritz Peterson would pick up two baseballs and start doing the same thing. One day Fritz got Steve Hamilton and Joe Verbanic and about three or four other pitchers to carry two balls around with them wherever they went. It drove The Colonel out of his mind. The following spring Fritz was removed as my roommate. The Colonel kept telling Fritz not to worry, that pretty soon he wouldn't have to room with "that Communist" anymore. And Fritz would say, "No, no, that's all right. I want to room with him. I like him. We get along great." And The Colonel would say, "Fine, fine. We'll get it straightened out."

Steve Hovley sidled over to me in the outfield and said, "To a pitcher a base hit is the perfect example of negative feedback."

After the game Bobbie and I were at a party with Gary Bell and his wife and Steve Barber and his. Gary's wife, Nan, said she'd been anxious to meet me since she'd read in the Pilot spring guidebook that some of my hobbies were water coloring, mimicry and jewelry-making. "Everyone else has hunting and fishing, so I figured you must be a real beauty. I mean, jewelry-making?" said Nan. "Make me some earrings, you sweet thing."

My wife and I burst out laughing when Gary asked me if I'd ever been on the roof of the Shoreham Hotel in Washington. The Shoreham is the beaver-shooting capital of the world, and I once told Bobbie that you could win a pennant with the guys who've been on that roof. "Pennant, hell," Gary said. "You could stock a whole league." I better explain about beaver-shooting. A beaver-shooter is, at bottom, a Peeping Tom. It can be anything from peering over the top of the dugout to look up dresses to hanging from the fire escape on the twentieth floor of some hotel to look into a window. I've seen guys chin themselves on transoms, drill holes in doors, even shove a mirror under a door. One of the all-time legendary beaver-shooters was a pretty good little left-handed pitcher who looked like a pretty good little bald-headed ribbon clerk. He used to carry a beaver-shooting kit with him on the road. In the kit there was a fine steel awl and several needle files. What he would do is drill little holes into connecting doors and see what was going on. Sometimes he was lucky enough to draw a young airline stewardess, or better yet, a young airline stewardess and friend. One of his roommates, a straight-arrow type—Fellowship of Christian Athletes and all that—told this story: The pitcher drilled a hole through the connecting door and tried to get him to look through it. He wouldn't. It was against his religion or something. But the pitcher kept nagging him. "You've got to see this. Boyohboyohboy! Just take one quick look." Straight-arrow finally succumbed. He put his eye to the hole and was treated to the sight of a man sitting on the bed tying his shoelaces. One of the great beaver-shooting places in the minor leagues was Tulsa, Oklahoma. While "The Star-Spangled Banner" was played you could run under the stands and look up at all kinds of beaver. And anytime anyone was getting a good shot, the word would go out "Psst! Section 27." So to the tune of "The Star-Spangled Banner" an entire baseball club of clean-cut American boys would be looking up the skirt of some female. Beaver-shooting can get fairly scientific. I was still in the minor leagues when we discovered that if you stuck a small hand mirror under a hotel room door—especially in the older hotels, where there were large spaces between the door and the floor—you could see the whole room just by looking at the mirror. This was a two-man operation: one guy on his hands and knees looking at the mirror, the other at the end of the hall laying chicky, as they say. We usually sprinkled some change around on the floor so you'd have a reason being down on it if anybody caught you. Spot a good beaver and you could draw an instant crowd. One time in Ft. Lauderdale we spotted this babe getting out of her bathing suit. The louvered windows of her room weren't properly shut and we could see right into the room. Pretty soon there were twenty-five of us jostling for position. Now, some people might look down on this sort of activity. But in baseball if you shoot a particularly good beaver you are a highly respected person, one might even say a folk hero of sorts. Indeed, if you are caught out late at night and tell the manager you've had a good run of beaver-shooting he'd probably let you off with a light fine. The roof of the Shoreham is important beaver-shooting country because of the way the hotel is shaped—a series of L-shaped wings that make the windows particularly vulnerable from certain spots on the roof. The Yankees would go up there in squads of 15 or so, often led by Mickey Mantle himself. You needed a lot of guys to do the spotting. Then someone would whistle from two or three wings away, "Psst! Hey! Beaver shot. Section D. Five o'clock." And there'd be a mad scramble of guys climbing over skylights, tripping over each other and trying not to fall off the roof. One of the first big thrills I had with the Yankees was joining about half the club on the roof of the Shoreham at 2:30 in the morning. I remember saying to myself, "So this is the big leagues."

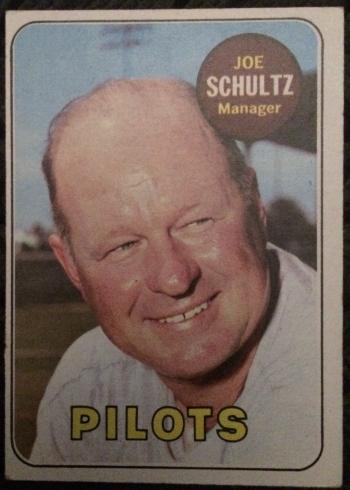

Today Joe Schultz said, "Men, you got to remember to touch all the bases." The occasion was a meeting after our glorious 19-4 victory in which one of the guys on the Cleveland club missed third base and was called out. So the lesson for today was "Touch those bases. Especially first."

My wife reminds me that I never got clobbered in Seattle when I was first working on my knuckleball and she suggests I go with it all the way. I give her opinion a lot of weight. We were both freshmen at Western Michigan when we met and all she would talk about was baseball. When I told her I was going out for the freshman team, she said, "You don't have to do that because of me." I didn't tell her it wasn't because of her. And then, when she first saw me pitch she said, "That's a big-league pitcher if I ever saw one." So she's a hell of a scout. Knuckleballs. Hmm.

I've had some pretty good advice from my family. My dad especially. He helped pick the college I went to and got me into it. My services as a pitcher were not exactly in great demand. I pitched a no-hitter in my senior year in high school but I was only 5-10 and 150 pounds. My dad got a look at the Western Michigan campus, fell in love with the beauty of it, thought I'd love the baseball stadium and had me apply. I didn't hear anything for a long while, but my dad was real cool. He took a bunch of my clippings—all six of them—had copies made and sent them to the baseball coach there, Charley Maher. He wrote, "Here's a fellow that may help our Broncos in the future," and signed it "A Western Michigan baseball fan." A week later I was accepted.

When I got home at about nine o'clock my mom and dad were playing bridge with some friends, and when I walked in the door I said, "Dad, you're not going to believe it, but I pitched the best game of the tournament and the scouts want to sign me. Dad, they're talking about real big money." My dad looked at his cards. "Two no trump," he said. He didn't really believe me. Then the phone rang and I said, "Dad, that's a scout on the phone, I know it is. What should I tell him?" "Tell him $50,000," he said. "Three spades." He still didn't believe me. I went over to the phone, and sure enough it was a scout from Philadelphia. "My dad says $50,000," I said. The scout said, "Fine. We want you to fly to Philadelphia and work out with the team." That ended the card game.

I struck out the first hitter I faced on four pitches, all knuckleballs. (Don't ask me who he was; hitters are just meat to me. When you throw a knuckleball you don't have to worry about strengths and weaknesses. I'm not sure they mean anything, anyway.)

