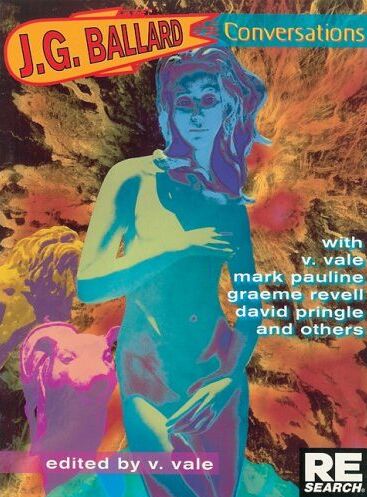

J. G. Ballard: Conversations

J. G. Ballard, ed. V. Vale (2005)

Vale: Bush has said that he talks directly to "God," and that he starts every morning in the White House with a prayer circle with men holding hands—

Ballard: I regard that as an example of what I would call "socialized sociopathy." It's sort of "normalized sociopathy," and it's called "religious belief." That's what's scary: when madness can be recruited—in fact, NEEDS to be recruited—in order to justify one's deepest emotional needs. Because there's no answer to that particular Train of Unreason. It bypasses . . . you're back to "God Told Me To," which is presumably what Mohammed Atta thought as he was crashing his plane into one of the Twin Towers. (18)

I said in one of my books . . . "I see the future as a sort of Darwinian struggle between competing psychopathologies." This is not something that lies in the future; it already began in the 1920s and 1930s. But perhaps it re-emerged, to some extent, with both the attack on the World Trade Center, and then the unrelated (I don't know what the justification was, even to this day) attack by the British and America on Iraq. (20)

Ballard: I don't have a PC actually, but my girlfriend is a keen PC user, a great surfer of the Internet. It's very important to her; it's a social tool, because she has made friends and found people with similar interests. Amazingly, when she meets these people, there's none of that, "Ohmigod, how did I ever get into meeting him?" that you used to get—

Vale: With the old Lonely Hearts Clubs—

Ballard: Right. And some of these sites she's dug up contain accidental poetry that is quite moving. I remember when she first got a PC about six or seven years ago, there were these "telephone booths in the Mojave desert" sites. I can't remember the theory of it, but there was some strangely poetic business about this telephone booth which was still functioning. I can't remember what the exact point of it was, but it became a kind of talismanic object. (41)

Most (how should one put it?) reflective people—readers of broadsheet rather than tabloid newspapers—realize that we were taken to war on a false perspective. And yet it seems to make no difference. It's as if people have unconsciously written off the political process as belonging to a world which they can't influence in any way. That's worrying, because it leaves people sort of falling back on a very different set of resources. (52)

There's almost a deliberate program, especially in America, to keep the people under-educated. (52)

[See John Taylor Gatto)

This "New Religiosity" is a retreat from reason. People are not putting their faith in reason but in a huge irrational system built around various supernatural beliefs. And this retreat from reason is taking place at the same time that the United States has developed these super-technologies that are really changing our lives. It's an extraordinary development that someone working on the forefront of advanced science and technology should on Sunday put on a different hat, go off and listen to fable spun about a Palestinian resurrection cult 2000 years ago. It's bizarre, in a way. (55)

But what is interesting is: when she started meeting these people face-to-face . . . she got on well with people whom she had only known as glorified pen-pals. That's very unusual. Usually you go, "Ohmigod—how did I ever share so many letters with this strange person?" That hasn't happened. It's almost as if there's something about the Internet which is filtering out people who are not going to get along with you. It's most peculiar.

Actually, I'm wondering if it isn't so much that, as the fact that given a sort of "distributed personality" across the whole range of Internet contacts, when you meet the actual person, you are only bringing to bear a small portion of your actual personality, and you're quite satisfied. Whereas in the old days when you met a pen-pal and you were pulled up short and thought, "Oh god, how are we going to get through this strange meal together?" because you were expecting a complete meeting of minds, now you only meet that small portion of the mind that's being offered across the Internet bridge.

