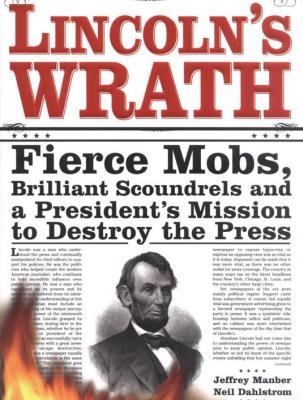

Lincoln's Wrath: Fierce Mobs, Brilliant Scoundrels and a President's Mission to Destroy the Press

Jeffrey Manber and Neil Dahlstrom (2006)

By the summer of 1861, a new type of article had appeared: reports of newspaper suppression and censorship, public or political malevolence, and individual attacks against those responsible. Most of the newspaper articles at the onset of the war carried no byline. Correspondents who were unknown to the readership wrote stories, and editors wanted it that way. Writers who did sign their work used false names or initials to protect themselves from physical retribution for their usual scathing attacks. This would change later, as Union generals demanded greater accountability from war-front coverage. Unwittingly, the era of the star reporter was born from the military concerns of battlefield coverage. (66-7)

Confronted with the threat of Maryland's legislature calling a second state convention that might lead to secession, Lincoln moved decisively. The president directed General Winfield Scott to be prepared for a vote on Maryland's secession, and should a move be made in this direction "to adopt the most prompt, and efficient means to counteract, even, if necessary, to the bombardment of their cities." Their cities. The president was speaking of a loyal state, not one that had left the Union, though his opinions toward Maryland were clear. (79)

Early in his administration and even before, the president argued that he stood squarely behind the rights of the press to freely publish their opinions. The president's recent actions in allowing a chill to settle over many traditional American freedoms, however, spoke louder than words. (110)

The New York resolutions not only conveyed the basic fears of Democratic editors, but also initiated a united front, a call to publicly take on the commander in chief and anyone working through his administration to crush the "friends of free institutions." Several factors had been identified. First, the publishers and editors were concerned that Lincoln was trying to fashion a consolidated system of government. Second, from the perspective of the Democrats, this evolution was contrary to the concept of a united government of independent states, functioning in voluntary association to create a more perfect union. (113)

Soon there would be a long grocery list of papers that could be singled out, from Maine to Maryland to Missouri to Illinois. But let us stop for a moment and consider with an unprejudiced eye the crime of this Connecticut paper. Why were fellow Democratic editors concerned for the safety of the editor and the future of the paper? What was the crime for which Republican editors were so angry? According to acconts, the Bridgeport Farmer had been targeted for "speaking of President Lincoln as a despot, and for accusing him of using despotic powers, or in other words, powers not delegated to him by the Constitution of the United States."

Republicans were shocked at this sort of criticism, not because it was false, but because it was a time of war, and dissension should not be tolerated. Here was a newspaper calling the president of the United States a despot and, especially after its army had just been embarrassed on the field of battle, such rhetoric could not be tolerated. The mob, the Farmer was warned, would arrive soon.

Editorials in Democratic newspapers argued that if there was illegality in their words, then why did they not "complain of it to the U.S. district attorney, who is a Republican, and one of the president's officials, and put the question to the test by a criminal prosecution?

The answer was ironically simple. Republican papers had been guilty of the same "crime" just one year before, when in anger over the policies of then-president Buchanan they unleashed a storm of criticisms against the president of the United States. Of course, Buchanan was a Democrat and as such was fair game for the Republican papers. With the roles reversed, why should it be different with a Republican in office?

The answer, they pressed over and over again, was incontrovertible: the country was at war.

