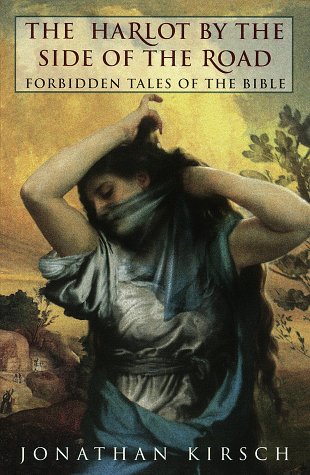

The Harlot by the Side of the Road: Forbidden Tales of the Bible

Jonathan Kirsch (1997)

I first discovered what is hidden away in the odd cracks and corners of the Holy Scriptures when, many years ago, I resolved to acquaint my young son with the Bible as a work of literature by reading aloud to him at bedtime from Genesis. (2)

When Ham, father of Canaan, saw his father naked, he told his two brothers outside. So Shem and Japheth took a cloak, put it on their shoulders and walked backwards, and so covered their father's naked body; their faces were turned the other way, so that they did not see their father naked. (Gen. 9.:20-24 NEB)

After that scene, so comical and yet so disquieting to any parent mindful of Freud, I read the Bible more slowly, rephrasing certain passages as I went along and omitting others altogether. My son, already media wise at five, soon began to protest. If I paused too long over a troublesome passage, trying to figure out how to tone down or cut the earthier parts, he would sit up in bed and demand indignantly: "What are you leaving out?"

In a sense, his question prompted the book you are now reading. . As I read the Bible aloud to my son, I found myself doing exactly what overweening and fearful clerics and translators have done for centuries—I censored the text to spare my audience the juicy parts. And so my son's question is answered here: The stories collected in these pages are the ones that I—like so many other shocked Bible readers over the millennia—was tempted to leave out. (3-4)

One rewritten version of a biblical narrative actually found its way into the Bible itself. The first and Second Books of Chronicles, the very last books of the Hebrew Bible, are essentially a sanitized version of the court history of King David that appears in its unexpurgated form in the First and Second Books of Samuel. The author of Samuel is admirably honest about David, sparing no detail of the various sexual excesses and crimes of passion that tainted his reign, but the author of the Chronicles insists on cleaning up David's reputation by simply cutting the more lascivious stories. The Book of Samuel, for example, devotes considerable attention to the deadly love triangle between David, Bathsheba, and her husband (2 Sam. 11). To judge from the Book of Chronicles, however, none of it ever happened. "See what Chronicles has made out of David!" exclaimed Julius Wellhausen, an early and important German biblical scholar who allows us to understand that the real authors of the Bible were ordinary human beings who were perfectly willing to engage in a cover-up. (6)

One of the meanings of t'sahak is "laugh"—a play on Isaac's name—and that's the one on which the translators, old and new, have relied in suggesting that Ishmael merely "mocked" or "laughed at" Isaac. What the translators are reluctant to let us know is that another meaning of t'sahak is "fondle," and the original Hebrew text of the Bible may suggest that what Sarah actually saw was some kind of sex play between Ishmael and his little brother.

Indeed, the very same Hebrew word that is used to describe what Ishmael does to Isaac appears only a few lines later in Genesis to describe Isaac fondling Rebekah outside the window of Abimelech, King of the Philistines. (49-50)

The murder of the prince and his lover is enough to halt the plague that is ravaging the camp of the Israelites as a divine punishment for their "harlotry," but the carnage is not over yet. Not content with the extermination of a single temptress, and apparently overlooking the fact that his own wife and in-laws are Midianites, Moses sends Phinehas and his comrades-in-arms on a mission to kill as many of them as possible. All of the Midianite men are slain, and all of the women and children are taken captive—but the decision to spare the women and "their little ones" turns out to be an act of dubious mercy. Moses is surprised and annoyed at his captains for bringing back so many prisoners of war along with the customary plunder and booty, and he coldly utters a command that we are shocked to hear on the lips of the man who brought down the Ten Commandments from Mount Sinai.

"Have ye saved all the women alive?" Moses complains, plainly irritated at the sight of so many potential seducers of Israelite men, so many Midianite mouths to feed. "Now therefore kill every male among the little ones," he continues, "and kill every woman that hath known man by lying with him." Only the virgin girls are allowed to survive, Moses decrees, and they are consigned to his men of war for their own pleasure (Num. 31:15-18).

