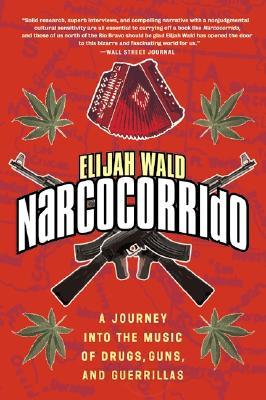

Narcocorrido: A Journey Into the Music of Drugs, Guns, and Guerrillas

Elijah Wald (2001)

Despite their successes, many feel underappreciated, both by the corrido fans who know their songs but not their names and by the intellectuals and writers who have dismissed their work as musica naca, music for hicks. (6)

As we drove on toward Parral, the country got steadily wilder, the hills higher and more jagged. On our right, the Sierra Madre beckoned me. Mexico's largest range, running from the Arizona-New Mexico border down toward Mexico City, it is the cradle of the Mexican drug trade, and the richest area for modern-day corrido heroes. Its steep mountains and deep valleys offer concealment for marijuana and opium fields, and for primitive landing strips where small planes can rest on the way from Colombia to the United States and pick up or drop off cargo. The mountain folk are famous for their toughness, their ability to walk long distances on little food or water, and their willingness to fight. Many of Mexico's most famous drug lords grew up running barefoot along the mountain paths, and entered the business as isolated growers before getting up their nerve to come down out of the hills. Illegal drugs have been a way of life here for decades, but have tended to be seen as a cash crop rather than a social ill. (25)

The chorus of the most famous of all Villista songs, "La Cucaracha" (The Cockroach), says that the cockroach cannot walk because he lacks marijuana to smoke. (27)

[Paulino Vargas:] "My culture is still very rough. I never went to school, and if you haven't studied you are just a little animal—if I don't bray, it's only because I can't get the tone right."

That final phrase is typical of Paulino's conversational style, simultaneously showing his modesty and his gift for humorous rhetoric, and he collapses in giggles, asking if I understand it. (33)

Paulino insists that a good corridista must also be a reporter: "When I have to make a corrido about someone, I go where the incident happened. I see something on the television, the radio, in the newspaper, and if the character interests me I make a trip and see how it was, what happened, to have some idea of what I'm going to say. I investigate the story. If there are relatives, I ask their permission, and if not I just shoot it out there without permission, but I have to be sure that it is factual. I don't like to invent things, it has to be true. You know, the public knows the difference, it can tell what isn't real and what is. It's a monster that you can't fool. For me, what works best is what's closest to the truth—although of course you have to add a bit of morbo."*

*Morbo is one of those quirky, untranslatable words. Literally, it means sickness unto death, but it can also mean a weird attraction ("she's ugly, but she has a certain morbo"), or a particular style of speaking, a twist one gives to language. (35)

We arrived in Mazatlan in the early evening, and I found a hotel near the beach and settled in for a few days of rest and relaxation. I bought some books on the drug world, went to a couple of concerts, and hung out in the local record stores, absorbing music and conversation. The first thing I learned was that drug ballads here are simply called "corridos"; it would be tautological to append the "narco" prefix, since in Sinaloa there is no other corrido theme. (49)

Chalino has been dead for almost a decade, but his voice is heard from Sinaloa to Los Angeles. At least, it sounds like his voice. In the West Coast drug belt, the 1990s became the decade of the chalinitos, the little Chalinos, hundreds of young men trying to sing, dress, move, and live like their idol. The audience demand was there, and many became popular recording artists. In ten minutes, a record store owner in Culiacan showed me cassettes and CDs of twenty-five different chalinitos, from the obviously named Chalinillo to Chalino's friend Saul Viera, El Gavilancillo (the little Hawk), who was assassinated in 1997, and on and on. (84) [Cp. The -berto's Phenomenon]

The apogee of child corridista weirdness is Lolita Capilla, "La Bronca de Sonora," a little girl who is shown on her cassette covers wearing a white, frilly confirmation dress and holding an assault rifle. (87)

El As has nine albums on the market, but he says that only twelve or fifteen of the songs he has recorded are his own compositions. To him, it makes little difference whether a song was written by another writer as long as it is truthful and feels right to him. "I think that when a corrido is real, you can feel that. When it is fictitious it also can give a feeling, but it isn't the same. Me, everything that I compose is taken completely from real life. Because of that, I sing with enthusiasm, because I know that I am singing about something that really happened. A fictitious corrido, I don't feel the same way singing it, because I don't know whether it happened or not."