I guess it wasn't too good for my elbow, though. When I got through pitching it felt like somebody had set fire to it. I'll treat it with aspirin, a couple every four hours or so. I've tried a lot of other things through the years—like butazolidin, which is what they give to horses. And D.M.S.O.—dimethyl sulfoxide. Whitey Ford used that for a while. You rub it on with a plastic glove and as soon as it gets on your arm you can taste it in your mouth. It's not available anymore, though. Word is it can blind you. I've also taken shots—novocain, cortisone and xylocaine. Baseball players will take anything. If you had a pill that would guarantee a pitcher 20 wins but might take five years off his life, he'd take it.

Ruben Amaro is here with the Angels and I was happy to see him. We were good friends in New York. He's the kind of guy, well, there's a dignity to him and everybody likes and respects him. He's outspoken and has very strong opinions but he never antagonizes people with his positions the way I sometimes do. I wish I could be more like him.

Ding Dong Bell gets his first start against Arizona State U. tomorrow and he says he's not ready. I told him it's no sweat because if anybody makes this team it's going to be old Ding Dong, no matter what happens this spring. He said he realized that, and he's going to go out there and just keep from getting hurt. Pitching against a college team, you can't look good no matter what. If you do well, they're just college kids. If you don't, you're a bum. Yet the kids are in better shape than we are and can be a pain in the ass.

Curt Blefary is another guy with classically bad hands. When he was with Baltimore, Frank Robinson nicknamed him "Clank," after the robot. Once the team bus was riding by a junkyard and Robinson yelled for the driver to stop so Blefary could pick out a new glove. (If you're going to shake hands with a guy who has bad hands you are supposed to say, "Give me some steel, Baby.")

The whole anthem-flag ritual makes me uncomfortable, and when I was a starting pitcher I'd usually be in the dugout toweling sweat off during the playing of the anthem.

How many inches are there between the belt and the knee? How many pitches can you control to that tolerance? How many pitching coaches are second-guessers? Answers: Eighteen inches. Very few. Most.

We were toasting marshmallows in the backyard and I was sharpening a stick to put through the marshmallows when I sliced off most of the tip of my left thumb. I went to the clubhouse to have it repaired. Someone saw the ugly slice and immediately a crowd formed, as it always does when something gory is on exhibit. We like to say about ourselves—we baseball players—that we're ghouls. I remember one time it was standing room only in Ft. Lauderdale when Jake Gibbs got hit on the thumb and they had to drill a hole through his nail to relieve the pressure. I had a front-row seat myself. The drill boring through the nail started to smoke and when it hit paydirt Jake jerked his hand and the drill was ripped out of the trainer's hand and here's Jake's hand waving in the air with the drill still hanging from the hole in his nail. One of the great thrills of the spring.

Another time I said, "Hey, Coates, you endorsing iodine?" And he said, cautiously, "Why?" "Because I saw your picture on the bottle."

We had a visit from Commissioner Bowie Kuhn today. The visit was preceded by the usual announcement from the manager: "All right, let's get this thing over with as quickly as we can." What it really means is: "Okay you guys, you can listen. But don't ask any questions."

All of which for some reason reminds me of one of our bullpen occupations: choosing an All-Ugly Nine. Baseball players are, of course, very gentle people. If we happen to see some fellow who is blessed with a bad complexion we immediately call him something nice, like "pizza face." Or other sweet little things like: "His face looks like a bag of melted caramels." "He looks like he lost an acid fight." "He looks like his face caught on fire and somebody put it out with a track shoe." Some famous all-uglies are Danny Napoleon ("He'd be ugly even if he was white," Curt Flood once said of him); Don Mossi, the big-eared relief ace on the all-ugly nine (he looked like a cab going down the street with its doors open); and Andy Etchebarren, who took over as catcher from Yogi Berra when the famed Yankee receiver was retired to the All-Ugly Hall of Fame.

Had a long chat with Steve Hovley in the outfield. He's being called "Tennis Ball Head" because of his haircut, but his real nickname is Orbit, or Orbie, because he's supposed to be way out. Hovley is anti-war and I asked him if he ever does any out-and-out protesting in the trenches. He said only in little things. For instance, when he takes his hat off for the anthem he doesn't hold it over his heart. I feel rather the same way. The whole anthem-flag ritual makes me uncomfortable, and when I was a starting pitcher I'd usually be in the dugout toweling sweat off during the playing of the anthem. We agreed we're both troubled by the stiff-minded emphasis on the flag that grips much of the country these days. A flag, after all, is still only a cloth symbol. You don't show patriotism by showing blank-eyed love for a bit of cloth. And you can be deeply patriotic without covering your car with flag decals. Hovley said he didn't mind being called Orbit. "In fact I get reinforcement from it," he said. "It reminds me that I'm different from them and I'm gratified." What's different about Hovley is that he'll sit around reading Nietzsche in the clubhouse and sometimes he'll wonder why a guy behaves a certain way. In baseball, that's a revolutionary.

Ray Oyler was racked up at second base by Glenn Beckert of the Cubs, and when he came back to earth he was heard to call Beckert a son of a bitch. This is not on the same order as motherfucker, but he didn't have a lot of time to think. It has become the custom in baseball to slide into second base with a courteous how do you do, so when somebody does slide in hard everybody gets outraged and vows vengeance. A few years ago Frank Robinson slid into Bobby Richardson with murderous aplomb and the Yankees were visibly shocked. How could he do that to our Bobby? We'll get him for that. Actually this was a National League play and the Yankees simply weren't used to it.

Schultz said we weren't in shape and that we were making physical mistakes that we wouldn't if we were—in shape, I mean. (I'm not sure I understood that.) But then he obviously felt he'd hurt our feelings and tried to take it all back. "Shitfuck," he said, using one of his favorite words ("fuckshit" is the other). "Shitfuck. We've got a damned good ballclub here. We're going to win some games."

Sain would compare pitching to a golfer chipping to a green and say that if you tried for the cup you might miss the green. The thing to do was just hit the green, pitch to a general area.

[What do I know, but that seems like a terrible idea, the opposite of the shooting maxim, "Aim small, miss small." — Ed.]

Control was our big problem, Sal said. We've walked eighty and struck out only forty and the ratio should be the other way around. He's absolutely right. But he's got the wrong reason. Then he surprised me by mentioning my name. "Some of you guys think you can get by on only one pitch," he said. "You can't do it. Nobody is a one-pitch pitcher." He added: "Bouton, they're just waiting for your knuckleball. You got to throw something else." In the immortal words of Casey Stengel, "Now, wait a minute." Are we trying to win ballgames down here or are we trying to get ready for the season? What I have to learn is control of the knuckleball. And I'm not going to learn it by throwing fastballs. I tried to explain that to Sal after the meeting and he said, well, yes, but I should have some other pitches to set up the knuckleball. I said I agreed with him 100 percent. I said it because I'm in a shaky position here and the first thing you got to do is make the ballclub, and you don't make ballclubs arguing with pitching coaches. Afterward in the outfield we talked about one-pitch pitchers. Ryne Duren was a one-pitch pitcher. His one pitch was a wild warm-up. Ryne wore glasses that looked like the bottoms of Coke bottles, and he'd be sort of steered out to the mound and he'd peer in at the catcher and let fly his first warm-up pitch over the screen and the intimidation was complete. All he needed was his fastball and hitters ducking away. And just for the hell of it I got into a conversation with Maglie about when he was a great pitcher, and I asked him what he used to get the Dodgers out with in his glory days with the Giants. "Ninety-seven snappers," Sal Maglie said. So much for one-pitch pitchers.

