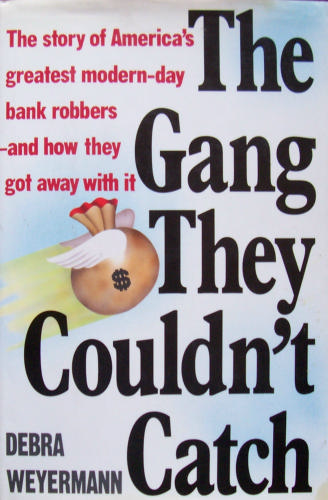

The Gang They Couldn't Catch

Debra Weyermann (1993)

Sometimes David would sit at the bus stop across the street eating an ice cream. Sometimes in the coffee shop down the way eating breakfast. But in a month or so, he knew every procedure the depository followed. He found it incredibly stupid that they followed the same routine everyday, but he chalked that up to Bud Grainger (nicknamed Bald-Headed Bud by David and his partners). From his observations, David felt Grainger was a man who couldn't stand change and was very controlling. Ordinarily, such a personality might present a problem—try some heroics. But David didn't think so in this case. Grainger seemed more at ease with bullying his subordinates. (17)

"We have to sign in," Harris heard Grainger croak. It was policy for everyone to sign in, in the morning.

"Jesus Christ, Bud," came a flat, sarcastic voice [David] Harris didn't like one bit. "Why don't we just forget about your fucking little sign-in sheet. Live a little. This morning we're gonna break the rules." (28)

Inside the vault, Doug and David watched Bud Grainger go to work on the money drawers. Both watched with increasing irritation. Grainger was fumbling and bumbling with the combinations, pretending he didn't know them. I ought'a go over there and kick him in the ass, David thought, just to knock some wisdom into him.

In all his years in the robbery business, David had never been able to comprehend people who were willing to risk their lives to save someone else's money. Their own money, yes. He could understand that. He had never robbed small businesses for this reason, though it didn't have so much to do with his fear of resistance as his feeling that it was somehow not right.

But a bank's money? Next to insurance companies, banks were the worst possible institutions in the country. They were responsible for half the wars going on around the world and they wouldn't give two nickels for a dime for Bud Grainger's life if he had begged for it. Yet here he was fumbling around, pretending he couldn't open the vault at all and then saying he couldn't open the shining steel cash drawers. (28-9)

"Bud, I want you to stop fucking with us!" Grainger heard one of the men snarl. . . . "Open those goddamn drawers on top and stop fucking around or I'm gonna blow your fucking brains out."

Grainger felt, rather than saw, the man move up behind him. The man moved closer, so that Grainger could feel his menace at his back.

David rolled his eyes under the sweaty mask as Grainger continued his pretense. And then, Grainger did what David considered to be his stupidest move so far. He started clutching at his chest and gagging.

"Motherfucker! The asshole is pretending to have a heart attack," Doug said, also astonished at the folly of it. Both men had seen it before.

In fact, Grainger was pretending. He would later testify that he'd seen the move on numerous television programs. It always worked there. (30-1)

David had always assumed he had at least two minutes to leave a robbery scene—even after an alarm was sounded and even though a cop might be having coffee next door. He believed the police would rather track robbers than engage them in a firefight. He'd had some experience with it in his younger days. (35)

At [El Con] Mall, Starr circled the van warily, noting that it was not a telephone van after all. It had only been painted to suggest one. Some psychologists, these guys, he thought. (37)

Police chief Peter Ronstadt, the brother of singer Linda Ronstadt, was at a fund-raising breakfast the morning of April 22. Ronstadt had lived his entire life in Tucson and he did not dread these necessary chicken and pea appearances anymore. At population 500,000, Tucson was just big enough to afford privacy and just small enough to require camaraderie. . . . Ronstadt's father was German, his mother Mexican. Unlike cities in the north of the state, the combination was normal, accepted, and sometimes even necessary to get ahead. Tucson was a very integrated city. Maybe it was the city's proximity to a poverty-stricken and uncontrollable border. Maybe it was the fact that the city was rough with drug importers whose business in part benefited the economy, even if bodies did turn up regularly in the desert. Maybe it was the summer heat. But Tucsonans tended to wink at situations others might stamp their feet over. They were used to the abnormal and they had a sense of humor about it. (38)