As for his choice of themes, he is simply following the tastes of his customers. "This singing thing is a job, like being a journalist, you might say. Someone pays me to make a corrido and I do it. Why not? To me, it's no crime, because it's my job. So if a drug trafficker comes to me, wants me to compose a corrido for him, I do it with pleasure. Sure, I always try to protect him, I say to him, 'Give me a nickname to use,' but a lot of them don't want that:

"'I want my own name!'

"'Oh, fine, it's your problem. I'll do it with your name.'"

El As laughs as he imitates the braggadocio of his customers. It is an odd business, this lust to be immortalized in song, and I am reminded of a story Jose Alfredo told me: A law-abiding businessman from Los Mochis, the owner of a printing shop, sent over an assistant to commission a narcocorrido saying that he was a powerful traficante and had fought a great battle in which all of his employees died (he provided a list of names) and he was the only survivor. Now the song is a local hit, the printer's name has become notorious, and Jose Alfredo says, "If I told them that he's just the owner of a printing shop, nobody would believe me."

El As found this very funny, but added that it is no longer necessary for a corrido to be about desperate characters, or full of gun battles: "You can write a corrido for a mason, a journalist, for whoever you want. Whoever asks for a corrido, I write him one; he doesn't have to have killed someone or to be a drug trafficker. To make a corrido, all I need is when you were born, the names of your parents, what your work is, or what you do with yourself, where you're from, the name of your town and with that the corrido is done, just as easy as that. That is, you don't necessarily have to go around running trailers stuffed with mota [marijuana]." (93-4)

The rides came easily until south of Guamuchil, where I got stuck for about an hour. Finally a bus pulled over, and I thought what the hell and climbed aboard. As it turned out, the driver had picked me up as a hitchhiker, not a passenger, and he declined to take my fare. One more thing to like about Sinaloa. (97)

Juan Carlos knew the club's manager, so I stowed my pack and guitar in the office and hunkered down for another long evening of women peeling down to bikinis over bad disco music, subpar ranchera singers and, this time, not even a ventriloquist to perk things up. The one interesting aspect of the situation was watching the men along the ramp, as they watched the ladies but kept running their hands over one another. Oscar, the painter, had pointed this out to me at El Quijote: a lot of the macho men seem to let out another side of their personality when there is enough alcohol, sex in the air, and no "decent" women around. One of the pobresores even had a go at me until Juan Carlos told him to lay off. (104)

More usually, though, what distinguishes Mario's writing is its lightness and humor. Another marijuana song, "El Para" (The Break), is the monologue of a guy taking a break from work to smoke some dope (which—presumably to protect the children—he refers to as "Martin") with his friends, and is full of lines like:

La policía la quema, también nosotros podemos;

Si ellos queman toneladas, nostoros quemamos leños

La culpa no es de nosotros que exista la hierba buena,

Porque aquí la combatimos, en manto llega se quema.

(The police burn it up, we can do the same;

If they burn tons, we burn joints.

It is not our fault that grass exists,

Because we are combating it here; as soon as it arrives it gets burned.) (108-9)

At Mexican outdoor concerts, it is usual for each group to have its own stage, which means there is no wait between acts. As each group ends its set, another starts up on the other side of the field, and the crowd surges across to the new site. The only problem with this arrangement is that if one wants to be up close to the headliners one has to stake out a position at their stage and thus miss whoever is playing before them. (111)

They made the deal then and there, but it fell apart over Pedro's choice of backing group. He had picked Los Rayantes del Valle, who had a Tigres-style accordion-and-saxophone lineup, and it turned out that Chalino detested saxophones. "He said that to me: 'Neither Los Tigres del Norte, nor any other musician who plays with that crooked whistle is going to record with me, never in my life.'" (136)

Meanwhile, he [Pedro Rivera] continued to record his own work, though at fifty-four he is old enough to be the father of most of his current artists and his work falls outside the normal contemporary spectrum: he is neither a garishly raw singer, a la Chalino, nor a rich, virtuoso stylist like the mainstream ranchera idols, neither the toughest of the tough nor the cleverest of the clever. Instead, he keeps covering the news, winning airplay through timeliness. In a sense, his songs are novelty numbers: they sell well in their moment, but no one expects them to be around for more than a few months, and he makes no effort to reissue them or keep them in stock. As he talked about his work, I found myself recalling the newspaperman's credo laid down by A. J. Liebling: "I can write better than anyone who can write faster than me, and faster than anyone who can write better." When he talks about his corrido of the assassination of Colosio, he says, "That happened at five in the afternoon, and by six I had finished the corrido. We recorded it the same night, and the next day, at one in the afternoon, it was already on the radio, and people went nuts." (137-8)

