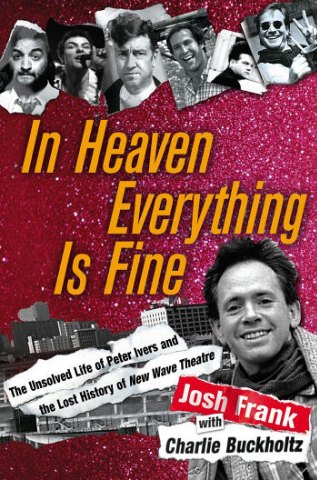

In Heaven Everything Is Fine: The Unsolved Life of Peter Ivers and the Lost History of New Wave Theatre

Josh Frank with Charlie Buckholtz (2008)

When we first spoke on the phone she [Lucy Fisher] said something that has stayed with me the entire time I worked on the book: "I have been dreading this day for a long time." It hit me then that this was not just a cool story based on five words in a weird movie I saw in high school. It was a responsibility far beyond any that I had undertaken before. This feeling was confirmed by what Lucy said next: "You have no idea what you're getting yourself into." (xvii)

The first person I spoke with after visiting Lucy was Steve Martin. (not the comedian, although this Steve Martin is also very funny). . . . Steve and I ended our evening, he said, "You're going to find out who this guy was and it's going to blow your mind. And it will make the loss of him that much more profound. " (xviii)

Paul Michael Glaser approaches the officers with a worried look. He has heard bad news about a good friend and would like to know where things stand. The scene he encounters is pandemonium and the police don't seem to be doing anything to create order, much less protect the peace. In fairness, the police are vastly outnumbered. But he would like, at least, to know what happened and if there is anything he can do.

Overwhelmed by the throng, losing once and for all whatever grasp of the situation they may have had, as the crowd crushes in around them, the two officers are hit with the full weight of the knowledge that they have no idea what this place is, who this person was, what it all means, or how to proceed. Glaser opens his mouth, but before he can get a question out, or even a word, one of the officers shouts his own question over the mob's raucous din.

"What do we do, Starsky?" (17)

A few weeks ago his fifth-grade teacher had called her in for a private conference. Swearing Merle to secrecy, the teacher pleaded with her to take Peter out of the public school system. If her advice were discovered it could mean losing her job, but she felt it would be the best thing Merle could ever do for her son. "There is no way I'm going to be able to keep him focused," she had said, "there is just not enough here to satisfy his thirst for knowledge." (23)

He would often tell people, "Cicero has the best rock lyrics if you can read them in the original." (29)

There was one nagging anxiety in his life. From the day the Harvard test crowned Peter a genius, his father's attitude towards him had changed. From Paul's perspective, being a genius carried with it certain responsibilities—in particular, academic excellence. Throughout high school, Peter excelled in the subjects that interested him and paid little attention to those that didn't. The first time Peter had brought home a C, in a high school math class, Paul took it as a personal betrayal and hung it on Peter like a scarlet letter for the rest of his high school career. "You have the IQ of a genius!" Paul had said, in what was to become the punishing refrain of their deteriorating relationship. (35)

Susan Stockard [Stockard Channing] was one of the few who knew where Peter had gone: to Chicago, to study and play blues harp with Muddy Waters.

This was precisely what made Peter different from the rest of the Mayer set. Sometimes, Cutler, Peter, and Mayer would go see Muddy Waters perform at Club 47. And whereas Mayer and Cutler would appreciate it deeply and expound on it for hours hence, Peter, upon the show's conclusion, would approach the bandstand and strike up a conversation with Waters—or little Walter, or Junior Wells, or whoever was being featured that night. He would ask them about their music and about their harp technique; he would ask them where they played when they were back home in Chicago. And then, one day towards the beginning of sophomore year, he'd decided to go and find them. (38)

"While I was looking for the right singer, I made a few demos with me singing. And people really liked the voice. It sounds like Howling Wolf, if he inhaled helium." (40)

[Cp: "Chester developed the howl that made him famous by listening to the first great country music star, Jimmie Rodgers, the 'yodeling singer.' 'I couldn't do no yodelin' so I turned to howlin'. And it's done me just fine.'" (From Moanin' at Midnight: The Life and Times of Howlin' Wolf by James Segrest and Mark Hoffman, quoting an interview by Barry Gifford in Rolling Stone, 24aug1968)]

