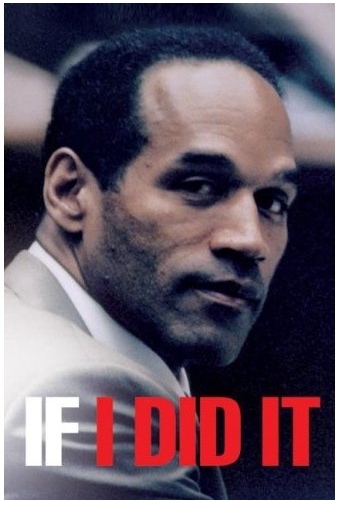

[If] I Did It

O. J. Simpson (2006)

AUTHOR'S NOTE:

If I did it, this is what happened.

I'm going to tell you a story you've never heard before, because no

one knows this story the way I know it. It takes place on the night

of June 12, 1994, and it concerns the murder of my ex-wife, Nicole

Brown Simpson, and her young friend, Ronald Goldman. I want

you to forget everything you think you know about that night

because I know the facts better than anyone. I know the players.

I've seen the evidence. I've heard the theories. And, of course, I've

read all the stories: That I did it. That I did it but I don't know I did

it. That I can no longer tell fact from fiction. That I wake up in the

middle of the night, consumed by guilt, screaming.

Man, they even had me wondering, What if I did it?

For a number of years I was a

pitchman for Hertz, the rental car people. Some of you might

remember me from the television spots: I was always running late,

pressed for time, leaping over fences and cars and piles of luggage to

catch my flight. If you don't see the irony in that, you will.

As I sit here now, trying to

tell my story, I'm having a tough time knowing where to begin.

Still, I've heard it said that all stories are basically love stories, and

my story is no exception. This is a love story, too. And, like a lot of

love stories, it doesn't have a happy ending.

But Nicole didn't come back for several hours. She went down

to the precinct with the cops and they took a statement from her

and had her pose for pictures. It was three in the morning by then.

She was drunk, she'd been crying, and she was under fluorescent

lights without any makeup. Ask me how had she looked.

Did I physically drag Nicole out of the bedroom and push her

out into the hallway? Yes. Did I beat her? No. I never once raised

my hand to her—never once—and if Nicole were alive today she'd

tell you the same thing.

I felt like I'd been

kicked in the nuts, but I handled it. Life throws some shit at you, and you deal with it. I went in and looked in on my kids. They were

both fast asleep. They looked like angels.

Her name was Paula Barbieri, and she was absolutely stunning.

I remember thinking that she looked a lot like Julia Roberts,

only prettier.

I invited them in and got a round of drinks, and I just couldn't

take my eyes off Paula. Unfortunately , she wasn't in the market.

She'd gotten married recently, and it hadn't worked out, so she was

in the process of getting an annulment. Of course, from where I

was sitting, that was a good thing.

That's when my housekeeper came into the room and signaled

to me. I couldn't understand what she was doing. Couldn't she see I

was in the process of falling in love with this gorgeous creature? I

got up and went over. "What?" I said.

"There's a woman upstairs, in your bedroom," she said.

Shit! I'd forgotten all about Miss Hawaiian Tropic.

"Repeated batterings!" I said. "What the hell is that supposed

to mean? What repeated batterings?"

"I know," Nicole said. "I can't believe it either. They're trying

to convince me that I'm a victim of abuse."

"I want to read you something," she said.

"I don't have time for this Nicole."

"It's from my will."

I took a deep breath. "Okay," I said. "I'm listening."

"This is in my will, word for word," she said, and she quoted

directly from the document: "`O.J., please remember me from early

in our relationship, before I became so unhappy and so bitchy.

Remember how much I truly loved and adored you'."

"That's very nice," I said.

"Don't forget," she said. "I mean it."

"I won't forget," I said.

"Promise?"

"I promise."

I wondered whether I was going to

get drawn into Nicole's bullshit and drama for the rest of my life.

When I got back to L.A., Nicole and I got into what I often

think of as our Period of Confusion.

"I thought I warned you about these people," I said. "I've told you a million times: I

didn't want them around the kids."

"They're not around the kids," she said, which turned out to

be a lie. "And I don't know what you have against them. They're

nice people. They're my friends."

"You better open your eyes, Nicole. Nice people don't go

around getting themselves knifed to death."

"It's January. We've got four months before Mother's Day. On

Mother's Day, it will be exactly one year."

