Cobb

Al Stump (1994)

Note: This book is a rip-roaring read but its authenticity has pretty much been obliterated. As the eminent scholar Professor Lebowski has said, "New shit has come to light." Let the reader beware.

(I really enjoyed reading, and re-reading, Stump's book. I should be happy that Cobb wasn't the monster Stump portrayed, and yet, from the point of view of story, I'm disappointed. I AM THE MONSTER.)

"I think I did it for the money." – Al Stump

"To get along with me—don't increase my tension."—Ty Cobb (5)

A few weeks before the book work began, I was taken aside and tipped off by an in-law of Cobb's and by one of Cobb's former teammates on the Detroit Tigers that I hadn't heard the half of it. "Back out of this book deal," they urged. "You'll never finish it and you might get hurt." (9)

Everything went wrong from the start. The Hangtown gunplay incident was an eye-opener. Next came a series of events, among them Cobb's determination to set forth in a blizzard to Reno, which were too strange to explain away. Everything had to suit his pleasure, or else he threw a tantrum. He prowled about the lodge at night with the Luger in hand, suspecting trespassers (there had once been a break-in at the place). I slept with one eye open, ready to move fast if necessary.

Well past midnight that evening, full of pain and ninety-proof, he took out the Luger, letting it casually rest between his knees. I had continued to object to a Reno excursion in such weather.

He looked at me with tight fury and said, biting out the words, "In 1912—and you can write this down—I killed a man in Detroit. He and two other hoodlums jumped me on the street early one morning with a knife. I was carrying something that came in handy in my early days—a Belgian-made pistol with a heavy raised sight at the barrel end.

He looked at me with tight fury and said, biting out the words, "In 1912—and you can write this down—I killed a man in Detroit. He and two other hoodlums jumped me on the street early one morning with a knife. I was carrying something that came in handy in my early days—a Belgian-made pistol with a heavy raised sight at the barrel end.

"Well, the damned gun wouldn't fire and they cut me up the back."

Making notes as fast as he talked, I asked, "Where in the back?"

"WELL, DAMMlT ALL TO HELL, IF YOU DON'T BELIEVE ME, COME AND LOOK!" Cobb flared, jerking up his shirt. When I protested that I believed him implicitly but only wanted a story detail, he picked up a half-full whiskey glass and smashed it against the brick fireplace. So I gingerly took a look. A faint whitish scar ran about six inches up his lower left back.

"Satisfied?" jeered Cobb.

He described how, after a battle, the men fled before his fists.

"What with you wounded and the odds three to one," I said, "that must have been a relief."

"Relief? Do you think they could pull that on me? I WENT AFTER THEM!"

Anyone else would have felt lucky to be out of it, but Cobb had chased one of the mugs into a dead-end alley. "I used that gun sight to rip and slash and tear him for about ten minutes until he had no face left;' related Ty with relish. "Left him there, not breathing, in his own rotten blood."

"What was the situation—where were you going when it happened?"

"To catch a train to a ball game."

"You saw a doctor instead?"

"I DID NOTHING OF THE SORT, DAMMIT. I PLAYED THE NEXT DAY AND GOT THREE BASE HITS."

Records I later inspected bore out every word of it: on August 3, 1912, in a blood-soaked, makeshift bandage, Ty Cobb hit 2 doubles and a triple for Detroit, and only then was treated for the painful knife slash. (10-11)

Finishing his tale, Cobb looked me straight in the eye.

"You are driving me into Reno tonight," he said softly. The Luger in his hand was dangling floorward.

Even before I opened my mouth, Cobb knew he'd won. He had an extra sense about the emotions he produced in others—in this case, fear. As far as I could see (lacking expert diagnosis and as a layman understands the symptoms), he wasn't merely erratic and trigger tempered, but suffering from megalomania, or acute self-worship, delusion of persecution, and more than a touch of dipsomania.

Although I'm not proud of it, he scared hell out of me most of the time I was around him.

And now Cobb gave me the first smile of our association. "To get along with me;' he repeated softly, "don't increase my tension."

