Burning Book: A Visual History of Burning Man

Jessica Bruder (2007)

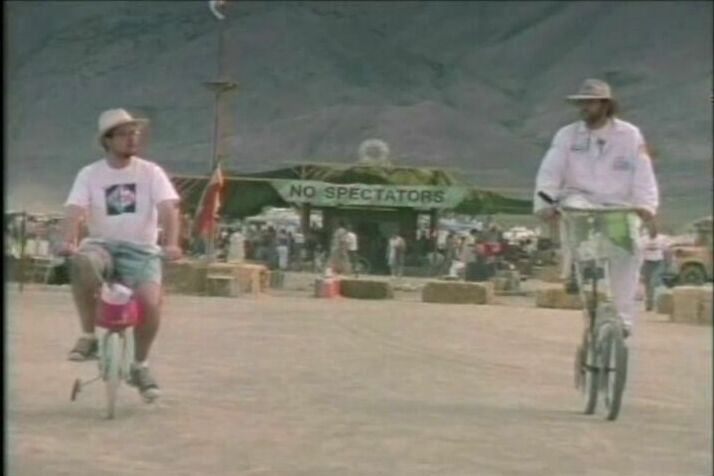

So why do the pilgrims, in growing numbers, still journey to that bleak desert? They go because the burning Man—a one-ton monument in flames—isn't the whole of Burning Man. At best, the Man is a vaguely coherent ambassador for everything else that happens in the five square miles around him, the area known as Black Rock City. This settlement—a place that writer Stephen Black once called, with admirable precision, an "Ephemeropolis"—requires the work of their own hands. They fill the desert with a staggering variety of art and amusements, gatherings, and performances, and when the week is over, they scour the dust to make it all disappear. The festival runs on a simple credo: "No Spectators." To put it plainly, the city is the work of the people who live there. If everyone came to sit back and absorb the culture, there would be nothing for them to see. (xi)

Since thousands of people are enacting their own visions of what Burning Man ought to be, Black Rock City is inherently plural and constantly changing. (xii)

The gambling halls of Reno, like most casinos, don't have windows. There are no cues to distinguish day from night, nothing but the constant rhythm of slot machines—bells chiming, quarters hailing down on chrome—to mark time. Still, the casinos, decorated in gaudy circus and Western themes, have cheap rooms and even cheaper food. That's enough to pull Burning Man pilgrims through the doors. They drag duffel bags still coated in stubborn dust from last year's trip to the desert. They pass the game tables and disappear into the elevators up to the rented suites without a backward glance. (2)

[SIDE NOTE: That sounds strikingly like a newspaper description of visitors to The Mojave Phone Booth: "Waiting in the casino lobby, the Phone Boothers look like they're from another planet. They seem strangely ecstatic and alive, whooping and cracking jokes to the unamused staff. [...] It's the sound of money, the wonderful and never-ending siren song of the casino. A siren song that doesn't touch [them]."]

Don Lawson, who is forty-four years old and grew up in Reno, has been encountering burners since he began running the Empire Store in 1995. "When it first got started, I used to call it my thirteenth month," he says. "It got to the point where it was an extra month's worth of business." Now Burning Man generates up to a fifth of his annual sales. . . . Don and his staff have to hustle to keep up with the shoppers, but he says they enjoy it. "It's one of the few times I allow drinking on the job," he declares. "We have a keg tapped in the garage, and it helps with the madness." (24-5)

In the following years they [the San Francisco Cacophony Society] toured the Oakland sewer system, rode a cable car naked, and scaled the Golden Gate Bridge. They launched an annual treasure hunt during the Chinese New Year parade that ended in a pie fight. The most daring adventurers staged a number of "infiltrations," posing as prospective members to probe the Moonies and the American Nazi Party. Suicide Club initiates also infiltrated the National Speleological Society but found they enjoyed caving expeditions too much to keep up the ruse and befriended the explorers instead. (58)

At the start of Labor Day weekend in 1990, around eighty friends assembled near a baseball diamond in Golden Gate Park. They loaded up a Ryder truck with sleeping bags, tents and the Man. By the time they set off in a caravan across the Sierra Nevada, it was already after dark. They reached Gerlach at dawn and stopped at Bruno's for breakfast, then continued onward. The procession stopped at the edge of the Black Rock Desert. Folks tumbled out of their cars. Michael Michael drew a line in the dust and pronounced, "On the other side of this line, everything will be different. Reality itself will change." Everybody held hands. Together they stepped across the line. (61)

