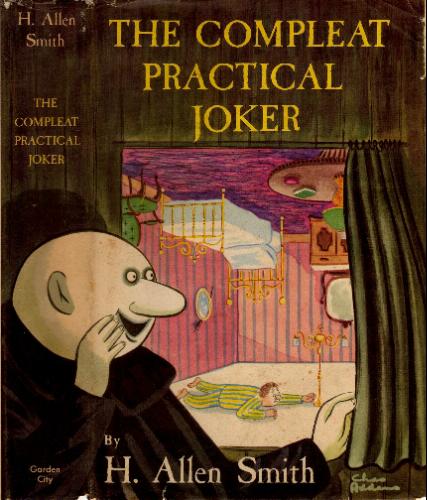

The Compleat Practical Joker

H. Allen Smith - (1953)

Sometimes I think the problem is largely a semantic one. The trouble lies in the designation itself: practical joker. They wince when they hear it and vow they'll have nothing whatever to do with such a depraved person. But call him a prankster and no obloquy attaches to him. It all adds up to the same thing; yet a prankster is a gay and witty fellow, whereas a practical joker is an oaf; Putting it another way, a practical joke is played on you; you play a prank on someone else. (7)

I was told recently of a prominent New York attorney who had occasion to visit a warehouse in Brooklyn. In the warehouse he saw an antique barber chair which was for sale. He bought it. He remembered that once during a world tour he had spent a couple of days in Calcutta and he knew the name of one of the principal business streets there. He had the old barber chair crated and shipped to an address on that street—an address he simply pulled out of the air. And he spent many enjoyable moments thereafter speculating on the bewilderment of the people who received the chair. (18)

Jim Moran, an American philosopher whose exploits have been examined in several of my previous books, was invited one day to a genteel party in the Beverly Hills Hotel. When Jim walked in he was wearing, in addition to his dinner clothes, a piece of string. It was an ordinary piece of grocer's twine. It was looped around his right ear and knotted, and ran down his cheek and into the corner of his mouth.

No one could help noticing it, but Jim made no mention of it as he went from group to group, shaking hands and making small talk. He discovered immediately that no person in the room would speak of it. Nor would anyone pretend to even notice it. Yet he was well aware that his string was a major attraction. People were whispering about it, speculating about it, and getting nowhere. Jim was his most charming self all through the party, occasionally drinking a cocktail without removing the string from his mouth, and at one point, when he undertook to eat a few canapes, he knew that every eye was on him. In the end he departed without a single person having spoken of the string.

Jim tried it at other gatherings, both public and private, with the same result. The string was never mentioned. It was one of those things, mysterious to be sure, but extremely private—a thing one simply doesn't notice.

Now and then Jim had occasion to fly from California to New York and back and usually these trips were taken alone. He began wearing his string on the planes. He'd manage to get an aisle seat so that a maximum number of passengers could not avoid seeing the string running from his ear to his mouth. He'd sit calmly reading a book or a magazine, well aware of the stir he was creating among his fellow passengers. He enjoyed speculating on the various explanations they were attempting. (18-19) [Cp. Alan Abel, who would hang a string out of his mouth to avoid having airplane seat-mates.]

During the nineteenth century foreigners on the order of Dickens and Mrs. Trollope, who came to look at America and write about what they saw, are said to have been hoaxed unmercifully by frontiersmen. Captain Frederick Marryat in A Diary in America (1839) wrote:

"The Americans are often themselves the cause of being misrepresented;. there is no country perhaps in which the habit of deceiving for amusement, or what is termed hoaxing, is so common. Indeed, this and hyperbole constitute the major part of American humour. If they have the slightest suspicion that a foreigner is about to write a book, nothing appears to give them so much pleasure as to try to mislead him: this has constantly been practiced upon me, and for all I know, they may in some instances have been successful." (30) [Cp. Hugh Troy]

