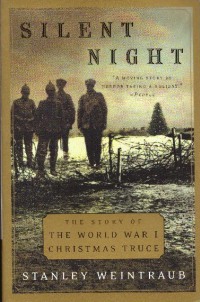

Silent Night: The Story of the World War I Christmas Truce

Stanley Weintraub (2001)

In December 1914, on both sides of the front lines in Flanders, astride the borders of Belgium and France, soldiers of two of Queen Victoria's grandsons, Kaiser Wilhelm II and George V, faced off from rows of trenches that augured a long war of attrition. (1)

Opposite, the British applauded each song, and a "big voice" responded from the German parapets, "Blease come mit us into the chorus." After a killjoy on the British side shouted back, "We'd rather die than sing German," the big voice boomed, in English, "It would kill us if you did." (13)

Rightly, the Germans assumed that the other side could not read traditional gothic lettering, and that few English understood spoken German. "YOU NO FIGHT, WE NO FIGHT" was the most frequently employed German message. (25)

A French soldier wrote to his mother that after they first met with the enemy, they chorused, each in his own language, "A bas la guerre!"—Down with the war! (32)

Toward midnight, firing ceased and soldiers from both sides met halfway between their positions. "Never," wrote Muhlegg, "was I as keenly aware of the insanity of war." (33)

Christmas helped—at least for the moment . . . to bring together men who really, they recognized, didn't hate each other. Their fraternization, dangerously unwarlike from the headquarters perspective, seemed unstoppable. (51)

Soon few would care about higher authority. (57)

In the aftermath of the failed attack, the Oberstleutnant had realized that the young officer, who lay beyond medical aid, was struggling to get something out of a tunic pocket. The German bent to help, and saw it was a photograph of the dying man's wife. "I held it before him, and he lay looking at it till he died a few minutes after." (61)

[Corporal John Ferguson:] What a sight—little groups of Germans and British extending almost the length of our front! Out of the darkness we could hear laughter and see lighted matches . . . . Where they couldn't talk the language they were making themselves understood by signs, and everyone seemed to be getting on nicely. Here we were laughing and chatting to men whom only a few hours before we were trying to kill! (79-80)

According to his diary, [Field Marshal Sir John French] "issued immediate orders to prevent any recurrence of such conduct, and called the local commanders to strict account," which resulted, he understated later, "in a good deal of trouble." (81)

A London Rifles entrepreneur, offering large quantities of appropriated bully beef and jam, acquired a prized Pickelhaube [spiked helmet], which was nearly impossible to conceal or cart home. The day after Christmas he heard someone shouting for him from the German side. They met in No Man's Land. "Yesterday," his new friend appealed, "I give my hat for the Bullybif. I have grand inspection tomorrow. You lend me and I bring it back after." Somehow the deal was kept. (86)

[William Dawkins:] "The Germans came out of their protective holes, fetched a football, and invited our boys out for a little game. Our boys joined them and together they quickly had great fun, till they (I believe we were responsible) had to return to their posts. I cannot guarantee it, but it was told to me that our lieutenant colonel threatened our soldiers with machine guns. Had just one of these Big Mouths gathered together ten thousand footballs, what a happy solution that would have been, without bloodshed." (113)

Lieutenant C. E. M. Richards of the 1st Lancashires, a career officer and later a general, was exasperated by the fraternization and longed for some "good old sniping . . . just to make sure the war was on." (113-14)

Rifleman George Eade of the 3rd London Rifles reported a German who had lived in London parting from him with "Today we have peace. Tomorrow you fight for your country; I fight for mine. Good luck." Opposite the 2nd Borderers the Germans sang "God Save the King" and from their trenches the Tommies offered three cheers. In most cases the adversaries parted as friends in the manner of pugilists shaking hands before the opening bell, but there was always an undercurrent of wariness. West of St. Yves, Private William Tapp of the 1st Warwicks observed pragmatically in his diary that the Saxons opposite "say they are not going to fire again if we don't, but of course we must and shall do." Yet he conceded that "it doesn't seem right to be killing each other at Xmas time." It was an attitude that would be parodied by a wit in the 63rd Division, who wrote,

I do not wish to hurt you

But (Bang!) I feel I must.

It is a Christian virtue

To lay you in the dust.

You—(Zip! That bullet got you)

You're really better dead.

I'm sorry that I shot you—

Pray, let me hold your head.

(133)

By now, most units faced resuming hostilities, however unwillingly. When the 107th Saxons cautioned the 1st North Staffs that shooting had to recommence, both sides showed authentic unwillingness. (140)

According to the woman to whom the German sergeant told his story. "The difficulty began on the 26th, when the order to fire was given, for the men struck. Herr Lange says that in the accumulated years [of his service] he had never heard such language as the officers indulged in, while they stormed up and down, and got, as the only result, the answer, `We can't—they are good fellows, and we can't.' Finally the officers turned on the men with, `Fire, or we do—and not at the enemy!' Not a shot had come from the other side, but at last they fired, and an answering fire came back, but not a man fell. `We spent that day and the next,' said Herr Lange, `wasting ammunition in trying to shoot the stars down from the sky.' (141)

One German explained the situation to Drummond as "We don't want to kill you and you don't want to kill us. So why shoot?" (142-3)

But perhaps more important, many troops had discovered through the truce that the enemy, despite the best efforts of propagandists, were not monsters. Each side had encountered men much like themselves, drawn from the same walks of life—and led, alas, by professionals who saw the world through different lenses. (149)

A future general, Captain Jack of the Cameronians, averse to the truce when on the line, had speculated in his diary a few days earlier, in almost Shavian fashion, about the larger implications of the cease-fire, which had extended farther than governments conceded. "It is interesting to visualize the close of a campaign owing to the opposing armies—neither of them defeated—having become too friendly to continue the fight." (160)

During a House of Commons debate on March 31, 1930, Sir H. Kingsley Wood, a Cabinet minister during the next war, and major "in the front trenches" at Christmas 1914, recalled that he "took part in what was well known at the time as a truce. We went over in front of the trenches, and shook hands with many of our German enemies. A great number of people [now] think we did something that was degrading." Refusing to presume that, he went on, "The fact is that we did it, and I then came to the conclusion that I have held very firmly ever since, that if we had been left to ourselves there would never have been another shot fired. For a fortnight the truce went on. We were on the most friendly terms, and it was only the fact that we were being controlled by others that made it necessary for us to start trying to shoot one another again." (169-70)

[Quoting from a ballad] "The ones who call the shots won't be among the dead and lame, / And on each end of the rifle we're the same."

That recognition occurs at some moment in every war, as an Australian trooper remembered in North Africa late in 1941. At Tobruk . . . for a few hours, men on both sides openly stood up, in the past an invitation to be shot. They dried their clothes, made tea, and did not return desultory fire. An infantryman looking unnaturally old after months of exposure to the cruel sun, the dust and the strain, looked across at the enemy, who were suffering in the same way, and said to no one in particular, "Nobody said we couldn't like them, they just said we had to kill them. All a bit stupid, isn't it?" (172-3)

|