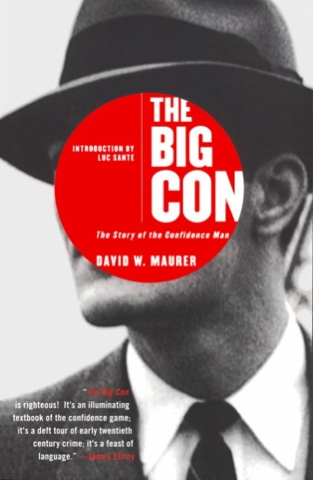

The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man

David W. Maurer (1940; rpt. 1999)

(If you've seen The Sting, you'll recognize that The Big Con was a major source for that film's screenwriter(s).)

He turned the idea over in his mind for some time and finally opened, in a shack of a building, what he called the Dollar Store. In the windows he exhibited all kinds of colorful, useful, and even valuable merchandise—with all items priced at one dollar—and he soon had customers a-plenty. Inside there were several monte games going, replete with shills and "sticks" to keep the play going at a lively pace. Once a gullible customer was lured in by the bargains he saw displayed, Ben "switched" his interest from the sale to the three-card monte, which was being expertly played on barrelheads. The merchandise never changed hands. It remained always the same. But the customers were different, and each one left some cash in Ben Marks' money belt. Like most pioneers Ben did not realize the importance of his innovation. (7)

Other forms of the short-con, largely some form of gambling games, copied the idea, and little Dollar Stores sprang up all over the United States—one of them, incidentally, in Chicago, growing into a great modern department store owing to the fact that the founder, who originally leased the building for a monte store, found that he could unload cheap and flashy merchandise at a dollar and make more money than he could at monte. (8-9)

The roper told the victim that he had been selected for a part in this scheme because he could be depended upon. The roper's problem was this: he has been abused and neglected by his employer, who, he says, is really an old skinflint. He has decided to quit his service—but not without making some money for himself. The next fight, for which he is now making arrangements, will be held in Council Bluffs. He has contracted with his employer's fighter to "take a dive"—pretend to be knocked out—in the tenth round. His employer will bet heavily on his own fighter. He, the secretary, cannot personally bet against his employer; hence he needs someone with money who will bet heavily on the other fighter, then divide the proceeds. It is a sure thing. (12)

The fight was held before a very limited audience, for in those days prize fighting was illegal in most states and prize fights were held clandestinely, like cock fights today, However, for the mark's benefit, the fighters put on quite a show. In the sixth round, something happened which no one had counted on. The millionaire's fighter delivered a terrific right over his opponent's heart and he fell to the ground, spurting blood from his mouth. All was confusion. The millionaire's "doctor" came forward with his stethoscope and pronounced the fighter dead. The mark was dazed; the millionaire collected the bet (which was already in his possession, since he had taken the satchel with the stakes in it) and everyone was in a hurry to get out of town before the local authorities got wind of the fight and arrested them for being accessories to manslaughter. Thus the mark blew himself off and the con men split the amount of his bet. (13)

The wire, the first of the big-con games, was invented just prior to 1900. It was a racing swindle in which the con men convinced the victim that with the connivance of a corrupt Western Union official they could delay the race results long enough for him to place a bet after the race had been run, but before the bookmakers received the results. For this game two fake set-ups were used. The first was a Western Union office, complete with operators, telegraph instruments, clerks and a "manager"; some mobs economized by sneaking in and using real Western Union offices until the company put a stop to it. (16)

The big store, the boost, and all the necessary stage settings are again called into play. When the time comes to make the big bet, the sting is put in a little differently. (49)

Big-time confidence games are in reality only carefully rehearsed plays in which every member of the cast except the mark knows his part perfectly. The insideman is the star of the cast; while the minor participants are competent actors and can learn their lines perfectly, they must look to the inside man for their cues; he must be not only a fine actor, but a playwright extempore as well. And he must be able to retain the confidence of an intelligent man even after that man has been swindled at his hands.