Or, let us examine the famous and fashionable St. Thomas's Church on Fifth Avenue. This edifice was designed by Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson. Among the firm's architects assigned to the job was a young man, name unknown to deponent, with a rather perverse sense of humor. He slipped in two decorative details which hadn't been ordered. He worked a dollar sign into the tracery above the Bride's Door of the church, and three moneybags initialed "J.P.M." carved above the choir stalls. (41) [See also]

The men who operate these Fun Houses say that if it were not for the blowhole, their business would likely fail. (42)

Two eastern college boys once spent their summer vacation as temporary employees at Yellowstone Park. After a while they became impatient with a certain ranger, a pompous individual whose job was to guide tourists to the famous geysers and lecture to them on the wonders of this unique manifestation of natural force. They came, in fact, to dislike the man heartily and so they put their heads together and came up with a scheme.

There was one geyser which spouted with clocklike regularity and the college boys stationed themselves near it. The ranger would arrive with his party of tourists. The boys had placed themselves beyond a slope where the tourists could see them while they were out of sight of the lecturing ranger. They had a steering wheel and post from an old automobile, and they had stuck the post into the ground. While the pompous ranger lectured, they'd pretend to busy themselves with hidden valves and gauges and so on. They were able to judge the precise moment when the geyser would let go with all its force—it always signaled its intentions with a couple of preliminary puffs of steam. So, at the exact moment, one boy would yell, "Let 'er go, Charlie!" The other would swing the steering wheel vigorously. And the geyser would shoot a hundred and fifty feet into the air. There may still be tourists who believe the Yellowstone geysers are a colossal fraud, operated by an underground steam system. (77-8)

Many years ago there was a town called Little Rest in Rhode Island. Apparently it was a community made up almost entirely of practical jokers. They were constantly at work, playing tricks either on visitors or on one another. Thus the town got its name—the people who lived there got little rest. Subsequently the community changed its name to Kingston.

In another part of the country a specific practical joke, according to legend, gave a town its name. A whimsical traveler on one of the main trails in the State of Georgia painted, on a large rock, the words, "Turn Me Over." Other travelers heaved and struggled to turn the rock over. On the underside of it they found painted, "Now Turn Me Back That I May Fool Another." They sat down and laughed, or cussed, and then moved on. Eventually, however, a village came into being on the spot, and was called Talking Rock. (82) (See also: Talking Urinal)

When the railroads first came to the West, the locomotive engineers sometimes enjoyed themselves at the expense of the crowds that assembled to watch the arrival and departure of the monsters. A train would pull into a community, with every living creature in fifty miles present to see it. As the gaping crowd gathered around the locomotive the engineer would suddenly let go a blast of steam, then yell: "Watch out, boys, I'm gonna turn 'er around!" That always sent them scattering for the woods. (82)

If the practical joke represents the spirit of the frontier, then the frontier still exists in Nevada. Early in 1953 the government resumed its atomic bomb experiments in the Nevada desert. The most publicized of these test explosions was the one in which two houses were erected near the point of the blast. Dummies of men and women and children were installed in the houses for the purpose of finding out how human beings would fare in an actual bombing. A day or two before the explosion, groups of prominent citizens were escorted into the target area so they might inspect all these arrangements. One of these groups was made up of religious dignitaries. They were about to inspect the interior of one of the target houses when, by good fortune, a military officer went in ahead of them to find out if everything was shipshape. Everything was worse than that. The officer came out and ordered the inspection held up for a few minutes. He gave no explanation to the clergy but soon took them inside and showed them around.