Before describing the Reno expedition, I would like to say, in this frank view of a mighty man, that the most spectacular, enigmatic, and troubled of all American sport figures had his good side, which he tried his best to conceal. During the final ten months of his life I was his constant companion. Eventually I put him to bed, prepared his insulin, picked him up when he fell down, warded off irate taxi drivers, bill collectors, bartenders, waiters, clerks, and private citizens whom Cobb was inclined to punch, cooked what food he could digest, drew his bath, got drunk with him, and knelt with him in prayer on black nights when he knew death was near. I ducked a few bottles he threw, too.

I think, because he forced upon me a confession of his most private thoughts, along with details of his life, that I know the answer to the central, overriding secret of his life. Was Ty Cobb psychotic throughout his baseball career? The answer is yes. (11-12)

(Parenthetically, Cobb had a vocabulary all his own. To "salivate" something meant to destroy it. Anything easy was "softy boiled," to outsmart someone was to "slip him the oskafagus," and all doctors were "truss-fixers." People who displeased him—and this included a high percentage of those he met—were "fee-simple sons of bitches," "mugwumps," "lead-heads," or, if female, "lousy slits.")

Lake Tahoe friends of Cobb's had stopped visiting him long before, but one morning an attractive blonde of about fifty came calling. She was an old chum—in a romantic way, I was given to understand, in bygone years—but Ty greeted her coldly. "Lost my sexual powers when I was sixty-nine," he said when she was out of the room. "What the hell use to me is a woman?" (17)

After hitting sprees in other towns, the newcomer was taken aside by McCreary. "You may look like a horsefly out there and you waste too much motion," said McCreary, "but, by God, you show a lot of ability. You might be a natch."

"What's a natch?" asked Cobb.

"A natural—one in a million." (46-7)

The Professor was shocked that the boy had entered into a legal agreement without consulting the head of the family. He felt sorrow that such a promising student was putting university training behind him. Pacing the floor, hands clasped behind him, he gravely said, "This is a fool's act. I ask you to reconsider. You are only seventeen and at a crucial point. One path leads to a rewarding future, the other will leave you shiftless, a mere muscle-worker. I ask you again—reconsider."

"I know it hurts you, but I just have to go," Ty kept interrupting.

"You're deceiving yourself. You'll be surrounded by illiterates and no-goods. Believe me, it's not for you. These men avoid work for play. Some have been known to commit murder and suicide. Fifty dollars a month is nothing to what would come otherwise.

Ty argued that he couldn't help himself: "I signed that contract because I want to find out what I can do. I'm almost sure I can make good. I'll stay out of trouble."

(Frank "Lefty" O'Doul, a slugger for the Philadelphia Phillies and Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1920s and 1930s and confidant of Cobb in the 1960s, used to say, "Ty never could tell this story without crying. For someone who played ball like it was the goddamn Civil War all over again, he was a very sensitive guy.") (52-3)

Bill "Hummingbird" Byron, the funny "singing umpire" of the Sally League, liked to recite self-written poems to batters who stood around waiting for a walk. Byron did this even while a batter was in the box. He embarrassed Cobb with:

You'll never hit the bowler

With the bat on your shoulder.

And:

Only hope for runt

Is take one and bunt.

Cobb told Byron to go to hell. The ditty he hated most went:

Stick the bat up your ass

If you can't show us class. (70)

The use of the ritual scurrility of "nigger" or "nigra" was employed in public by Cobb throughout his life. In his later years, even when black stars Jackie Robinson, Satchel Paige, and Larry Doby finally were admitted to the hitherto segregated major leagues after World War II, his attitude did not change; blacks did not belong on pro ball fields any more than in the white man's parlor. Speaking to friends in private, he regularly dropped "coon," "smoke," "Sambo," and "shine" into his discourse. By inheritance, communality, and disposition, Cobb was a fixed racial bigot. (72-3)

He congratulated Ty for not misbelaving in the city. But the elder Cobb still wanted his son out of baseball. Much underpaid, traded around like cattle, given no security, ballplayers were not respectable people. A Cincinnati newspaper headlined one report, evidently because it concerned a team doing something unique, "BALLPLAYERS GO TO CHURCH, LISTEN TO SERMON."

In West Virginia, one Jim Carrigan was called out sliding into home plate; he went home, got a shotgun, returned, and killed the umpire. According to Cobb in later years, his father read the report's postscript to Ty: "A new umpire was substituted and the game went on, Carrigan taking part in it." Only a few seasons earlier in Lowndesboro, Alabama, umpire Sam White's skull had been fatally crushed by a bat-wielding player.

