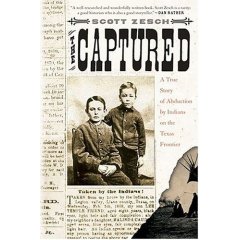

The Captured: A True Story of Abduction by Indians on the Texas Frontier

Scott Zesch (2004)

Some of the neighbors offered to ride with him. However, when Captain Williams asked one smart aleck in the Saline community to join him on the Indian hunt, the man refused, saying he hadn't lost any Indians. (11)

One Comanche captive, Clinton Smith . . . reported that the Comanches sometimes chased settlers into their shacks just for fun. When the white family in his story sprinted to their cabin . . . "[w]e all gave the war-whoop, just to see how fast those people would run. . . . We had a big laugh." (13)

Banc had made up her mind not to cry. Later, her captor, whose name was Kerno, told her that if she'd cried, he would have killed her. (44)

They wouldn't let the three prisoners off their horses during the flight. The girl captive, Banc Babb, lost control of her bodily functions. The Comanches must have been amused, for they gave her a nickname that meant "Smell Bad When You Walk." Unfortunately for Banc, the name stuck. (45)

As Banc later related, "I was so hungry that I begged for some of the raw meat, and they gave me a small piece, which I ate greedily and begged for more. . . . I reached for a piece myself, when an Indian hacked my finger with his knife. I reached with my other hand and he hacked it, so I decided to quit reaching." (46)

Persummy . . . claimed Dot as his own but placed him in the home of his sister and her husband, Watchoedadda (Lost Sitting Down). Dot was given an equally unflattering name: Nadernumipe (Tired and Give Out). (53)

One day Persummy, painted and bedecked in horns and feathers, told Dot to follow him into the sand hills for a demonstration. He then handed Dot his six-shooter, instructing the boy to fire at his torso each time he charged and at his back each time he retreated. If Persummy was testing Dot, he did so at great personal risk. He made four charges and retreats. Dot fired six shots, and each time Persummy deflected the bullets with his buffalo-hide shield. Afterward, rather than gloating over his own skill and bravery, Persummy complimented Dot on his accuracy and said he would make a trustworthy warrior. (53)

In exchange for the concessions forced on these tribes, the government promised to provide them with houses, farms, agricultural implements, schools, churches, teachers, carpenters, doctors, and all sorts of things they didn't want. (66)

It wasn't until she got inside that the Bradfords saw how horribly she was wounded. The sight of Matilda Friend--two arrows sticking out of her, oozing from her scalp and down her face--caused them to panic. They were sure the Indians were still in the area and would come for them next. The Bradfords decided that they weren't going to ride for a doctor, sit with Matilda and comfort her, or even take time to removed her blood-soaked clothes or dress her wounds. What they did was place her in front of the fireplace and quickly retie her bleeding head. They put a bucket of water by her side and threw a quilt on the floor. At Matilda's insistence, Jack finally agreed to extract the arrows, cutting them below the feathers and pulling them through. Before they abandoned her, the Bradfords told Matilda not to lie on their bed; they didn't want their linens bloodied. Then Jack and Samantha woke the children and fled with them, leaving their cousin alone to die. For the rest of that freezing night, the Bradford family hid in a cedar thicket. (74)

One night Minnie was nearly trampled by accident. Her great-granddaughter, Neoma Benson Cain, remembers her telling the story: "She said that the Indians were real jokesters. They'd stampede their own horses right through the camp, and just laugh! One of the horses stepped on the edge of the tepee, and it grazed her head. From then on, she always put her bed away from the wall." (81)

The Wynkoops were a dashing couple. He was a social, polished gentleman, an amateur actor, and, according to the British journalist Henry Morton Stanley, a "skillful concoctor of drinkable beverages." (83)

One day the Indians sent Minnie and Temple to the river to fill a wooden bucket with water. The stream was shallow, and they took turns using a tin cup to dip the water into the bucket. Temple was playing along the edge of the stream. Minnie got tired of doing all the work and handed Temple the cup. They got into an argument. Temple swung the empty tin cup and hit Minnie in the stomach.