The reader may be able to get a better view of the situation if he will imagine for a moment what would happen if, say, fifteen of his friends decided to play a prank on him. They get together without his knowledge and write the script for a play which will last for an entire week. There are parts for all of them. The victim of the prank is isolated from everyone except the friends who have parts. His every probable reaction has been calculated in advance and the script prepared to meet these reactions. Furthermore, this drama is motivated by some fundamental weakness of the victim-liquor, money, women, or even some harmless personal crotchet. The victim is forced to go along with the play, speaking approximately the lines which are demanded of him; they spring unconsciously to his lips. He has no choice but to go along, because most of the probable objections that he can raise have been charted and logical reactions to them have been provided in the script. Very shortly the victim's feet are quite off the ground. He is living in a play-world which he cannot distinguish from the real world. His natural but latent motives are called forth in perfectly contrived situations; actions which, under other circumstances, he would never perform seem natural and logical. He is living in a fantastic, grotesque world which resembles the real one so closely that he cannot distinguish the difference. He is the victim of a confidence game.

Every reader probably feels sure that he is proof against con games; that his native horse-sense would prevent him from being made a victim, that these tricks which seem so patent in print would never ensnare him. Perhaps so. But let him remember that competent con men find a good deal of diversion in "playing the con" for one another, and that many a professional has suddenly realized that he is the butt of a practical joke in which all the forces of the big con have been brought to bear upon him. (101-2)

People who read of con touches in the newspaper are often wont to remark: "That bird must be stupid to fall for a game like that. Why, anybody should know better than to do what he did. . . ." In other words, there is a widespread feeling among legitimate folk that anyone who is he victim of a confidence game is a numskull.

But it should not be assumed that the victims of confidence games are all blockheads. Very much to the contrary, the higher a mark's intelligence, the quicker he sees through the deal directly to his own advantage. To expect a mark to enter into a con game, take the bait, and then, by sheer reason, analyze the situation and see it as a swindle, is simply asking too much. The mark is thrown into an unreal world which very closely resembles real life; like the spectator regarding the life groups in a museum of natural history, he cannot tell where the real scene merges into the background. Hence, it should be no reflection upon a man's intelligence to be swindled. In fact, highly intelligent marks, even though they may tax the ingenuity of the con men, respond best to the proper type of play. They see through the deal which is presented, analyze it, and strike the lure like a flash; most con men feel that it is sport of a high order to play them successfully to the gaff. It is not intelligence but integrity which determines whether or not a man is a good mark.

Stupid or "lop-eared" marks are often played; they are too dull to see their own advantage, and must be worked up to the point again and again before a ray of light filters through their thick heads. Sometimes they are difficult or impossible to beat. Always they merit the scorn and contempt of the con men. Elderly men are easy to play because age has slowed down their reactions.

Most marks come from the upper strata of society, which, in America, means that they have made, married, or inherited money. Because of this, they acquire status which in time they come to attribute to some inherent superiority, especially as regards matters of sound judgment in finance and investment. Friends and associates, themselves social climbers and sycophants, help to maintain this illusion of superiority. Eventually, the mark comes to regard himself as a person of vision and even of genius. Thus a Babbitt who has cleared half a million in a real-estate development easily forgets the part which luck and chicanery have played in his financial rise; he accepts this mantle of respectability without question; he naively attributes his success to sound business judgment. And any confidence man will testify that a real-estate man is the fattest and juiciest of suckers. (103-4)

And Joe Furey—whose statements must be discounted because of his reputation for tall talk—adds, "At that time [1925-1929] marks were so thick in Florida that you had to kick them out of your way." (116)

The sagacity of Buck Boatwright's philosophy that any man with money is worth playing for would not be questioned by any experienced con man. The first thing a mark needs is money.

But he must also have what grifters term "larceny in his veins"—in other words, he must want something for nothing, or be willing to participate in an unscrupulous deal. If a man with money has this trait, he is all that any con man could wish. He is a mark. "Larceny," or thieves' blood, runs not only in the veins of professional thieves; it would appear that humanity at large has just a dash of it—and sometimes more. And the con man has learned that he can exploit this human trait to his own ends; if he builds it up carefully and expertly, it flares from simple latent dishonesty to an all-consuming lust which drives the victim to secure funds for speculation by any means at his command.

