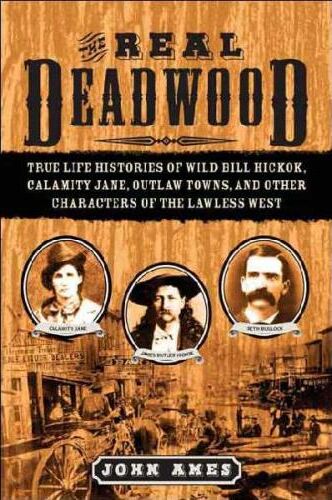

The Real Deadwood

John Ames (2004)

The concentration of money in cow towns drew gamblers, thieves, "soiled doves" (prostitutes), flimflam artists—and killers, both the professional and the impulsive amateur. The gunfighter was a product of the Civil War and its brutal lessons in "easy-go killing." (3)

No matter how wide-open those early cow towns might have been, historians and frontier buffs alike agree: there was no hellhole quite as hellish as a gold-strike camp. "[Wyatt] Earp said gunmen in Deadwood were as proficient as in any western community, except possibly Tombstone." And both were gold-strike towns. (4)

After the war, however, railroads began a vigorous campaign to lure Americans, and especially naive immigrants, to the Plains. "Rain follows the plow!" insisted advertisements, promoting the widely accepted (and remarkably silly) belief that merely cultivating the soil would somehow stimulate rainfall. (11)

It's widely reported that a parade greeted the arrival of Wild Bill Hickok and Charlie Utter's wagon train in Deadwood in July 1876. But all those cheering men weren't welcoming Hickok. They were hooraying the arrival of Deadwood's first batch of whores, who were traveling in Hickok's party. (13)

Pregnancy was only one of the risks that prostitutes (soiled doves, or "sporting girls") faced. There was also the risk of STDs (sexually transmitted diseases), physical abuse from customers and the hired help, and an alarmingly high suicide rate. The working life of a typical frontier prostitute was only a few years.

Contraception was fairly well understood by the 1870s (the birthrate fell from slightly over 7 children per couple in 1800 to only 4.4 by 1880). But the methods were notoriously unreliable. Condoms made from the lining of sheep intestines were available in the 1700s. They were not preformed to fit the man's penis, but rather, simply shaped like a handkerchief and held in place during the act. James Boswell, Dr. Johnson's biographer, complains bitterly about them in his comically frank London Journal.

Worse, they cost $1 apiece (around $25 today), which usually meant they were washed and used over. Because of their pleasure-robbing thickness, they were more commonly used in England and Europe than in the U.S. Particularly in frontier whorehouses, American males insisted on riding bareback."

Thus, the onerous reality of birth control fell to the woman. One device in widespread use was a contraceptive sponge with a thread attached so the sponge could be easily removed. Another method was douching with spermicides such as alum or zinc sulfate. "Female syringes" were sold for this purpose.

Perhaps most widely used was the pessary, or "pisser," a precursor of the modern diaphragm. Made of wood, cotton, or sponge, the pessary was sold as a medical device for correcting a prolapsed [out of place] uterus." But most women knew its real purpose even if men never caught on.

These methods varied in their effectiveness. But given the frequency of intercourse (a former .. Deadwood prostitute reported servicing twenty-eight men in one night), failures were common. Which might help explain why one in six pregnancies was aborted by the 1860s.

By the time Deadwood Gulch filled up, at least twenty-five different chemical abortifacients were widely available and openly sold under such euphemistic names as "infallible French female pills." Marc McCutcheon notes that surgical abortion was available by 1861 and cost $10 to $100. Unfortunately, many surgeons of that day still scoffed at Joseph Lister's insistence on the importance of disinfecting operating rooms and surgical equipment and many women died of postoperative infections. (24-6)

"Gone to bury my wife; be back in half an hour," read a note on the door of a prospector's shack in the 1860s, pretty much saying all that needs to be said about gold fever. (31)

Some folks with money to invest, but no common sense about mining, showed up at the goldfields hoping to buy an existing claim. It was child's play to covertly plant a few bright nuggets to catch their eye.

Some of these swindles were too outrageous to believe, and yet court records prove they worked. One miner planted not only gold but a cut diamond—and sold his claim! Another used the added lure of "fresh fruit" to sell a played out claim. He tied oranges, by small threads, to the branches of some nearby trees. The greenhorns he fleeced had no idea oranges weren't native to the area—or they were too gold-struck to think rationally. (41-2)

The Civil War bred unprecedented carnage and suffering. Many of those veterans on both sides were also afflicted with "soldier's heart"—that era's euphemism for post-traumatic stress disorder. Today, millions of Americans rely on psychopharmacology to help maintain normal behavior. Frontier Americans hadn't yet discovered Prince Valium and his descendants, a point made poignantly clear in Deadwood's portrayal of an emotionally disturbed Calamity Jane. (49)

Bullock logged an interesting journal entry while exploring Yellowstone: "Numerous hot hell holes, all smelling of sulfur ... Will recommend this country for religious revivals when I get back. Hell is sure close to the surface here." (64)

But sadly for the millions who would suffer and die because of his treatments, [Benjamin Rush] also believed that many contagious diseases, such as the terrible killer yellow fever, were caused by "noxious miasmas," or pockets of poisoned atmosphere."