HAROLD RAMIS: "That's what [the police] wanted to believe: that he was a hippie, punk, pervert, drug user who deserved what he got." (42)

DETECTIVE CLIFFORD SHEPARD: "Most of the time when you have a murder, the victims are doing something they shouldn't be doing, or involved in something. Not always, but a lot of our murders have victims involved in similar activities. It's a matter of lifestyle. " (42-3)

HAROLD RAMIS: "I learned secondhand that for the first weekend I was the number one suspect. They thought I had killed Peter because I was jealous. Very far from the truth. Even the jealousy thing. It was a mystery and a tragedy that the police couldn't solve." (44)

RICHARD GREENE, musician, collaborator, and friend: "They didn't do a damn thing. We were first on the scene, and we had all kinds of ideas and everything, and nothing was followed up. " (44)

Doug [Kenney] had not been happy to return for his sophomore year of college to find Kim, his erstwhile girlfriend, in love with Peter. Still, neither was about to let it get in the way of the friendship they had struck up the year before. It was not their brief history that kept the connection between them intact as much as a palpable sense of future potential, an intuition on both their parts of having found that rarest thing: a kindred spirit. (48)

Depending on the angle and the moment one caught a look at them, Peter and Doug could seem either an odd couple—an attraction of opposites—or a well-matched, set. Kim Brody was attracted to the same things in both of them: the boyish free spirits housing minds that were subtle and searching, continuously surprising, awesomely vast and vastly, awesomely offbeat. Chris Hart, who was friends with both, saw them as rarities and geniuses whose backgrounds, intellects, and jet-fueled imaginations rendered them perennial outsiders. They were both sentimental, empathic, and openhearted, though they could also be cutting, and did not suffer ignorance, intolerance, or any form of authority gladly. When [Tim] Mayer was around (he had become close friends with Kenney as well, and the three of them together were referred to in their circles as "the three musketeers"), they didn't suffer it at all. (48-9)

To Peter, underutilized potential was a tear in the fabric of the cosmos. He saw himself as an agent of repair, and did what he could to line up the seams. There was no clear line between being an artist, a catalyst, a collaborator, and a friend. (57)

HOWARD CUTLER: "The Lampoon is a source for The Simpsons [intrusive plug: not this The Simpsons], and Conan O'Brien. But it's a different generation now. The president, to give you some idea how that moves, the president of the Lampoon, a year or two before I got there, was the guy who's now Dr. Andrew Weil." (60)

Looking out over the small but devoted audience in the smoky room, Waters referred to Peter as "the greatest harp player alive."

For Peter, as for Waters, this praise must have come with a bittersweet edge. Earlier that year, Little Walter had died of head injuries sustained in a street fight. He was thirty-seven: If Peter were indeed the greatest harp player alive, he knew (and he knew Muddy knew) that it was only because Walter was no longer among the living. (70)

The first few times Larry Cohn met Peter Ivers, he did not remember his name and could not think of a reason in the world why he should. Peter was just another kid in a band that had made the pilrimage to his New York office in search of a contract. Peter—short, rosy-cheeked, and looking about twelve years old—hung back quietly while the bandleaders, Jim Kweskin and Mel Lyman, schmoozed with Cohn. (71)

Jim Kweskin's Jug Band had been one of the hottest groups to come out of the Boston folk revival, achieving national popularity and critical acclaim almost from its formation in 1963. Then, in 1968, just as they were breaking through to commercial success, Kweskin dissolved the band, shaved off the mustache that had become his trademark, and moved in with the Lyman Family, a commune that was widely thought of as a cult in a run-down neighborhood in Boston.

Kweskin's reputation was enough to pique Cohn's interest and win some highly prized office time. He had formed a new band, and the band was looking for a label. They would call themselves the Lyman Family, and while Kweskin's name would be featured prominently, it was clear to Cohn that the head of the "family," Mel Lyman, would be pulling the strings. It was Lyman who did most of the talking during the series of meetings in Cohn's office. Unfortunately, as far as Larry Cohn could tell, Lyman was insane.