Only once in the years I've been pitching has anybody ever ordered me to throw a duster. It was last year at Seattle and Joe Adcock, a man I like, was the manager. I came into a game in relief and John Olerud, the catcher, came out and said, "Joe wants you to knock this guy on his ass." I couldn't believe it. So I said something clever. "What?" "Joe wants you to knock this guy on his ass." "I just got in the game. I got nothing against this guy." "Well, he says to knock him on his ass." "Bullshit," I said. "I haven't thrown that much. I'm not sharp enough to know where the hell I'm throwing the ball. I'm not going to do it. You go back there and tell him that you told me to knock him down and that I refused and if he wants to say something afterward let him say it to me." Adcock never said a word. I mean, what if I screw up a man's career? I'm going to have that on my conscience for... well, for weeks maybe. The fact is, though, that I once did throw at a guy. I mean to maim him. His name was Fred Loesekam. He was in the White Sox organization and he was a bad guy. He liked to slide into guys spikes high and draw blood. During warm-ups he liked to scale baseballs into the dugout to see if he could catch somebody in the back of the head. He even used our manager for target practice. So I took my shots at him. We all did. Once I threw a ball at him so hard behind his head that he didn't even move. The ball hit his bat and rolled out to me, and I threw him out before he got the bat off his shoulder. When you throw a ball behind a hitter's head you're being serious. His impulse is to duck backwards, into the ball. If you're not so serious and all you want to do is put a guy out for a piece of the season, you aim for the knee. An umpire will give you two or three shots at a guy's knee before he warns you.

And don't believe it when you hear that a pitcher can throw the ball to a two-inch slot. A foot and a half is more like it, I mean with any consistency. When I first came up I thought major-league pitchers had pinpoint control, and I was worried that the best I could do was hit an area about a foot square. Then I found out that's what everybody meant by pinpoint control, and that I had it.

I was also rather sad about Claude "Skip" Lockwood. Hate to lose a funny man. The other day we were talking about pitching grips in the outfield (it was the day after I'd been mildly racked up by a couple of doubles) and Lockwood asked me, "Say Jim, how do you hold your doubles?" About a week ago Lockwood said, "Hey, the coaches are calling me Fred. You think it means anything?" "Don't worry about it, Charley," I told him. And today he came over and said he was a little confused, that he didn't know which field he was supposed to be working on. He said he guessed things were getting better for him. "Last week I didn't know who I was. Now all I don't know is where."

There was a notice on the bulletin board asking guys to sign up to have their cars driven to Seattle. Price $150. The drivers are college kids. I think I'd prefer Bonnie and Clyde. I say this because I remember college and how I drove an automobile in those days and I would not have hired me to drive my car. Still, a lot of guys put their names on the list—very tentatively.

Steve Hovley was dancing to a tune on the radio and somebody yelled, "Hove, dancing is just not your thing." "Do you mind if I decide what my thing is?" Hovley said. So I asked him what his thing was. "I like sensual things," he said. "Eating, sleeping. I like showers and I like flowers and I like riding my bike." "You have a bike with you?" "Certainly. I rent one. And I ride past a field of sheep on the way to the park every day and a field of alfalfa, and sometimes I get off my bike and lie down in it. A field of alfalfa is a great place to lie down and look up at the sky." I sure wish Hovley would make the team.

I haven't been pitching very well and I think that as a result my sideburns are getting shorter. Also, instead of calling Joe Schultz Joe I'm calling him Skip, which is what I called Ralph Houk when I first came up. Managers like to be called Skip.

A revelation about Joe Schultz. Mike Hegan has been hitting the hell out of the ball and at this point is to the Seattle Pilots what Mickey Mantle was to the Yankees. Today he was hit on the arm by a fastball, and when Joe got to him and said, "Where'd you get it, on the elbow?" Hegan said, "No. On the meat of the arm, the biceps." "Oh shit, you'll be okay," Joe said. "Just spit on it and rub some dirt on it." Hegan couldn't move three of his fingers for an hour. But it didn't hurt Joe at all.

Riding back to Tempe I had a beautifully serene feeling about the whole day, which shows how you go up and down an emotional escalator in this business. It was my first really serene day of the spring and I felt, well, I didn't care where the bus was going or if it ever got there, and I was content to watch the countryside roll by. It was desert, of course, with cactus and odd rock formations that threw back the flames of the setting sun. The sun was a golden globe, half-hidden, and as we drove along it appeared to be some giant golden elephant running along the horizon

Ran my long foul-line-to-foul-line sprints in the outfield and kept myself going by imagining I was Jim Ryun running in the Olympics: I'm in the last fifty yards and I'm going into my finishing kick and thousands cheer. If I'm just Jim Bouton running long laps very little happens. Let's see. Here's the World War I flying ace....

Bill Stafford and Jimmy O'Toole got their releases today. Stafford hopes to hook on with the Giants (I don't see how) and O'Toole is shopping around. I've had some big discussions with O'Toole. His father is a cop in Chicago and was in on the Democratic Convention troubles. I'd been popping off, as usual, about what a dum-dum Mayor Daley was and O'Toole said hell, none of those kids take baths and they threw bags of shit at the cops, and that's how I found out his father was a cop. Even so, I feel sort of sorry for him because he's got about eleven kids (I should feel more sorry for his wife) and he seemed a forlorn figure as he packed his stuff. I told him good luck but somehow I didn't get to shake his hand, and I feel bad about that. It's funny what happens to a guy when he's released. As soon as he gets it he's a different person, not a part of the team anymore. Not even a person. He almost ceases to exist. It's difficult to form close relationships in baseball. Players are friendly during the season and they pal around together on the road. But they're not really friends. Part of the reason is that there's little point in forming a close relationship. Next week one of you could be gone. Hell, both of you could be gone. So no matter how you try, you find yourself holding back a little, keeping people at arm's length. It must be like that in war too.

Jake Gibbs of the Yankees once ordered pie a la mode in a restaurant and then asked the waitress to put a little ice cream on it.

Marvin Miller is coming around tomorrow to hand out some checks for promotions the Players' Association was paid for. So everybody was busy reminding everybody else not to tell the wives. We get little checks for a lot of things, like signing baseballs, which are then sold. In our peak years with the Yankees we were getting around $150 for signing baseballs. It's all pocketed as walking-around money. The wives don't know about it. Hell, there are baseball wives who don't know about the money we get for being in spring training, or that we get paid every two weeks during the season. John Kennedy, infielder, says that when his wife found out about the spring money she said, "Gee whiz, all that money you guys get each week. How come you've never been able to save anything?" And John said, "We just started getting it, dear. It's a brand-new thing."

Joe Schultz asked Wayne Comer, outfielder, how his arm felt. Comer said he wasn't sure, but that every time he looked up there were buzzards circling it.

Today Joe Schultz said, "Many are called, few are chosen." He said it out of the clear blue, several times, once to Lou Piniella. Said Lou: "Is that a bad sign?" I said I didn't know. But I did. And it was.