Someone, just prior to the arrival of the religious group, had rearranged the human dummies in the house—placing them in extremely compromising positions. (98-9)

Literary historians are inclined to sigh and wag their heads when they consider the career of Theodore Hook, who died in 1841. Hook was an author, one of the handsomest men of his time, possessing "quick intelligence, and brilliant wit with an unfailing flow of animal spirits." But he threw himself away on "boisterous buffooneries" instead of behaving himself in a manner favored by the literary historians. (110)

Berners Street was bedlam. Carriages and wagons and carts were jammed together, their wheels locked, horses leaping about, and above all, the shriek and clamor of the indignant tradespeople, who began venting their rage on one another. Wagons were overturned and their contents scattered, some of the dignitaries were jostled and insulted, and across the way from Mrs. Tottingham's, concealed behind a curtain in a lodging house, Hook and Beazeley enjoyed the entire spectacle. The madness in the street continued throughout the day and a good part of the night, but when darkness fell Hook departed from the neighborhood, departed even from London, and hid himself deep in the country until public indignation died down. He had written hundreds of letters, signing Mrs. Tottingham's name, and he had lured the dignitaries to the scene by letters which hinted that the Berners Street widow was preparing to dispose of her fortune. (112) [See also]

Matching the Berners Street Hoax for confusion and violence was the Great Bottle Joke, perpetrated by highborn Englishmen in 1749. It began as a discussion in a London club, the topic being human gullibility.

"'I'll wager," said the Duke of Montague, "that let a man advertise the most impossible thing in the world, he will find fools enough to fill a playhouse and pay handsomely for the privilege of being there."

"Surely," spoke up the Earl of Chesterfield, "if a man should say that he would jump into a quart bottle, nobody would believe that."

The Duke said people would too believe it. The wager was made and the distinguished gentlemen set to work composing the advertisement. It said that at half-past six on the following , Monday, at the New Theatre in the Haymarket, a Person would appear who performed several most surprising things. Among other things, the person would enter a common wine bottle in full view of the audience, and while inside it he would sing.

The public stormed the theater at the appointed hour. The place was packed, with hundreds outside clamoring to get in. The audience was patient for a while, but when nothing happened and the stage remained bare, it began grumbling and then yelling. Someone threw a lighted candle on the stage and that started the riot. Every seat in the theater was smashed, everything in sight was ripped to pieces and the debris was carried into the street and burned. (113)

As for E. A. Sothern, he always referred to his practical jokes as "sells." (115)

Sothern was an eternal harassment to tradespeople and his exploits in this direction are best illustrated in an account of his experience with the ironmonger's clerk.

Accompanied by a Mrs. Wood, the actor walked into an ironmonger's shop and said to the clerk, "Have you the second edition of Macaulay's History of England?" The clerk smilngly explained that this was an ironmonger's, and mentioned he name of a neighboring bookseller.

"Well, it don't matter whether it's bound in calf or not," said Sothern.

"But, sir, this is not a bookseller's."

"It doesn't matter how you wrap it," said Sothern, "A piece of brown paper will do—the sort of thing that you would select for your own mother."

"Sir!" shouted the young man, thinking his customer was deaf. "We do not keep books! This is an ironmonger's shop!"

"Yes," said Sothern, "I see the binding is different, but as long as the proper flyleaf is in, I'm not very particular."

"But sir!" cried the young man. "Can't you see that you've made a mistake and come into the wrong shop?"

"Certainly," said Sothern, "but I'm in no hurry. I'll wait while you fetch it down."

The clerk now went to the rear of the shop to summon the proprietor, who came forward and confronted Sothern.

"What is it that you require, sir?" he asked.

"I want," said Sothern calmly, "a small, ordinary file, about six inches in length."

"Certainly," said the proprietor, and giving his assistant a blistering glance, went and got it. (121-2) [Cp. Coyle & Sharpe's "Printer-Painter" put-on.]

