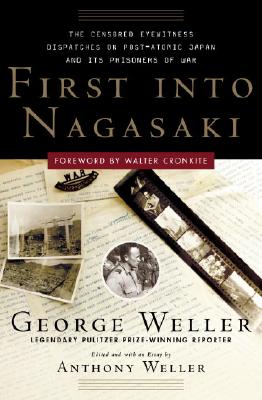

First Into Nagasaki: The Censored Eyewitness Dispatches on Post-Atomic Japan and Its Prisoners of War

George Weller (2006)

George Weller's dispatches from Nagasaki, just four weeks after the bombing, were censored and destroyed by General MacArthur. Weller salvaged his carbon copy but, in his subsequent travels to many corners of our troubled globe, the copy disappeared. His son, an honored writer in his own right, has only recently uncovered it and this book is the result. (ix)

This total blackout, of course, depended on keeping reporters and photographers from the scene. George Weller was both reporter and photographer, and his daring and secret entry into Nagasaki just four weeks after the atomic attack threatened to destroy that hope. He wrote and photographed the still-smoldering and dying city and its dead and dying population. His reports, so long delayed but now salvaged by his son, at last have saved our history from the military censorship that would have preferred to have time to sanitize the ghastly details with a concocted, fictional version of the mass destruction and killing that man's (read that "America's") newest weapon had bestowed on civilization. (x)

In the prior world war, the majority of the losses had been combatants—meaning civilians turned soldier. World War II made mass civilian deaths central to the equation of modern war, to force an enemy to capitulate. When it was over, civilian deaths (55 million) were more than double those of combatants (22 million).

Beginning near the end of 1944, the United States waged a punishing air assault against Japan. Its industrial areas were all heavily populated cities that were largely made of wood, ideal for incendiary bombs. For example, in a three-hour air raid on Tokyo in March 1945, sixteen square miles of the city were destroyed, a million people made homeless, a hundred thousand torched to death—and nearly a fifth of the city's industrial capacity obliterated. This was known as area bombing, and years of Japanese atrocities against civilians and soldiers all over the Pacific and across Asia were thought ample justification. Since Japan knew only the concept of "total war," now it was receiving the same in return. (Introduction)

Whenever I see the word "Nagasaki," a vision arises of the city when I entered it on September 6, 1945, as the first free westerner to do so after the end of the war. No other correspondent had yet evaded the authorities to reach either Hiroshima or Nagasaki. The effects of the atomic bombs were unknown except for the massive fact that they had terminated the war with two blows in three days. The world wanted to know what the bombs' work looked like from below.

I had just escaped the surveillance of General MacArthur's censors, his public relations officers and his military police. MacArthur had placed all southern Japan off limits to the press. Slipping into forbidden Nagasaki, I felt like another Perry, entering a land where my presence itself was forbidden, a land that now had two Mikados, both omnipotent. (3)

After submitting to the censors of the MacArthur command ever since I had escaped from Java in March, 1942, I felt I could not take much more. I remembered how his censors, perhaps eager not to offend or alarm the White House, killed a dispatch I wrote criticizing Roosevelt's defeat by Stalin at Yalta. With security no longer in question, I was not going to be stifled again. But I was not unaware that in planning to slip into an atomic city first, I was also risking repudiation by the conformists in my own profession. Four years earlier they had ceased bucking the communique-fed hamburger grinder, and they disliked—while perhaps secretly admiring—anybody who kept on trying to report the war, to make the public think as well as feel. (5)

And then I felt rising in me, like a warm geyser, a jet of confidence. It is like the moment when a poem unties your mind. (7)

Already I had a formula that held off the most officious questioners. I looked them in the eye and said very softly, "Please consider your position." When they did, they blanched and departed. (10)

I saw that the first Japanese official who guessed our real identity would get the police to put us in custody "for your own protection," exactly as MacArthur was doing with my colleagues, and telephone to Tokyo for the MPs to come and pick us up. Lacking even a revolver, we could not defend our mission with force. There was only one protection we could assume: rank.

Rank! In war it will get you everything but mail.