If the mark were completely aware of this character weakness, he would not be so easy to trim. But, like almost everyone else, the mark thinks of himself as an "honest man." He may be hardly aware, or even totally unaware, of this trait which leads to his financial ruin. "My boy," said old John Henry Strosnider sagely, "look carefully at an honest man when he tells the tale himself about his honesty. He makes the best kind of mark. . . ." (116-17)

The mark's honesty is always a standing joke among grifters. (118)

Some con men have observed that marks respond to con games differently according to nationality, with well-to-do American businessmen being the easiest. "Give me an American businessman every time," declared one of the most successful of the present generation of ropers, "preferably an elderly executive. He has been telling other people what to do for so long that he knows he can't be wrong." Perhaps it naturally follows that, if a mark has made money in a speculative business, his acquisitive instincts will lead him naturally into a confidence game; in the light of his past experience and his own philosophy of profit, it is a natural and normal way of increasing his wealth; to him, money is of value primarily for the purpose of making more. (124-5)

But it is difficult for the legitimate citizen (and sometimes for the mark himself) to understand why a man, once trimmed on a con game, will go back for another dose of the same medicine. Yet it happens all the time. Grifters have an endless fund of stories which illustrate this fact.

"I roped a mark for the last turn at faro-bank in Chicago," said a fine short-con man named Scotty. "Old Hugh Brady played for him. The mark went for about ten grand—all he had at the time. About two years later Old Hughey was strolling down Clark Street and he met Mr. Mark, who was tickled to see him again. He said, 'I've been looking for you for a long time. I've raised some more money and I'd like to play that faro game again. Brady told the mark that he had moved to another hotel. He rented another room and framed the gaff and took the mark all over again." (126-7)

If business is good, he keeps an appointment book after the fashion of a doctor or dentist and plays the marks according to a rigid schedule. (135)

The roper and the insideman are the principals of any mob. Upon them depends the success of the big store, for, however elaborate a set-up is provided, and however secure the fix, all is useless without the services of a man who can bring in marks, and one who can give them a convincing play. Each must perform a specialized piece of work and needs certain personal qualifications and experience which fit him for the task. Some men, and rare they are, can handle either end with great success, as, for instance, the Yellow Kid, Frank MacSherry or the Jew Kid. Others, like Limehouse Chappie and Charley Gondorff, have consistently specialized in inside work, at which their talent falls little short of genius, but could not steer a hungry man into a restaurant. (137)

Never ask a mark embarrassing questions. You know how you feel when someone lets the cat out of the bag. Take it easy with any fool, and always lead your ace.

Never boast about your rags, but brag about your long cush. That will lead him along to brag about his long jack, amd then you're getting somewhere, brother. If he is hard-shelled Babbitt, why you're one too. (140-1)

"Never be untidy or drink with a savage. There is nothing worse than drinking when you are trying to tie up a mark. You've got to have your nut about you all the time. You need what little sense you've got to trim him—and if you had any sense at all, you wouldn't be a grifter."

In all seriousness, however, the most important qualification for a roper—so important, in fact, that he would starve without it—is what is known in the underworld as "grift sense." No one, it seems—not even the grifters themselves—can say just what grift sense is. It appears to be a faculty which the grifter is acutely aware of when he needs it; a something that "clicks" within him, telling him when he meets a mark that he can beat, enabling him to sense at once whether or not the man is good for a play and to chart the mark's probable reactions to the game. (141)

In addition to grift sense, a con man must have a good deal of genuine acting ability, He must be able to make anyone like him, confide in him, trust him. He must sense immediately what aspect of his personality will be most appealing to his victim, then assume that pose and hold it consistently. If the mark is a wealthy farmer, he must assume those characteristics which he knows willl rouse the farmer's confidence and friendship, He must be able to talk over the farmer's problems with sympathy and understanding. (143)

After the mark has taken the bait, and while he is making the easy money which prepares him or the final plunge, the roper has complete charge of him; that is, he has him tied up, although the mark firmly believes that he is keeping the roper under control at the confidential suggestion of the insideman. "Put a thief to watch a thief," laughed one con man. "I'll bet some old-timer thought of that." (144-5)

