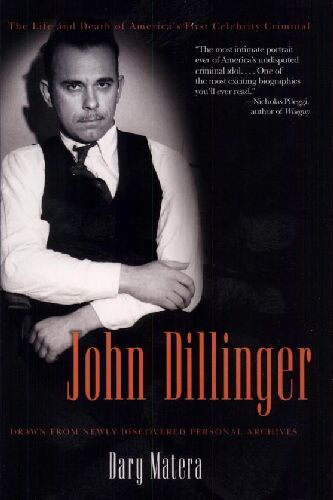

John Dillinger: The Life and Death of America's First Celebrity Criminal

Dary Matera (2004)

When all of the known facts about Dillinger are dragged into publicity, it will be found that no desperado in America can approach this bad man's record ... There are enough angles on [his] tribe and its history to write a great big book. —Captain Matt Leach, Indiana State Police, 1933

That's precisely what Joe Pinkston and Tom Smusyn did—and it took them nearly a half century. When Pinkston died by his own hand in 1996, he left behind an extraordinary, eighteen-hundred-page gold mine of edited research that covered every aspect of John Dillinger's life. (3)

Suddenly, John Jr. slithered away, leaving a stunned Aulls holding an empty coat. A no-nonsense time in law enforcement history, the two officers thought nothing of pulling their weapons and firing a total of seven shots at a fleeing young man who had done nothing worse than having a handgun. Had either Aulls or Hodges been better shots, John Herbert Dillinger would have been a forgotten footnote in history. (18)

Porch lights started snapping on as concerned neighbors fumbled for shoes and shirts in order to dash out side to see what was going on. Morgan instinctively gave the "Masonic Grand Hailing Sign of Distress," hoping someone would recognize the gesture and come to the rescue. (Hands up in the air like a football referee signaling a touchdown, only with the elbows bent to form more of a square.) (23)

Dillinger was further enraged by Singleton's lighter sentence and vowed to keep a promise he made before the verdict that if his accomplice got off easier, "I'll be the meanest bastard you ever saw when I get out." (26)

Superintendent A. F. Miles, a caring man who stubbornly held on to the ideal of rehabilitation, would always remember the almost refreshing frankness of inmate 14395. "I won't cause you any trouble except to escape," Dillinger admitted in his first interview. "I'll go right over the administration building." (27)

The three-member parole board, which included the then-Indiana governor Harry C. Leslie, took one look at Dillinger's thick file and sent him back inside. Hearing the news, the young hopeful merely shrugged and, according to a newspaper reporter, asked to be transferred to Michigan City because they had a "better ball team." (31)

Johnnie D wasn't going to wait for any over-observant clerk to start screaming this time. He and Shaw entered with their guns drawn. Dillinger announced the stickup and began emptying the cash drawer at the soda fountain. Shaw dashed to the back to loot the main register. While in the process, Shaw became uneasy and looked up to see everybody in the place staring at him with their hands raised. He ordered them to pirouette. Seconds later, he glanced up and saw them facing him again. "Turn around!" he screamed, growing angrier. A few moments after that, they were peering at him again. The young robber finally figured out that Dillinger, across the way at the front of the store, was telling the terrified people the same thing. The two bandits were spinning the hostages around like tops. (47)

On the way, they stopped in Fort Wayne to drop in on another Indiana State vet, a dangerous fellow named Whitey Mohler. A career criminal convicted of killing a Fort Wayne police officer, Whitey had devised an ingenious way to beat his life sentence. He contracted a mystery illness that turned his skin yellow and made him burn with fever. Baffled prison doctors finally stamped it as tuberculosis and shipped Whitey to a TB sanitarium. There, he made a not-so-miraculous recovery achieved by the sudden lack of shellac in his body. He'd been drinking the potent stuff at the furniture shop in Michigan City. (51)

Returning empty-handed, they decided to hit the "Bide-A-Wee Inn," a roadhouse on Burlington Drive and Twelfth Street in Muncie that specialized in barbeque. After pointing out the place, Copeland was dropped off a mile away because he'd dined there before and might be recognized. The robbery went without hitch until they were backing out of the door. Two young couples were coming in, and Dillinger decided to pinch the breast of one of the ladies. Her angered boyfriend lurched forward, and John Jr. struck him across the mouth with his gun barrel. This time, to Dillinger's disappointment, there was no shower of teeth. (55)

Shockingly, young Margaret was the only person in the bank. The other employees were literally out to lunch. Miss Good raised her hands, but Dillinger calmly told her to put them back down. He didn't want to attract the attention of "citizen variables" outside. (56)

The postmasters of Mooresville and Maywood had agreed to make tracings of all mail sent to the Dillinger family—civil rights abuses that wouldn't be tolerated today. [HAHAHAHAHA] (68)

Reporter Red Biery was already outside when the fun started. He was crossing Main Street when the first gun went off, prompting him to duck behind a parked car. "Good men are scarce," he cracked later. "I decided to preserve one." (71)

On September 6, Lloyd Rinehart, assistant manager of the Massachusetts Avenue State Bank on 815 Massachusetts Avenue, was sitting at his desk chatting on the telephone when he heard someone say "This is a stickup! We mean business." It sounded so phony he didn't even glance up or interrupt his conversation.

"Get off that damned telephone," John Dillinger snarled like a crazed monkey from a perch atop a metal cage. Rinehart lifted his eyes and discovered a man pointing a .45 automatic into his face. (76)

Although Vinson, Crouch's cousin, had been annoyingly nervous, it wasn't his first bank job. He'd pulled off at least two, along with some lesser hits on stores and crap games. He was arrested in Haines City, Florida, the previous year, but a squabble between police departments in Haines City and Indiana over who would pay the costs of his transportation resulted in frustrated Florida officials kicking him loose.

Surprisingly, it was the cooler veteran Crouch that messed up in the aftermath. Flush with money, he bought a Chicago tavern, then wined, dined, and married a seventeen-year-old girl. By December, the big spending, highly visible crook was behind bars. In contrast, Vinson took his eight grand and laid so low he was never heard from again. (77)

In Dayton, the various interrogators all noted that Dillinger appeared in good spirits and was oddly unconcerned about his sudden misfortune. Admiring the detectives' bulletproof vests while being booked, he asked Gross if they were "any good."