Would you believe that we were playing a ballgame in Yuma, the winter home, as they say, of the San Diego Padres, which is a place you pass through on the way to someplace else, a place that doesn't even have a visiting clubhouse, so that we had to dress on the back of an equipment truck, and in the middle of a game before about twelve people, one of them yelled at us, "Ya bums, ya!" I mean, would you believe it?

Said Joe: "Boys, if you don't know who you're going to play you don't have your head in the game." The guy who asked the question was Lou Piniella, and now he knows what Joe meant by "Many are called, few are chosen." Goodbye Lou.

Bell is a funny man and, along with Tommy Davis, is emerging as one of the leaders of the club. He's got an odd way of talking. Instead of saying, "Boy, that's funny," he'll wrinkle up his face and say, "How funny is that?" Or he'll say, "How fabulous are greenies?" (The answer is very. Greenies are pep pills—dextroamphetamine sulfate—and a lot of baseball players couldn't function without them.)

Sometimes you'll get this kind of conversation: "Gee, your wife was great last night." "Oh, she wasn't all that great." "You should have been there earlier. She was terrific."

Johnny Podres, the old Dodger who seems to be making it with the San Diego Padres (that's sort of nice, Podres of the Padres).

[See also: Jose Cardenal of the Cardinals. — Ed.]

On the airplane, Darrell Brandon, sitting next to me, said, "You like to read a lot, don't you?" "Yeah," I said cleverly. "Does it make you smart?" He wasn't being sarcastic. I think he really wanted to know. "Not really," I said. "But it makes people think I am." Actually I was somewhat embarrassed by the question. In fact I do like to read on airplanes, but when I do I'm not in on the kidding and the small talk, so as a result I'm an outsider. I've resolved not to be an outsider this year. I'm not reading so much and no one can accuse me of playing the intellectual. And here I get caught up in a magazine article and Darrell Brandon is asking if reading makes you smart.

A little more about the new Bouton image. If the guys go out to a bar after a game for a few drinks, I'm going too. I'm going to get into card games on airplanes. I don't like bars much, and card games bore me, but I'm going to do it. If you want to be one of the gang, that's one way to do it. It's odd, but you can be seven kinds of idiot and as long as you hang around with the boys you're accepted as an ace. Johnny Blanchard of the Yankees was an ace. He was just another jocko, but he was an ace because he was always out with Mickey Mantle and the boys, drinking, partying, playing cards. Every once in a while, just to enhance his image, he'd smack some poor guy off a bar stool and that was great. Johnny Blanchard was one of the boys. Why should I be one of the boys? Why should I yield to the jockos? Oh, I'm not going to hold back if something comes up I feel strongly about, but I'm going to soft-pedal it a bit, at least at the beginning, until I'm sure I can make this club. I really believe that if you're a marginal player and the manager thinks you're not getting along with the guys it can make the difference. I'm positive that the one reason Houk got rid of me was that I'd made a lot of enemies on the club (including Houk, I guess) simply because I refused to go along with the rules they set up.

And it could cost you too. When Joe Garagiola was running "The Match Game" on television, a lot of the Yankees, almost all of them, were getting on the show. I mean even Steve Whitaker. And me, the articulate Jim Bouton, spontaneously witty, always at ease in front of the camera, never got a call. This year, though, it's a new Bouton. At least until I win some ballgames.

Today, while we were sitting in the bullpen, Eddie O'Brien, the All-American coach, said, just after one of our pitchers walked somebody in the ballgame, "The secret to pitching, boys, is throwing strikes." Gee, Eddie! Thanks.

And if he had come to me, I probably would have grooved one for him. Not for money, just for the hell of it. Sorry kids, things like that happen. Phil Linz was batting .299 going into the last game of the season at Modesto and asked the other catcher to help him get to .300. "When you come up I'll have the third baseman play real deep," the catcher said. "All you have to do is lay down a bunt and beat it out." That's exactly what happened. Phil got the hit for his .300 average and got the manager to take him out of the game. Now it's in the record books forever that Phil Linz hit .300. The same thing happened with Tommy Davis. He was hitting .299 for the Mets and playing against his old teammates, the Dodgers. Johnny Roseboro was catching. "Hey, Baby, you're my main man," Davis said. "How about a little help?" Roseboro said sure and told him what was coming. Davis got his hit and had his .300 batting average.

So far I haven't heard any of the white guys say, "Tommy, what are you doing for dinner tonight?" Maybe it will come. Maybe.

I asked around to find out who put it up, but I couldn't, although I eventually decided it must have been either Clete Boyer, another one of my boosters, or Maris. So one day when they were standing together in the outfield I went over and said, "I wish you guys would tell me who put that clipping up on the board, because I'd like to get my hands on the gutless son of a bitch who did it." And although Maris had already denied to me that he put up the clipping, he said, "Don't call me gutless." Somehow I managed not to get into a fight with him. But I felt I'd won the battle of wits.

I thought the Salmon trade was pretty good for us because we didn't really have a spot for him. But he was very disappointed. He slammed the door when he left Joe's office. I know he counted on going to Seattle. He spent the winter up there and went to a lot of promotional dinners and leased an apartment and rented furniture, the works. Now it's Baltimore instead. Life in the big leagues.

We were talking about what we ought to call Brabender when he gets here. He looks rather like Lurch of the "Addams Family," so we thought we might call him that, or Monster, or Animal, which is what they called him in Baltimore last year. Then Larry Haney told us how Brabender used to take those thick metal spikes that are used to hold the bases down and bend them in his bare hands. "In that case," said Gary Bell, "we better call him Sir."

Bill Henry retired today, just like that. First he makes the team, then he walks in on Joe Schultz and announces his retirement. Joe told us about it and said that he admired the man, that he had a lot of guts to walk out. John Morris, who was brought up from the Vancouver squad to replace Henry, was pretty frisky, like he'd just gotten a reprieve from the Governor. He said he had some long talks with Henry—which is something, because when you say hello to Henry he is stuck for an answer—and thinks he quit because he was holding back a young player. "What am I doing keeping younger guys from a chance to earn a living?" he said to Morris. "I'm forty-two years old. I've had thirteen years in the big leagues. I don't really belong here." During the meeting Joe Schultz said, "It takes a lot of courage for a guy to quit when he thinks he can't do the job anymore." So I opened my big yap and said, "If that's the case a lot of us ought to quit." Which gave Sal Maglie the chance to say, very coolly, "Well, use your own judgment on that." I'm not sure Sal likes me. Today Joe Schultz said, "Well, boys, it's a round ball and a round bat and you got to hit it square."

Bruce Henry, the Yankee road secretary, is one of my main men. He hated to buy bats for me. He always claimed I didn't need them. When he finally did, he had them inscribed not with my name, but my batting average—.092. And once when I complained that the people I'd given passes to were upset about getting poor seats, he said, "How'd they like the price?"

There was a lot of grousing about the uniforms. It isn't only that they don't fit (no baseball uniforms fit, possibly because you are carefully measured for them). It's that they're so gaudy. I guess because we're the Pilots we have to have captain's uniforms. They have stripes on the sleeves, scrambled eggs on the peak of the cap and blue socks with yellow stripes. Also there are blue and yellow stripes down the sides of the pants. We look like goddam clowns.