This was not sport, but work of the devil, said W. H. Ty had been hearing of sin since he was a child, and he had to admit that in Augusta things got rough. (73-4)

This time Cobb was inside the industry to learn more. Within seven years of that date, while playing for Detroit, he would spend time at the local cotton-trading exchange, using his knowledge to buy premium-grade shares in small, then gradually larger amounts. With World War I approaching, he figured correctly that huge amounts of the fiber would be consumed for uniforms. After the war, with cotton short, he would clean up roughly $150,000 on the investment, the first really important money he had seen to that point. (75)

He would limp around when on base with a faked injury, call for the trainer, and after the defense was relaxed streak to the next sack. With umpires, he used the tactic of complimenting them on their keen eyesight and good work, until on a close strike-or-ball decision they would unconsciously favor Cobb. When catchers screamed "Robbery!" Cobb would back up the ump with: "You should run this mug out of here. You're calling a good game." In his mature years the Georgia Peach made a broad analogy: "If you're in a saloon and somebody punches the bartender, who gets free drinks for the next month? Why, the guy who flattens the guy who hit the bartender." (79)

Came August and the season's near end, and Navin, in exercising his option and slightly moving it up, preferred a versatile twenty-one-year-old Tourist outfielder-infielder named Clyde Engle over Cobb. He would have selected Engle but for the intervention of two men. Singing Bill Byron, a Sally League umpire and respected judge of quality, had harangued Detroit's manager, Bill Armour, arguing, "This one is a born hitter—he'll surprise you with all the things he can do. Runs like a scalded dog. Has good instincts. Take him, not Engle."

Armour was skeptical. "I'm told he's got some screws loose, that the team doesn't like Cobb."

Byron admitted this was true, saying, "It's not all his fault. Jealousy is involved. Sure, Cobb's got to be controlled. But as he stands right now he's a hell of a prospect, even this far down in the minors." (97-8)

Injured Jimmy Barrett coached him on the Tigers' hit-and-run, take-or-swing, steal-or-stay signals, Cobb remembered, adding, "We've got a way of swiping New York's signs. See that advertisement on the center-field fence? Well, I'll be sitting next to it in the stands with a spyglass strong enough to pick up warts on their catcher's hands. I can read his signals to Jack Chesbro—he's pitching for them today—on almost every throw. That's where the fence sign—'The Detroit News, Best Newspaper in the West'—comes in."

Barrett went on. "When you're batting, keep your eyes on the letter B in the sign. You'll notice the slots in it open and close. If the slot's open in the upper half of the B, it means I've read their signals from the catcher. It's a fastball coming. If the bottom slot closes you can expect a curve or some kind of drop. One of our boys is working the slots after I give him the word."

"I'm not used to this," Cobb protested. "Can't I get up there and hit my regular way?" It was not the cheating that bothered him; he was feeling a severe case of nerves, and adding another element could hurt his concentration. (107)

His base hits were a useful contribution to a 5-0 Tiger shutout of the Highlanders. But offsetting this was a first-inning headfirst steal attempt in which the catcher's throw easily beat him. That allowed baseman Kid Elberfeld time to slam his knee into the back of Cobb's neck and grind his face into the dirt. "The professional teach," it was called—a naked attack on apprentice ballplayers to discourage stealing. (109)

Within baseline boundaries, access should be equal for offense and defense. The rulebook was vague on the subject. Cobb's interpretation was becoming one of Give me room or get hurt. (113)

A dozen or so Tigers gathered around to cheer while Schmidt handed Cobb the most one-sided licking of his career. In a nothing barred fight, Schmidt hammered away until the smaller man's mouth was gashed, his eyes nearly closed, and he was spattered with blood. Schmidt ended it only when Cobb went down for the fourth time, able only to rise to his knees. But it was noticed by players that at no point did he quit. The loser kept getting off the ground. "You did better than I thought you could," consoled Wild Bill Donovan. (144)

As Cobb analyzed it in a split second, the shortstop had to knock down a spinning ball, regain his balance, turn toward the plate, and plant himself for a longish throw home. Cobb beat the throw by inches. Umpire Frank "Silk" O'Loughlin hesitated, then yelled, "Yerrrrr-safe!" And muttered, "Damned if I see how." (146)