The slaughter of the Midianites comes as an appalling surprise to most casual Bible readers precisely because the clergy of both Judaism and Christianity have preferred to focus on the kinder and gentler passages of the Holy Scriptures. But the plain fact is that the Bible accommodates both love and hate, mercy and vengeance, life and death, and often in the very same passages. (91)

The rape of Dinah in the Book of Genesis and the seduction of the Israelite prince in the Book of Numbers are offered as morality tales, not atrocity stories, and they are meant to caution the readers of the Bible against the temptation of strange gods and goddesses and, above all, the men and women who worship them. For the redactors who slipped these two tales into the Bible and put their own spin on them, the real atrocity in each story is not the mass murder of men, women, and children, but the single act of seduction by a stranger that precedes it. (92)

God's solution is to declare a war of conquest—we might easily use the terms "ethnic cleansing" and even "genocide"—against the native dwellers of the Promised Land. The slaughter of Midianites that we encountered in the Book of Numbers is only an augury of the bloodthirsty campaign in Canaan itself. According to the rules of war set forth in Deuteronomy, the invading Israelites are obliged to "proclaim peace" to a besieged city, and if the city-dwellers respond with "an answer of peace" then their lives are to be spared and they are to be permitted to live as "tributaries" to the Israelites. But these rules of engagement apply only to the "far off' cities. An entirely different strategy is decreed for the cities within the Promised Land itself, the cities of the Canaanites and the other peoples who dwelled in Canaan before the Exodus.

[Of] the cities of these peoples, that the Lord thy God giveth thee for an inheritance, thou shalt save alive nothing that breatheth, but thou shalt utterly destroy them. (Deut 20:10-18) (126-7)

According to Egyptian lore, Isis is the wife and sister of the divine ruler Osiris, who is treacherously slain by his jealous brother, Seth. In one version of the Isis myth, Seth tricks Osiris into lying down inside a wooden chest, then seals the chest and casts it into the Nile—an image that evokes the baby Moses afloat in his little boat of reeds. The heartbroken Isis searches tirelessly for the chest containing the remains of her dead brother-husband-lover, but when she finds it at last, Seth manages to dismember the body and scatter the pieces: Isis tracks down the remains of Osiris and finds all but one crucial body part—his penis.

Now Isis engages in a magic ritual that is as thoroughly and weirdly erotic as the one Zipporah uses to stave off the night attack by the Almighty. Isis reassembles the pieces of her dead lover, using a wooden likeness of a male sexual organ in place of the missing one, and breathes life back into Osiris by waving her wings over the reassembled corpse. Then she engages in sexual intercourse with Osiris and succeeds in impregnating herself with a son who will be called Horus. By the traditions of ancient Egypt, the reigning pharaoh was seen as an incarnation of Horus, his immediate predecessor on the throne as Osiris, and both his mother and his wife were seen as Isis. "His sister was his guard," goes an ancient ode to Isis and Osiris, and the ode continues with words that could be used to describe Zipporah and the night attack at the lodging place:

She who drives off the foes,

Who stops the deeds of the disturber

By the power of her mighty utterance.

The decisive clue to the linkages. between Isis and Zipporah, according to feminist Bible critic Ilana Pardes, is the fact that Isis is a winged goddess who is often depicted in Egyptian hieroglyphics as a hawk or a kite hovering over the sexual organ of the dead body of Osiris. "We have here a violent persecutor, a wife saving her husband, a penis undergoing treatment ... and above all, wings!" argues Pardes. "Zipporah means 'bird' in Hebrew, and I venture to suggest that this name discloses her affiliation with Isis'' (166-7)

Only the most daring of Bible critics argue that the figure of Zipporah in the Hebrew Bible was somehow inspired by an Egyptian goddess, but no open-eyed reader will fail to notice that something strange is happening in the cracks and corners of the biblical text. Perhaps the Bridegroom of Blood is, as Pardes insists, an intriguing remnant of "a repressed pagan past" that surfaces in the biblical text despite the best efforts of the priestly censors to conceal it from our eyes. (168)

The text prompts so many provocative but unanswered questions that we begin to wonder if we really know who the deity called Yahweh is, what he is capable of doing, or what he wants from us. (168)