[But not as much as the 1980 Tucson Toros did. — Ed.]

Mike Hegan hit the first home run for the Pilots and Joe Schultz, jumping up and down in the dugout, clapped his hands and actually yelled, "Hurray for our team." When we came into the clubhouse, all of us yelling and screaming like a bunch of high school kids, Joe Schultz said, "Stomp on 'em. Thataway to stomp on 'em. Kick 'em when they're down. Shitfuck. Stomp them. Stomp them good."

Today Joe Schultz said to the clean-shaven Rocky Bridges, Los Angeles coach, "Hey Rocky, how's your old mustache?"

Coaches have little real responsibility, so it seems to me they should, at the very least, try to help club morale—cheer guys onward and upward, make jokes and smooth out little problems before they become big ones. O'Brien and Plaza are officious types, though, and cause more trouble than they smooth over. And because they try to find things to do they become nothing but annoyances. Like O'Brien will say to Jack Aker, "Jack, you're in the bullpen tonight." Jack has been in the bullpen for eight years. Another example: It is customary for players to pair off and throw easily on the sidelines before a workout or a game. So as I reached into the ballbag to grab some baseballs for the guys, Plaza said, "What are you going to do with those baseballs, Bouton?" "I'm just going to take three or four out to the field because a few guys asked me to." "Just take one." "Yes, sir."

Standing around the outfield the conversation turned to religion. Don Mincher said he came from a very religious home and used to go to church every Sunday where people did things like roll in the aisles. He said there was a big circle of numbers on the church wall and when your number came up with somebody else's number you had to visit them and have a prayer meeting. As he got older Minch would say, "Well, let's have a few beers first." They didn't think that was very religious of him.

Going over the hitters is something you do before each series, and before we went against the mighty Angels, Sal Maglie had a great hint for one of their weaker hitters, Vic Davalillo. "Knock him down, then put the next three pitches knee-high on the outside corner, boom, boom, boom, and you've got him." Everybody laughed. If you could throw three pitches, boom, boom, boom, knee-high on the outside corner, you wouldn't have to knock anybody down. It's rather like telling somebody if he'd just slam home those ninety-foot putts he'd win the tournament easily.

Before today's game Joe Schultz said, "Okay men, up and at 'em. Get that old Budweiser."

A kid named Tom Berg, who belongs to the Seattle organization and goes to school here, came over to work out with the club. And before the workout he was in the clubhouse shaving off his nice long sideburns. He got the word that Dewey Soriano, who is the president of the club, thought he would look better with shorter sideburns. Well, I think Dewey Soriano would look better if he lost weight.

With Hovley gone, Mike Marshall is probably the most articulate guy on the club, so I asked him if he had as much trouble communicating as I've had and he said, "Of course. The minute I approach a coach or a manager I can see the terror in his eyes. Lights go on, bells start clanging. What's it going to be? What's this guy want from me? Why can't he be like everybody else and not bother me? It's almost impossible to carry on a conversation or get a direct answer to a direct question." In baseball they say, "He's a great guy. Never says a word."

So I said, "Well, if I do real good down there, I'd like to come back." I expected him to say, "Of course. You do good down there and we'll yank you right back here, stick you in and you'll win the goddam pennant for us." Or something reassuring like that. Instead Joe Schultz said, "Well, if you do good down there, there's a lot of teams that need pitchers." Good grief. If I ever heard a see you later, that was it.

Finally, Sal Maglie: "Well, pitch around him." When the meeting was over, Gary added up the pitch-around-hims and there were five, right in the beginning of the batting order. So according to Sal Maglie, you start off with two runs in and the bases loaded.

Finally, Sal Maglie: "Well, pitch around him." When the meeting was over, Gary added up the pitch-around-hims and there were five, right in the beginning of the batting order. So according to Sal Maglie, you start off with two runs in and the bases loaded. It's like the scouting reports we used to get on the Yankees about National League teams. We'd get the word that this guy couldn't hit the good overhand curve. Well, nobody hits the good overhand curve. In fact, hardly anybody throws the good overhand curve. It's a hard pitch to control and it takes too much out of your arm. And the word on Tim McCarver of the Cards was that Sandy Koufax struck him out on letter-high fastballs. Which is great advice if you can throw letter-high fastballs like Koufax could.

Got a letter today from two girls who were members of my fan club. They'd read the article in Signature about us adopting Kyong Jo and wanted to congratulate us and wish me luck with my new team. I really liked that fan club. I enjoyed being a big-league player and having people recognize me and having little kids get a charge out of meeting me. I remember what it was like when I was a kid and what a thrill I got just watching Willie Mays climb out of a taxicab. So the fact that I had my own personal fan club (would you believe an annual dinner and a newspaper called All About Bouton?) always pleased me. Of course I realized how old I'm getting and how quickly time passes when I heard that one of the fan-club members was in Vietnam. It just doesn't seem right that a member of my fan club should be fighting in Vietnam. Or that anybody should be.

I was a big New York Giant fan when I lived in New Jersey as a kid and then we moved to Chicago. I used to go to all the Cub—Giant games out there. And I remember once leaning over the dugout trying to tell Al Dark how great he was and how much I was for him and, well, maybe get his autograph too, when he looked over at me and said, "Take a hike, son. Take a hike." Take a hike, son. Has a ring to it, doesn't it? Anyway, it's become a deflating putdown line around the Bouton family. Take a hike, son.

There's nothing like walking into a minor-league clubhouse to remind you what the minors are like. You have a tendency to block it. It was cold and rainy in Tacoma when I went there to meet the Vancouver club and the locker room was shudderingly damp, small and smelly. There's no tarpaulin on the field, so everything is wet and muddy and the dirt crunches underfoot on the cement. The locker stalls are made of chicken wire and you hang your stuff on rusty nails. There's no rubbing table in the tiny trainer's room, just a wooden bench, and there are no magazines to read and no carpet on the floor and no boxes of candy bars. The head is filthy and the toilet paper is institutional-thin. There's no bat rack, so the bats, symbolically enough, are stored in a garbage can. There's no air-conditioning and no heat, and the paint on the walls is peeling off in flaky chunks and you look at all of that and you realize that the biggest jump in baseball is between the majors and Triple-A. The minor leagues are all very minor. There's no end to the humiliation. The kid in the clubhouse asked me what position I played.

Had a talk with Bob Tiefenauer about his knuckleball and he said he'd recently gotten a good tip from Ed Fisher. He says that when you're pitching with the wind at your back (which is very bad for the knuckler) you throw the ball harder. This seems to keep it out ahead of the wind and it knuckles pretty good. Tief says it sounds crazy, but there's logic to it and it seems to work. I'll have to remember that.