A proposition, not well recognized until then, was stated by Cobb: a defensive play was at least five times as difficult to make as an offensive play. The potential was there for an unassisted fielder's error, a bad throw, a misplay from a bad hop of the ball, the shielding of the ball by he runner, and a mixup of responsibility between two infielders or two outfielders. On offense you had fewer ways to fail after putting the ball in play. Therefore: attack, with the confidence that the odds are with you. Attack, attack—always attack. Once you put the ball in play, the defense has to retire you. Make them throw it. Let them beat themselves with a mistake. (147)

He knocked Bemis back several feet. The ball rolled free. Cobb was still on the ground when an infuriated Bemis, retrieving the ball, began beating him over the head with it. Dazed and bloodied by repeated blows, Cobb tried to crawl away. Not one Detroit player came to his rescue. (148)

One day Schaefer was sent in as a pinch hitter. His recent season's averages had been a paltry .238 and .258. The pudgy Herman faced Doc White of Chicago, one of the best of spitballers, but he doffed his cap and bellowed to the crowd, "Ladies and gents, permit me to present to you Herman Schaefer, the world's premier hitsman, who will now give a demonstration of his marvelous hitting power. I thank you."

The crowd booed. Schaefer then smashed the longest home run seen in Chicago for years. He slid into first base, hollering, "At the quarter, Schaefer leads by a head!" He slid into second with, "Schaefer leads by a length!" At third it was, "Schaefer leads by a mile!" and at home plate he slid in with, "That concludes the demonstration by the great Schaefer and I thank you one and all!" (149)

Even Grantland Rice, his favorite scribe, needed to make an appointment to conduct an interview. "Do you consider baseball a business?" Rice asked him. "If it isn't," said Cobb, "then Standard Oil is a sport." (159)

The Peach's averages at ages twenty-four to twenty-seven were so formidable that in the 1980s his statistics were retroactively examined by researchers, to make sure that recordkeepers hadn't erred. (192)

Unknown to Cobb, the spectator, named Claude Lueker, was crippled. Lueker had no fingers on one hand, only two fingers on the other; he had lost them in an industrial accident. He also was connected with a one-time New York County sheriff.

From his manager's seat, Hughie Jennings watched Cobb's face harden—he knew that chilling expression well—and realized what would happen. It did. Leaping a railing, his star hitter trampled fans to get at the tormentor, sitting a dozen rows up in the stands. He battered Lueker's head with at least a full dozen punches, knocked him down, and with his spikes kicked the helpless man in the lower body. Fans scattered with shouts of, "He has no hands!" Witnesses said they heard Cobb retort, "I don't care if he has no legs!" Umpire Silk O'Loughlin ejected Cobb from the game. (206)

Within hours of Lueker's trip to the hospital, Johnson found himself dealing with outraged Tigers. They had stood at Hilltop Park railings with bats raised against the crowd in defense of Cobb while he hammered Lueker and then fought his way back to the field. Some of the players even had gone into the stands to back him up. Jennings was surprised by his men's emotional reaction. At least 80 percent of his club's roster disliked Cobb and resented him. But now 100 percent of the team was lending him support! Sixteen Tigers telegraphed Johnson a promise that they would not play another inning of ball until Cobb was exonerated. (207)

Cobb quietly pulled the Tigers together at a hotel to say, "Don't do this, boys. I appreciate it but you're only hurting yourselves. I can take it. Go out there and play!' Although facing individual fines and possible expulsion, not a man would back down and cancel the strike. (209)

