Conversation with a Tape-beatle

(Published in X Magazine, may1995 and Planet Magazine, 18jul1995)

Deuce of Clubs: Before I get to specific questions, perhaps

you'd like to recap your life/lives up to the current day. Well, okay, not so

much as that. Just whatever you'd prefer to have mentioned in the

introduction (a list of projects—CDs, Retrofuturism,

whatever—that you have done or participated in . . . that

sort of thing.) For example, Mark Simple mentioned that you are now down

to three Tape-beatles, so a personnel list would be helpful. Then

we'll get to the sexy stuff.

Lloyd Dunn: I helped found the Tape-beatles in

1986. Our (transient) membership includes: John Heck, Ralph

Johnson, Paul Neff and Linda Brown. John now lives in

Prague, Czech Republic and Ralph is studying composition at Mills

College in Oakland, Calif. Paul has quit the group and therefore

only Linda and I remain in Iowa City.

|

|

The 60s original plagiarized by the Tape-beatles

|

I have been active in the "zine community" since 1983, when

I started publishing PhotoStatic Magazine, devoted chiefly to

xerox art. Retrofuturism, the "hypermedia magazine of the Tape-

beatles" was founded in 1987. I have also published YAWN (a

newsletter devoted to the Art Strike 1990-1993) and The Bulletin of

the Copyright Violation Squad [CVS Bulletin] which reports on

copyright issues as they affect cultural workers. [There

have been 40 issues of PhotoStatic, 17 of Retrofuturism, 38 of YAWN,

and 1 of the CVS Bulletin.]

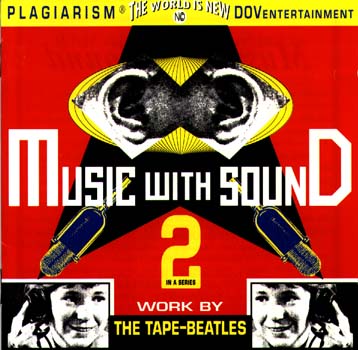

The Tape-beatles have released three major works since 1988,

which include:

A Subtle Buoyancy of Pulse cassette only, self released,

1988 Music with Sound cassette self released, CD on

DOVentertainment, Toronto, 1991 and The Grand Delusion cassette self

released, CD on Staalplaat, Amsterdam, 1993. The cassette differs

substantially from the CD so they are really to be considered

separate works. We also have a cinematic presentation using

some of this audio in conjunction with three 16mm movies shown

simultaneously which we use as our "performance."

I should note that I will be answering all the questions

myself from my perspective; perhaps the other Tape-beatles would

have somewhat differing takes on these discussions.

How would you encapsulate the central purpose behind the

efforts of the Tape-beatles?

We got together in 1986 to pursue what we thought of as a

new form of audio production: using the principle that anything that

could be put on tape had potential musical usefulness. We felt

that audio tape was a medium that had not been thoroughly explored

artistically, and we wanted to do that in a sort of pop

music context. We were, for the most part visual artists dabbling

in what was for us a new medium. We wanted a fresh, lively sound and

we wanted real content that everyone could relate to.

Over the years since 1986 we have taken on the related

project of liberating sounds and images from copyright strictures,

believing them to be inherently fluid and transitory in nature, and

thus, in some deep sense, un-ownable.

Our purpose is to make, first of all, good "music" that is

fun and interesting to listen to, and second of all, to put that

labor at the service of ideas that we believe in. It should be clear

from our work what we believe in.

Describe the perfect world, from the Tape-beatles' point

of view. For example, would plagiarism be widespread? Would

there be copyright laws at all?

I think we already live in the "perfect" world, by

definition, as this is the one we've received, "ready made" at the moment

of our coming into it. The word "perfect" means little more than

"finished," really, particularly if you examine the words

derivation from the Latin "per-" an affix that refers to

through, or thoroughness, or completeness; and "-fect" a variant on

the past participial form of "facere," to make or to do; therefore

something that is "perfect" has been "made thoroughly" and nothing

more can be done to improve it.

This is not to say that the world cannot be improved, but

begs the question, who is in the best position from which to improve

it? Clearly, the answer is not "artists," but at the same time,

artists do have a certain kind of power over messages, the ability

to present them well and convincingly, putting their aesthetic

sensibilities and training at the service of getting

messages across. The simple answer to the question "Why am I an

artist?" is that I believe I am well suited by predisposition and

sensibility to be an artist. If I were better suited to be an

accountant, no doubt that's what I'd be. It makes me happy if I feel my

inborn talents are being put to good use.

Back to the idea of improving the world; well that's a scary

project, isn't it? How do I know my ideas are actually going

to fix things, or make them worse? I don't. But paralysis is much

more wasteful than trying and failing. So we do try. In part it's

vanity, because we feel like our ideas hold the key that

everyone is looking for; in part it's self-interest, because we want

to live in the better world we are trying to bring about; but it

adds up to a project that at least strives for something good, as

opposed to being destructive.

As for "wanting" plagiarism to be widespread, I don't really

think that plagiarism is the real issue. The issue is whether or

not we have some dibs on the environment we live in, whether or not

the airwaves and our culture are in some way "ours, too" and

therefore resources to be utilized, not shackles for the mind and

spirit. I want people to feel this way about their culture; whether or

not they plagiarize is beside the point.