I've also been reflecting on Joe Schultz. I'm afraid I'm giving the impression I don't like him or that he's bad for the ballclub. Neither is true. I think Joe Schultz knows the guys get a kick out of the funny and nonsensical things he says, so he says them deliberately. If there's a threat to harmony on the club I think it comes from the coaching staff. On the other hand, it has been said that harmony is shit. The only thing that counts is

Do you know that ethyl chloride can be fun? This is a freezing agent kept around to cut the pain of cuts, bruises, sprains and broken bones. It comes in a spray can and it literally freezes anything it touches; hair, skin, blood. Also ants, spiders and other animals. The way you have fun with ethyl chloride is spray it on a guy who isn't looking. First thing he knows there's a frozen spot on his leg and the hair is so solid it can be broken off. Or you spray it on crawling creatures. They're frozen, they thaw and they resume their appointed rounds. Once we froze and thawed one bug thirty times just to see if it could be done. It can. Hot-feet, or hot-foots, depending on your attitude toward the language, can also be fun if your life is drab and empty and puerile and full of Phil Rizzuto. I once gave Phil my famous atomic bomb hot-foot, which consists of four match heads stuck inside another match. It was such a lovely hot-foot his shoelaces caught fire and the flames were licking at his pants cuff. One of the great hot-foots (hot-feet?) of all time was administered to Joe Pepitone by Phil Linz. The beauty part was that Pepitone was giving a hot-foot to somebody else at the time and just as he started to turn around and grin at the havoc he had wrought, a look of horror crossed his face and he began to do an Indian dance. The hot-footer had been hot-footed (feeted?) himself. Joe Pepitone is a gas.

On the plane I discovered that Greg Goossen is afraid to fly. On the takeoff he wrapped himself around his seatbelt in the fetal position, his hands over his eyes. Then, as we were landing, he went into frenzied activity, switching the overhead light on and off, turning the air blower on and off, right and left, opening and closing his ashtray and giving instructions into a paper cup: "A little more flap, give me some more stick, all right, just a little bit, okay now, level out." I asked him, "What's the routine?" "I always feel better when I land them myself," Goose explained.

Having been sent to the minors for at least parts of the last three seasons now, I've become somewhat defensive about it. It's disturbing to be considered a failure, to have a stigma attached to you just because you're sent down. For the fact is, that by any sane comparative standard, I'm much better at my job, even in Triple-A, than most successful professional people are in theirs. As a Triple-A player I'm one of the top thousand baseball players in the country, and when it's considered how few actually make it out of the hundreds of thousands who try, it's really a fantastic accomplishment. So I don't feel like a failure, and anybody who is guilty of thinking I am will be sentenced to a long conversation with Joe Schultz's liverwurst sandwich.

Jim Coates pitched against us tonight and beat us 4-1. Coates, as has been noted, could pose as the illustration for an undertaker's sign. He has a personality to match. He was the kind of guy who used to get on Jimmy Piersall by calling him "Crazy." Like, "Hey, Crazy, they coming after you with a net today?" Piersall used to get mad as hell and call Coates a lot of names, the most gentle of which was thermometer, but it didn't seem to hurt the way he played. I remember a game in Washington. Piersall was playing center field and Coates was giving him hell from the Yankee bullpen. Piersall was turning away from the game to give it back when somebody hit a long fly ball to left-center and Piersall had to tear after it. All the time he was running he was screaming at Coates, and when he got up to the fence he climbed halfway up it, caught the ball, robbing somebody of a home run, and threw it in. But not for a second did he stop yelling at Coates.

Coates was famous for throwing at people and then not getting into the fights that resulted. There'd be a big pile of guys fighting about a Coates duster and you'd see him crawling out of the pile and making for the nearest exit. So we decided that if there was a fight while Coates was pitching, instead of heading for the mound, where he was not likely to be, we'd block the exits. There was, of course, no fight. We'd all rather talk than fight.

It's great to be young and in Hawaii. Not only did I pitch in my seventh straight game and get my third save, but I had a smashing bowl of siamin, corn on the cob and teriyaki out in the bullpen. Major-league bullpen. We get up around ten in the morning, put on our bathing suits, go down to the beach for three or four hours, come back to have a nice home-cooked meal (we all have kitchenettes and share the cooking), do some shopping and get out to the ballpark at around five. Sheldon brings a radio down to the bullpen and always asks if we want to listen to a ballgame or music. Sheldon, you must be kidding. Talk in the bullpen turned to Joe Schultz, and I recounted what he'd told me when he sent me down. Everybody was surprised that I didn't get the recording: "This is a recording. Pitch two or three good games and you'll be right back up here again. This is a recording."

Also a beaver-shooting story was told. It seems that the Detroit bullpen carried a pair of binoculars and a telescope. The binoculars were used to spot an interesting beaver in the stands and then the telescope was used to zero in. So when the guy using the binoculars spotted a likely subject he'd say, "Scope me."

The reason I suffer from mai tai poisoning so often is that the other guys can drink them with no effect at all while I get drunk. They insist I come along so that they can, as they say, put the hurt on my body. Then in the morning they invite me for breakfast so they can observe the havoc they have wrought.

I was on a radio show after the ballgame last night and today the guys were kidding me about the gift. In the majors it's usually something worth $25 or $50, but in the minors it's a choice: You can have a "best wishes for the rest of the year" or an "everybody's rooting for your comeback."

The news came this morning. "Hrrrmph," Marvin Milkes said, or words to that effect. I was back with the Seattle Pilots.

When I got to the clubhouse today it was as though I'd never left. It was fun being back with all the guys again, and I really laid my week in Hawaii on them.

Gary is a typical ballplayer in some ways in that he doesn't seem to have any plan for himself, nothing to fall back on. The day he's out of baseball is the day he'll start thinking about earning a living. And then it could be too late. We stayed up so late talking that I needed a nap in the bullpen. Fortunately the Minnesota bullpen is out of sight. So I slept four solid innings before going into the game. There may be better ways to earn a living, but I can't think of one.

Today Joe Schultz said, "Hey, I want to see some el strikos thrown around here."

I'm always fascinated by what people say during infield practice. It's a true nonlanguage, specifically created not to say anything. This one today from Frank Crosetti as he hit grounders: "Hey, the old shillelagh!"

Eddie O'Brien has finally been nicknamed. "Mr. Small Stuff." It's because of his attention to detail. Says Mr. Small Stuff, "Put your hat on." He said that to me today. Also to Mike Hegan. We were both running laps at the time.

Oh yes. As I went out to pitch he said, "Throw strikes." I don't think Eddie O'Brien understands this game.

This afternoon Gary Bell and I hired a car and drove up to the Berkeley campus and walked around and listened to speeches—Arab kids arguing about the Arab-Israeli war, Black Panthers talking about Huey Newton and the usual little old ladies in tennis shoes talking about God. Compared with the way everybody was dressed Gary and I must have looked like a couple of narcs.

This afternoon Gary Bell and I hired a car and drove up to the Berkeley campus and walked around and listened to speeches—Arab kids arguing about the Arab-Israeli war, Black Panthers talking about Huey Newton and the usual little old ladies in tennis shoes talking about God. Compared with the way everybody was dressed Gary and I must have looked like a couple of narcs. So some of these people look odd, but you have to think that anybody who goes through life thinking only of himself with the kinds of things that are going on in this country and Vietnam, well, he's the odd one.

So they wear long hair and sandals and have dirty feet. I can understand why. It's a badge, a sign they are different from people who don't care. So I wanted to tell everybody, "Look, I'm with you, baby. I understand. Underneath my haircut I really understand that you're doing the right thing."