For decades, because of Rush's widely disseminated ideas, cities like New Orleans fought the plague with artillery cannons aimed into the sky to "blast apart the miasma." But the miasma was not such a foolish theory in the pre-microbial world. They knew about epidemics, of course, and even learned that rodents and birds could spread diseases. But somehow the germ theory gained slow acceptance in America despite the proof of "animalcules" (microbes) as early as 1677. The atmosphere was the focus of evil, in Rush's view, not invisible pathogens. (82)

"The abolishment of pain in surgery is a chimera," scoffed Dr. Alfred Velpeau, a professor of medicine in Paris, only six years before the first demonstratin of etherized anesthesia. "It is absurd to go on seeking it. Knife and pain are two words in surgery that must forever be associated in the consciousness of the patient." (85-6)

Patent medicines were useless nostrums often laced with alcohol (Lydia E. Pinkham's Vegetable Compound, twenty percent alcohol and the most successful patent medicine of all time), opium (Tott's Teething Cordial, "Satisfies the Baby, pleases the Mother, gives rest to both"), and cocaine (Casseebeer's Coca-Calisaya, "Each tablespoon represents about one gramme of the best Peruvian Coca Leaves"). Wildly hyped as cure-aIls, they were the nation's first real mass-market advertising success.

However, "patent medicine" was a misnomer. Usually, only the shape of the bottle or the design of promotional material was patented. A patent on the actual formula would have revealed the drug and alcohol content—and many of patent medicines' most loyal customers were temperance ladies. (88-9)

The Cheyenne, cousins and battle allies of the Lakota, once painted their arrows blue to symbolize a sacred lake in these Black Hills. They called the hills simply Wakan Tanka, the "Great Mystery." (93)

Teddy [Roosevelt] got off to a shaky start in the cowboy arts. On one of his first cattle drives he attempted to "haze" the beeves with the shout, "Hasten forward quickly there!" The cowboys cracked up. (105)

A Pinkerton recorded this description of the Sundance Kid (Harry Alonzo Longabaugh): "32-5 ft 10.175—Med. Comp. Firm expression in face, German descent Combs his hair Pompadour, it will not lay smooth." (107)

Many who are tired of the old tintype cliches would like to know the real truth about Calamity Jane. Maybe it's just this simple: she was the American West's greatest bullshit artist ever. And that's saying an impressive mouthful.

She lived an interesting if hard life, and there seems little debate on the matter of her riding and shooting skills—she was "death to the devil." She was also another one of those courageous, compassionate unpaid nurses Deadwood produces in a pinch.

But the truth is, nobody knows much for certain about her—even Calamity's most scholarly biographer admits that right up front. Once the dime novelists and theater agents had latched onto her, Calamity Jane probably realized nobody wanted the truth. They wanted what we call today "the juice" and what people in Jane's era called "tossing in another grizzly."

Almost everything about Calamity Jane, from her real name and birthdate to her true marital status and relationship with Wild Bill Hickok, is in a confused moil because of Jane's "stretchers." The fact that we have only her word she was even married or ever a mother, for example, doesn't mean she wasn't. And that's the genius of her system if that's what it was: give the greenhorns just enough to build their damn hog-stupid legend on but not enough to prove "The White Devil of the Yellowstone" (another flashy name she gave herself) was an out-and-out bullshitter. (126-7)

Calamity Jane's hoodwinking of a willing press and public is funny and admirable not scandalous. Who can blame her for taking what was offered? She was one of the first masters of spin and of image control. Even today, naive writers report her manufactured stories as fact, never realizing they have been had by the best in the West—Calamity Jane, gold camp nurse and bullshit artist extraordinaire. And while she may have dressed like a man, here was a woman indeed. (138)

Custer's wife, Libbie, deeply in love with her dashing and famous soldier husband, nonetheless confessed, "I do not recall anything finer in the way of physical perfection than Wild Bill." Ellis Pierce, the Deadwood Gulch doc who helped Colorado Charlie wash the blood from the dead Hickok's hair, said, "Wild Bill was the prettiest corpse I have ever seen." (141)

The return of wagering to Deadwood has created a second boom, especially as much of the revenue funds historical preservation. But there's also been a joke going around since gaming returned about how lawyers have raised more buildings in Deadwood than contractors have.

It seems that South Dakota state law limits the number of gaming devices (slot machines, etc.) to "30 per building." That has led to some creative decisions by the gaming board as to what constitutes a "building," reported Scott Randolph in the April 13, 2004, issue of the Black Hills Pioneer. Decisions that might leave most building inspectors astounded. Such as a recent ruling that a casino was actually two "buildings" because ground radar showed fragments of old foundations under the casino! (161-2)

|