"We don't know, but we feel a little safer with them on," Gross responded. "What do you think?"

"I put three steel-jacketed slugs through one not so long ago," the robber said with a devilish grin as Gross's blood chilled. "Only in practice, of course," (81)

While a beefed-up force would no doubt help stem the state's criminal tide, it remained debatable if such expanded power should be allowed to fall into the hands of the state police captain, Matt Leach, a man whose behavior was becoming increasingly bizarre. Leach ordered his troopers to squeeze the still-trembling Ralph Saffell, the unwitting boyfriend of Typhoid Mary II, little Mary Kinder. A near-hysterical Saffell argued that he was a hostage, not an accomplice. An unsympathetic Leach tossed him behind bars anyway, dubbing him a "material witness." Leach then had his personal goon squad rough up Kinder's parents and sister Margaret. Angry over the bullying, Margaret clammed up, earning the nickname "Silent Sadie." Leach charged her with vagrancy and tossed her into the slammer with Saffell. (100-01)

On the evening of October 14, the reunited escapees waltzed into the Auburn, Indiana, police station at Ninth and Cedar streets, confronted the two officers holding down the fort, and announced a stickup. The stunning statement made sense to the crooks—they were looking to boost their arsenal. Given the keys to the taxpayer-funded gun lockers, the pair scooped up a Thompson submachine gun, two .38s, a .30 caliber Springfield rifle, a Winchester semiautomatic rifle, a shotgun, a .45 Colt automatic, a Smith & Wesson .44 revolver, a .25-caliber automatic pistol made in Spain, a 9mm German Luger, three bulletproof vests, and a large supply of ammunition.

Charlie Makley, covering the door, helped load the weapons into the getaway vehicle. The bewildered cops were locked in their own holding cell, giving Dillinger and Pierpont a brief moment of satisfying revenge. (109)

A few days after Leach's dizzying pronouncements, Dillinger and Pierpont walked into the Peru, Indiana, police headquarters just after 11 P.M. and got the drop on two cops, a security guard, and a nightshift cook who had wandered by to chat. Pierpont, seemingly on the same alien wavelength as Captain Leach, snarled, "I haven't killed anybody for a week now. I'd just as soon shoot one of you as not. Go ahead and get funny!" While the duck-footed Pierpont was perfecting his madman act, Dillinger calmly emptied the gun cabinet, dumping the weapons in a large robe spread on the floor. The haul included two fully loaded Thompsons, a tear-gas gun, three rifles, two sawed-off shotguns, a 12-gauge automatic shotgun, a .32-caliber automatic pistol, a .45 automatic pistol, five .38 Special revolvers, 9 bulletproof vests, 10 magazines of machine-gun bullets, 3 badges, 2 boxes of shotgun shells, and a pair of handcuffs—perhaps for more bedroom fun with the awaiting Marys. (112)

Backing out of the bank, Dillinger, in "boisterous spirits" witnesses would recall, said, "Boys, take a good look at me so you will be sure to know me the next time you see me!" (115)

The Greencastle heist was the first to kick off what would soon became a disturbing double-whammy for insurance companies and government regulators—thieves robbing banks and crooked bankers grossly inflating their losses. (116-17)

With each new robbery, the Indiana legislature opened its treasury, giving Captain Leach pretty much anything he wanted. His troopers received beefed-up cars, submachine guns, and steel vests—all thanks to John Dillinger. In addition, a law was passed empowering all Indiana sheriffs to deputize anyone willing to arm themselves against The Terror Gang. This created a rash of dangerous, rag-tag roadblocks across the state, every single one doing nothing more than scaring children and hassling the innocent. The highly recognizable Pierpont boasted that he passed through such yahoo operations more than thirty times. (117-18)

Uncle Sam was tossing the federal bucks around as well. The biggest deployment came from the United States military. On October 26, a force of 765 National Guard marksmen were stationed at armories throughout Indiana and placed under the command of the state police. The Guard promised to stand by with troops, tanks, poisoned gas, and airplanes. Feeding off his boss's [J. Edgar Hoover's] paranoia, Leach underling Al Feeney requested that Halloweeners refrain from costumes and activities that might lead them to be mistaken for gangsters—as if a three-foot version of Johnnie D was going to confuse Indiana's crack law enforcement agent.

The police hysteria, seen in dozens of historically preserved memos exaggerating The Terror Gang's activities, numbers, and strength, was not universally shared by the public. In a time of bank closings, mortgage foreclosures, and thrift scandals, many people were rooting Dillinger on.

Devious newspaper reporters, aware that Leach was heading over the edge, couldn't help taunt him by sending notes and letters purportedly from Dillinger, most of which ridiculed the efforts to catch him. Leach would invariably release the letters to the press, completing the circle of manufactured news. One reporter even sent "Kaptain Leach" a book entitled How to Be a Detective. Leach went to his grave thinking it came from Dillinger. (118-19)

When John and the girls, who were always eager to go out, planned a big day at the World's Fair in early November, Harry took a pass. The happy, souvenir laden trio didn't return until late in the evening. "Our pictures are in every newspaper and you're out gallivanting around the fair!" Harry raged. "You're gonna get us all sent back to prison!"

Dillinger, who had learned to let Harry's rantings roll off his back, merely flashed his crooked grin and said, "Well, you gotta take chances now and then." It was an exasperating response from Pierpont's perspective, considering that his bipolar partner hid in the bathroom whenever delivery boys showed up with groceries. (121)

That summer, Cummings also announced that the intense and determined head of the Bureau of Investigation, J. Edgar Hoover, would be staying on for another term. At the time, the Bureau of Investigation worked cases for the Justice Department, mostly policing the White Slavery Act, the Mann Act (taking females across state borders for immoral purposes), the Dyer Act (stolen cars across state lines), and Native American Reservations. Hoover, however, unlike his presidents, felt that was only the beginning of what his troops could do. He envisioned a Metropolis-like army of nameless and faceless agents that gathered information for Washington and operated completely in the dark, prohibited by directive from ever speaking to the press. In 1933, Hoover had a force of 266 such clandestine special agents, along with 60 accountants. His men, in keeping with their underground profile, had no right to carry firearms or make arrests. (123)

Walking back to the vault, Dillinger accidentally stepped on the finger of teller Harold Anderson. "I didn't even say ouch," Anderson recalled. "We all used to talk about what we'd do in case of a holdup ... but when the chips were down none of us did anything ... When you look down the barrel end of a .45 it looks like a cannon!" (136)

Harold Graham, the man Makley shot in a panic, wasn't privy to a similar media bonanza. He was off being treated at the local hospital. "You don't feel the darn thing for the first few minutes. But I was sure feeling it by the time those ambulance boys came." Shot in the wrist and side, he would recover.