In London some years ago a man named Pierce Bottom, weary of jokes about his name, spent several days combing through the telephone directories, seeking people who had "bottom" in their names. He found dozens—Bottom, Bottomley, Winterbottom, Throttlebottom, Greenbottom, Sidebottom, Higginbottom, and so on. He arranged for a dinner to be served in the sub-basement of a London building, and sent engraved invitations to all the "bottoms." Most of them showed up, but Pierce Bottom did not, and the guests found that each of them had to pay his own check. The entree was rump roast. (123-4)

The present Lord Halifax, formerly Ambassador to the United States, was traveling to Bath in a railway compartment, also occupied by two very prim middle-aged ladies who were strangers to each other. The train entered a tunnel and the compartment was engulfed in darkness. Lord Halifax placed the back of his hand to his mouth and kissed it noisily several times. When the train reached his station he arose, doffed his hat, and said, "To which of you charming ladies am I indebted for the delightful incident in the tunnel?" He left them glaring hatefully at each other. (124)

During a brief stay in Paris I made random inquiries touching on the French attitude toward practical jokes. One cultivated Frenchman said the institution is almost unknown. "We," he said, "regard the whole of life as a practical joke, and we do not try to improve upon it." (130)

Let us now go to the other side of the earth and listen to the laughter of the Living Buddha. The story belongs to Dr. Roy Chapman Andrews. Years ago Dr. Andrews went into Mongolia to visit the palace of the Living Buddha, one of the most sacred individuals ever to walk the earth like a natural man. From all over the realm came pilgrims, just to get a look at him, to scoop up handfuls of sacred dirt on which his feet had trod, and to get his blessing.

A short while before Dr. Andrews' arrival, the Living Buddha had imported a Delco electric plant for his palace, but he had discovered a better use for it than the mere lighting of his house. It was his custom to sit at a certain window of his palace and give his blessing, once a day, to the kneeling pilgrims in the yard below. Now he strung a wire from the palace to the courtyard, and ran it across the yard by a series of small posts. As the pilgrims assembled for the daily blessing, they would be instructed to kneel and grasp the wire with both hands. Then the Living Buddha, seated by the window, would throw the switch. The pilgrims reacted with much the same kind of jerks as worshipers at the old-style American camp meetings. And the Living Buddha had so much fun that he ordained three blessings every day instead of just one. (133)

The manager of a Greenwich Village movie house once offended Hugh [Troy] in some way, and Hugh got even. He went into the theater one night and quietly released a dozen moths; these creatures flew directly into the beam from the projection room and stayed there, mottling, the picture on the screen. (135) [Cp. the film Strange Brew.]

[Hugh Troy] is an eminently successful artist and his murals enhance the walls of famous buildings. He doesn't like to be called a practical joker. He considers himself to be a man with an off-beat imagination and a strong inclination to make life more interesting, both for himself and for other people. He believes that his various stunts have done more good than harm—that he has brought excitement and wonderment to people whose lives were otherwise quite drab. (136)

He belonged to a skating club and one day thought up a means of increasing his pocket money. He took a cigar box and painted it and fastened it to the wall near the entrance to the clubhouse. Above it he placed a small sign, which said: PLEASE HELP! It didn't say who or what needed help. Just PLEASE HELP! A surprising number of people dropped nickels and dimes into the box, and Hugh cleaned it out regularly. (137)

Hugh seems to know human nature pretty well. He has definite ideas about art, and the public's appreciation of art. Back in 1935, in New York, the first American showing of Van Gogh was held at the Museum of Modern Art. There was much publicity about Van Gogh in the New York newspapers, but the emphasis was on the lurid character of the artist's life, especially on the fact that he had cut off his own ear. When crowds began flocking to the exhibit, Hugh argued with his friends that most of the customers were sensation mongers rather than art lovers. He decided to test the question. . Using chipped beef, he modeled a grisly and withered ear and mounted it in a blue velvet shadow box carrying a neatly lettered inscription:

THIS IS THE EAR WHICH VINCENT VAN GOGH CUT OFF AND SENT TO HIS MISTRESS, A FRENCH PROSTITUTE, DEC. 24, 1888.