When they got back to the campe with the bucket of water, the Indians ushered them to the tepee of the group's headman. He was sitting inside, slowly drawing the blade of his knife back and forth across a sharpening stone. Suddenly, he grabbed Temple by the hair on the back of his head and laid the boy across his knees. He pressed the blade of the knife against his neck. Through signs and gestures, he made them understand that he was going to cut off Temple's head for hitting Minnie. The terrified children started wailing and pleading for mercy. Eventually, the man made Temple understand that if he'd never strike Minnie again, he would let him live.

That was the only time the children were afraid of the Indians in camp. Later, Minnie and Temple came to realize that the man was just fooling with them. Considering what they'd witnessed during their flight from Legion Valley, no one could blame them for taking him seriously. (80)

Dot watched the Comanches stab, shoot, and scalp his mother. Minnie was present when her captors brutally terrorized, raped, and butchered her half sister, niece, and three cousins. Even though her Comanche mother shielded her from some of the worst sights, she said: "I remember how they suffered. They cried and prayed all the time and they knew they were going to be murdered."

Historian J. Norman Heard, who studied more than fifty captivity cases from across America, observed: "Frequently, the surviving members of the family were compelled to carry the scalps of their parents and little brothers and sisters, an experience which would seem likely to have instilled in them such a hatred of Indians as to make assimilation impossible." Yet that wasn't the case. Minnie Caudle's great-granddaughter, Neoma Benson Cain, recalls, "She would not hear a word against the Indians." (85)

Willie would later summarize his four-day captivity as follows: "During my stay with the Indians I was never whipped or beaten, and besides scares, hard rides and starvation, I was treated well." (97)

The Southern Plains Indians lived under mean circumstances in a merciless environment. They were passionate and affectionate, but they weren't gentle people. They had to be tough to survive, and they raised their children to endure great hardships. For the most part, they didn't treat their boy captives any more harshly than they treated their own sons. When Herman Lehmann described how the Apaches taught him to swim by simply tying a rope around his body and tossing him into a pool of deep water, nearly letting him drown while he floundered, he concluded: "The Indian boys were taught by the same process." Roughhousing and deprivation were just part of their training. And the fighting men, hoping to build up their own ranks, were determined to make Indians out of those white boys who could take it. (102-03)

By the spring of 1871, when Clinton and Jeff Smith were captured, Rudolph Fischer of Fredericksburg and Temple Friend of Legion Valley were already full-fledged Comanches. Adolph Korn, Herman Lehmann, and the Smith brothers had all passed the initial trial by fire. These timid farm boys were well on their way to becoming juvenile Indian warriors. No one has ever come up with a completely satisfying explanation for how that happened. Anthropologist A. Irving Hallowell pointed out in 1963 that Indianization "has remained a neglected topic of scholarly research," and this is still the case; most recent scholarship in this area has focused on the captivity narrative as a literary genre rather than the psychology of the captives' transformation. (111)

Ironically, captivity opened up a new world of freedom for some overworked farm children, who had previously spent their days herding livestock or hauling rocks or hoeing fields. (114)

White boys who'd spent much time with the natives had a reputation for being crueler to their fellow Anglos than the Indians were. (120)

It wasn't unusual for captives such as Adolph Korn to take greater chances than the natural-born Comanches. This may have been a matter of conversion zeal. Herman Lehmann, for instance, proudly proclaimed that he was the "wildest of the wild" when he was with the Apaches. The white Indians were also said to be crueler in initiating newly abducted captives than were their fellow tribesmen. (123)

The Plains Indians conferred nicknames spontaneously, and the ones they came up with were seldom heroic. In fact, some of them seem to have been intended as ribald jokes, memorializing a humiliating incident or characteristic. Anthropologist E. Adamson Hoebel, who interviewed many Comanches in the 1930s, quoted tribal members with sobriquets as inglorious as A Big Fall by Tripping, Breaks Something, Face Wrinkling Like Getting Old, Not Enough to Eat, She Blushes, and She Invites Her Relatives. In the nineteenth century, Southern Plains tribesmen rose to influential positions despite having been saddled with epithets such as Always Sitting Down in a Bad Place, Dog Eater, and Coyote Vagina. I was pleased to find that the Comanches I met in Oklahoma maintained a healthy sense of humor about their ancestors' nicknames. They assured me that I shouldn't feel disappointed to be a lateral descendant of a young warrior with a name as ordinary as Not an Old Man. (127)