Successful bank robberies, especially record ones, do not make bankers look exceptionally competent and they encourage follow-up attempts. The depository at Broadway and Swan was razed and rebuilt shortly after the robbery to prevent information about its interior from being passed around the criminal community. (43)

The newspapers clamored daily for more details. The Tucson Citizen scored a coup when reporter John Rawlinson got an exclusive interview with [janitor & sometime hostage] Charlie Virgil. It was splashed over the front page as if Virgil were actually a president of some small country. Reporters from coast to coast began calling him, begging for similar interviews. Supermarket tabloids teased their readers with visions of the missing millions. Even Time magazine got into the act, running a breathless article that was mostly inaccurate. (54-5)

Kelly Grandstaff, one of David's brothers and a union painter, was working when his phone began ringing off the hook with newspaper people wanting to know if he had received any of hte TUCROB loot in the mail. Enraged, he called the Register, demanding that no such nonsense be printed. He had four children and he did not want every crook in the country to think he was sitting on a million dollars. The information that the loot was with "relatives" was printed anyway. The paper subsequently apologized, but Kelly, an avid hunter, spent many sleepless nights sitting up with his shotgun, listening for noises in the dark. (55)

Perhaps because farming is an intensely individual effort, Iowans have a history of distrust and scorn for authority, particularly moneyed authority. Certain types of banks were not even allowed in the state until 1858. In 1932, 1,400 farmers converged on the county seat to stop New York Life Insurance Company from repossessing a farm. They slapped the sheriff (and anyone else who tried to interfere with them) senseless. This method of averting foreclosures continues to this day. In the 1970s, when farms were failing all over the Midwest, it was not uncommon for ruddy Iowa farmers, known for their conservative morals, to drive their pickups through the front windows of banks holding notes to their farms. (64)

Many Bottoms Dwellers considered themselves "educated" if they graduated from high school, but nobody got a watch or a car or even a cake for achieving it. In some cases school was considered a nuisance, since it prevented youngsters from holding down full-time jobs. College educations were not even discussed. College was something spoiled, rich people did before going out to fuck up the world with their stupid ideas, just as they always had. (66)

The Kellogg bank robbery made headlines from coast to coast. No one had ever taken a bank manager hostage before. No one had violated a person's home since Charles Starkweather's murderous rampage, when he and his fifteen-year-old girlfriend killed her entire family and a half dozen other hostages in three midwestern states. (145)

From Clyde's perspective, the roughness had been a necessity. At age four, Doug had taken every butcher knife in the kitchen and placed them in a circle around his sleeping grandmother. The woman had awakened with a start to see her grandson rocking on his haunches before her with several additional knives stuck in his pants. He was grinning. She'd administered the usual treatment, taking the boy upstairs and wiping his anus with a piping hot towel. (182)

The take was $300,000. David was reassured to see the morning papers reporting the take at $500,000. More insurance fraud. It made him feel all right about being an armed robber. At least he was honest about it. (198)

She instructed the agents to rent cars from around town. Cars that looked nothing like automobiles commonly associated with police agencies. Even the agents joked about "heat cars"—the dark-colored, often cumbersome American sedans with no individuality to them. Even civilians could easily spot them. (231)

Bruce went in a different direction, but there were too many police and not enough places to go. Tired, frightened, and winded, he collapsed in a backyard. He was tired and sick at heart. The last six months had been a living hell. Far from being romantic, being on the run had been a nightmare of bad hotels, constant movement, and total loneliness. He missed his friends. He missed hanging around the auto parts stores, talking mindless crap. He hated not being able to show his face in familiar bars. Panting, he waited silently in the darkness. Surely they would find him. Incredibly, officers were all around him, but never saw him. He waited quietly. (233)

It was true that plenty of defendants did look unsavory. But The Boys didn't. They were well dressed. They were polite, at least in court. She knew that they were plenty abusive to the police, but she half suspected that cut both ways. But although she never really got to know Grandstaff or Brown well, she actually had become friends with some of the others. It had been a revelation to her that these people were, in fact, just like her in every way except their work. Outside of armed robbery, they were completly law abiding. They didn't even have traffic tickets.

When the decision had been made not to put the fugitives on the Ten Most Wanted List after the Tucson robbery, it had been based in part on the fact that htey had never hurt anybody physically. After getting to know Mike Gabriel, Roxanne was convinced that the last thing they wanted was to hurt people and that's why the jobs were so carefully planned. No surprises. Nobody bursting in they didn't know about, endangering the whole enterprise. Still, she'd often wanted to ask them what they would have done if problems had arisen. They went in, after all, with loaded guns. (239)

"All this moving around is fucked, David," Doug said. "Sooner or later, somebody's gonna spot you. You better just go lay down like you planned. At least until they forget about this thing."