After the bandits left, the clerk Don Steel ran and bought a three dollar pint of illegal whiskey, which he and his fellow coworkers quickly polished off. At closing time, they went out for more drinks and oysters before returning to their respective homes. Steel recalls being strangely calm that evening, thanks, no doubt, to the booze. "I didn't begin to feel the effects until two or three days after the holdup. Then I trembled so I could hardly stand up." (143)

With the unemployment ranks sky-high for both legitimate and illegitimate activities, fears that The Terror Gang was planning a militarylike recruitment assault against a prison began to fade. It was a buyer's market for manpower. That was good news for Dillinger and Pierpont because attrition continued to eat away at the ol' gang of theirs, whittling down their nicknames from The Terrible Ten to The Notorious Nine to The Savage Seven to The Furious Five with each new killing or arrest. (147)

The Chicago police, a commanding, six-thousand-member department, once again spoke openly about executing Dillinger and his gang on sight. "We hope, although their trails are cold, to be able to drive them out of town—or bury them. We'd prefer the latter," announced Capt. John Stege, using language that wouldn't be tolerated today. To back up his threat, he organized a handpicked squad of marksmen, put them on the critical night shift, and assigned the deadly crew to Sgt. Frank Reynolds, an accomplished assassin who had already killed twelve crooks at that point in his career. (149)

Briefed in Washington, J. Edgar Hoover jumped in and named Dillinger "The Number One Criminal At Large" a precursor to the FBI's famous "Ten Most Wanted List." Chicago dusted off their Al Capone dictionaries and followed Indiana in naming Dillinger "Public Enemy Number One."

Oddly enough, his status was all due to guilt by association. Dillinger, who had yet to kill anyone, was in no way responsible for Hamilton's behavior. Regardless, it was his picture on the front of the nation's newspapers the following day, and his name on the tongues of Hoover and the Illinois police. (149)

One of the women in the car, Frances Colin, twenty-eight, wasn't so accepting. "They ought to hang that copper for killing another policeman," she said. "But he's a copper, that makes a difference." (150)

Lamenting his own fate, Shouse said, "I wish the cops had put a bullet right in the middle of my forehead. The others, too, would rather die than be returned to Michigan City. You might as well be dead as be there!"

On December 21, a Chicago police goon squad headed by Captain Stege and Sergeant Reynolds took Ed Shouse's words to heart. They burst in on three Jewish felons holed up at 1428 Farwell Avenue and shot them all dead. No officers were injured, and it was questionable whether the robbers and suspected cop killers, falsely rumored to be part of Dillinger's gang, even had time to reach for their weapons—if they had any. Armed or not, Louis Katzewitz, Charles Tattlebaum, and Sam Ginsberg were all spared Shouse's gloomy fate, and Sergeant Reynolds added three more notches to the butt of his .38 Special.

District Attorney Tom Courtney, far from investigating the bloody incident, told reporters that the shooting proved that the Chicago police "do not lack courage and bravery." (151)

When Bernice came to, she was being loaded into an ambulance. She regained her senses enough to fret over the gun-packed suit cases, and the $4,000 stuffed in her shoes. Staying cool, Clark, posing as a tourist complete with a slouch-hat and pipe, accompanied the police back to Evansville. There, he piled his cash and machine-gun-laden suitcases in the police station's lobby. Accepting all responsibility for the accident, he paid the trucker up front to settle the damages, and was subsequently viewed as an all-around great guy. It was an Academy Award-worthy performance, considering that in 1926, Clark had been busted in Evansville for a holdup, and was hunted down by many of the same cops buzzing around the station at that moment.

Clark took a cab to the hospital and discovered that his feisty wife and sister-in-law had successfully fought off all attempts to remove Bernice's shoes while being treated. Taking one for the gang, Bernice also refused ether and endured the pain of having her head stitched up sans painkillers for fear of jabbering under the effect of the drug. (153)

It wasn't happy days for Art McGinnis, either. His cover blown by inept police before he could reap the expected financial bonanza, he no longer had any value and was being callously abandoned by both the Illinois and Indiana law enforcement communities. The one-time vital mole inside The Terror Gang was now being cast off as "a nuisance" and a "waste of time and money." To complicate matters, he had a Savage Seven bounty on his head to boot. Such is the woeful life of a snitch. (160)

While waiting outside, Billie's puppy slipped its collar and ran loose on the front lawn. Dillinger came out and started chasing it. A police officer saw him and lent a hand. For five minutes, Public Enemy Number One and one of St. Louis's Finest teamed up to catch a lady's puppy. (170)

"That's one time your rabbit's foot didn't work, boy," one of the officers quipped.

"That rabbit was a lot luckier than I was," Dillinger responded with a grin, taking it all in stride. (174)

The puppy gave the [Tucson] officers great pause. It was wearing a weird pair of doggie goggles that a fast-talking salesman had pawned on Dillinger, saying the animal needed them to protect its eyes from the desert sand. The cops, fearing it was some kind of gas mask, were momentarily braced for a sudden chemical attack. (175)

Incredibly, in a matter of hours, the "hick town" Tucson police had captured John Dillinger and his entire inner circle, seized their weapons, and confiscated $27,000 of their stolen money. It was the kind of devastating coup d'etat that eluded the embarrassed law enforcement armies of Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, and J. Edgar Hoover's G-Men. To pile on the humiliation, the Tucson cops had done it without firing a single shot. (175)

That afternoon, the giddy Tucson police swarmed the Makley house with guns drawn after neighbors reported that another man had rolled in. The visitor turned out to be a crafty real-estate agent. He figured the gangsters wouldn't be using the places they'd paid for, and was already renting them as "historical sites" for a larcenous profit. The couple who snatched the Dillinger residence was allowed to enjoy the freshly bought food as well.