If the insideman handles the blow-off properly, the mark hardly knows that he has been fleeced. No good insideman wants any trouble with a mark. He wants him to lose his money the "easy way" rather than the "hard way" and the secret to long immunity from arrest is a properly staged blow-off, with the mark blaming the roper and feeling that the insideman is the finest man he ever knew. It is the mark who is not cooled out properly or is mishandled by a clumsy or incompetent insideman who immediately beefs; furthermore, if he is sure that he has been swindled and if the local police do not act, he may go higher up, with revenge rather than recovery of his money as his object. Marks of this type can upset the whole corrupt political machine and even land not only the con men but perhaps some of the police and the fixer as well behind bars.

Good insidemen are rare; they do not seem to occur so frequently as good ropers. And there can be only as many first-rate stores as there are first-rate insidemen. Since good ropers like to work only with expert insidemen, the natural result is that the best ropers cluster about the best insidemen, forming a kind of closed corporation, or monopoly, with the control resting in the hands of the insidemen and their fixers. (154)

Willie Loftus always took great pride in his boodle. When the play reached its height, he would have money all over everything, the counter, the shelves, and the floor. Finally, he would call to a clerk, "Hey, George, get this stuff out of my way."

"What shall I do with it?" asks the clerk.

"I don't give a damn what you do with it," Loftus would say, "sweep it out if you have to, but get it out from under my feet." Loftus liked a boodle with quantities of new crisp bills in it. "I like to hear them squeech under foot," he said. This boodle, properly handled, is what really rouses the larceny in the mark and makes him want to get some for himself. When the manager goes to pay the mark off, and stacks pile after pile of bills before him, it makes an impression which no mark ever forgets. (158-9)

Confidence men are not unaware of their social pre-eminence. The underworld is shot through with numerous class lines. It is stratified very much like the upperworld, each social level being bounded by rather rigid lines determined largely by three factors: professional standing, income, and personal integrity. While, as in the upperworld, income has much to do with social position, professional excellence and personal "rightness" appear to play an even greater part among con men than they don the upperworld.

There are rigidly observed class distinctions in the underworld. In a society where one's reputation depends solely upon his individual exploits, and where one is judged by his peers or his superiors, social status is not easily attained. There is no public as a court of last appeal. If, for instance, a country physician is unknown to his confreres, he may find solace in the fact that he is regarded as an important person by the patients he serves. If a writer is panned by the critics and his colleagues, he may still be a hero to his public. But a con man—with the exception of that rare individual who seeks newspaper notoriety—has no public. He is judged by his colleagues alone. And the underworld has a very keen sense of professional values. (169)

When we think of cheese, it's Wisconsin; when we speak of oil, it's Pennsylvania; but with grifters, it's Indiana. Many a first-rate con man has hailed from that state, and many, many more second- and third-raters. . . .

Con men look puzzled and scratch their heads when you ask them why this should be so. A former insideman for the Wonder says, "I don't know why, but the state of Indiana is out in front in turning out grifters of all kinds. At one time you could go to almost any county fair and some farmer would take you aside and show you some new kind of flat-joint [crooked gambling device] that he had invented." Another con man who got his start on the grift playing the short con with circuses adds: "It's an old saying among grifters that any Hoosier farmer would come up to you and ask you where the squeeze [controlling device] was on your joint, and then show you that he had figured out a better one. So I guess the farmer boys thought flat-jointing was better than looking at a horse's tail all day for about a buck." (173)

Representative con men who got their start on the short con include: Post and Allen (the spud and the gold brick), Pretty Duffy (roper for mitt stores), Curley Carter (the lemon), Jimmy the Rooter (flat-jointer), Kid Barnett (three card monte), Swinging Sammy (the hype), the Leatherhead Kid (8 dice player), Sheeny Mike (three-card monte), John Singleton, the Painter Kid, Wildfire John (the tip), Honey Grove Kid (foot-race store), Johnny Taylor (the hype). (175n.)