Hugh took the little box to the museum and surreptitiously placed it on a table in a room where the Van Gogh pictures were hung. Then he stood back and watched. The chipped beef ear immediately stole the show—the customers ganged up around it, chattering about it, fascinated by it, ignoring the paintings all around them. (141) [Cp. the surreptitious art exhibit (paintings of electrical outlet covers) perpetrated by Jeffrey Vallance]

[Jim] Moran insists that he does not play practical jokes. "I administer," he says, '''mental hot-foots." (152)

I have written extensively about Moran in the past and in my own opinion some of his mental hot-foots come quite close to being practical jokes. Others, however, are not practical jokes at all, but come under the heading of philosophical investigations. (152)

The double talker avoids bubbling and repetitious sounds, preferring sounds that resemble accepted words. The more closely his sounds resemble accepted words and the more they suggest that there should be words like them, the greater are their effectiveness.

These are sound, proved, double-talk word parts:

urment, istan, antive, ative, ently, incan, apid, avid, istesse, ome, artage, namic, erot, irgan, uctor, onter, vendir, islong, ackid, onate, eton, asia, ogion, izans, orial.

The double talker, once he has learned these word parts, need add only a letter or a short syllable here and there to have a brand new vocabulary, sure to puzzle, harass or dement his victim. But the double talker does not let go a broadside. If he sidled up to somebody and said, "Ristan surmentate, huh? Brackid moistesse zincan lapid," it would neither be double talk nor the mumbles. The hearer would simply laugh.

Instead, the double talker primes his shots with good, hardy words, especially prepositions, articles and adverbs. See how much better it would be to approach a stranger and say, "Napid day, isn't it? There's quite a ristan in the surmentate, don't you think? It was brackid this morning, but it became moistesse later. Do you think the zincan flavid days are here?"

If the stranger is not honest, he will pretend to have understood and remark that he wouldn't be surprised if they were. Once a victim makes a bluff like that, he's fair game. He's on the rise and he can be plinked. The double talker may go on, "I was at a political meeting last night and we discussed Roosevelt's muctor namic. I got so mad I hit a stranger. What do you think of his vendir? I say he has no gonter and that he fomently lacks all trace of lartage. What do you think?" And if the stranger meekly says, "Well, I say yes and no," the double talker comes back with, "Oh, you're one of those pirot Fislong citizens, huh? Well, do you know what I think of your kind? You're just garavids."

Perchance the stranger is honest and says, in the first place, that he doesn't understand. In this event, the double talker simply says, "Oh, a gonate, huh? You don't durnamic in a walage, do you?" and looks for another victim. (173-4)

During World War II, Mr. [Charlie] MacArthur was needed for a special assignment by the Pentagon. He was notified that his job was such that he would need to have a commission, and he was asked to name what rank he would like to have.

"I would like to be a fort," he responded. (194)

I asked Charlie MacArthur what he considers to have been the best all-around practical joke he ever heard about. He spoke of several, but he seemed to favor the story of Waldo Peirce and the turtle.

Peirce, an artist and poet and fabulous character, was living in Paris and the concierge at his hotel became quite fond of him and went out of her way to do special things for him. to make him happy and comfortable. He felt the need to repay her for these kindnesses. He knew the lady was fond of pets, so one day he brought home a present for her, a tiny turtle. She was overjoyed, and spent many happy hours coddling and nursing the creature, and worrying about its diet. Peirce, at the beginning, had no idea of carrying the transaction any further but, as so often happened, his imagination took over. Within a few days after the original gift, he substituted a turtle a size larger. The next day the turtle had grown another two inches in length. Madame was ecstatic. Her pet was flourishing wonderfully under her tender care. She talked about it constantly to everyone who would listen. Day by day the turtle grew bigger until Madame found herself in possession of an enormous and cumbersome creature, almost as big as a baby grand. She still loved the beast, and exclaimed over it and the way it had prospered under her care. But her American lodger could not let matters stand as they were. Now he began reducing the size of the huge turtle, day by day. The lady became frantic with worry: staying up nights, scarcely leaving her pet long enough to permit Peirce to substitute a smaller turtle. She was on the verge of losing her senses when the artist decided matters had gone far enough, and told her the truth. (195-6)