"I know," she snapped. "Stop reminding me. I feel like I'm on

trial here."

I know it makes absolutely no sense,

but a lot of the shit we went through made no sense, and I think

my theory's as good as any.

At that point, even an idiot could have told you

that drugs were involved. You don't get mood swings like that from

eating Wheaties.

When the food came, we must have looked just like every

other married couple in the restaurant. We sat there eating, not saying

much, and from time to time I'd reach across the table with my

fork and spear something off her plate.

I was done with that part of my life. I figured

we could have that conversation when she returned to Los Angeles,

but it never happened. A few weeks later, Nicole and Ron Goldman

were dead, and I was being charged with the murders.

But I'm getting ahead of myself again.

So, no. I did not leave the recital "upset and angry," as some

people would have you believe. And I didn't think the Browns were

indebted to me for all the wonderful things I'd done for them over

the years, as other people suggested—though God knows I had

done an awful lot of wonderful things for them. And I wasn't in the

dark mood attributed to me by several people who were at the

recital, including Candace Garvey, wife of baseball's Steve Garvey,

who got on the stand and told the court that I was "simmering" and

looked "spooky." Hell, even Denise testified that I was in a horrible

mood. "He looked like he wasn't there," she said. "He looked like

he was in space."

I was in a lousy mood after the recital.

Usually, when I pick up a golf club, the world disappears—

that's one of the things I like about the sport—but this time, I

couldn't get her out of my head. I remember thinking, That woman

is going to be the death of me.

Nicole's mother, Judy, had left her glasses at the restaurant, and

she'd called Nicole, who called the restaurant, and learned they'd

found the glasses. She was also told that Ron Goldman was just finishing

his shift waiting tables, and that he would be happy to drop

off the glasses at the Bundy condo when he was done. I knew none

of this, of course. None of this had anything to do with my life.

Not then, anyway.

If it was a question of discipline, though, my father took care

of it. And when I say he took care of it, I mean he took care of it. In

those days, there was whuppings, and everyone knew it. You didn't

go crying to Child Welfare or any of that shit, because nine out of

ten times if you got a whupping you almost certainly deserved it.

He told me

to go to my room, and I knew I was supposed to go in there and

wait for him to come in and deliver his whupping. But as I waited,

I decided I wasn't going to get a whupping. I didn't deserve it, and

there was no reason in hell I was going to let him raise his hand to

me. When he came into my room, I told it to him straight. "You're

not going to whup me," I said.

"What did you say, boy?"

"You heard me," I said. "You're wrong this time. You try to

whup me, I'll kick your ass."

It was pretty tense. I had defied him, and he didn't like it one

bit, but he could see that things had changed. I was almost as big

as he was by then, and I knew I could take him, and so did he, I

guess. He left my room without saying a word to me, angry as

hell, and for the next ten years we didn't talk to each other. That's

right: We went ten years without speaking. He would come over,

and hang out, and we even sat at the same Christmas table

together, but we never spoke. And everyone knew we didn't speak.

It was like family lore: The boy defied him, and they haven't spoken

a word to each other in years.

Now picture this—and keep in mind, this is hypothetical: [...]

I reached into the back seat for my blue wool cap and my

gloves. I kept them there for those mornings when it was nippy on

the golf course. I slipped into them.

"What the fuck are you doing, man?" Charlie said. "You look

like a burglar."

"Good." I said. I reached under the seat for my knife. It was

very nice knife, a limited edition, and I kept it on hand for the crazies.

Los Angeles is full of crazies. "Nice, huh?" I said, showing it to

Charlie. "Check out that blade."

"Put that shit back," Charlie snapped. "You go in there and

talk to the girl if you have to, but you're not taking a goddamn

knife with you."

He snatched it out of my hand, pissed.

"You've got to learn to relax, Charlie," I said, then I opened

the door, got out of the Bronco, and stole across the alley.

I looked over at Goldman, and I was fuming. I guess he

thought I was going to hit him, because he got into his little

karate stance. "What the fuck is that?" I said. "You think you can

take me with your karate shit?" He started circling me, bobbing

and weaving, and if I hadn't been so fucking angry I would have

laughed in his face.