In addition to those men already mentioned who worked for the mitt stores, the following are representative of those who left the ranks of professional gamblers to join the confidence men: Big Bill Keely (card cheater), Plunk Drucker (the Punk Kid) and Nigger Mike (deep-sea gambler), Queer-pusher Nick (deep-sea gambler and smack player) and Slobbering Bob (mitt player). (176n.1)

Other con men with legitimate backgrounds range from N____ Q____ (engineer and contractor) to the Square Faced Kid (mule-skinner) and from Charley Gondorff (bar-tending) to the Hashhouse Kid (waiter). The Yellow Kid, at the top of the list, was born a con man and never in his life had time for any other occupation. (178)

Thus is begun a cycle which is likely to continue, with minor variations, throughout a lifetime, for most con men gamble heavily with the money for which they work so hard and take such chances to secure. In a word, most of them are suckers for some other branch of the grift. (180)

It is indeed strange that men who know so much about the percentage which operates in favor of the professional gambler will risk their freedom for the highly synthetic thrill of bucking the tiger. Yet a big score is hardly cut up until all the mob are plunging heavily at their favorite game; within a few weeks, or even a few days, a $100,000 touch has gone glimmering and the conmen are living on borrowed money, or are out on the tip or the smack to make expenses. (180)

There is at least one ill-mannered exception to this generalization who deserves a bit of space because he is widely known among con men as the prime example of everything a con man shouldn't do or be. He is the prosperous Red Lager. Ignorant and repulsive-looking, freckled to the point of blotchiness, with the nasty shade of blue eyes which often accompanies a certain cast of red hair, awkward and slew-footed, Red Lager is certainly the acme of unattractiveness among con men. He is everything and does everything which, theoretically, a good con man shouldn't. He has never heard of Dale Carnegie and is unaware of the barest rudiments of the science of "influencing" people; yet he has made a fortune on the pay-off. And he has a son, the exact replica of his father down to the duck-like walk, who, despite his addiction to drugs—one vice which the old man shunned—is today a successful confidence man. (185)

Some of the old-timers took up opium around 1900 when it was considered no more dangerous than smoking cigarettes—when many citizens on the West Coast placidly puffed the pipe on their own front porches. . . . (188)

"My boy," old John Henry Strosnider once said, "the best way to avoid the big house is not to tell your twist how clever you are. Broads have been known to put the finger on smart young apples. So cop my advice, and last longer on the outside than on the inside. . . " (194)

A good grifter never misses a chance to get something for nothing, which is one of the reasons why a good grifter is often also a good mark. Indiana Harry, the Hashhouse Kid, Scotty, and Hoosier Harry were returning to America on the Titanic when it sank. They were all saved. After the rescue, they all not only put in maximum claims for lost baggage, but collected the names of dead passengers for their friends, so that they too could put in claims.

This tendency to want something for nothing extends to all branches of the grift. A tale is told of Johnny Tolbert and a team of pickpockets, one of whom, Kansas City Boze, was killed in a fight in El Paso. Johnny Tolbert, fixer for the city, went with the surviving partner to an undertaker's establishment to arrange for laying Boze away. While Johnny stalled the undertaker, Boze's partner changed the tag from a $500 casket to a $1,000 one, and placed the $1,000 tag on a cheaper casket. Johnny then bought the $1,000 job for $500 and paid for it in cash. As they left the funeral home, Boze's partner turned to Tolbert and said, "You know, Boze would like that." (200-1)

Nothing pleases him more than to tish a lady—that is, to place a fifty-dollar bill in her stocking with the solemn assurance that if she takes it out before morning, it will turn into tissue paper. Being a woman, she removes it at the earliest opportunity, only to find that it has turned to tissue paper, often with a bit of ribald verse inscribed upon it. (203)

When con men go to prison, they naturally exploit their position as fully as they can. They are model prisoners but before they have been there a day they are "shooting the curves" (conniving for privileges). They live off the fat of the land, enjoy a diet of their own choosing, and sometimes manage a business of some sort which makes them a very good profit. One con man of my acquaintance, at the end of a year in a northern prison, had managed to gain control of the commissary and was actually selling and reselling foodstuffs to the state which had imprisoned him. (207)

"What becomes of con men?" l once asked an old-timer.

"They just dry up and blow away," he answered laconically.