The local Hudson dealer, with no new 1934s to hawk, somehow got hold of Dillinger's vehicle and immediately put it on display under a ten-foot banner that proclaimed DILLINGER CHOOSES THE 1934 HUDSON FOR HIS PERSONAL USE. Dillinger was not paid for his ringing endorsement. (177)

The two salesmen who ratted out their Tucson drinking buddies filed a claim for what they estimated would be $30,000 in rewards. Not so fast. The True Detective firefighter staked his claim, as did many of the arresting officers. Greed was quickly tarnishing Tucson's heroic image. (178)

Dillinger ended the interview sessions by asking the assembled reporters to urge their readers to "vote for Sheriff John Belton in the next election." The reason for the endorsement was no doubt to polish the apple that controlled his immediate fate. The flattery worked. Belton beamed when he heard about it and dropped his tough guy act a notch.

In the "penthouse," Billie was allowed to entertain the press hounds as well, fawning over her "dashing Romeo" who she described as "gentle as a lamb." Even the officers noted that he held her hand and cuddled her in the car as they were brought in to be arrested, assuring her that they'd been in tougher jams and would survive to make love again. "Isn't he grand?" Billie sighed. "He's always that way, rain or shine. You can't help but love a man like that." (179)

Pierpont, infuriated by the zoo act, put on his usual show, chilling and thrilling the crowd with his obscene tantrums. Dillinger mostly ignored the onlookers, then flipped when he spotted a spectator he was certain was from Indiana. "I can tell you damned Hoosiers," he snapped. "Those other people stop and look, but you just stand and gape!" (182)

'They're putting you on the spot, Johnnie," Pierpont called out. "You're not going back to Indiana!" Kicking and struggling the whole way, Dillinger was dragged down a back stairway to a waiting car and whisked to the Tucson airport. There, with only the clothes on his back—slacks, white dress shirt, and a vest—he was stuffed inside a Bellanca Skyrocket, a high-winged private monoplane owned and piloted by "Smiling" Dale Myers. The battered outlaw was forced to squat at the feet of East Chicago Police Chief Nick Makar and Lake County Chief Deputy Sheriff Carroll Holley. Handcuffed to the frame of the pilot's seat, the Jackrabbit spat, "Hell, I don't jump out of these things." (184)

The Tucson officers were foaming because Captain Leach pulled off the coup by offering nothing more than $300 in rewards. The cops were expecting about $2,500 each from Wisconsin, and rumors swirled that the gang itself was going to funnel another $60,000 worth of stolen bonds to Tucson and Wisconsin officials—washed spic-and-span through their attorney. Seeing it all fall through his fingers, little Chet Sherman grabbed Leach by the collar and shouted "You're everything Pierpont said you were! A double-crossing rat."

Leach offered no reply. At 10:55 P.M., the Golden State limited chugged its way out of the terminal. (185)

Because of the huge crowds of media and gawkers, along with the competing law enforcement agents, Stege wasn't able to execute Dillinger on the runway, as he so ached to do. He would also find it impossible to pullover to the side of the road enroute and blow the bandit away during a manufactured escape attempt. Dillinger, fully cognizant of these factors, was thankful the otherwise annoying press hounds were around—even if it meant surviving to face a murder rap. (188)

"We've got to be going," Dillinger said, almost as a good-bye. Then he looked toward the day room. "We're wasting too much time. Any of you want to come along?" Dillinger's cellmates Fred Beaver and Leslie Carron, both charged with grand larceny, immediately jumped forward. James Posey, a robber in an adjoining cell, asked to go as well. Dillinger ordered Blunk to set them free.

Once his new gang had been recruited, Dillinger pulled the pistol from his pocket and raked it across the bars in front of Warden Baker. Instead of the expected clang of metal on metal, there was only a dull thud. "This is what I did it with," the outlaw said with a huge grin as he displayed the half-finished, wooden pistol. "I carved it out myself. If you don't believe me, come here and frisk me." (201)

As they worked, Dillinger further enlightened the men regarding his original weapon. He had used a razor blade to whittle it from the top rail of a washboard. The barrel was the handle of a safety razor. The wood was blackened with shoe polish. The crafty outlaw was quite pleased with himself. . . .

The chains did the trick and the quartet was back on the road, heading for Peotone. "I suppose you'll be going to Lima to bust your men out of jail?" Blunk asked.

"They'd do as much for me," Dillinger replied.

As they passed a landmark known as Lilley Corners, Dillinger looked up and noted that telephone poles no longer lined the road. He told Blunk and Saager to exit the vehicle. "I'd probably get a better start if I shut you two up right here," he threatened, giving them a moment of terror. "But I never killed nobody, especially that cop, O'Malley, and I don't wanna start now. You guys do whatever you have to do, but I can tell you that's the last jail I'll ever be in."

With that, he fished in his pocket and handed them each four dollars—money he'd lifted from the warden and guards at the jail. "This'll get you to a town. It's not much but it's all I can spare." Blunk declined, but Saager grabbed his share. Dillinger shook their hands and grinned. "Maybe I can remember you at Christmas time?" He climbed behind the wheel of the Ford, told Youngblood to lie on the back floorboard, and sped over a rise toward the south. (209-10)

Locally, Prosecutor Robert Estill's chance of redeeming himself for the embarrassing photo was instantly dashed, his political career in smoking ruins. Sheriff Lillian Holley found herself being pilloried in an unapologetically sexist manner. A quickly produced film documentary claimed she was in the kitchen baking pies when the escape occurred. It was a lie, but the truth that she was sleeping, or dressing for work as she claimed, wasn't exactly vindicating. Her city was being referred to nationally as "Clown Point" even though it was the county facility, and not the city jail, that had been breached. Rival politicians suggested that Holley's Democratic party should dispense with the donkey and use a wooden pistol as their new symbol.