As it happened, it was the night of the Grammys, and I lay on the sagging bed and watched the recording industry parade its new fascination with "Latin" music. There was Jennifer Lopez in her fabulous dress (every Latino, but hardly any Anglo, knows that Lopez does not speak Spanish). . . . (150)

[Guillermo] Santiso is a major record company executive, but despite Fonovisa's consistently impressive sales figures, he still feels like an underdog in the US entertainment business. Watching the Grammy broadcast, I could imagine how angry he would be. At the meeting, he had blown up over Ricky Martin, comparing him to Desi Arnaz and saying "all he needs is a bunch of bananas on his head to make him the perfect Latin stereotype." In his view, the US Latin music scene is overwhelmingly dominated by Cubans, the only Latino immigrant group to be largely made up of its country's ruling elite rather than of poor, uneducated manual laborers. The Cubans look down on the Mexicans as peasants and consider their music a lot of hillbilly trash. Besides, Santiso added, "The Cubans hate Mexico because the Mexican government supported Castro, so they will never do anything to help our music or our culture."*

* Santiso went on to lead a Mexican boycott of the first Latin Grammys, saying that it was simply "a party for Sony and Emilio Estefan," the Miami record mafia. (152)

Not all the immigrant songs were tragic. There was also a broad strain of humor in songs like "Los Mexicanos que Hablan Ingles" (The Mexicans Who Speak English), and "Las Güeras de Califas" (The Blondes of California), and Los Tigres had latched onto this tradition from their earliest recordings. Their interest in the theme gained new impetus in 1977, when they hit with Jesse Armenta's "Vivan los Mojados" (Long Live the Wetbacks), a song that astutely mixed ethnic pride, social commentary, and rough comedy. On the one hand, it spoke of the difficult lives of illegal immigrants, on the other it proposed a tongue-in-cheek solution: each mojado could be given a gringuita to marry, and could get a divorce as soon as he had his green card. The song's most memorable verses speak of what would happen to the United States if the mojados decided not to come anymore: the crops would rot, the dance halls would close, and the girls would be inconsolable. (157-8)

Apparently, taxis are not allowed to pick up fares off the street in Phoenix. The taxi companies, explain that this is due to the danger to the drivers. No offense to the chamber of commerce, but if this is the fastest-growing city in the United States then there is a deep sickness afflicting the country. (168)

It is hard to believe that Julián [Garza] took off quite that fast, but even allowing for some exaggeration his early output was extraordinary. His style was a model of classicism, and his songs quickly caught the ear of the region's norteño stars, then overlapped from the radio and jukeboxes into local folklore. ("Oh yeah," Julián says. "Those songs were so popular, even the damn dogs were singing them.") (189)

"And one of the guys who fired comes past where I was, and handed me his gun: 'Take the gun, keep it for me.'

"'No, cabrón, how can you give me that gun? You'll just get me messed up in this crap. What does it have to do with me? Toss it to fuck your mother, or do whatever you want with it, why give it to me?' He wanted to get rid of the evidence of the crime, so of course I didn't take it. Are you nuts? How was I going to take the gun from that cabrón? So he ran off, he went up to the mountains."

So, I ask, did Julián write a corrido about the killing? His expression becomes serious: "No, those cabrónes killed each other like cowards. If they had been men, they would have gone out in the street, to the mountain, to kill each other. Those bastards killed each other with children around, that doesn't inspire me to write them a corrido."

But if they had gone outside?

"Ah, then I would have made them a corrido, of course. Let them go and kill each other like men, outdoors, among the mesquite plants y la chingada. Then, naturally, right there I would have written one." Julián is getting into the spirit of the thing, miming the action of scribbling on notepad. Then he shrugs and dismisses the gunmen. "But the way they killed each other didn't suit me." (191)