One day a gooney-looking young man showed up on the set and spent the entire day just staring at Mr. McCarey. Finally Mr. McCarey demanded the meaning of this behavior. The young man said he had applied for a job as a director and had talked to Mr. De Sylva. The head of production had sent him out to the sound stage with instructions to study Mr. McCarey's every movement and thereby learn how a truly great director operates. The following morning Mr. De Sylva arrived at his office to find an unshaven, ragged bum waiting for him. The bum said: "Mr. McCarey told me to study you, so I can learn to be a big executive. Mr. McCarey said it'll only take part of one day." (208)

There is an artist living in Hollywood who has a glass eye. That is, he has a couple of dozen glass eyes. Some of them are bloodshot, in varying degrees, to match up with the rest of his hangovers. The others have little paintings on them. On patriotic occasions he sometimes appears with an eye on which is painted an American flag. It is most disconcerting to people who find themselves in conversation with him. This man has a little joke he sometimes pulls in restaurants. Get a hold of yourself now. He'll sit studying the menu, with a waiter standing by. Absently he'll pick up a fork, raise his head, and begin scratching his eyeball with the fork. I don't want to see him do it. I'm even a little sorry I mentioned it. (222)

In the 1860s a man named Horace Norton, founder of Norton College, was introduced to Ulysses S. Grant, and the General handed Dr. Norton a cigar. He didn't smoke it, but cherished and preserved it as a memento of the meeting. In 1932 a Norton College reunion was held in Chicago and Dr. Norton's grandson, Winstead Norton, brought out the cigar, now aged seventy-five. Winstead Norton stood up before the assemblage and delivered a sentimental oration. During his speech he lit the cigar and declaimed between puffs:

"And as I light this cigar with trembling hand it is not alone a tribute to him whom you call founder, but also to that Titan among statesmen who was never too exalted to be a friend, who was . . ."

BANG!

After seventy-five years a Ulysses S. Grant joke paid off. (241-2)

The gadget stores in London do a brisk business, and part of it is export trade. In 1951 it was revealed that large stocks of novelty jokes were being shipped to darkest Africa, where the native witch doctors are finding them most useful in impressing their congregations. Items most popular with the Africans included a cushion that uttered a vulgar noise when sat upon, the exploding cigar, and the ornamental ring that squirts water in the beholder's eye. (242-3)

One of the most successful of the professional ribbers, in the manner of Luke Barnett, is William Stanley Sims, whose specialty is appearing in the role of technical expert at various conventions.

Sims was introduced once at a convention of neurologists as Dr. Worthington Smythe, of Oxford. Impressive with waxed mustache and monocle, he mounted the platform. Looking out over his audience, he noted that several of the doctors were whispering among themselves.

"Come, come!" he objected. "If you American doctors will pay a bit more attention, perhaps your undertakers won't be so busy!"

The audience accepted the reprimand and quiet fell over the hall. Dr. Worthington Smythe asked for a volunteer from the audience, and a noted American neurologist stepped to the platform. Dr. Smythe had him strip to the waist, then began poking at him, inspecting his chest, peering at his navel. Suddenly he turned and picked up a paint brush and swiftly painted a battleship on the man's back. (251)

At Harvard, [Robert] Benchley was studying diplomacy and in the course of the course, he was assigned to write a term thesis on the famous Newfoundland Fisheries case. He turned in his thesis and was promptly talked out of a career in diplomacy; for he had written of the Newfoundland Fisheries case from the viewpoint of a fish. (254)