Peter had gotten to know Lyman as a Boston musician. He admired his playing and counted him as an influence. Truth be told, while Peter Ivers may have been considered the greatest living blues harp player by a few small, knowing circles in Chicago and Boston, the title could well have gone to Mel Lyman. He was certainly its most recognizable public face, having achieved iconic status at the historic 1965 Newport Folk Festival—the year Bob Dylan plugged in and infuriated a generation of folk purists. Lyman had quelled the riotous mob into reverent silence with an impromptu twenty-minute harp solo of the classic spiritual "Rock of Ages." In the brochure for the festival the following year, he appeared in an ad for a new brand of harmonica customized for the blues.

By the time he arrived at Larry Cohn's office, Lyman had at various times claimed to be the living embodiment of Truth, the greatest man in the world, Jesus Christ, and an alien entity sent to Earth in human form by extraterrestrials with a mission to save the world. Nonetheless, it took a series of conversations in his office for Cohn to let Kweskin and Lyman know they were going to have to look elsewhere to be signed. But by that time, Cohn had begun to strike up a relationship with Peter, whom he'd initially written off as a hanger-on. Peter was always ready with a goofy grin and a witty line, and Cohn had to laugh at the kid's chutzpah. Sometimes Cohn would take an almost protective, paternal interest in Peter—warning him, for example, to steer clear of the likes of Mel Lyman, who regularly picked up his phone to hear one of his disciples say, "Hello, God?" and, without a trace of irony, would answer, "Speaking." (71-2)

These were Peter's first words to Lucy Fisher: "I'm the little boy that sits on his knees and gets the special dessert." (74)

The Signet's kitchen was run by a mean Irish cook named Sadie, who took shit from no one, Harvard men especially. She provided one lunch every day, on a large tray that the server would carry around to each table. Only Peter got special treatment. He often sat with his legs tucked under him, and from hard-ass Sadie received customized meals catered to meet what seemed to Lucy like an extended array of food fetishes At the beginning of each lunch, Sadie would direct Lucy to a special tray with the instruction, "Now this is for Peter." When he described himself as "the little boy who sits on his knees and gets the special dessert," he meant it literally. (75-6)

Marriage, though, seemed to Lucy like a very grown-up step. The wedding was planned, the date was set—and Doug had nothing good to say about any of it. Finally, Lucy was unable to contain herself. She popped the question: Why was he getting married at all?

Without hesitating Doug answered, "I have no idea."

Doug Kenney got married in a suit that looked every bit of the twenty-five dollars he paid for it at a store in inner-city Boston. He asked Peter to be his best man. Before the ceremony, Doug seemed skittish, less certain than ever why he was taking this major step. Before the procession began, Peter took him aside and told him that under no circumstances should he feel he was obligated to go through with it. In fact, he wouldn't even have to explain. He could just leave, and Peter would go out and tell everyone the wedding was off.

By this point, though, stopping the wedding probably seemed to Doug like a far more momentous decision than going through with it. One hundred and fifty guests were waiting around the other side of the house. That kind of decision would have taken a Kind of clarity he was never quite able to muster.

With Peter by his side in a loud blue suit, Doug Kenney said, "I do.'" (78)

LUCY FISHER: "When I emerged from the total shock, I found myself repeatedly at the LA Homicide Department—the last place I ever expected to ever be. But every time I climbed the stone steps to that building, I almost exploded with impotence and rage. The detectives seemed more concerned with covering up all the mistakes than in following up the potential leads constantly being thrown their way." (91)

"Hi, I'm Doug Kenney. Can I stay with you guys? I'm a friend of Peter's, he said you wouldn't mind." (96)

[Linda Perry] approached Durrie [Parks], her confidante and partner-in-crime, and asked her point-blank: "Peter is wonderful, but do you really think he should have a record deal?" Without hesitating, Durrie answered "Yes." "Why?" "Because he wants it." Which suddenly, to Perry, made perfect sense. (104)