Hard-line conservatives called for her immediate ouster in order to hire a real—that is, male—sheriff. A letter sent to a local resident addressed to "Wooden Gun, Indiana" was delivered without delay. In Indianapolis, wooden guns were passed out at a Republican fund-raising dinner, while speakers spoke of "wooden-headed" Democrats in the state.

Mrs. Holley, like others in the Dillinger saga, stopped speaking of the incident after a few weeks and would never mention it again the rest of her life. That was saying something, considering that she lived to age 103, passing away in 1994. (210-11)

Not everyone shared such vengeful emotions. Dillinger, still viewed as a man of people, was being lauded in letter-to-the-editor sections of newspapers nationwide. Concerned citizens begged the governors of Indiana and Illinois to give him a pardon and leave him alone. Others elevated his importance to society over that of those trying to catch him. A Martinsville farmer, acknowledging the inevitability of another robbery, summed up the feelings best: "As tough as times are, John's doing the country a favor by getting the money out of the banks and back into circulation." (215)

Patrolman James Buchanan popped out of the trees a few moments later. Armed with a sawed-off shotgun, he took cover behind a small boulder placed there as a memorial to the Grand Army of the Republic veterans organization. As with Chief Patton, Buchanan couldn't fire for fear of hitting bystanders. Dillinger didn't harbor such fears. Still using his left hand, he disrespectfully smacked a .45 bullet off of Buchanan's historic rock, sending the chips flying. "Come out from behind there, you son of a bitch!" Dillinger challenged.

Buchanan didn't take the bait. "There isn't any question that bird was an artist with a pistol," he'd later remark. (229)

In Indianapolis, Billie first tried to find Hubert Dillinger at his gas station. When he failed to appear, she went to Maywood and gave Audrey $200 and the wooden gun her famous brother used to escape Crown Point. Dillinger was considerate enough to add a letter of authentication:

. . . Don't worry about me, honey, for that won't help any, and besides, I am having a lot of fun. I am sending Emmett my wooden gun and I want him to always keep it. I see that deputy Blunk says that I had a real forty-five. That's just a lot of hooey to cover up because they don't like to admit that I locked eight deputies and a dozen trustees up with my wooden gun before I got my hands on the two machine guns. And you should have seen their faces! Ha! Ha! Ha! Pulling that off was worth ten years of my life. . .

Don't part with my wooden gun for any price for when you feel blue all you will have to do is look at the gun and laugh your blues away. Ha! Ha. I will be around to see all of you when the roads are better. (233-4)

At Dillinger's old haunt in Crown Point, things continued to look bleak for Ernest Blunk and Sam Cahoon. Both were indicted for complicity in the wooden-gun escape. Virtually everyone else involved, including volunteers and hired vigilantes, were severely chastised. Judge Murray, also blasted in the report, turned around and filed contempt charges against his own grand jurors. Mortified, the six citizens apologized and essentially took back their criticisms of him. A victorious Murray dropped the contempt charges and ended their brief terms. (235-6)

Assistant Attorney General Joseph Keenan, speaking for Hoover's tight-lipped G-Men, announced that the mobilization was part of the Feds' new "War on Crime," instituted a few months earlier. (246)

The Sunday-night, extended-family dinner featured fried chicken and coconut pie, one of John's favorites. John Sr. noted that his son was "carefree and laughing" and seemed to be the boy he was before all the trouble. "I couldn't figure it out for a while. Then I understood. In those old days, when he was a kid, he didn't have any worries on his mind. When he came out of prison, he had plenty. Bitterness, a desire to get even and restlessness. Well, now he'd seen a lot of the country, and " he'd got even, and he sensed he was going to die." (250)

The G-Men, enacting Hoover's new "molls-and-all" policy, swept in, some running right by chauffeur Dillinger in their eagerness to arrest small-fry Billie and Streng. Asked how she'd arrived at the bar, Billie shrewdly said she took a cab.

John eased away, then circled the block, clutching his Thompson and waiting for an opportunity to intervene. As more cops poured in, he concluded it was hopeless. He remained close enough to see his beloved Billie shoved into a DI vehicle, a sight that made him unashamedly "cry like a baby."

At the DI field office in the Banker's Building, the agents gave Billie the bare-light treatment, coming at her in waves, denying her sleep, trying to get her to break down and rat her lover. "They kept me up, talking to me until I didn't know what I was saying. Then they'd leave me alone for a long time. I was nearly crazy. They thought John was coming to rescue me."

Despite her fried brain, Billie kept her forked tongue going, misleading the Feds at every turn. She went so far as to claim that the blood on the snow in St. Paul was from her "monthly sickness," and not her boyfriend's leg as the eagle-eyed neighborhood youth insisted.

No matter how much pressure and physical force they applied, Billie stood by her man. Even when G-Man Harold Reinecke smacked her across the face, the tough Native American beauty didn't buckle—in part because there was nothing to sing. Her Johnnie was living out of the Ford and could have been anywhere. Cleverly vengeful, Billie repaid the violent Agent Reinecke by faking a tearful confession that she was to meet John near their old apartment on Addison at a specific time. G-Men and cops flooded into the area, all to no avail. Billie coyly told the fuming agents that they must have been too clumsy and obvious. (252-3)

John Sr. supported the amnesty idea, telling an exasperated Feeney that he thought his wayward son would make a good law enforcement officer. Others suggested that John Jr. run for governor and then pardon himself. Many felt he could actually win such an election on name recognition alone.

The outlaw certainly had that. Dillinger mania continued to rage across the land. A popular lottery based upon his predicted capture date was shut down, without apparent legal authority, by humorless Indianapolis police. In Duluth, Minnesota, an enterprising street vendor offered envelopes purporting to contain "photos of Dillinger." Eager buyers who paid the half-dollar price found that they had purchased nothing but air. "So, he got away from you, too," the vendor chuckled. A billboard was erected in Loretto, Pennsylvania, welcoming the outlaw to drop by and dine at Lee Hoffman's restaurant. (259)

The nation's most famous criminal defense attorney, Clarence Darrow of the Scopes Monkey Trial fame, sent the outlaw a clear "call me" message through the media when he stated that Dillinger's original jail sentence had been far too harsh. He also chastised the police and government for their tough talk about gunning the robber down at first opportunity. (260)

In Brookville, Indiana, Dillinger look-alike Ralph Alsman, twenty-five, was arrested for the seventeenth time at the end of April. Alsman lived in mortal fear that a cop would eventually shoot him on sight as, they'd threatened to do with the outlaw he unfortunately resembled. (260)

Hoover's men also put a tap on the phone of Terror Gang defense attorney Jessie Levy, an act that would be considered outrageous today.