In time [Eugene Field] became editor of the Denver Tribune. In his office he had an extra chair, for visitors. There was a hole in the seat of this chair of a size to permit visitors to jackknife into it, and the hole was kept covered with a sheet of cretonne. Dozens of visitors, including many prominent citizens of Denver, went through it, and some grew quite indignant. Editor Field, however, mollified most of them by explaining that he could usually judge a man's character from the manner in which he extricated himself from the trap. (256-7)

By all accounts Hughes' skulduggery occupied more of his time than business matters. He would turn up, for example, in a barroom on a rainy day, have a drink or two, and leave his handsome umbrella hanging on the bar. Then he'd retire to a corner and watch the eventual, inevitable theft. It delighted him to follow the culprit to the street where, on being opened, the umbrella discharged posters and banners proclaiming: "This Umbrella Stolen from Brian G. Hughes." (269)

Mr. [Alexander] Woollcott lived, for a time, in an apartment also occupied by Mr. [Harold] Ross and his wife. Hanging on the wall of this apartment was a portrait of Mr. Woollcott by C. L. Baldridge. The painting showed Mr. Woollcott wearing a private's uniform and holding a book, and he was inordinately proud of it. During a period while Mr. Woollcott was away on a trip, Mr. and Mrs. Ross persuaded the artist to paint a second portrait—almost exactly like the first, but not quite. The second portrait had Mr. Woollcott's impressive figure just slightly off balance, almost imperceptibly cockeyed. When Mr. Woollcott finally came home he began studying the substituted picture with a look of perplexity on his face and the Rosses did little to ease his mind. They would say, "What's happening to it? It's moving or something." Mr. Woollcott also knew something was happening to it, but he couldn't make out what, and he'd spend hours staring at it from various angles, sometimes stretching himself on the floor and squinting at it. When at last he found he had been bamboozled, he was furious, for he did not take a joke well.

Once he let word get around among his friends that he wanted the twelve-volume Oxford Dictionary for Christmas. The friends got together and on the happy holiday each one of them presented him with Volume 1. (278-9)

There is a publishing executive who is prominent in New York Society and who is seen frequently in the more fashionable night clubs. He usually carries a supply of cards, specially printed. He looks around the club until he spots someone he knows. Then he bribes a waiter to walk over and place one of the cards in front of his friend. It says: "The management requests that you and your party leave quietly." This gimmick las produced some gloriously undignified scenes. (291)

Norman Ross, distance swimming star of the 1920 Olympics, did some of his training in Lake Michigan. One afternoon he was swimming far out in the lake, off the Chicago beaches. As he made his way in toward the shore, a crowd began collecting. He arrived in shallow water, stood up and yelled to the crowd.

"What city is this?" he wanted to know.

"Chicago!" they yelled back at him.

"Oh, hell!" he called out. "I wanted Milwaukee!"

With that he turned, dived into the water and swam away. (300-01) [Cp. the swimmer running gag in the film HELP!]

Max Schuster, the book publisher, is the champion memo writer of modern times. Most of his memos are written to himself. He starts the day with a supply of paper slips in the left pocket of his jacket. All day long he jots down maxims, ideas, bits of conversation, book ideas, clever phrases, and so on, transferring the written memos to the right-hand pocket of his coat. At the end of the day he studies his supply of memos, and files them away. It is said that he contemplates producing, someday, a huge history of the world's wisdom.

One afternoon Max Eastman was in Mr. Schuster's office. He managed to sneak a slip of paper from the publisher's left-hand pocket. On it he wrote a single word, "Dinkelspiel." Then he slipped it into Mr. Schuster's right-hand pocket.

That night Mr. Schuster stayed up late, puzzling over the one-word memo. He was unable to remember why he had written it. He couldn't go to sleep. He worried about it for days, repeating it over and over to himself, sometimes aloud, confusing people in his office by pacing up and down the floor and saying, "Dinkelspiel, Dinkelspiel, Dinkelspiel." After about a week he gave it up, choosing to lose that bit of wisdom rather than drive himself mad. (305-06)

|