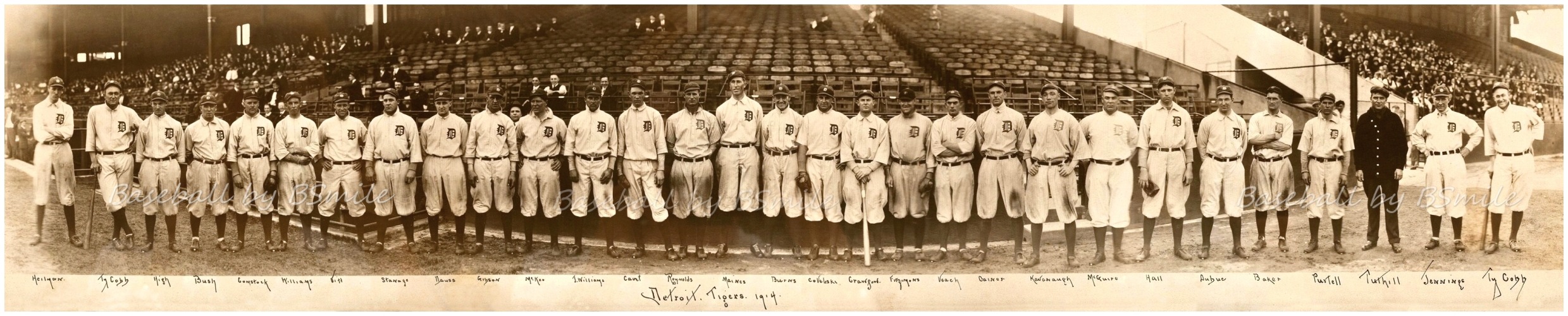

Appraisals that the Peach lacked a sense of humor were all too true. He would, however, now and then, find a laugh in the day's routine. But the funny stuff had to be of his own making. When a Detroit team photograph was taken one day, he managed to be in two places at once without ruining or even blurring the film. The Tigers, posed as a group, formed too long a line for the usual camera to capture, so a panoramic camera was used. A press correspondent's story went, "Cobb was standing fourth from the left, with the lens traveling in an arc from one end of the line to the other. Noticing the rate at which it was going, the prank popped into his head that he could beat the machine.

"So the instant the lens passed him he dashed out and around the rear of the camera and dug out for the other end of the line, like he does when stealing home. What a stunt! He arrived in time to take up a position at the side of Manager Jennings—and in the photo he appears beside Jennings, smiling and as composed as he appears in the fourth place from the right." The "impossible" feat was played in papers across the country under such captions as "Peach's Fabled Speed Positively Confirmed by Camera!" (213-14)

From his early years with the Boston Red Sox, [Tris Speaker] represented a definite challenge to Cobb's all-around domination. A ditty went:

Said Tristram Speaker to Tyrus Cobb,

"Smoke up, kid, or I'll cop your job."

"October will find you a damned sight meeker,"

Said Tyrus Cobb to Tristram Speaker. (214)

So unlike each other in most other ways, the easygoing Speaker and the frenetic, rancorous Cobb formed a lasting friendship. They joined in hunting trips from the southern U.S. to Canada. Their only hard words came, said Grey Eagle Speaker, on a hunt for moose in the Canadian Rockies. T.C. raised his gun to fire, Speaker knocked it away. "That's a lady moose!" Tris objected. "We don't shoot them." Cobb was angry, but the moment passed. (215)

In New York one day he was driving his open two-seater auto through Central Park when a mounted policeman galloped up and arrested him. He asked why. The cop replied, "Never mind, get out of the car." Grabbing Cobb's coat, the man began dragging him out. Doing what came naturally, T.C. descended and punched the cop so hard that the man's helmet flew off and he staggered away bleeding. I'll get ninety-nine years for this, thought Cobb. But then he saw a photographer hiding in the bushes and realized that it was a setup. Press agents for College Widow had planted a fake policeman as a means of creating newspaper publicity. Cobb's fists had spoiled the stunt. (219)

One more tidbit from Lane concerned five-year-old Ty Junior's backing off from a schoolyard fight with an older kid. His father's instructions were: "This boy insulted you and if you don't go out and lick him, then I will lick you." Lane wrote, "Little Ty lived up to the reputation of his dad in a strenuous manner and since then there has been no doubt whatever of his wish to insist upon his rights."

At home at 2425 William Street, in what a curious Lane called an antebellum southern semimansion with a broad veranda encircling it and shrouded by trees, Cobb spoke of why he was constantly on the warpath up north: "I get into a lot of trouble and have made many enemies. But my philosophy is brief. I think life is too short to be diplomatic. A man's friends shouldn't mind what he does or says—and those who are not his friends, well, the hell with them. They don't count." (237)

The "straw hat affair" demonstrated just how much Silas Marner there was in him. A custom had developed in Detroit on Labor Day for the more rabid fans to scale their straw hats onto the field when the Tigers were going well. Cobb ordered the grounds crew to collect and store the skimmers for him. In his book The Detroit Tigers, author Joe Falls told of how Cobb shipped hundreds of hats home to his Georgia farm at season's end, where they were worn on the heads of his field hands and donkeys as protection from the sun. "Each day after the players left;" wrote Falls with a grin, "Ty also would pick up pieces of soap left in the showers. These, too, would go back to Augusta with him—soap for the hired hands."