"They ain't never gonna forget about this, Doug. This is dollar justice we are talkin' about. You can rape their daughters and beat their sons and they'll give you five years. But, by God, don't take their money. That's an automatic twenty-five to life. I done time in the joint with guys that had crippled people for life and got out long before I did. Believe me. They ain't gonna forget." (251)

At the desk, clerk Ron Davis's hands were trembling and his shirt was sweat-soaked. The man could not seem to concentrate on getting the change right and kept recounting it. The head clerk, Bernie Mustoe, seemed to keep stepping backward, as if to be ready to turn and flee to the office behind him at a moment's notice.

David was disgusted with the FBI. What purpose did it serve to scare these poor shitkickers to half to death with tales about what a dangerous desperado David was? He was sure they'd told him that he carried machine guns and hand grenades and wouldn't hesitate to cut the guy's throat. These poor saps were terrified so that some agent could feel important going through the whole routine. David thanked Davis in a gentler voice than he usually employed and turned toward a hallway that led outside. (253)

David saw drawn guns and the blur of movement before he was overcome by a web of grappling arms. He knew who they were, but anyone else might not have, since they didn't announce it. It was annoying. Also, his attempts to inform them that he was not armed were drowned in all the screaming they were doing. Everyone was yelling at once, which made David wonder what they ever learned in their academy. Several agents tripped over one another's feet and went sprawling across the floor long before they finally got David facedown on the carpet. He didn't understand why they wanted him on the floor in the first place. He hadn't put up a fight. (254)

Doug knew the script immediately, but it was clear Lisotto was thunderstruck. Doug hated it when cops became thunderstruck. They tended to overreact and shoot people. Lisotto just stood there with wide eyes and his mouth trying to work and it took a few seconds for his hands to respond to brain commands to go to his holster.

Before he could do that, Doug had his hands up in a nonthreatening way and was saying, "Be cool, man. Be cool." He was gratified to see it work and gladly knelt on the floor with his hands clasped behind his head when Lisotto told him to. Had he been armed, it might have been different, but as it was, he joined David in the Denver County Jail directly. (255)

Hirsh sometimes used psychological firms to evaluate potential jurors. He had in this case. They had pretty much come up with the obvious. No bankers, no Nordic people, no stockbrokers. We need people who question authority. Nonetheless, Hirsh did what he always did and went with his own opinion. He put a bank teller on the jury. His reasoning was that she was Hispanic, had probably never been given a raise in the seventeen years she'd worked for the bank, and would be happy to know somebody had robbed one. (302)

Rocking in his chair, David wondered how many times and at how many parties Grainger had told the story of his harrowing bruch with death. Probably added years to the guy's life, David thought. Given him something to live for. (322)

Arriving at the far end of Tucson International's runway, George saw a large bus, a half dozen marshals' cars, and the heavily armed officers, the desert sun glinting off their upraised shotguns.

"Jesus," White said, leaning over George to peer at the spectacle. "What creep do you suppose they're expecting?"

It had not occurred to George, either, that the welcoming party was for them. (324)

As it turned out, the jurors had reached a unanimous not-guilty verdict on the first ballot. They took a few more, but they always came up the same. Somewhat giddily, they decided to send out for evidence, just to make it look like they were thinking on it. They never looked at the evidence on the table except in passing.

While they whittled away time, it came out that they hated [stoolpigeon] Bruce Fennimore, couldn't stand the FBI agents and how they'd comported themselves, and had smelled, vaguely, the scent of a setup. They weren't that crazy about the bankers, either. Leaving the courthouse, the juror who had been a bank teller for seventeen years beamed for the cameras and announced, "I knew those boys were innocent all along."

"Were they guilty or innocent?" a reporter asked [jury foreman] James Rice years after the trial. He shifted uncomfortably at the kitchen table where the interview was taking place. His wife, Barbara, looked at him expectantly. He dodged the question.

But forty-five minutes later, after he was a little more comfortable, he said, "I never thought David Grandstaff, Doug Brown, and Bruce Fennimore divided that money equally." He shook his head as if considering the wisdom of this. "Anyway, I hope they're enjoying it." (343-4)

|