I observe the Internet over my girlfriend's shoulder; I don't want to get too close because it might suck me in. (63)

If you go to a website like the Encyclopedia Britannica, the information on the whole is fairly reliable. If you want to know the population of Venice, you can rely on the Britannica to give you a fairly (or approximately) accurate answer. But you can't rely on the Net . . . at least, that's my experience. (79)

[Actually: "According to a study by the journal Nature, Wikipedia . . . is almost as accurate as the online Encyclopaedia Britannica, at least when it comes to science. Nature took stories from Wikipedia and Britannica on 42 science-related topics and submitted them to experts for review. The experts were not told which encyclopedia the stories were from. "The exercise revealed numerous errors in both encyclopedias, but among 42 entries tested, the difference in accuracy was not great: the average science entry in Wikipedia contained around four inaccuracies; Britannica, around three," according to Nature."]

The paradox is that NASA is now a huge obstacle in the way of space exploration. It originally got off to a tremendous start landing men on the moon, but now it's become a kind of public-relations-driven corporation that needs manned space flights in order to justify its huge funds. But as long as we have manned space flight dominating the show, we're not going to get any real advances in space exploration, because the job of leaving this planet is prohibitively expensive. If they dissolved NASA and replaced it with some successor organization committed to unmanned space flight, there'd be an enormous expansion of interplanetary activity of all kinds. Dozens of probes would be going off to the planets; the Space Age would really begin. But it won't happen, of course, because NASA is deliberately, willingly, and willfully trapped in this Buck Rogers dream that it's constructed around itself. (93-4)

The reasons for Japan's attack on America have been rather obscured over the years. In fact, the Japanese were faced with an oil boycott by the United States and were desperate to do something about it. (96)

You do become sensitive to random noise as you get older. You want nothing to change. It's a way of slowing down time! (111)

Vale: There's another way to thwart those surveillance cameras: start a fashion movement in which everyone wears ski masks that completely cover their faces, and big hats that shade people's faces from recognition. . . .

Ballard: That might be the key to our survival: clownish behavior! To survive, people will dress up in the most outlandish outfits; everyone will become a quick-change artist. . . .

Vale: . . . Yes, that's our future: we'll all become pranksters, clowns, and camouflage artists.

Ballard: That may be necessary. I can see it happening.

Vale: Multiple identities.

Ballard: Eccentric behavior, highly imaginative eccentric behavior, may become a survival imperative. The opposite of conformism. (125)

Ballard: Does that mean there's been an exodus of gays from San Francisco?

Mark Pauline: So many people are dying that someone who works for a funeral home brought a dead AIDS patient over to our shop to show us. We looked at this dead man and were like, "Hmmm . . . " (132)

Punk was rather like taking up bull-fighting in Spain. It was something for a working-class kid with no hope and nothing but his own sort of courage. . . . It's his one way to make it to the big time. If you're a working-class kid from a rough council estate in the North, you just buy a guitar and you're ready to go! Whereas writing a novel requires a framework of literacy and a whole knowledge of fiction and literary culture in general. You can't just sit down and write a novel. Plus, there are the circumstances of getting published and all the rest of it. So all the creative vitality of today, I think, goes into popular music. (143)

I have absolutely no feeling for the "psy" phenomena—the supernatural, telepathy. Completely skeptical about it all. It's all bunk, that stuff, you know. I'm constantly surprised by the degree to which extremely intelligent people have actually shown more than just a passing interest in these topics. It constantly astounds me. (147)

Mark Pauline: What sort of control do you retain in your [Empire of the Sun film] contract?

Ballard: None, nothing, nothing.

Pauline: Is there even a clause for them presenting the finished script to you for approval?