Gary Bell and I have become the Falstaffs of the back of the bus. Gary entertains with quotes, anecdotes and insults, and when he goes back to his real-estate book I do my routines. In a trivia game recently I asked who the moderator of "You Asked For It" was. The answer was Art Baker, which led me into my "You Asked For It" routine. "We have a letter from a listener, Mrs. Sadie Thompson of Jablib, Wisconsin. "Mrs. Thompson writes: 'Dear Art, I've always wanted to see a cobra strike an eighty-year-old lady. I wonder if you can arrange this on your show.' "Yes, Sadie Thompson out there in Jablib, we went all the way to India for you and not only did we get a cobra, we got a bushmaster, the most deadly snake in the world. And right before your eyes the snake will be placed into a glass cage with sweet little white-haired Mrs. Irma Smedley. Here comes the snake into the cage, and just look at that sweet little old lady tremble. The snake strikes and that's it, ladies and gentlemen, the end of Mrs. Irma Smedley. Remember now, it's all because you asked for it." The boys ate it up. Sick humor is very big in the back of baseball buses and "You Asked For It" is almost as good as "Obituaries You Would Like To Read." Tune in next week, folks.

One of the favorite back-of-the-bus games is insulting each other's wives, sisters, mothers and girlfriends. Some of the guys, among them Brabender and Marshall, refuse to participate in this game, but sometimes they're in it anyway. That's because any man who laughs when another man's wife or mother is insulted is automatically chosen as the next victim. Back-of-the-bus is a very rough business.

Before the game with the Red Sox tonight, we terrified pitchers huddled together and whispered about the power that club has. We decided that if Fenway Park in Boston is called "friendly," then the stadium here would have to be considered downright chummy. After the pitchers took batting practice, we were wondering if we should stay in the dugout and watch the Red Sox hit. We decided it would not be a good thing for us to see. We saw enough in the game. They beat us 12-2.

I came in with two runners on and stranded them and had a perfect inning-and-a-third. Then Brandon, Aker and Segui were stomped. So I should be back on the top of the heap again. Baseball isn't such a funny game.

Warming up in the bullpen tonight I got back the good knuckler, the one I had last year. They moved like a bee after honey, and I was throwing them real hard. Haney was catching and he said, rubbing a knee, that he'd never seen anything like it. "If you can just get someone to catch you," Haney said, "you'll be all right."

Mike has some interesting ideas on what kinds of pitches should be thrown. He thinks a completely random pattern is best, that the hitter should never have an inkling of what's coming next. As a result, if a guy gets a hit off a curve ball he may get a curve the very next time up. On the other hand, McNertney believes that if you get a guy out on fastballs, you keep throwing him fastballs until he proves to you he can hit them. As for me, I throw the knuckleball.

Incidentally, the pitching staff was happy to learn tonight that Marvin Milkes had stationed a man outside the ballpark to measure the home runs that the Senators hit out of sight. Instead Marshall threw his two-hitter. Take that, Marvin Milkes.

Joe Schultz called me over and I thought he wanted to talk about my knuckleball, or pitching in general, or perhaps the state of the nation. Instead, with a straight face, he asked me whether I had any light-colored sweatshirts or did I have only the dark kind I was wearing. I told him I had about fifteen dark sweatshirts since the other clubs I had been with all had dark blue sweatshirts. I said I used the dark ones in practice before the game, then changed to the Pilots' light blue for the game. He considered that for a while, then finally nodded and said, "I guess that's okay." Joe Schultz has yet to say a word to me about my knuckleball. Not even, "I guess that's okay."

During the game the public-address announcer explained where to pick up the ballots to vote for "your favorite Pilot." I thought it necessary to remind the people sitting near the bullpen that your favorite Pilot did not necessarily have to be good.

The first thing I felt when the Yankees showed up at the park today was embarrassment. That's because our uniforms look so silly with that technicolor gingerbread all over them. The Yankee uniforms, even their gray traveling uniforms, are beautiful in their simplicity. John O'Donoghue said that when Johnny Blanchard was traded to Kansas City he refused to come out of the dugout wearing that green and gold uniform. I would guess it's the only feeling I've ever had in common with Blanchard.

Then the game. It was fantastic, unbelievable and altogether splendid. We scored seven runs in the first inning and made them look like a high school team. They threw to the wrong bases. Their uniforms looked great; they looked terrible. It reached the point where we were going nuts in the bullpen, jumping up and down and screaming and hollering. And suddenly I wasn't embarrassed by my uniform, I was embarrassed for the Yankees. They looked so terrible. Cheez, I wanted to beat them bad, but this was ridiculous. Seven runs. I wound up telling the guys to sit down and cool it.

I was very careful to keep a big smile on my face when I reached the scene of action. I didn't want anybody to think I was angry or serious. By and large nobody is serious about these baseball fights, except the two guys who start them. Everyone else tries to pull them apart and before long you've got twenty or thirty guys mostly just pulling and shoving each other. The two guys who started it have so many guys piled on top of them they couldn't reach for a subway token, much less fight. At the bottom of the pile Murcer and Oyler found themselves pinned motionless, nose to nose. "Ray, I'm sorry," Murcer said. "I lost my head." "That's okay," Oyler said. "Now how about getting off me, you're crushin' my leg." "I would," Murcer said, "but I can't move."

I sort of circled the perimeter of action with both arms out to fend off any blind-siders and here came Fritz running toward me. He was laughing his head off and we grabbed each other and started waltzing like a couple of bears. He tried to throw me off balance and I tried to wrestle him down and all the time we were kidding each other. "How's your wife?" I said. "Give me a fake punch to the ribs." "She's fine," he said. "You can punch me in the stomach. Not too hard." Finally he got me down and we started rolling around. Two umpires came running over and told us to break it up. "But we're only kidding," I said, protesting. "We're old roommates." "Break it up anyway," the umpire said. Which made me think that here are two of four umpires breaking up a playful little wrestling match while there's a war going on nearby with 40 guys piled on each other. I guess they both recognized that they were in a very safe place.

The most interesting thing about the fight was Houk's reaction to the police, who came on the field to break it up. When he saw them he went out of his skull. "What the hell are cops doing on the field?" he shouted. "I've never seen cops on the field before. They ought to be at the university where they belong." What he didn't understand, of course, is that the very thing that made him angry at the sight of cops is the same thing that puts kids uptight seeing them on campus.

I'm a terrible hitter in batting practice, possibly because I'm a terrible hitter in games. I'm so bad they call me Cancer Bat, and when they made up the teams I was, naturally, thrown in at the end. When one of the guys on the other team complained that Bell's team had all the good hitters, he said, "Whaddayamean? We got Bouton." That seemed to mollify the opposition.

An outfield game is making up singer-and-actor baseball teams purely on the sound of their names. Example—Panamanian. Good speed, great arm, temperamental: shortstop Jose Greco. Or big hard-hitting first baseman; strong, silent type: Vaughn Monroe. And centerfielder, showboat, spends all his money on cars, big ladies man, flashy dresser, drives in 75 runs a year, none of them in the clutch: Duke Ellington. Finally—great pitcher, 20-game winner five years in a row, class guy, friendly with writers and fans alike; stuff is good, not overpowering, but he's smart, has great control and curve ball, moves the ball around: Nat King Cole. If you think this is a silly game, you haven't stood around in the outfield much.