But they don't. Whatever happens to them during the course of their lives, it is a notable fact that, as their years increase, they remain young in spirit. They do not become "dated" as many men do who are marked indelibly with the characteristics of a particular generation. In attitudes, in dress and manners, in tastes and language, they live always, like theatrical folk, in the present. Their interests do not lag. They do not live in the past; perhaps they prefer not to do so. (208)

Old John Henry Strosnider said, "I think the reason that a con man never dies is that, like the Wandering Jew, he is always on the go. He is always traveling somewhere and seeing and doing new things. If he is in California, he looks forward to going to Florida, from there to Cuba, and so on. Then, too, he is always with young people., He dresses and acts like a young man, even when he is seventy. His talk and manners are up to date. I never saw an old pappy con man. Besides, con men never loaf around much. They are always active rooting out a mark. Much of their time is spent in the open air. Nowadays you will find the old-timers on any golf links where they can get by." (209)

The public is not only apathetic but naive toward the relationship between confidence men and the law. The man in the street sees crime something like this: if a confidence man trims someone, he should be indicted and punished; first he must be caught; then he must be tried; then, if convicted, he should be sent to prison to serve his full term. The average citizen—if we ignore his tendency to wax sentimental about all criminals—can be generally counted upon to adopt the following assumptions: that the victim of the swindle is both honest and unfortunate; that the officers of the law want to catch the con men; that the court wishes to convict the criminals; that if the court frees the con men, they are ipso facto innocent; that if they are convicted, they will be put in the penitentiary where they belong to serve out their time at hard labor. If these assumptions even approximated fact, confidence men would have long ago found it impossible to operate. (214-15)

Con men are very careful to pay off the fixer and to protect him from publicity on all occasions; in return, the fixer serves the con men faithfully and well. It is significant that American criminals do not, as a rule, fear the law; they fear the fixer, whose displeasure can follow them anywhere and whose word can put them behind bars more effectively than any local enforcement agency. (217-18)

If a city provides complete and exclusive protection for one or more favored con mobs, it is known as "airtight." This means that the fix is very strong, that the con men are quite secure, and that all competition will be discouraged by vigorous non-fixable prosecution. (224)

On a police force there are two kinds of officers "right" and "wrong." A right copper is susceptible to the fix, whether it comes from above, or directly from a criminal. A right copper really has larceny in his blood and, in many respects, is an underworld character, a kind of racketeer who takes profits from crime because he has the authority of the law to back up his demands. He differs from the professional criminal only in that he aligns himself with legitimate society, then uses his position to protect the thief and to betray the legitimate citizen. A con man is what he is; he is at least sincere and straightforward in his dishonesty. However, the con men do not hate or despise a right copper; they simply regard him as wise enough to take his share of the profits, knowing full well that if he doesn't, some other copper will. So, in a sense, the con man looks upon the right copper as a businessman who is smart enough to sell his wares at a price which the criminal can afford. (224-5)

Con men universally agree that the bum raps always come from right coppers and not from wrong ones. In other words, the maxim of the big con works both ways—if you can't cheat an honest man, neither will an honest man cheat you. (225)

In the city where the store is located, the police officers and detectives have little to do to collect their "end." If the mark can be cooled out properly by the insideman, they may never be called upon. If the mark beefs and goes to the police, he is treated very well, asked to tell his story, gives a description of the con men, and may even be asked to look through a rogues' gallery (from which the local boys' portraits have been carefully removed) in the hope that he can identify his malefactors. In other words, the police and detectives make a rather elaborate show of going through the same process they would use if they were really trying to catch someone. (225-6)

Let us look a little further into the relationship between the con man and the minions of the law.

The assistance rendered the con men by the fixer is just what the con men pay for, no more, no less. They pay for the protection of the police, and they are entitled to it. But what about the con men who are not paying protection locally? The right coppers habitually look upon all grifters as a source of revenue; a con man who is not paying, even though he is not working in that city, represents undeveloped opportunity. And so the right coppers proceed to develop it. Once a con man is recognized, he is picked up on the street and shaken down. He pays to remain free, even though there may be no immediate order for his apprehension. This is known as "stem-court," the implication being that the con man is arrested, tried, convicted and fined, all on the "stem" or street. "All big cities have coppers on the grift out looking for con men," said one professional. "The con men know whether they are right or wrong." This fact is emphasized by every con man who comments on the fix.