Expanding their aiding and abetting threats beyond mere relatives, Hoover instructed his field offices to announce that the G-Men would pounce upon anyone who assisted the outlaws in any manner "regard less of the duress to which they might be submitted by the convicts." It would be a hard law to comply with considering the hardware such desperados carried.

The information-crazy Feds began developing their controversial file system on people's personal habits and peccadilloes that would one day be viewed as civil-rights abuses. A notation in Hubert Dillinger's "jacket" is a prime example: "Associates with various girls of loose character, neglecting his wife to do so." Fred Hancock was given the same damning brand in his "permanent record." The agents wasted no time in turning the snitch tables and threatening to rat little Mary Kinder as well, noting that she "has been living a considerable portion of the time with one Carl Walz at Indianapolis." (261)

After a long, chatty breakfast on Saturday, April 21, Emil boldly asked Dillinger to join him in his office. "Emil, what's wrong. What do you want?" Dillinger asked, sensing something was up.

"You're John Dillinger."

"You're not afraid, are you?" the outlaw calmly responded.

"No. But everything I have to my name, including my family, is right here, and every policeman in America is looking for you. If I can help it, there isn't going to be no shooting match."

John smiled and patted the innkeeper on the shoulder. "All we want is to eat and rest for a few days. We'll pay you well and get out. There won't be any trouble." (264-5)

At Rest Lake, the fleeing bandits burst in on the owner, seventy-year old Edward J. Mitchell, and his bedridden wife. "Now, Mother, I'm John Dillinger, but I'm not so bad as they make me out," the Jackrabbit assured the flu-stricken Mrs. Mitchell, placing a blanket around her. "The police are after us and we need a car. We won't hurt you."

The soothing words put the Mitchells at ease. "For an outlaw, that Dillinger was a gentleman," Edward Mitchell would recall: "He made the others behave. No foul language and cool as a cucumber." (277)

"Stop shooting. We're coming out," a female voice cried. The posse's big catch emerged—Helen Nelson, Jean Delaney, Marie Conforti, and Marie's puppy. The abandoned ladies were arrested under assumed names and taken to Eagle River. Still determined to smoke out the big fish, the agents spent the rest of the morning gassing the Little Bohemia Lodge, then riddling it with bullets, all to no avail. Emil and Nan Wanatka watched in horror, kicking themselves for their decision to bring in the Feds. Had they simply let Dillinger leave and pretended not to know who be was, lives would have been saved and their lodge wouldn't have been nearly destroyed.

Once inside and in control, the G-Men scooped up the usual assortment of guns, clothing, and cars. Purvis took Carroll's Buick coupe, borrowed from Louis Chernocky, to use as his own. Dillinger's black Ford was shipped to St. Paul. (278)

None of the arrests, of course, made up for the utter fiasco that had occurred at Little Bohemia. Three civilians shot, one killed, one DI agent dead, a local constable in critical condition—and not a single male gang member caught. The DI was blistered like never before. "U.S. Agents in Dillinger Hunt Called Stupid" the Chicago Herald and Examiner bluntly blared. The Chicago Tribune reported that Hoover's head was about to roll unless he captured Dillinger "real soon." In D.C., various senators and congressmen weighed in with scathing reviews of the federal cops who had once again made Dillinger appear invincible. The usual investigations were launched.

Will Rogers summed it up thusly: "Well, they had Dillinger surrounded and was all ready to shoot him when he come out, but another bunch of folks come out ahead, so they just shot them instead. Dillinger is going to accidentally get with some innocent bystanders some time, then he will get shot!"

The ridicule was such that it even rained down from faraway Germany. Pro-Hitler editors at Berlin's Zwoelf Uhr Blatt threw Dillinger in the face of their regime's overseas critics, accusing America of coddling "murderers and the congenitally inferior," and suggested that the infamous felon be sterilized to prevent him from propagating. (279)

The DI was subjected to further scorn when it was revealed that Washington, D.C. bean counters recommended that the money offered to repair the assaulted Little Bohemia Lodge "not exceed $30." Poetic justice to Nan Wanatka aside, it was yet another public relations disaster that ran counter to the agency's efforts to encourage, or force, the public to cooperate in the capture of Dillinger. (279-80)

After the injured Hamilton eased in, Dillinger ordered the Francises back inside as well. "Don't worry about the kid," Dillinger assured Sybil, who recognized him instantly. "We like kids." (281)

The ink from the Little Bohemia headlines was barely dry when Dillinger's second St. Paul escape hit the wires. Still pounding on the Feds, The Associated Press took pains to point out that the Dillinger hunt had cost the government nearly $2 million and counting, which they said was four times as much as the bank robber had stolen. The amnesty idea might not have been so crazy after all. (282)

Ravaged with gangrene and stinking up the place, Hamilton finally gave up the fight on Thursday, April 26.

Dillinger and some of the Barker-Karpis crew buried their digit-challenged friend in a gravel pit near Oswego, Illinois, covering the body with ten cans of watered-down lye to hamper identification. "Sorry, old friend, to have to do this," Dillinger eulogized. "I know you'd do as much for me." Davis placed a nearby roll of rusty wire over the makeshift grave as a marker. (283)

Despite the excessive shooting, nobody was killed. Chief Culp, hit the hardest, nonetheless recovered. Daub, a large, athletic man who escaped physical injury, never recovered his nerves. Shaken and afraid from that point on, he died within the year. (286)

That same Saturday, Billie Frechette's trial began in St. Paul. Curiously, her case was bunched with those of Dr. Clayton May. Nurse Salt, and moll-turned-snitch Bessie Green. During the noon recess, Billie filtered in with the spectators and walked out of the courtroom. An alert cop intercepted her in the hallway a few feet from freedom. "I was just going to have lunch with the other folks," she cooed. "I was coming back. Really." (287)