I therefore awarded all members of my command spot promotions, starting naturally with myself. I became Colonel Weller. In hardly an hour, between Yamaguchi and Nagasaki, Harrison rose from sergeant to major. He could not have done better in Cuba. The three Dutch privates became lieutenants in an inter-Allied working party so dense with secrecy that they communicated with me part of the time in German, the enemy language. (11)

I did not look at the general, but I spitted the lieutenant with a glance. "If the general doubts our authority," I said icily, "I suggest that he telephone directly to General MacArthur for confirmation." The general, who understood more English than he let on, glanced at the lieutenant, inviting comment. The lieutenant scrutinized me a shade more respectfully. "But in making such a call," I said, "the general should consider his position." Now I looked at the general. There was a nervous pause. The general said something low and rapid.

"General says you are very welcome in Nagasaki, Colonel. He will give orders to show you everything." I nodded casually, as if no other result was ever thought of. (13)

From September 6 until September 10 Weller stayed in Nagasaki, exploring the blasted city each day, writing his dispatches far into each night, then sending them off to MacArthur's military censors in Tokyo, hopeful that they were being cabled onward to his editors at the Chicago Daily News and thence to a vast American readership via syndication. These dispatches have remained unpublished for sixty years; it appears that the U.S. government destroyed the originals. Weller's own carbon copies were found in 2003. (24)

Controlled and quiet in his account, Farley said, "I was looking up the harbor toward the Mitsubishi plants five miles from here when I saw a terrific flash. It was white and glaring, very like a photographer's flare. The center was hung about 1,500 feet from the ground. Light was projected upward as well as downward, something like the aurora borealis. The light quivered and was prolonged for about thirty seconds. I instantly caught the idea that it was something peculiar and hit the ground. The building began to shake and quiver. Glass shattered around me; about one-third of the windows in the camp broke. After the blast passed, I saw a tall white cumulus cloud, something like a pillar, about four or five thousand feet high. Inside, it was brown and churning around." (35)

Those human beings whom it has happened to spare sit on mats or tiny family board-platforms in Nagasaki's two largest undestroyed hospitals. Their shoulders, arms and faces are wrapped in bandages. Showing them to you, as the first American outsider to reach Nagasaki since the surrender, your propaganda-conscious official guide looks meaningfully in your face and wants to know: "What do you think?"

What this question means is: Do you intend writing that America did something inhuman in loosing this weapon against Japan? That is what we want you to write. (37)

The atomic bomb's peculiar "disease," uncured because it is untreated and untreated because it is undiagnosed, is still snatching away lives here. Men, women and children with no outward marks of injury are dying daily in hospitals, some after having walked around for three or four weeks thinking they have escaped. The doctors here have every modern medicament, but candidly confessed in talking to the writer—the first Allied observer to reach Nagasaki since the surrender—that the answer to the malady is beyond them. Their patients, though their skins are whole, are simply passing away under their eyes. (43)

The Japanese POW camps are one of the great omissions in World War II memory. Despite the large numbers involved—140,000 Allied prisoners through the war—they have not been portrayed in films, chronicled by historians, or officially documented as the Nazi camps have been, though they were seven times deadlier for a POW. The Pacific war was as much a tribal struggle of race, with all its mutual incomprehensions, as a struggle of nations. (48)

Corporal Jesus Silva (Santa Fe): "It was so bad underground that your friend would ask you to go off into a dark lateral passage with him, hand you a crowbar and reach out his foot or arm, and whisper, 'Will you, please?' You knew that meant for you break it, which would mean thirty or forty days' rest for him. For asking the Japanese foremen to remove the timbers preventing my crew from building a wall face, I was severely beaten by three overseers who took turns smashing their fists into my face. They wanted me to go to my knees and ask for mercy but I refused. Finally one took a club and knocked me out." (53)

For hundreds of Americans held in Kyushu prison camps, the atomic bomb bursting over Nagasaki in full view was a signal of their liberation from serfdom in Baron Mitsui's cruel and dangerous coal mine. Some Bataan and Corregidor prisoners were worked to death here. (58)

Corporal Lee Dale (Walnut Creek, California), who visited the Nagasaki atomic bombsite: "Those flattened buildings made you want to cry, not on account of the lives lost, but because of the destruction involved." (61)

Driver Bain Norwich: "The parents of all the Japanese I have met could never have been married." (74)

Sergeant Noel Robins (Centennial Park): "A huge multicolored cloud rose upwards, giving the impression of an extraordinary bombing. I cannot visualize a punishment harsh enough for the vultures of the east." (78)