The Bridgeport Farmer saw trouble in late July and early August, and was, as warned, destroyed by mob on August 24. (114-15)

The Confiscation Act, passed in early August with Hickman's help, gave local officials a new weapon: presidential endorsement. A battle to win over the average American to a new era of suppression was now underway. (116)

For the first time in our country's history, an administration unleashed the full power of the government to shut down opposition newspapers. (118)

On Friday, August 23, 1861, the Jeffersonian was closed not by an angry mob, but rather the administration of Abraham Lincoln. Now the question becomes far more realistic. Were these federal marshals acting with the permission of the cabinet? From how far inside the Executive Mansion came the authority to "take, hold, and keep possession of the building" that published the antiwar, anti-Lincoln newspaper? That was now a very appropriate question.

In the normal course of exploring a singular moment in the history of the Civil War one might expect that the involvement of the president in a particular event would forever remain a mystery. Especially in the nineteenth century, when so many political decisions were made informally, without the paper trails of more recent administrations. Was the president involved in the federal marshals taking control of the Jeffersonian? What do we know?

Well, we know exactly what the Hodgsons knew. The document handed to them revealed that the takeover of the building and the suppression of the newspaper were being taken "upon the authority of the president of the United States." (160)

"Where be those who, twelve months ago, thought ‘honest Abe' the right man in the right place, and who denyed [sic] to the people the right to question his wisdom or his motives? Where now are those who, even six months ago, with bare-faced, shameless mendacity, persecuted and imprisoned the people, who did not believe either in this honesty or his capacity?" —John Hodgson, January 17, 1863

There was a structure in the harbor of Baltimore that brought to life the fears of the antiwar editors. Though conceived as a fort, it was transformed in the opening days of the Civil War into a prison—a place to house the men who opposed Lincoln and his war.

Rarely in American history have there been prisons like Fort McHenry in Baltimore and Fort Monroe in New York and a dozen more scattered through the Union. Through their gates passed the entire spectrum of American society of the 1860s, apparently united only in their ability to sway voters to turn against the conduct of the war. (161)

"Among the prisoners may be found representatives of every grade of society," wrote the author of the 1863 pamphlet Bastilles of the North. "Governors of state, foreign ministers, members of Congress and of different state legislatures, mayors and police commissioners...doctors, civil, naval, and military...mechanics (especially machinists and inventors, whom the government regards as a dangerous class); editors of newspapers, religious and political (Governments don't like them)..."

Those taken to these prisons were all the living embodiment of the power of the Confiscation Act. As explained by one prisoner, these men were referred to as "prisoners of state, a term happily hitherto unknown on this side of the Atlantic, the very sound of which instinctively carries us to Italy and Austria, or the blackest period in the history of France."

The Official Records of the War of the Rebellion document the correspondence, much of it confidential at the time, which triggered the wave of arrests that continued throughout the war. They exemplify the dire consequences of wartime opposition, and showed citizens that no one, from a country editor to a national politician, was exempt from the wrate of the government in wartime. Overall, it is estimated that more than twelve thousand arrests of noncombatant citizens were made during the Civil War. (162)

With Maryland's Democratic representatives now in prison, the legislature would be allowed to meet without fears of secession. And with the leading sympathetic newspaper editors now confined at Fort McHenry, the city seemed suddenly very quiet. Meanwhile, the victims waited. None had been charged with a crime nor served with a warrant. (175)

While family, friends, and colleagues wrote furiously to state and federal officials petitioning for the release of the prisoners, Lincoln at last responded. His medium, as was his tendency on matters of such importance, was a loyal newspaper: this time the Baltimore American. The president took responsibility for the wave of arrests occurring in Maryland, but told citizens that they were on a need-to-know basis. "The public safety renders it necessary that the grounds of these arrests should at present be withheld," he wrote, "but at the proper time they will be made public." (176)

. . . an exchange of conversation said to have taken place between men seeking the release of a Fort Lafayette prisoner. Seward abruptly replied that the prisoner would not be released. The brother of the prisoner asked what the charges were, adding that there were no charges on him on file.