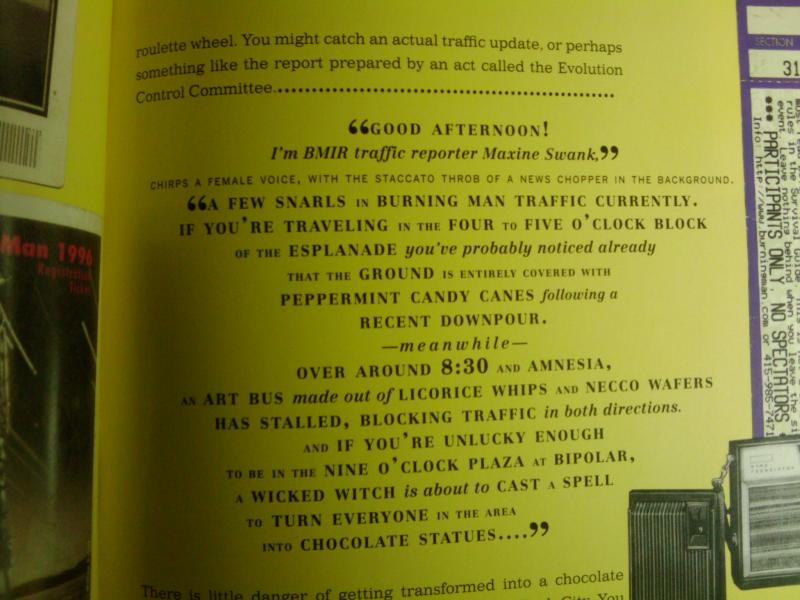

Fiddling with your radio dial is like spinning a roulette wheel. You might catch an actual traffic update, or perhaps something like the report prepared by an act called the Evolution Control Committee:

(68-71)

In the early days of Burning Man, one clever saboteur revised a NO SPECTATORS banner to read NOSE TATORS. That phrase entered the local vernacular; it evokes nostril plugged with playa dust. (81)

For the most part, the only logos you'll see are satire. The newspaper Piss Clear is full of fake ads that riff on the real thing, inviting you to buy a game called Grand Theft Artcar, or shop at Playazon.com. (97)

It's worth noting that, volunteer peacekeepers aside, there are plenty of genuine police at Burning Man, including federal ranges from the Bureau of Land Management and officers representing the State of Nevada and local counties. Undercover cops prowl for drugs, and openly smoking a joint could land you in handcuffs. The officers also intervene in rare episodes of violence, though Dave Cooper, who manages the area for the federal Bureau of Land Management, says of Black Rock City, "My perception is it's one of the safest places you could ever be. It's certainly safer than being in any other city of 40,000 people." In 2006 there were six arrests and 157 citations issued at the festival; 80 of the citations went to burners found with illegal substances. (133)

[At Thunderdome, a] guy took an upward kick in the groin so hard that he had to spend a few days in Reno, getting a bit of his anatomy surgically extracted. The Death Guild coined a descriptive cheer for him: "Two balls enter; one ball leaves." (168)

Food is a popular gift, but its popularity can cause problems. The Tuna Guys have found trouble on the playa since 2000, when officials from the Nevada health department shut them down, demanding to see a food service permit. Since then, the Tuna Guys have kept a low profile. To keep from violating state law, they must cook for special events and camp members only.

"We didn't violate any rules," Jim says impishly. "Although there was quite a few people who claimed to be camp members." In other words, the Tuna Guys' camp turned into a seafood speakeasy. (237)

Most burners use costumes to create new identities, but a few people focus on disguising their old ones. When Joan Baez went to Burning Man in 2005, she spent most days incognito, with an orange scarf wrapped around her head. This also made it easier to decline solicitations, including one from a gentleman who offered to whip her. Of course, there were moments when the mask came off, like the time she posed for a picture, licking the face of a life-size representation of President Bush, clad in a soaked and somewhat transparent slip (she'd been chasing a water truck). (270)

In early September, when the festival has just ended, there's a list that often makes the rounds by e-mail. Anonymously composed a few years ago, it's called "How to Experience Burning Man in the Comfort of Your Own Home." People keep adding to it. The list includes such suggestions as:

Stack all your fans in one corner of your living room. Turn them on full. Dump a vacuum cleaner bag in front of them.

Set up a DJ system downwind of a 3-alarm fire. Play a short loop of drum 'n' bass until the embers are cold.

Sprinkle dirty sand in all your food.

Spend thousands of dollars on a deeply personal artwork. Hide it in a funhouse. Blow it up.

Throw a sprawling, drunken, week-long party. Spend the next five weeks meticulously cleaning every square inch of your house. (333)

|