Some speculated that Peter had gone out in diapers at the Fleetwood Mac show naively expecting to win over the crowd by just being himself. Maybe the unequivocal acceptance he'd enjoyed from Merle growing up, and from a steady stream of friends and admirers in the meantime—whose constant refrain about Peter was that he didn't do things that were cool: what he did became cool—had led him to believe it was only a matter of time: all he had to do was keep doing his thing. Everyone, eventually, would come around. (113)

VAN DYKE PARKS: "To be dropped by a label confers a special kind of character on a person. It brings a certain humility to a person that has been to the mountain, in terms of ego. You are an artist and then all of a sudden you are nothing. That puts a man in the kitchen with the ashes, groveling, who once was great." (118)

Despite tensions in the studio, Peter maintained high hopes for the album. He had a great band, a famous producer, and Carly Simon singing with him on one track. (When an interviewer noted that this put him in the same boat as Mick Jagger, Peter shot back, "We get different mileage out of her, though—in my case I admit I'm so vain.") (127)

Jerry Casale's impression of Peter as a kindred spirit was instantly confirmed. He saw him as an electric bundle of manic mental energy: a kind of new wave shaman, a trickster; an imp. Back in Akron, Mothersbaugh had used a baby mask to create the alter ego he called Booji Boy (pronounced "Boogie Boy"), and Casale became a character they called the Chinaman. They would go out to restaurants and stores in character, playing it straight for shock value and real-life situation comedy. This was art for art's sake; it had nothing to do with a career. No cameras rolled as they sat in middle American diners and deadpanned to the waitress that Booji Boy needed all his food chopped up in a blender because he had a hole where his mouth should have been. Like Devo, Peter was always testing people, always playing, performing his one-man guerrilla theatre for whomever happened to be there. Had they met in Akron, Peter undoubtedly would have been part of Devo. Lucky for Peter, Casale thought, he wasn't in Akron. (139-40)

DAVID LYNCH: "It might have been 1974. I was using Fats Waller in my film Eraserhead, and I had written lyrics for a song called 'In Heaven,' and I needed the music for that, and I needed a girl to sing that. So I ended up at Peter Ivers's house with my friend Alan Splet, and lo and behold, he saw a [Fats Waller] album, and he thought the album was out of print and completely rare, but Peter had all the Fats Waller stuff, and we were very impressed with that. I had all these tapes Alan had saved, but now here was the album, Peter had the album. He had loved Fats Waller from a long time ago, and I knew I had gone to the right guy. So I gave Peter the lyrics, and I apologized for how simple the lyrics were, and he said, 'No no,' and he went to work. And when I went there the next time, he sang the song to me, right in front of me, and he had done the organ in the spirit of Fats Waller. He sat on the couch and sang the thing in a falsetto voice, and it was a done deal. He gave it to me and I walked out." (146-7)

Peter was constantly surrounded by the wives of Hollywood. Rumors ran rampant, but for some reason, since it was Peter, no one seemed to mind. (157)

Lucy's friend Elisabeth Glaser was another Laurel Canyon regular. When she and her husband Paul were in the market for a new place, they stayed with Peter and Lucy. Peter and Paul, an actor who had done some guest spots on shows like The Waltons and Kojak, became fast friends. One night several months after the Glasers had found their own place, Lucy felt they hadn't seen each other in too long and called to invite them out to a movie. Elisabeth seemed shocked by the suggestion, though Lucy couldn't fathom why. Somewhat exasperated, Elisabeth explained that if Paul showed his face in public they would all be mobbed. Lucy still didn't understand. It emerged that since they last spoke, Paul had landed the lead on a new cop show called Starsky & Hutch. The show was a runaway hit, and Paul Michael Glaser was now the most famous lawman-heartthrob in the country. Peter and Lucy, who didn't have a TV, had no idea. They did go out with the reluctant Glasers that night, and sure enough, they were mobbed. (157)

Perhaps even more than the rest of them, this was something Kenney desperately needed—to feel a part of something countercultural, uncorrupted by commerce. Though he had managed to find a voice and a medium that spoke to the masses, sold like crazy, and made him rich, Doug was, at his core, an artist. He felt Caddyshack had been stolen from him, and thus didn't give a damn how well it was doing at the box office. Needling producers had insinuated their influence into nearly every aspect of production: hijacked the editing, added new scenes (many starring a mechanical gopher he had not written and stridently opposed), marred his vision, and stolen his film. (178)