The convictions were bumped off the front pages of the newspapers by a far more dramatic event that occurred near Gibsland, Louisiana. Grim-faced Texas lawmen set a trap, then gunned down Clyde Barrow, 25, and Bonnie Parker, 23, the star-crossed lovers who would one day ignite the Hollywood careers of Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway. (288)

Texas Ranger Frank Hamer was campaigning to do his very best as well. Flush with blood fever after helping slaughter Bonnie and Clyde, Hamer offered to do the same to the Jackrabbit. "The government men may not give me a chance to kill him," he lamented. "There's a lot of jealousy in this man-hunting game." (292)

Arthur "Fish" Johnson, always with his ear to the ground, got wind of the plan and appeared at Rohlwing Road on June 22—Dillinger's thirty-first birthday—hawking bulletproof vests he'd acquired from Al Capone's soldiers. Baby Face Nelson bought a pair for a hefty $300 each. Nelson might have been wise to immediately put one on. He and VanMeter nearly went at it when Baby Face began to rant that Mazie was cooperating with the Feds. "That guinea bitch is no good and you'd better pop a cap on her," Nelson demanded. Chase and Negri moved away, expecting the bullets to fly any second. Instead, Nelson convinced the paranoid VanMeter that he was telling the truth, naming the agent she was seen with. While it was no secret that the Feds were squeezing the girls, the mystery was in determining who, if any, was. playing along. (303-4)

Audrey Dillinger did her part to remember her brother on his big day, purchasing a classified ad in the Indianapolis Star. "Birthday greetings to my darling brother, John Dillinger, on his 31st birthday. Wherever he may be, I hope he reads this." As she expected, other newspapers yanked the notice from the bowels of the tiny want ads and splashed it on their front pages, assuring that John Jr. saw it. (305)

Bruce Bouchard, the manager of an area radio distribution company, felt a sharp pain in his side as he hit the floor. Clutching his waist, he was shocked to discover that he was bleeding. An errant slug from Dillinger's deadly noisemaker had ricocheted off the ceiling and nailed, Bouchard in the hip. The outlaw glanced at the fallen executive and shrugged, as if to apologize for the freak accident.

Behind the tellers, Merchant Bank Vice President C. W. Coen disappeared under his desk. He would remain there through the entire incident. His son and coworker; Delos Coen, was standing at his post talking with bank director Perry Stahly when the bullets started flying. Unlike his dad, the younger Coen stood paralyzed in place, mouth agape. He couldn't help but stare directly into the mischievous eyes of the famous bandit. Dillinger, flying on the thrill of it all, lowered his machine gun and gave Coen an unforgettable grin. (310)

VanMeter bunched the shoe store hostages together and took cover, stationing himself directly behind Chebowski. He fired his unique rifle over her shoulder, splitting her eardrums with every retort. Despite the pain, the terrified Chebowski covered her eyes instead of her ringing ears, choosing at that moment to see no evil rather than trying not to hear it. (313-14)

Harry Berg, the jeweler who plugged Baby Face Nelson, didn't waste time getting back to business. While the gang was still racing across the countryside, he had already posted a sign in his shop window stating NOT HURT. OPEN FOR BUSINESS. (322-3)

In Ohio, Pierpont and crew were allowed to address the media following their stay of execution. "Newspapers put us here," Pierpont spat. "We didn't do the Lima job. Indiana authorities, from the state house down, know who did that job, but they built up the case against us because we were hot. If Johnny Dillinger is raising a $20,000 fund to come to our defense, tell him, if you can, to send us a couple of fins for cigarettes. We owe Dillinger nothing ... He owes us even less ... We both hope he's never caught ... He's one of the grandest fellows that ever lived. . . . No, of course, we don't know where he is."

Asked about rumors they were going to kidnap the daughter of Ohio's governor, Makley snapped, "Hell, we didn't even know he had a daughter 'til we read it in the papers." (330)

Neither Chef Steve nor his attentive waitress-wife Millie, an immigrant from Yugoslavia, were aware that their "spiffy" dressed, big-tipping late-night diner was the infamous John Dillinger. They knew Anna was a madam, but her escort was just another wealthy "John" from their perspective.

Dillinger even tested their knowledge one evening as Steven was counting the day's take. "That's a big wad of money, Steve," Dillinger said with a devilish grin. "Aren't you afraid John Dillinger might drop in and take it away from you?"

"No, he just robs from the crooked banks," Jankovich replied, going with the popular, Robin Hood-like legends that had been created around the notorious bandit. "If Dillinger knew I needed money he'd probably give it to me."

"Yeah, he probably would," a pleased Dillinger said as he exited. (335-6)

Dillinger let his newly dyed hair down at area amusement parks. The man who survived dozens of high-speed chases was not surprisingly a roller-coaster junkie. "We never went on one and then stepped off. Three times on each one was the quota, and sometimes we rode more than that," Polly remembered. "You would have thought he had never grown up. Why, he'd yell like an Indian all the way down, and then he'd lean over and kiss me when we went around the curves. Boy, did we have fun." (337)

The man Sally knew as Jimmy Lawrence was also prone to breaking out in song when he was happy, crooning his favorites "All I Do Is Dream Of You," sung by Gene Raymond in the film Sadie McKee, which he never failed to dedicate to Polly, and "For All We Know," from band leader Hal Kemp (and later covered by Nat King Cole among others). Polly said he was very loving in private, a prized cuddler, but didn't like to display his affections publicly. He was uncomfortable as well when others around him canoodled. During card games, he would fine any couple that hugged or kissed five cents. (337-8)

John Dillinger the outlaw returned to Anna's from the train robbery casing mission on the morning of July 20, transforming back into the mild-mannered Jimmy Lawrence. The next day, Sergeant Zarkovich and his captain, Tim O'Neill, were secretly meeting with their Chicago counterpart Capt. John Stege. Zarkovich and O'Neill picked Stege because they thought he might be receptive to their deadly solution to the "Dillinger problem"—the unnerving possibility that the outlaw might connect the corrupt East Chicago cops with the Lake County underworld. Sergeant Zarkovich was particularly vulnerable to such an accusation. If captured, Dillinger might try to link him to the Crown Point escape, the hit on Zarkovich's rival detectives, various payoffs, and possibly even the long-rumored, banker-approved setup behind, the robbery of First National Bank of East Chicago that cost Sgt. William O'Malley his life. Zarkovich figured Stege's trigger-happy Black Shirts were the perfect group to handle the sticky situation. "We will deliver John Dillinger to you right here in your own city," Zarkovich pitched to the ambitious Captain Stege. "And we can divvy up the rewards. All you have to do is make sure that he isn't taken alive." (338)

Checking to see if anybody was watching, she grabbed the delicatessen phone and literally and figuratively "dropped a nickel," dialing Andover 2330. "He's just come," she whispered her lie to Purvis. "I'm not sure where we're going—either the Marbro or the Biograph." She hung up, purchased the butter, and skittered back upstairs, perspiring profusely.