"Seward answered hastily: `I don't care a d--n whether they are guilty or innocent. I saved Maryland by similar arrests, and so I mean to hold Kentucky.' Then (Seward) turned on his guests; `Why the hell are you not at home fighting traitors, instead of seeking their release here?'" (188)

[James W.] Wall stood on a small podium that had been built in front of the house, the stone porch its base, and addressed the crowd. "What a study in contrast to the melancholy scene," he began after thanking the crowd, "hardly a fortnight ago, when I was dragged ruthlessly from these steps, torn mercilessly from the clinging embraces of the dear ones at home, and consigned to the tender mercies of the brutal military despotism that rules with iron sway within the gloomy walls of the American Bastille. I have been imprisoned for two weeks, against my will, and I have not been able to learn what these charges are.

"If by a simple mandate of any cabinet officer, in a state loyal to the Union as this has been, and when the courts of law are open, you or I may be torn from our homes, without cause shown, and consigned to the gloomy walls of a government fortress, the same mandate, only altered in its phraseology, may deprive us of our properties (or send us to the executioner), confiscating the rights of the states.

"The right to have our lives secure against interference and unreasonable searches is guaranteed." (189)

On Thursday, January 1, 1863, Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation came into effect. Born out of the apparent Union victory at Antietam, the Proclamation legally did not free any slaves, but it did create a moral and nobler justification for the war. It was now a war for liberation. From this day forward, when the federal army marched through Southern towns, they would bring with them the hope of freedom, a more tangible cause than the political struggle of the federal government to suppress the right of a state to break away. (205)

Ohio's Democratic congressman, Samuel S. Cox, warned that soldiers from his state would not fight "if the result shall be flight and movement of the black race by millions northward." Attempts by several entrepreneurs to bring freed blacks north sparked rioting and violence in southern Indiana and in Cincinnati, Ohio. (207)

And it was not just the men in the trenches who were less than enthused. General Henry Halleck dryly commented in a backhanded complement to Horace Greeley, "the conflict is now a damned Tribune abolition war." (208)

Courtrooms did not yet possess the noble grandeur of the later court. Judges did not dress in the formal black robe: it was not adopted until the 1880s. Courtrooms were not formal palaces reminiscent of Greek and Roman architecture, but were dark, small offices created in available space. The location of the courts [...] was more important than the physical buildings themselves. Most attorneys resided within walking distance, their homes doubling as their offices. (225)

For Democrats, they were fighting for the Constitution and the right to openly criticize the war, the president, and the centralization of power in the hands of what they saw as corrupt politicians taking personal advantage of the war. (251)

"We caution Democrats about using the term nation. The United States are not a nation, but a union. Jefferson, the Father of the Democratic Party, never used the word nation or national—it was the Union, the federal or general government, the Republic. It would be well for editors of papers, speakers, writers, and public men to return to the old time-honored terms. Nation means now a consolidated abolition, military despotism." —John Hodgson, April 11, 1863

[T]he private secretary for Lincoln wrote, astonishingly, in praise of the riots in New York against the draft. John Hay, giving his true thoughts privately in his diary, praised the riots as helping defeat the doctrine of states' rights. "I thank God for the riot if as one of its results we set a great authoritative precedent of the absolute supremacy of the national power, military and civil, over the state."

On this battlefield, which would continue long after the war was over, the Republicans were winning against their Jeffersonian Democrats. No single court victory would change the rising tide of federal power put into motion by Abraham Lincoln. (294)

It is said that little can be added to the examination of Abraham Lincoln. The body of literature suggests otherwise regarding the suppression of antiwar newspapers. When the issue is discussed in a secondary sort of manner, Abraham Lincoln has emerged unscathed by the verdict of most historians. Many ignore the issue, but those who do[n't] forgive him or excuse his actions. (299)

Through the end of the war, the Jeffersonian refused to tone down its columns. It was reported that the only newspaper in the state of Pennsylvania not to mourn the death of President Lincoln was the Jeffersonian. Hodgson displayed no flag, despite a general call made by the mayor of Philadelphia. Even the Age printed gracious words for the fallen president. Not Hodgson. (304)

|