Then something went horribly wrong, and I know what happened,

but I can't tell you exactly how. I was still standing in

Nicole's courtyard, of course, but for a few moments I couldn't

remember how I'd gotten there, when I'd arrived, or even why I was

there. Then it came back to me, very slowly: The recital—with little

Sydney up on stage, dancing her little heart out; me, chipping

balls into my neighbor's yard; Paula, angry, not answering her

phone; Charlie, stopping by the house to tell me some more ugly

shit about Nicole's behavior. Then what? The short, quick drive

from Rockingham to the Bundy condo.

And now? Now I was standing in Nicole's courtyard, in the

dark, listening to the loud, rhythmic, accelerated beating of my

own heart. I put my left hand to my heart and my shirt felt

strangely wet. I looked down at myself. For several moments, I

couldn't get my mind around what I was seeing. The whole front of

me was covered in blood, but it didn't compute. Is this really blood?

I wondered. And whose blood is it? Is it mine? Am I hurt?

Nicole. Jesus.

I looked down and saw her on the ground in front of me,

curled up in a fetal position at the base of the stairs, not moving.

Goldman was only a few feet away, slumped against the bars of the

fence. He wasn't moving either. Both he and Nicole were lying in

giant pools of blood. I had never seen so much blood in my life. It

didn't seem real, and none of it computed. What the fuck happened

here? Who had done this? And why? And where the fuck was I when

this shit went down?

It was like part of my life was missing—like there was some

weird gap in my existence. But how could that be? I was standing

right there. That was me, right?

I again looked down at myself, at my blood-soaked clothes,

and noticed the knife in my hand. The knife was covered in blood,

as were my hand and wrist and half of my right forearm. That didn't

compute either. I wondered how I had gotten blood all over my

knife, and I again asked myself whose blood it might be, when suddenly

it all made perfect sense: This was just a bad dream. A very

bad dream. Any moment now, I would wake up, at home, in my

own bed, and start going about my day.

But what the hell—this wasn't really

happening. That hadn't been me back there. I'd imagined the whole

thing. I was imagining it then. In actual fact I was home in bed,

asleep, having one of those crazy crime-of-passion dreams, but I

was going to wake up any second now. Yeah—that was it!

Only I didn't wake up.

When we got to the airport, I checked in at the curb, like I

always do, and watched the skycap tag the bags. A couple of fans

came by for autographs, and I was happy to oblige.

On my way to the gate, I signed a few more autographs, and

when I boarded the plane I shook hands with a couple more fans.

The funeral took place at St. Martin of Tours, a church on the

corner of Sunset and Saltair, in Brentwood. I couldn't have made it

through the service without A.C. and Kardashian. Kardashian led

me to some seats in the second row, behind the Browns, and I

remember that they turned to look at me. They weren't smiling.

Then Shapiro spoke again. "O.J.," he said, "it's just you and

us in this room at the moment, and I don't know if we'll get another

chance like this. I need to know. Is there anything you want to tell

us?"

"No," I said. "I've told you everything. I'm not hiding anything.

You know everything I know, and everything I've told you is

the truth."

Shapiro didn't look real happy about my response, but he didn't

push.

When we got off the phone, I found a legal pad and wrote a

letter, in long-hand, that filled four entire pages. I folded the letter

and put it in an envelope and sealed the envelope and wrote across

the front: "To Whom It May Concern."

I left the room and gave it to Kardashian and told him not to

open it till after.

"After what?" he said.

"Just after," I said. I didn't honestly know what I meant

myself. "When the time comes, you'll know." I'm not sure what I

meant by that, either, but it sounded right.

When we were still a few miles from Brentwood, on the 405

Freeway, heading north, it seemed as if the whole world had turned

out to watch. People were hanging off overpasses, cheering, holding

up signs. GO JUICE!

I remember thinking, When did they have time to make those

signs?

The whole thing took less than an hour. By then we were driving

past the Wilshire off-ramp, and A.C. took the Sunset exit. If the

cops had any doubts about where we were going, they knew now:

O.J. Simpson was heading home.

For a moment, cruising those familiar streets, I suddenly felt

crushingly depressed again. A man spends his whole life trying to

figure out what it all means, trying to make some sense of this business

of living, and in the end he doesn't understand shit.

Like I said earlier, this is a love story, and like a lot of love stories

it doesn't have a happy ending.

I got out of the Bronco and the cops moved in.

Nicole had written:

I want to be with you! I want to love you and cherish you,

and make you smile. I want to wake up with you in the

mornings and hold you at night. I want to hug and kiss you

everyday. I want us to be the way we used to be. There was

no couple like us.

And I'm thinking:

You were sure right about that, Nic.

There was no couple like us.

|