The reaction of con men toward this type of shakedown is philosophical. They believe that, if one doesn't have sense enough to avoid right coppers, he gets only what he deserves. Furthermore, he may need the services of that officer sometime, so he usually decides that it is better to pay. (227-8)

Gone, alas, are those hurly-burly days before the teletype and the squad car, when the boys played cops and robbers for all they were worth. (230)

However, it must not be assumed, on the whole, that there is anything like the traditional enmity portrayed in fiIm and fiction as existing between grifters and detectives. The wrong coppers are usually too fair-minded to hate con men; they know only too well that con-game victims are fleeced while trying to profit by a dishonest deal; furthermore, they see arresting a con man and giving honest testimony against him only as a part of their sworn duty, But the wrong copper is a very rare bird. The right coppers who have been on duty for many years know all the important con men in the country and con men know all the detectives. They do not hate each other any more than a merchant hates his customers; they co-operate for their mutual well-being; it is a part of the system. . . . The wise detective causes a con man as little trouble as possible, never asks him embarrassing questions, and takes his end quietly and unostentatiously. He knows which side his bread is buttered on; he may go out of his way to do favors for those con men who pay regularly and generously, but there is nothing very personal about this action. (230-1)

International con men working in Europe, Mexico and South America report that the fix abroad works much the same as it does in the United States, and, because of the highly centralized police systems, is reputed to be even more secure than it is here. (233)

If the local police, working under the fixer's instructions, find it impossible to cool out the mark successfully, they may, as a last resort, refund part or all of his money. However, con men report that the police do not favor this node of settlement—if there is any other way out—because they must "kick back" the money which the fixer has already distributed. Often they compromise on a settlement whereby the mark is given back a part of his loss and convinced that he is very fortunate to have regained even that much. Thus the mark is satisfied, the con men and the coppers make something from the deal, and the police get the credit for obtaining and returning part of the stolen money. (234)

A judge naturally cannot guarantee an out-and-out acquittal. The evidence which gets to court in a con case is always very strong and the prosecution thoroughly embattled. But, if things look too bad for the con man, the judge can always follow the standard procedure of a St. Louis judge ("the rightest judge in the U.S.A.") who, when the con man pleaded guilty and threw himself on the mercy of the court, gave him a sentence of one year, then probated it. (238)

The short-con games are, theoretically, any confidence games in which the mark is trimmed for only the amount he has with him at the time—in short, those games which do not employ the send. (248)

Just as this is being written (November 21, 1939) the newspapers carry headlines telling of several Texas bankers who were swindled for $300,000 on the old gold brick game, a chestnut, if ever there was one. The games grow old but the marks are always new. (249)

The problem of the fix is also becoming more difficult in the age of increasing military control over civilian life. This situation will probably force many confidence men to seek other hunting grounds for the duration of the War. (311)

War profits are already finding their way into the pockets of certain European citizens who may be depended upon to make excellent marks. It is probably only a matter of time until something very similar occurs here. Thus the second World War may produce another crop of "war babies" with corresponding profits for the confidence man. (312)

There is at present a determined movement on the part of the Federal Government to cut off the wire service from race-tracks to legitimate bookmakers. Should this move succeed, confidence men, specifically those operating the pay-off, might be somewhat inconvenienced for a time. They could rest assured, however, that very shortly illicit or "bootleg" service would be common enough that the mark would not be suspicious of a big store set up with what appeared to be illegal service. It is even possible that the outlawing of legitimate track-service might work in favor of the pay-off men. (313; see Drugs, War on)

So long as there are marks with money, the law will find great difficulty in suppressing confidence games, even assuming that local enforcement officers are sincerely interested. . . . .As long as the political boss, whether he be local, state or national, fosters a machine wherein graft and bribery are looked upon as a normal phase of government, as long as juries, judges and law enforcement officers can be had for a price, the confidence man will live and thrive in our society. (314)

|