Lucy despised New Wave Theatre. The music was so unmusical, the scene so unpleasant. While still and always Peter's biggest fan—she remained mesmerized every time he picked up the harmonica and never stopped being in the emotional grip of his music and songs—she hated that he was subverting his own work to be, as she saw it, a mouthpiece for David Jove. She understood the value of Peter's using the show to hone his live-camera performance skills, but she also felt that the overweening creepiness of Jove and his milieu outweighed any potential benefit. It was not only beneath Peter's dignity and talent; it felt dangerous in ways Lucy could not fully explain. (182)

Of course, [Doug Kinney's] gripe was really with Lucy. Before starting at Zoetrope, she had signed Doug's production company to 20th Century Fox. Their friendship had been his reason for striking the deal. She was going to help him build a Hollywood-proof studio that would encourage creativity and grant him total control. Not only had she left Doug, but he felt she had left to do the exact same thing for someone else. Coppola, after all, was living Doug's dream even more than Peter's. By virtue of sheer artistic vision, persistence, and will, he had triumphed over the asshole execs, emerging with his artistic dignity intact from the same Hollywood that, in the space of a single film, had taken a chunk out of Doug's soul. There were no mechanical gophers in The Godfather or Apocalypse Now. Lucy was supposed to protect Doug and help him get his integrity and career back on track. Instead he felt Big Sis had abandoned him for a more glamorous family headed by the all-time coolest Dad. (184-5)

As Tim concluded, Peter took his suit jacket off and wrapped it around his waist like a little boy. The ropes suspending Doug's coffin began lowering it into the ground.

A sudden sound filled the air, and a few people looked up, startled—was that a note, a chord? It was music. Peter stood over the scar of turned-up earth as his best friend was lowered into it and eulogized him in the language he knew best. He sent Doug Kenny into heaven with an angry blues version of a song called "Beautiful Dreamer." Without saying a word, he expressed what everyone on the hilltop by the duck pond was feeling. They stood silent; listening and crying.

Peter blew a last snarling chord, hurled his harp into the grave, and fell to his knees and screamed. (188)

ROD TAYLOR, friend, collaborator: "The truth is, there is a path to success for an executive. There is no path for an artist. An artist is out there with a prayer and a smile, and then they stop smiling back." (192)

MICHAEL O'KEEFE: "There was this sort of urban myth spreading back then that music was going to be a revolution in America, we all thought that being in the movie industry, we were going to change everything and that the world was going to change. There was this sort of wave people rode in the '60s and '70s people were still surfing on. Nothing could have been further from the truth. What was coming was the '80s." (197-8)

MICHAEL O'KEEFE: "I remember seeing this documentary footage of Abbie Hoffman in the '60s, probably in Chicago, a low-grade video and he was saying something insane to the camera like, send us the drugs, send us the guns, and we'll take care of the revolution. That's kind of what everyone was thinking somehow. That just because we were feeling rebellious there was going to be a revolution. And there wasn't." (198)

The punks did not know about Peter's albums, they did not know he had played with many of their musical heroes or that those musicians held him in the highest regard. Had they known about his relationship with Little Walter and Muddy Waters; or that he often sat in on harmonica with John Cale of the Velvet Underground; or that Devo had played his song at every show of their '79 tour—perhaps they may have treated him differently. In fact, most of the New Wave Theatre bands did not even know he was a musician. They just thought of him as a faggy poser with a TV show they would happily use if it could help them get seen. (215)

Belushi had been introduced to Fear's music by Peter during the first year of New Wave Theatre. While Peter had been the conduit for many of the "punk comics" to access the underground scene, Belushi had delved in the deepest, turning his legendary appetite to the insatiable consumption of punk rock. Peter and Belushi had initially connected over their love of blues, and both saw the direct line pointing from blues to punk in a way their colleagues—both their musician friends, most of whom had disdain for punk, and their comic friends, who appreciated the attitude and the scene but would never listen to the music on its own merits—did not. (226-7)

HUDSON MARQUEZ: "Anyone interested in the blues immediately gets punk rock. So John just flew off the deep end for punk because it was another chance to get wild. And you don't have to do any twist dance steps, you can jump up and down." (244)