Concerning the tipping of waiters and cab drivers, a practice then catching on, he was just as thrifty. Upon one cabby's asking for a tip, Cobb snapped, "Sure, don't bet on the Tigers today." (242)

The oddly-named Luzerne Atwell "Lu" Blue, a .300-hitting rookie with the Tigers in postwar years, contributed, "You should have seen other teams before a game ... They'd circle around to cross his path, to give him the 'How are you, Ty? How's the Peach?' Oh, how they sucked around! The idea was to keep him friendly and in no mood to go on one of his wild sprees and beat the hell out of you." (252-3)

Early in 1918, lecturing American patriots on warfare at a rally in Atlanta, he declared, "When you have a winner and loser, it settles disputes over territory. That might not last long. But after the Germans get their asses kicked in the one going on now, you won't be hearing from them for quite a while." (262)

He was recommended for a captaincy. With that arranged, he underwent a physical and a standard psychological test. "Funny result on that," he remembered. "The doctors made the finding that I was normal, but on the shy side. I wasn't an ego type because of the 'shyness.'" That gave the Peach a wry laugh. (270)

In stretching hits he still had no master. Among his more showstopping feats was a play at Boston in which Cobb, at second base, scored on an infield out without an error being involved. This one he conjured up by taking an extra-long lead, so that when the ball was bouncing along—a slow roller to shortstop Everett Scott—he had nearly reached third base. While Scott was routinely throwing out the batter to first baseman Stuffy McInnis, Cobb sped onward, reached home in a tie with McInnis's fairly good throw, crashed into catcher Sam Agnew; deflected the ball with his hip, and was safe. Cobb's postgame analysis: "It took six separate actions by three players to get me, didn't it?"—the shortstop's catch and throw, the first-sacker's catch and throw, the catcher's reception and tag. In combination the ball had to travel some 320 feet, as Cobb had long before calculated. For other fast base runners this would not work. They saw the odds as much too long. As Cobb viewed it, other base runners were not in the right frame of mind to face long odds and beat them. It was a matter of confidence defeating geometry.

New players up from the minors as wartime replacements, who until then had not seen Cobb in action, were amazed. Even some old pros still fell for his sleight of hand. In a Washington game, he caused Clyde "Deerfoot" Milan, the base runner at second, to presume that a seemingly sprinting-in Peach could not reach a humpbacked liner hit to him in center field. Milan thought he saw Cobb running hard, but too late to make the catch. He hesitated, then lit out for third. Suddenly making the catch, Cobb easily doubted Milan off second base. Explanation: T.C. had been pumping his legs up and down, with glove outstretched, depicting a missed catch and practically running in the same spot—applied pantomime. It was all in the deceptive timing. (273)

It became baseball lore that as much as he hoarded money, and as little as he tipped waiters, hack drivers, and Pullman porters, Cobb would share inside dope on stock-market buys with people he liked. According to one of his brokers, Elmer M. Griffin of Beverly Hills, Califomia, his timely advice made considerable profits for retired ballplayers with small incomes or in distress. "I can name you a dozen or so old big-leaguers that Cobb rescued through speculations which he often financed," stated Griffin in 1940. "He'd buy you a house if you hadn't crossed him in the past, if you didn't have the rent and he liked you." (286)

Evans asked Cobb how he wanted to fight. "No rules," was the reply. "I fight to kill."

For forty-five minutes the two punched and gouged it out. Evans was badly cut at the outset and had his nose broken. An orthodox fighter, he found himself up against blows below the belt, rabbit punches, and knee kicks. Evans had Cobb down at one point. They rolled in the dirt, both bleeding. Cobb's eleven-year-old son, Tyrus Junior, allowed to watch, danced about, crying, "Hit him harder, Daddy! Hit him harder!" (297)

The Tigers complained that it had been hard enough to live with him before Ruth came along; now it was becoming impossible. After a Navin Field game where he went hitless, home fans booed loudly. One fan invaded the field to jeer. Cobb kicked him in the stomach, then the groin. And kicked him again. An angry crowd grew so dangerous that Frank Navin ordered an escape car to be rushed to the players' gate. Grouped outside were some two dozen Detroiters leaving the park. A white-faced Cobb walked down a line of fans. To each of them he called, "You want to fight? You want to settle this?" He was alone, no teammate backing him up, while he sought to take on someone—anyone. "I never saw anything like it," marveled veteran Bobby Veach. "All alone like that, he could have been murdered by that crowd."