Sergeant Edward Head (Adelaide): "Japanese civilians must be happier now that the army yoke has been lifted from their shoulders." (82)

Driver Pat Lynch (Warracknabeal): "Not enough Japanese were killed." (82)

Dick Lavender (Lewiston, Idaho); "I gambled by hitting back the first Jap who hit me, and had peace that way for the first nine of my twenty-six months underground. Later a new boss called Smiley began beating me daily. I stood him for two weeks, then threatened to beat him back, and he stopped just like the first one." (96)

In Java, the prison enclosure at Bandoeng had two sets of captives: 5,000 men, Allied military, and 1,200 ducks, Javanese. By a system of ruses the Allied prisoners, who were always hungry, found a way of stealing the eggs laid in captivity by their fellow prisoners. Egg production went down 50%. The commandant blamed the ducks. He studied their lives and reached the conclusion that they were dissolute and frivolous. One day he ordered all the ducks to be driven off their ponds and arranged before him in as orderly a fashion as frightened ducks could be. Then, roaring at the top of his voice, he delivered them a lecture.

"Your egg production is down, do you understand?" he shouted. "And why has it fallen? It is not for lack of food. Do not tell me you are starving. You eat well. But you are not like Japanese ducks. You are lazy. You simply do not wish to lay. You are insubordinate ducks, obstructionist ducks. Well, I have a cure for that. For two days you will go on half rations." The commandant dismissed the ducks without seeing the abashed looks on the faces of the Allied prisoners who had overheard his lecture. (106)

Inevitably, this book is as much about being a war correspondent in 1945 as it is about what one man saw. The ease of modern communications can make us overlook the fact that, until recently, a reporter's challenge lay in surmounting the problems not only of "getting in," but of swiftly being able to get a story out. There were no instantaneous satellite links, only cable offices within reach if one were lucky, where—along with normal, excruciating delays—the tendrils of military and government censorship could be too muscular to remove.

Their equivalent nowadays is still effective: to stop a story at its source by limiting access. If you can control what is witnessed, you can mold what is reported. Since news organizations are rarely anxious to announce their shortcomings, a credulous public remains, as usual, none the wiser. (244)

I also believe that the dispatches hold a particular relevance not just from their content, but from the official will to silence them Jack in 1945. In our era of the controlled, hygienic "embedding" of journalists in war zones, amid current disputes over a government's right to keep secrets, the Weller dispatches represent a kind of rogue reporting that many militaries may have snuffed out, but which is still essential to learning the truth. (245)

Sneaking into a nuclear site for an entire series of articles a week later, however, defying both a travel ban and a media blackout, was not going to get past those same censors. (It's unclear if MacArthur ever learned that Weller also impersonated an officer.) By some accounts, the general—trying to ensure his glory as Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers while hiding the bomb's lethal radiation and the fact that no medical aid, not even an observer, had been sent to the dying even weeks after the surrender—was absolutely livid at Weller's effrontery. And because the reporter was still under MacArthur's control in Occupied Japan, had he succeeded in getting the censored dispatches out, his newspaper could never have published them without losing its invaluable accreditation there, which was unthinkable. (247)

He received a 1943 Pulitzer Prize in foreign reporting for the story of an emergency appendectomy performed by a pharmacist's mate while on a submarine in enemy waters.

En route back home in late 1943 for leave he wrote Bases Overseas, a controversial book proposing a global system of U.S. bases. ("The largest army, the largest navy, and the largest industrial plant in the world: such are the unthinking aims of strategically incurious minds ... In a country dominated by this cult of production, the where of its conflicts are nothing.") (251)

Facilities included plush transport on two B-17 Flying Fortresses equipped with desks, lamps, long-range transmitters, and best of all, a CENSORED stamp that hung over McCrary's desk. "Help yourself, guys," he told them cheerfully. "You're the censors on this show."

The intention, naturally, was to make sure the bomb got portrayed as the U.S. government wished. (255)

Perhaps. Tex did get his charges into Hiroshima, which was part of the unstated goal of the mission: to report appropriately the bomb's ability to demolish a city with one strike. Whether or not the junket members realized, a corollary purpose was to make it evident there was no dangerous radiation involved. That might be arguably too much like the use of, say, poison gas. (256)

|