Purvis fought off a moment of panic. He and Cowley had a detailed a plan for the Marbro, but nothing for the Biograph. It was a glaring oversight considering that a Shirley Temple movie was playing at the Marbro, and a gangster film starring Clark Gable and William Powell was at the Biograph. It didn't take an FBI profiler to determine which show Dillinger would choose. (343)

Zarkovich, O'Neill, and the East Chicago, Indiana, crew traded knowing smiles. Purvis had just given them carte blanche to blow John Dillinger away. (345)

Dillinger enjoyed the movie immensely, laughing, whispering private jokes, and trying to sneak kisses. During one scene, a secretary warned her prosecutor boss, William Powell, against inviting his old friend-turned-crook, Blackie Gallagher, to his wedding. "Remember what happened to the district attorney in Chicago just for having his picture taken with some gangsters having dinner" she reminded. It was an obvious reference to Dillinger's Crown Point photo session, and the true life gangster got a big kick out of it. (349)

Seeing the people starting to leave, Purvis felt his knees knocking together. His mouth was dry as cotton. The future of their upstart federal police agency [the FBI] might very well be determined in the next few minutes. (351)

Above the din, the anguished voices of two women could be heard. Both were screaming that they'd been hit. The first, Etta Natalsky of 2429 Lincoln, was the woman that Dillinger had bumped into. A bullet passed through her fleshy upper left thigh, spurting blood on her dress. The slug may have been the same one that passed through Dillinger's chest. The second injured lady, Theresa Paulus, twenty-nine, of 2920 Commonwealth Avenue, was leaving the movie with her companion, Fred Kuhn, when a wild volley plunked her in the hip. Neither woman was seriously hurt, but their injuries once again defined the recklessness of the jumpy G-Men. (354)

Although five shots had been fired at point-blank range, only a pair hit the mark. Two bullets hit civilians, and the fifth went who knows where. The ultimate successful result would act to diffuse this latest example of reckless law enforcement.

A gleeful Purvis allowed the press hounds in at midnight to photograph the body—something that would never be tolerated today. He also ordered that the bandit's watch be taken out of sight to keep anyone from identifying Polly. This was said to have been done in deference to the fact that she had once been married to a cop. The real reason, no doubt, was to conceal her role in the setup. (357)

At the Ohio State Prison, Pierpont, Makley, and Clark naturally took the news hard. Dillinger had been their only hope to escape their fates. "You got a brother?" Pierpont asked a reporter who queried him for a response. "Then you just write about your own brother and you'll have the right dope on Johnnie Dillinger."

"Yeah," Makley agreed. "He was the kind of guy anyone would be glad to have for a brother." (359)

At the Federal Detention Home in Milan, Michigan, Billie's reaction was mostly internalized. "That's too bad," she said softly, her eyes filling with tears. (359)

The outlaw's brain was removed, ostensibly so doctors, scientists, and physiologists could dissect it in an attempt to determine what made him go wrong. The organ, placed in a jar of formaldehyde, was apparently lost or stolen and has never resurfaced. That, of course, fed "Frankenstein II" tales. (360)

While most Americans viewed the assassination as par for the course, the Germans weren't so understanding. "Is a policeman calling a man by his first name before shooting him down a sufficient trial?" asked the [Nazi-run] Voelkischer Beobachter newspaper. (361)

In Chicago, a street artist used chalk to scribble a poem on a brick alley wall near the Biograph:

Stranger, stop and wish me well

Just say a prayer for my soul in hell

I was a good fellow, most people said

Betrayed by a woman all dressed in red.

Chicago Coroner Frank Walsh, pausing to reflect, stated that, he hoped Dillinger's undignified death served as a warning to young men that he wasn't someone to be idolized. A few hours later in Los Angeles, an armed twenty-one-year-old man was shot to death by the police. "I'm the new Dillinger!" he screamed before the bullets did him in. (362)

A month after Dillinger's death, Homer VanMeter was gunned down Bonnie-and-Clyde-style in a St. Paul alley. The local cops who trapped him there fired more than fifty shots. As with Dillinger, it's suspected that the trigger-happy officers pilfered his body of as much as $10,000. (364)

Edgar Hoover, practically built his agency on John Dillinger's back, using the headline-grabbing, border-crossing bandit to stifle politicians who were vehemently against creating a federal police force. It's no coincidence that the DI/FBI's two most important legislative advances—the ability to carry weapons, and the right to make arrests—occurred during John Dillinger's brief reign.

Using Dillinger as his most effective sledgehammer, Hoover was able to get his boys into the game by pushing for and obtaining, new laws making various crimes national offences. Robbing federally insured banks, racing stolen cars across state lines, and felons hopscotching states after escaping prison were all placed under the jurisdiction of the G-Men. These initial Dillinger-attributed laws triggered a legislative avalanche that would roar down the Washington, D.C., mountain and relentlessly expand the FBI's powers over the subsequent decades.

Considering the above, it's not hard to understand Hoover's nostalgia for keeping Dillinger's death mask outside his office.

It's also possible, as Hoover was no doubt keenly aware, that had things played out a little differently, Dillinger may have prevented the creation of the FBI. If the notorious bandit had kept his sensational act going for another year or so, Hoover might have ended up as a footnote in history. Disasters like Little Bohemia, combined with the G-Men's inability to stop Dillinger, would have empowered Hoover's critics and given them the ammunition needed to defeat his design for a massive federal police force. (368-9)

|