"If you're all cowards—then fuck you!" was the Peach's last word. He walked to his own parked car and drove away. Detroit had plenty of tough truck drivers and steelworkers, but the insane look to Cobb held them back. (297-8)

There was a bit of consolation for T.C. one July day against the Yankees. He made a racing-in catch of a screaming line drive by Wally Pipp and with Ruth carelessly wandering off second base, continued on to tag him out. He applied a vicious blow to Ruth. "Oh, did that hurt the poor boy?" asked Cobb. "Maybe you should take up pattycake." (307)

Old New York gave him the worst jeering of his career. The Polo Grounds rocked. In a return gesture, seemingly aimed at his teammates for not speaking up in his support over the Chapman-Mays matter, he did not sit in the Tiger dugout. Until game time he sat in a lower grandstand seat, as if inviting physical attack. (312)

A leading historian of baseball, Harold Seymour, years later quoted a pre-1920 sports-journal poem to show how naive the public had been:

For the baseball season is so soaring

High above all, serene

Unaffected by the roaring

For the grand old game is clean! (316)

"Buy Coca-Cola stock for sure," Cobb advised Tris and Philadelphia sportswriter Tiny Maxwell. "Don't sell for a little profit. Forget about it for a few years and live off it when you want to retire." By not taking the tip, Maxwell estimated, he lost out on $240,000 to $300,000 by 1929, when Coca-Cola, despite a national depression, declared three major stock dividends. Speaker did buy in, Cobb told me, and prospered. (324)

Within the next twenty-four months, fifteen Tigers would parade into Navin's office, asking either for a trade or Cobb's dismissal. Complaints ran from the tongue-lashings he handed out, to their disgust at having to supply water buckets in hot weather to Cobb's pet dog. A cur who had wandered in that March had been adopted by the boss. Each player was under instructions to pet the dog at least once a day. Why such a requirement? Veteran players saw symbolism in it—they were a "dog" of a team. When the pet disappeared, Cobb replaced him with an ocelot cub from the South American jungle, who scratched people. (340)

Scouts from other teams, watching a trick played by the Peach on Ruth in New York in September, called it the best such of the season. Haney reported that it began with Cobb, playing center field, whistling a signal to pitcher Hooks Dauss to give Ruth a base on balls when he came to bat. A walk was an obvious move. But Dauss threw a called strike past Ruth. Cobb raced in to bawl out both Dauss and catcher Bassler for disobeying his order. Ruth grinned, thinking it an oversight.

Back in center field, Cobb whistled another reminder. But again Dauss shot a called strike past Ruth. A furious Cobb ran in, stomped around, removed both Dauss and Bassler from the field, and brought in a new battery. After warming up, reliever Rufe Clarke fired a called third strike past an unprepared Ruth. On three straight pitches, Babe had struck out without moving his bat from his shoulder. Cobb doubled up with laughter, rubbing in the ruse. "A once in a lifetime setup play," he called it. "I flattered Ruth with that walk-the-man stuff and he fell for it."

Fred Haney named another Cobb play as the most fiendish he ever saw. In 1920, when Carl Mays of the Yankees had beaned Cleveland's Ray Chapman with a pitch that may or may not have slipped, and Chapman had died of a skull fracture, an outcry against "Killer" Mays had lasted for months. The tragedy marked Mays for life. "We went into Yankee Stadium, three years after Chapman's death," testified Haney, "and Cobb called me aside. He instructed me [as the hitter] to crowd real close to the plate. Then I was to fall down and writhe around if Mays's first pitch was close, a duster. I did so and Ty called for time-out and walked out to the mound. I thought he intended to jump all over Mays. But to my surprise he only said, 'Now, Mr. Mays, you should be more careful where you throw. Remember Chapman?'" Cobb walked back to the plate, shaking his head. Mays was actually trembling ... he was so unnerved that he couldn't get anybody out. We scored five runs off him to beat New York easily." (350-1)