Certainly the Israelites saw some relationship between the god (el) called Yahweh and the supreme god whom the Canaanites called El—and perhaps, at some early moment in their history, the Israelites saw the two gods as one and the same. Abraham, for example, encounters a Canaanite king and high priest who blesses him in the name of El Elyon—"God Most High, Maker of heaven and earth"—and Abraham seems to identify and embrace the deity as his own (Gen. 14:19). Later, when God discloses to Moses that his personal name is actually Yahweh, the Almighty explains: "I appeared unto Abraham, unto Isaac and unto Jacob, as El Shaddai"—a phrase that is conventionally translated as "God Almighty" but one that also harkens back to the all-mighty god of Canaan (Exod. 6:3). (221)

Some passages of the Bible are simply so weird, so fundamentally at odds with the cosmology of the rest of Holy Writ, that they present themselves as wild atavisms of some far older and long-suppressed faith that existed in ancient Israel before the biblical authors created the Bible. The night attack on Moses in Exodus is one example, and the sudden appearance of the "sons of God" in Genesis is another: "And it came to pass ... that the sons of God saw the daughters of men that they were fair, and. they took them wives, whomsoever they chose. . . . . and they bore children to them, the same were the mighty men that were of old, the men of renown" (Gen. 6:1-3, 4). Bible scholars of several faiths have struggled to explain away the unsettling fact that the Bible conjures up a randy gang of demigods who are fathered by the Almighty himself and go on to sire a race of giants on earth, the so-called Nephilim. (222)

In fact, some of the biblical authors themselves were clearly uncomfortable with the candor displayed in Samuel and Kings. So we are given a second version of the lives of David and Solomon in First and Second Chronicles, which appear as a kind of afterthought at the very end of the Hebrew Bible. David's love for Jonathan, his adulterous and murderous affair with Bathsheba, the rape of Tamar, and the insurrection of Absalom are never mentioned by the author of Chronicles, and other incidents in the reign of King David are boldly revised and rewritten to serve the author's theological agenda: the legitimacy and longevity of the Davidic line. For example, it is plainly reported in the Second Book of Samuel that David is ordered by God to conduct a census of the Israelites, something regarded as odious by ancient Israelites because a census was the first step toward taxation and conscription—and then, rather perversely, God turns around and punishes David and the Israelites when the king complies! (2 Sam. 24:1, 15). But the propagandist who composed Chronicles simply erases the name of God and writes in the name of Satan when retelling the very same story: "And Satan stood up against Israel, and moved David to number Israel" (1 Chron. 21:1). (296)

At first blush, of course, what's "hot" about the forbidden stories of the Bible are the shocks and surprises that await the reader who expects to find only Sunday school stuff—the frank and mostly nonjudgmental accounts of seduction, exhibitionism, voyeurism, adultery, incest, rape, and murder. Sometimes it is hard to make out the moral example that the biblical authors intend us to see in these tales of human passion. And that is why the stories we have explored here have been censored, banned, mistranslated, or simply ignored by preachers and teachers who found them too hot to handle.

But these stories are "hot" in quite another sense. As we have seen, the Bible is littered with the artifacts and relics of ancient beliefs and practices that come as a surprise to anyone who has been taught to regard the Bible as a single-minded manifesto of ethical monotheism. The depiction of God as a mischievous and sometimes even murderous deity is shocking to anyone who envisions the Almighty as a heavenly , father and "King of the Universe," benign and compassionate, slow to anger and quick to forgive. By the time we finish reading and pondering these troubling stories, we are left with the unsettling realization that something very odd was going on in ancient Israel before the priests and scribes came along and cleaned up the biblical text—and we have only a faint if provocative notion of what it was. (305-6)

The Bible itself refers to several intriguing works that are now lost to us, including the Book of Yashar, the Book of the Battles of Yahweh, and the Chronicles of the Kings of Judea. We can only speculate on what these books contained and why they were not preserved along with the books of the Bible and various noncanonical writings that survive as the Apocrypha, but it is clear that the biblical authors knew and used these other sources. (324-5)

The Septuagint also gives us some of the familiar divisions of the biblical text into two paired books. The Book of Samuel, for example, can be accommodated on a single scroll when rendered in Hebrew, which contains only consonants and takes up much less space on a sheet of paper or parchment than the same text in a language that includes both vowels and consonants. The Septuagint, by contrast, required two scrolls to accommodate the Greek translation of the Book of Samuel, and so the translators divided the text into what we know today as the First and Second Books of Samuel. The same technique is preserved in other biblical works that are conventionally divided into first and second volumes in modern Bibles. (329)

|