Today I've been thinking about God and baseball, or is it baseball and God? In any case, this rumination was caused by the sight of Lindy McDaniel of the Yankees. Although I've never met him, I feel I know him pretty well because of this newsletter he sends out from Baytown, Texas, called "Pitching for the Master." One of the first I got from him—and all the players receive them—was a complete four-page explanation of why the Church of Christ was the only true church. The dogmatism of this leads to the kind of thinking you find in the Fellowship of Christian Athletes and in Guideposts and The Reader's Digest. The philosophy here is that religion is the reason an athlete is good at what he does. "My faith in God is what made me come back." Or "I knew Jesus was in my corner." Since no one ever has an article saying, "God didn't help me" or "It's my muscles, not Jesus," kids pretty soon get the idea that Jesus helps all athletes and the ones who don't speak up are just shy or embarrassed. So I've been tempted sometimes to say into a microphone that I feel I won tonight because I don't believe in God. I mean, just for the sake of balance, to let the kids know that belief in a deity or "Pitching for the Master" is not one of the criteria for major-league success. But I guess I never will.

Tonight I was making some notes in the bullpen and Eddie O'Brien was slowly going out of his mind with curiosity. Finally he sneaked over and snatched the paper out of my hand. I snatched it right back. That's all Mr. Small has to find out—that I'm writing a book. It'll be all over for the kid.

Today Mr. Small came out to the outfield where the pitchers were running and said, "Gentlemen, from now on we can all run with our hats off. It's really silly for us to run with our hats on, because the band gets all sweaty and ruins the hat." "How come you weren't able to think of that a few weeks ago?" I asked him. "Well, it wasn't as warm then and we weren't sweating at the same rate we are now." Oh.

We've been running short of greenies. We don't get them from the trainer, because greenies are against club policy. So we get them from players on other teams who have friends who are doctors, or friends who know where to get greenies. One of our lads is going to have a bunch of greenies mailed to him by some of the guys on the Red Sox. And to think you can spend five years in jail for giving your friend a marijuana cigarette.

On the way to the ballpark tonight Ray Oyler, sitting in the back of the bus during a bumpy ride, discovered an erection. He promptly offered to buy the bus from the driver.

Jose Cardenal was in center field fixing the legs of his tight pants and Talbot recalled the time in winter ball when Cardenal refused to play for three days because his uniform wasn't tight enough.

Back at the hotel, Gary and I talked about the relationship between country and city guys on a ballclub, which is intertwined with the relationship between whites and blacks. There are lots of walls built up between people, and I pointed out that if I'd never roomed with Gary I would still think, "Oh, he's just a dumb Southerner." So probably the solution is to have people live together. I mean we still disagree about a lot of things—religion, politics, how children should be raised—but because we've been able to talk about these differences, spend so many hours together, we've been able to at least understand them. How's that for a solution? Put people together in a hotel room in Cleveland.

I tried to let Joe know that I haven't been pitching much lately. "I sure could use a workout," I said. And Joe Schultz said, "If you need a workout go down to a whorehouse."

What it all boils down to is money. If I get a raise next season we could afford to do any of these things. But if I have a bad season and they don't like this book, I may not even get a contract. So we decided that what I probably should do is get them to give me a contract at the end of this season, before they know about the book.

Joe Schultz was put away by Earl Weaver of the Orioles tonight. We had a two-run rally going when Weaver came out of the dugout and pointed out that we were hitting out of order. Seems that Joe had made out two lineup cards and given the umpires the wrong one. Weaver, who spotted it right away, let us hit until we got something going and then we had to call it all back. Since we lost the game 9-5, and since there was no telling how many runs we might have scored that inning, Joe's face was very red indeed. I don't think he'll be telling us to keep our heads in the game again very soon.

Before we left the park today we were told that tomorrow's game would start at twelve-fifteen because of national television and that we'd have to take batting practice at ten-thirty. "Ten-thirty?" said Pagliaroni. "I'm not even done throwing up at that hour."

Tony Kubek and Mickey Mantle were here to do the TV broadcast and before the game Mickey was down in the clubhouse. With me standing right there, Joe Schultz says, "Mickey, what do you think of a guy who comes to the ballpark fifteen minutes before the game starts?" Mickey shook his head sadly. "I know he's got some strange ideas," he said.

Don Mincher was worried about appearing on national television. "My mother's going to watch this ballgame in Alabama," he said, "and she's going to notice first thing that I'm not using the batting helmet with the earflap on it. And tonight she's going to be on the telephone, guaranteed, asking me why I'm not wearing my earflap."

There was also something about Fred Talbot. Fritz said that Talbot seemed to have changed a lot in the last year and that I'd probably like him now. I showed Talbot the letter and he said, "That son of a bitch. I thought he always liked me." I guess Fred is changing. The other day, after he won in Cleveland, I reminded him that he'd already matched last year's output of wins (one). A couple of years ago he'd have gotten angry. Now he just laughed.

The latest adventure of Mike Marshall has him feuding with Sal Maglie about his screwball. A screwball is a curve ball that breaks in the opposite direction of a curve ball: When thrown by a right-handed pitcher it breaks in on a right-handed hitter. Mike wants to throw screwballs and Sal wants him to throw curve balls, so they're at each other all the time. "Why don't you just throw screwballs and tell Sal they were curve balls?" I suggested. "I would," Marshall said. "But then the catchers tell Sal what I'm throwing." See, the catchers are angry at him for trying to call his own game. So they go back to the bench and commiserate with Sal when he complains about the way Marshall is pitching. Mike won fifteen games last year and until recently he's been our most effective pitcher. They haven't disproved any of his theories. Why can't they just leave him alone? I'm afraid Mike's problem is that he's too intelligent and has had too much education. It's like in the army. When a sergeant found out that a private had been to college he immediately assumed he couldn't be a good soldier. Right away it was "There's your college boy for you," and "I wonder what our genius has to say about that?" This is the same kind of remark Sal and Joe make about Marshall. I think Sal and Joe put me right up there with Marshall in the weirdo department. They don't believe that my kind of guy can do the job, so when I am successful they're surprised. When Fred Talbot does the job, well, he's from the old school, blood and guts, spit a little tobacco juice on it. Another thing. When I was winning a lot of ball games my double warm-up was a great idea, an innovation, maybe even a breakthrough. After I hurt my arm, the double warm-up became a terrible idea. It was sapping my strength. In fact it was downright weird.

In the clubhouse Joe delivered his usual speech: "Attaway to stomp 'em. Stomp the piss out of 'em. Stomp 'em when they're down. Kick 'em and stomp 'em." And: "Attaway to go boys. Pound that ol' Budweiser into you and go get them tomorrow." This stuff really lays us in the aisles.

Jerry Neudecker was the umpire at third base. His position is just a few steps away from our bullpen and he stopped by, as umpires will, to pass the time between innings. "Why is it that they boo me when I call a foul ball correctly and they applaud the starting pitcher when he gets taken out of the ballgame?" says Neudecker. Says I: "Because, Jerry, the fans recognize the pitcher as being a basically good person." He laughed. Actually I think umpires can be too sensitive. They have this thing about a word. You'd think it was sticks and stones. The word is motherfucker and it's called the Magic Word. Say it and you're out of the game. I have only one question. Why? Now think about that.

Talbot is in rare form these days. Like he was telling us how it used to be in the sheet-metal shop of the industrial school he went to. When they were taught how to weld, the first thing they did was weld the door shut when the teacher left the room.