After a while, someone brings out a plastic bag of cocaine and invites me down to the bathroom at the foot of the yard to partake. I say no, I never liked coke because I like to eat and sleep, and why would I do a drug that takes away my appetite and keeps me awake? "Oh no," Julián says. ''You've been using that lousy stuff you get up there, cut with speed. This is very pure, it won't take away your appetite." Besides, the others point out, we will be hanging around drinking beer for hours, and this will keep me alert. When I consider the importance of thoroughly researching my theme, no more argument is needed, so the rest of the evening is punctuated by trips to the bathroom, where we snort coke off the ends of door keys, one sniff in each nostril. It works, too. I keep drinking beer and do not get drunk in the least. Anyway, that is how it seems at the time. My notes tell a different story, becoming progressively less legible as the evening wears on. (194-5)

My sense of time soon disappears, but at some point I find myself down there and Julián is standing beside me, asking a favor: during the previous day's interview, he had made a disparaging remark about the instrumental abilities of a famous norteño group, and he wants to be sure that I will not include it in my book. "No, Julián," I say, teasing him. "I'll just write about the cocaine."

"Oh, that's fine," he says, grinning. "No one cares about that. But those guys are my friends." (197)

Texas musicians all have stories about Salome Gutiérrez, in which he frequently figures as a more or less charming rogue. For instance, one musician told me of an all-night recording session during which Salome got the players drunk, then had them sign a stack of blank copyright forms—that way, if they ever got a hit song later in their careers, he could fill in the necessary information and claim he owned the original rights. In another story, a producer in California told me of getting a threatening letter from Salome, claiming that a song on the producer's latest release had been copyrighted by Salome's publishing house back in the 1960s. The documents Salome submitted seemed ironclad, until the producer noticed that they included Salome's telephone, address, and fax number. He got on the phone, and shouted, "Hey, there weren't any faxes back then!" Salome was pleasant and charming as ever: no harm in trying, and no hard feelings. (207-8)

October 2 is a key date in Mexican history, though it has only recently been added to school curriculums. In 1968, as student protests were bursting out all over the Western Hemisphere, Mexico City was hosting the Olympic Games. President Díaz Ordaz took great pride in being the first Latin American head of state to have this honor, and he was damned if a bunch of rowdy radicals was going to interfere with his crowning achievement. His attempts to beat down the protesters culminated in the massacre of Tlatelolco. On October 2, thousands of people gathered in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas, in the north central part of Mexico City. The army surrounded them with tanks, posted sharpshooters in the windows of adjoining buildings, and simply mowed them down. No one knows how many people died—the army hauled the bodies away in trucks and buried them secretly—but estimates run between three and five hundred. (216)

Gabriel [Villanueva] enjoys recalling one instance in particular: "This happened with a friend who got in a fight with another friend, and he beat the other guy, fighting with machetes. He gave his rival seven machetazos, and after he killed him, like fifteen days later, we ran into each other—someone else introduced us, he said, 'Look, this is the guy that killed so-and-so.' And he said to me, 'Yes, it was me, I gave him seven machetazos.'

"'No, well, that's fine. You were defending yourself, right?'

"And he says, 'Write me a corrido.'

"I said, 'I'll write it for you, but I assure you that the day that record comes out they'll take you prisoner.'

So I wrote the corrido, and about two months later the judiciales grabbed him, because of the corrido. Because if something is under cover and you shake the hive, the bees get stirred up, no? This kid didn't want to believe me, but the family of the guy who was killed heard the record or the cassette, they listened, and two months later the police grabbed him, and it seems he had to pay about fifteen thousand bills before they let him go. Afterward, he saw me and he said, 'It's true, Gabriel, what you told me.'" (242-3)

I tried to get more details out of Teodoro [Bello], such as whether he actually researched the song in newspaper archives, but he was not interested in following this line of questioning, so I moved on to "El General." This corrido tells a much more famous story: in February of 1977, General Jesús Gutiérrez Rebollo, who had been appointed the top drug-war liaison between Mexico and the United States, and whose integrity had been praised to the skies on both sides of the border, turned out to be in the pay of Amado Carrillo. (This story is the basis for a principal plotline in the film Traffic.) Gutierrez claimed that he had only accepted Carrillo's money as a way of getting into the drug lord's confidence, but no one believed him and he is now in prison. No one, that is, except Teodoro. His song gives the general the benefit of the doubt and focuses its attention on the fact that, however much corruption may exist in Mexico, the money that is paying all the bribes comes from up north. He drives his point home in the song's penultimate verse:

A diferentes países lo certifican los gringos;

No quieren que exista droga, pues dicen que es un peligro.

Diganme ¿quién certifica a los Estados Unidos?

(The gringos certify various countries,

They don't want drugs to exist, they say it is a danger:

Tell me, who certifies the United States?) (295)

|