Ballard: No. The Warners' contract is longer than my book—it's a huge document, which I had to get notarized by a vice-consul at the American Embassy. (151)

I keep thinking about how to do something different with my life— make a radical change . . . but it gets more and more difficult as you get older. At least it does for me. When my kids moved out, they left a huge vacuum behind. But one tends to fill that vacuum in small ways. When I was bringing them up I kept looking at the English rain sledding down, thinking, "Well, when they're all grown up and happily settled, I'll be able to take off for San Francisco or Tahiti or wherever." But when the opportunity came, television and a nice whiskey and soda in the evenings seemed to be what one's destined for. (154)

You work out of your own obsessions . . . that little universe inside of you. This is probably a bad thing. One no longer has the kind of instinctive need to move around the world and have new experiences, that you had in your twenties and thirties. It's a problem, that, and god knows how to solve it. (154, 156)

[William S. Burroughs] seemed to have—I don't know if it had something to do with the gay world—this sort of transience, this relentless traveling: Tangier for two years, Paris for two years, London for two years, and then somewhere else, always shifting. As these people don't breed children, they don't have to put down roots anywhere—whether it's part of that, I don't know. I envy him that, actually. Just being realistic, I couldn't imagine myself going to live in Mexico City for two years for no particular reason. (157)

When somebody tells you that half the archers at the Battle of Agincourt were suffering from dysentery, as I believe is true, and weren't even wearing their trousers as the French knights charged towards them into a hail of arrows, it gives a different impression of this battle and what's involved. And the same is true of almost anything. The inside story is always much more interesting than the story we are first given. (180)

I look back on my life's work. I reached my 60th birthday in November [1990]. A very significant turning point. Curiously, I didn't feel 50 at all [when it happened]. Forty I didn't even notice, possibly because there were youngish children around. I was waiting for 50 to hit me between the eyes because it's such a famous date. But 60 came up and absolutely floored me. I still haven't recovered.

I look back and think, "What have I done? Written all these books." It's not the books, but this imagination churning away. Wouldn't it have been more sensible to build a bridge or something? One starts taking it for granted—all these castles in the air. Maybe that's why I'm starting to turn back to more naturalistic sorts of fiction. [But] old habits die hard. (188)

Lynne Fox: Somehow in your novels, whatever the setting, it is always desert light and an emptiness where each thing is significant.

Ballard: Yes. I don't know why that is, because I've hardly ever seen the desert in reality. On the way back from China we stopped in Egypt for a while, going through the Suez Canal. I think there are landscapes of the mind that tap something deep in your central nervous system.

We obviously inherited through our genes a whole visual apparatus—grids and patterns are laid down in the brain. A human baby takes a long time to cope with its world, though recent research seems to suggest that babies of even a few hours are beginning to activate these pattern-recognition systems in their brains which are triggered off by everything—the mother's presence, a smell, a smile. They are beginning to assemble all the basic building-blocks of perception

But I assume that the interest that deserts hold for a lot of people, is in some way connected with this inherited perceptual apparatus that assigns a certain special value to flat landscapes with isolated objects. Purely on the level of the nervous system—I'm not thinking of anything mystical. The brain, presumably as part of its pattern of recognition systems that are passed on through the genes, is waiting. It gives the baby a clear field of view, and it is instructed, as it were, through the wiring diagrams to notice especially some isolated object that comes into view. It's probably going to be your mother.

I imagine that the appeal of certain landscapes like deserts is in some way connected with the basic perception of objects in our primary recognition of the world around us. Something of that is being tapped when we respond strongly to certain kinds of landscape. We recognize that this is a moment of primary recognition. (190-1)

There are a lot of errors that crept into all the printed text of these stories and book reviews—particularly in the Guardian newspaper, which is famous for typo's [sic]. (256)

How is Pranks! doing? It's a wonderful, marvelous book. It's much more than a book about practical jokes—it's profoundly subversive, because it's a whole new way of looking at reality. It's amazing. (284-5)

After signing dozens of books at a book signing, you start having to work hard at remembering who you are. Just try, experimentally, writing a word—any word—over and over and over. Deterioration sets in. (290)

In New York City, Channel 23 seems to put on what is very close to hardcore movies in a Blue Velvet type of set—in a sort of sleazy, tenth-rate hotel. By habit I watch TV with the sound off. And this woman was talking to the camera while slowly opening her legs; I thought: "What's going on here? This is amazing!" And then an ad for a dating service came on. (305)

(See also J. G. Ballard: Quotes)

|