Only Herman Lehmann wrote frankly and unapologetically about his amorous adventures, first among the Apaches and later with the Comanches. As he explained, "With the Indian, all nature took its course, and we had none of those abnormal hugs on the sofa in a dimly-lighted parlor." At the same time, he was careful to point out, "There was virtue among the Indians and it was rigidly maintained." (132)

One night Herman arranged to come see Topay at about eleven o'clock. He crawled inside her tepee and "found her awake ready to receive" him. He was "whispering sweet words of love and encouragement to her" when he felt a rough kick in his behind. Topay's father was standing in the doorway. Herman promptly bounded out through the tepee wall, "leaving a pretty considerable hole in the tent." As Herman circled the tepee, he came face-to-face with the girl's father, who shot an arrow that struck Herman's knee. Topay sprang from the tepee and took him in her arms. She rebuked her father for treating him that way. "He was behaving nicely," she scolded, "and you should not have disturbed us." Her father calmed down, apologized, and removed the arrow from Herman's knee. (133)

Then the Apaches headed north to Loyal Valley, where Herman's family lived. There, the raiding party stole his former neighbors' livestock. As Herman related, "We passed right by my old home, and the Indians tried to get me to go see my mother. They called me paleface and urged me to quit them." Herman refused. (135)

Mackenzie's men poured into the camp. Famished from their long ride, they helped themselves to some of the Comanches' dried buffalo meat. Sgt. John B. Charlton noticed a different type of meat of a lighter color on one rope and ate some of it. He handed it to the chief of the Tonkawa scouts and asked him if it was pork. The Tonkawa tasted it, and said, "Maybe so him white man." The Comanches weren't cannibals, and Sergeant Charlton must not have realized that the poker-faced Tonkawa was pulling his leg. He doubled over and vomited. (165)

On October 30, the [Comanche] delegation visited the Church of Our Savior on East Twenty-fifth Street, where the Episcopal Board of Missions was meeting. The Indians were decked out in feathers and paint; some carried their arrows and tomahawks into the sanctuary. The Episcopalians, excited to have such exotic potential converts in their midst, serenaded them with the missionary hymn "From Greenland's Icy Mountains":

From many an ancient river,

From many a palmy plain,

They call us to deliver

Their land from error's chain.

Can we, whose souls are lighted

With wisdom from on high,

Can we to men benighted

The lamp of life deny? (172)

That afternoon the Indians attended the circus on East Thirty-fourth Street. Unimpressed, they scowled throughout the performance. Although the Comanches loved to laugh, they found the clown's tricks entirely unfunny. That night they saw a Broadway show at Booth's Theatre; the press reported that they "conducted themselves in a Christian-like manner, never applauding and being very silent." (173)

Adolph wasn't ready to recognize the Korns as his people. For three years, Louis and Johanna Korn had prayed that someday they might be reunited with their son. That day had arrived, but instead of bursting with unbridled joy, they felt the onset of a new kind of heartsickness. Their boy was back, and he hated them. (192)

It took Clinton and Jeff about a year to get used to being around white people and to lose their fear of them--much longer than it had taken them to feel comfortable with the Indians. (200)

Within a year or two, the former captives more or less settled down and learned to curb the extremes of their unconventional behavior. Nonetheless, a part of them would always belong on the other side. They had spent their formative years in two very different cultures, Native American and European-American. The tension between those competing ways of looking at the world--both of which were deeply engrained in their characters--would cause more problems for the former captives attempting to reconnect with their own people than for their Indian friends who tried to walk the white man's road for the first time. (201)