Merle, Lucy thought, put it best. She would say that Paul was the kind of person that, if Peter were elected president of the United States, his father would have said, "Yeah, but look at the shmuck he beat." (233)

STUART SHAPIRO: producer and creator of Night Flight: "I was very involved in midnight movies. Pretty much horror films and music films. It was the very beginning of cable and [cable] really signed off by, like, eleven o'clock at night. It's like nobody lives after eleven or twelve o'clock. I was sitting there in New York watching this, and all over the country thousands and thousands of people are going to midnight movies. I just had the desire to put that kind of cultural philosophy into programming on cable. Discovery was the most important ingredient about Night Flight. You could come and sit down and know that you would be turned on to discover something, no matter what segment it may be." (235)

DAVID CHARBONNEAU private detective : "He [David Jove] said, 'Let's go out,' so we got a bite to eat. Then we went back to his place, and he cued up, slow motion, Reagan getting shot And he stopped it right at the point when Reagan was getting shot, and he just played it over and over and over. By the third time, I asked him, 'What are you doing?' And he goes, 'I just love this part.' And I go, 'Great.' He says, 'Can't you just see the realization on his face?'" (248)

PENELOPE SPHEERIS, punk documentarian, producer: "To be honest with you, and you're sure the guy is dead, right? Because he scared the shit out of me. Oh, punk rock didn't scare me at all. The reason he scared me is, people that scare me are people who don't know who they are. He was so psychologically unstable and scrambled up that just looking in his eyes gave me cold shivers. He scared the shit out of me and I'd go to great lengths to stay away from him. I'm not easily scared, okay. I'm pretty tough and brave. " (248)

PLEASANT GEHMAN, writer: "I can see exactly why some people wouldn't talk to you unless he was dead." (249)

A few days ago Peter had spoken on the phone with Tim Mayer, whose long-awaited Broadway debut had not gone as planned. The much-heralded Gershwin musical was scheduled to open in two months, directed and choreographed by Tommy Tune and starring Twiggy. Mayer wrote the book and would be credited as such, but throughout rehearsals, his erratic unpleasant behavior had made enemies of nearly everyone involved with the production, a number of whom he genuinely admired. Mike Nichols was brought in to help smooth things over, but Mayer managed to alienate him, too. Finally, Nichols told Mayer something that many others of lesser stature had undoubtedly wanted to tell him many times before. "Tim, we know you're the smartest person in the room. Now shut up." Mayer was banished from the set. (272)

HAROLD RAMIS: "What is tantalizing, and I don't usually think in terms of what if, but if Doug, Peter, and Belushi had survived, what would they be doing, you know?" (275)

HAROLD RAMIS: "Imagine, surrounded by your friends, everyone close to you, and knowing that one of them could have killed him. I mean, how do you live with that?" (279)

DAVID CHARBONNEAU: "I'm driving three hours to get home and go to bed so I can meet Petrovsky [the lead detective] back at eight o'clock in the morning. I got home, stashed the diary, slept for three hours, woke up, and went to Petrovsky. And he asks, 'What've you got?' And I said, 'I've got a lot, I got this [diary] last night.' So I said, 'Alright, if you want my theory, here it is. My theory is David Jove psychologically, David Jove with opportunity, David Jove for financial reasons, David Jove because Peter was his alter ego and leaving him, and throw in this Jove [Ecstasy] deal. Peter Ivers was scared.'

"I was dumped off the case at about two in the afternoon. Same day." (281-2)

DAVID CHARBONNEAU: "David would call every five years out of the blue. The last time I talked to him, David was still throwing all the theories out there and saying, 'It's too bad no one will ever know, and don't you feel they pulled one over on you.' Just fucking with me. I just said, 'You know, David, there's no statute of limitation on murder,' and that's the last thing I said to him, there was no response. It was a game, always a game. Not long before he died he called me." (284)

ANNE RAMIS: "[Jove] would answer the phone with, 'Did you kill Peter Ivers?' " (284)

Back in his car, Rafelson remembered that Peter had scribbled something on the inside cover of the novel. He opened it and read the inscription.

"Every decision you make is a chance to be a hero." (289)

|