Babe Ruth had something to say. His attitude surprised some people—normally the Babe would just as soon punch Cobb's nose as not—when he spoke from a vaudeville stage in San Francisco: "This is a lot of bull. I've never known squarer men than Cobb and Speaker. Cobb doesn't like me and he's as mean as [censored]. But he's as clean as they come." (383)

Then Ruth and the Yankees came into Philadelphia. Babe strutted to the plate. He waved a handkerchief to the Athletics' fielders, a signal to move back. He swung three times with full power and struck out. Cobb came to bat. He took out a handkerchief and also waved the boys back. Then he bunted, beat it out, and stole second and third. Ruth and the Yankees cussed him each step of the way. (391)

In the early century he had created or improved upon such stratagems as the drag bunt, squeeze play, safety squeeze, suicide or running squeeze, and his specialty, the now-you-don't-see-him-now-you-do delayed steal. The last-named stunt looked next to impossible on paper, but now and then he made it work. In 1927 Cleveland's second baseman and shortstop were playing well away from the base, with Cobb the runner at first. He did not break for second as the pitcher released the ball. Instead he waited until the ball had just reached the hitter and then he made his break. Since Cobb had not started with the pitch, the two infielders were sure that no play was on and relaxed mentally and physically. Cobb was now well on his way to second base. Cleveland catcher Luke Sewell raised his arm to throw, but nobody was covering the base. Sewell had to wait to throw until the shortstop arrived in a rush, and the timing of the toss was so difficult that the ball shot past him into center field. Center outfielder Bill Jacobson's hasty return throw was wild. Cobb scored a run on what had been accomplished by the world's slowest steal. He had never seen this play timed correctly before first using it himself in 1905. "So maybe I invented it," he speculated. (391-2)

Frank O'Doul of San Francisco, the jolly Giants outfielder known as "The Man in the Green Suit," was a guest at Cobb's home that spring. O'Doul's view was, "Ty was a cold fish ... had no sense of humor. About once a year he got off a funny line, like the one about the umpires being blinder than a potato with a thousand eyes. As for his returning to play for one more year, the reason for that move was obvious. Baseball was in his bones—he couldn't stand to watch other guys doing something he had damn near invented." O'Doul didn't need to cite a second motive. Like almost all veteran pros, Cobb was mercenary. O'Doul: "He couldn't leave five dollars on the table." (395-6)

It was the thirty-fifth steal of home base of his career—and the last. Since that June day no one has tied or beaten that number, or even come close. Casey Stengel considered the feat to be the most demanding, dangerous single act in any sport, and informed people that of all of Cobb's records surviving into the 1960s (and the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s) this one was the hardest earned and at least the third-most important. Casey: "Ya got to remember that he went for the plate like a freight train. Ooooooo, he was scary!" (397)

In the late spring of 1929, receiving word that Ty junior had flunked out of Princeton, Cobb had caught a train to the New Jersey campus and called at his son's lodging house. He carried a black satchel. He removed from the satchel a blacksnake whip "and then I went to work on that boy pretty hard," he told this writer. "I put him on the floor and kept it up ... tears and some blood were shed ... but Tyrus never again ... never ... failed in his grades." (405)

Cobb's schedule appeared overfilled, but it was artificially contrived. Beyond golf, polo, shooting game, and reading extensively on world history, he had not enough action to occupy him, and in times of idleness he was bored with life. He was far from ready for the pipe and slippers, although he had a collection of some two hundred briar pipes and smoked them. Time grew so heavy on his hands that he wadded up newspaper and tossed it from a distance into a wastebasket—by the hour. (408)

Atherton neighbors filed other reports of violence. According to the local San Mateo County Sheriff's office, on one occasion Cobb played host at Cobb's Hall to his neighbors. Throughout the evening he drank heavily and during dinner used foul language. One of the ladies objected. He called her an "old whore." She broke into tears. Her husband, a former football player and a husky fellow, invited Cobb outside. The host attacked with fists, at which the guest seized a chair, shattered it over Cobb's bald head, and opened a gash. Blood poured down his face. While Cobb lay on the floor, unconscious, the husband called the sheriff.

"I think I just killed a man here," he reported by phone to a deputy.

"What's his name?" asked the deputy.

"Ty Cobb. He lives at this address."

The officer was not surprised. "Yes, we know all about that son of a bitch. It's a wonder somebody hasn't killed him a long time ago."

No charges were pressed by anyone in the case. (410)

|