Ishatai [Coyote Vagina] watched the debacle from the plateau. Too late his followers realized that they'd put their trust in a charlatan. One Cheyenne told him bitterly, "If the white man's bullets cannot hurt you, go down and bring back my son's body." Another Cheyenne named Hippy grabbed the bridle of Ishatai's horse and tried to use it as a quirt on him. Then came the medicine man's greatest humiliation. A stray shot killed Ishatai's horse, which he had coated with his special protective paint. (207)

During the remainder of 1874, Col. Ranald Mackenzie kept the Quahadas on the run. He had resolved to drive them onto the reservation and force them to surrender. That fall the weather was unusually wet, and the Comanches referred to the miserable pursuit as the "Wrinkled Hand Chase." (208)

Nothing looked familiar to Herman. . . . At first Herman refused to step down from the ambulance. When he finally alighted, Auguste ran up to him, threw her arms around his neck, and started weeping. He didn't know her and grunted in disdain. To him, "she was no more than a white squaw." The crowd spoke excitedly in German and English, languages Herman couldn't understand. Some were laughing, some crying, some shouting praises to God and singing hymns of thanksgiving. Their emotional outbursts irritated him. "Pshaw!" he wrote. "I did not approve of such conduct, so I broke away from them." He tried to walk off, but the soldiers stopped him.

Someone kept saying, "Herman. Herman." The name had a familiar sound. All at once he realized, to his horror, that he really was among his own people. "But," he explained, "I was an Indian, and I did not like them, because they were palefaces." He lay down on a blanket in the yard, drowning out the noise of their church music by singing Indian songs to himself. (232)

About a year after Herman came home, his mother enrolled him in the local school. He hated it. Herman was twenty years old and couldn't stand being confined. Finally, he told his mother that he was going to tear down all the lattice in the schoolhouse so he could see out. She never made him go back. His teacher at Loyal Valley, John Warren Hunter, wrote, "As one in prison, he pined for the companionship of his Indian friends, and their manner of life." (233)

"I don't remember him doing any kind of work," says Esther [Herman's niece]. "He wasn't successful at anything." She adds, "They should have brought him back and let Grandma know he was all right and left him with the Indians. He would have been happier." (241)

The thirteenth annual reunion of the Old Trail Drivers Association got under way on October 6, 1927, and it would prove to be the humdinger of them all. . . . As one San Antonio newspaper announced, "Real Comanche Indians were brought here for the show." Thirty-seven Comanches traveled all the way from Oklahoma to portray the antagonists. . . . They were described as "giants of men, six feet and over and weighing 200 pounds." . . . The show featured an attack on a wagon train by the Comanches. They captured a white girl, played by Edith Kelley, the daughter of a trail driver. . . . Clinton and Jeff Smith attended the pageant. While they were waiting for the show to start that night, they noticed three Comanches around their age gearing up to attack the wagon train and then get killed by cowboys. They wore feathers and elaborate buckskin outfits. Clinton stared at them, with his hand cupped over his mouth. He nudged Jeff and murmured, "Look! Look at those old bucks over there! Ain't them . . ."

The Comanches glanced their way. They studied the Smiths.

A moment later, the Comanches let out loud whoops of joy. They called Clinton by his old name, Backecacho. He answered them in Comanche. The three Comanches hadn't seen Backecacho since he was taken from their camp and delivered to Fort Sill in 1872. In full view of the crowd, he and the Comanches rushed toward one another, hugging and pounding one another on the backs.

It's doubtful whether Clinton, the three Comanches, or the audience in San Antonio fully appreciated the bizarre irony of the moment: Comanches traveled to Texas to reenact the kidnapping of a white child, only to be reunited with a real captive their fathers had abducted and brought to their village. A few years later, a meeting like that could no longer take place. As one newspaper noted sadly, each year a few more folks such as these went "up the trail from which there is no return." (275)

Even though Jeff had lived with the Apaches, he was almost as excited as Clinton to be back in the company of Comanches his own age. That night he asked his son, Bert, to drive him to the Comanches' camp. "We were there all night," Bert recalled. "He was like a young man again, smoking their pipes, chanting and dancing with them. I don't think I'd ever seen him so happy." (273, 274, 275)

|