Compare and contrast: (1) the meaning of sampling as it

is practiced by the Tape-beatles and (2) the meaning of

sampling as it is practiced by rap artists.

I can't speak to how rap artists use "sampling"; although

sometimes I enjoy and admire their work, I just don't know enough

about it.

For the Tape-beatles, we don't "sample," we steal. The

difference is probably very subtle. We're not just trying to make new

sounds out of old ones (although that is part of what happens in

our work) we are trying to say that these sounds are just as much ours

as they are anyone else's. It's a refusal, you see. It's us

refusing to become mere recipients of culture; we want to be cultural

producers as well. In short, we want to participate in

culture and not just sit on the sidelines and watch it go by.

What I meant by my previous and (I now see) imprecisely-

framed question, was, roughly, this: you are opposed to the

existence of the private ownership of sounds; if your ideas about

intellectual property were to win out, to gain wide currency and

acceptance, what would the world—or, more specifically, the world of

recorded and published works—be like? For example, how would

artists be compensated for their work? Or would they?

What I'm getting at is whether what you do is really as

radical as it might sound to some ears (when you say, for example,

"we are trying to say that these sounds are just as much ours as

they are anyone else's") or whether it is merely another form of a

long-established and accepted practice—namely, the idea of

"fair use" as it applies in literary matters. Words from a

published work may lawfully be cited in their original form in the

work of another author. For example, Author Smith, in his

nonfiction work, may legally cite passages from a short story written by

Author Jones. Smith might be using the passages from Jones's work

to help support a position contrary to the one held by Jones—or

even merely to ridicule Jones—but Jones can't do anything about

it. That's "fair use." On the other hand, if Smith simply

reprinted Jones's short story and signed his own name to it, that

would be plagiarism.

In the musical realm, it's the difference between

sampling and bootlegging. It seems to me that the Tape-beatles perform

the aural equivalent of literary citation. You make use of

media artifacts, but you don't really plagiarize them. It would

be plagiarism if you merely copied, say, Vanna White's tape and

distributed it as your own. Instead, sampling from her tape

is, in effect, the same as "citing" it, by way of making a comment

on it. When someone takes sounds from the work of other artists and

incorporates those sounds into another—a different—work,

I think of that as the equivalent of a literary citation. You

haven't disputed the ownership of the artifact, you're just

reserving the right to comment upon it.

If you'll be good enough to comment on all that, we can

just pretend it was a question. . . .

Good enough. My previous answer was a bit of a knee-jerk

confrontational one at that. I appreciate the opportunity to

clarify.

Well, yes, "fair use" is well established in the literary

world and some of its aspects clearly apply. We do in fact "reserve

the right" to comment on the sounds of the world, including

those that are "owned". But we like to think that we are taking this

one step further, which is to say that we "reserve the right" to make

works that are entirely constituted of such "quotations." This

is practically unheard of in the literary world (or am I

mistaken?). (John Oswald has referred to this practice as

"electroquoting.")

To put a finer point on it, we do, in fact, dispute that

"ownership" as such of the sounds in our cultural

environment (however much we might not be able to dispute its "origin".)

You see, we believe that when works are put before the public,

then the public comes to "own" them in some deep sense. This sort of

"ownership" goes far deeper than the kind of ownership that

says that you have the "right" to this work and what is done with

it. The main confusion that we want to clear up is the confusion

that exists in many minds between the object the "culture"

resides on and the culture itself. Can you imagine ASCAP or BMI suing

you because they caught you humming that catchy little tune you

heard on the radio? Well, they attempt to sue bars and restaurants

all the time for playing their records on "public" jukeboxes, or

even radios in these public establishments. (I read about it in

Rolling Stone.) Once it's in your head (the song, the beautifully

worded phrase from that novel you're reading, that memorable scene

from a movie you once saw) it's yours, it's a part of your life.

Copyright law says that when you buy a book or a record,

it's yours except the information is not yours. You can burn the book

or use the record for a wall hanging; the object is yours to do

with as you wish. But copyright law says that the very reason you

bought the item —the information— is not yours. You can't do with

it as you wish. Use it for another purpose. Make something new out

of it. This is what Negativland calls "an uncomfortable wrenching

of common sense."

We say that there are honest ways to make use of this

cultural information that copyright simply disallows. They've used a

sledgehammer when a scalpel was required. Copyright exists

to protect—not works of culture—but rather markets.

Copyright protected works are supposed to be protected from theft, the

wilful dilution of a creator's rightful market. But "plagiarism" of

the kind we do dilutes no one's market. No one would confuse a

Tape-beatle record for a Igor Stravinsky record. No one would buy

ours instead of his, thinking of it as a substitute.

Understanding that they are separate, unique works, they might, in fact, buy

both records.

If we use a Madonna fragment on one of our records, Madonna

is not harmed in any way, nor is she deprived of any rightful

income. Nor is her reputation damaged by our re-use of "her" sound

(unless we lampoon or satirize her, which is constitutionally protected

free speech (ask Justice Souter)).

There are lots of arguments on both sides. The other side is

missing the point, I think, when they talk of creator's

rights. The other end of the trajectory has rights, too. In fact, we

believe they have the duty to look critically at what's piped into

their homes and create a constructive experience out of it. We

believe we're being constructive in our uses of others' works.

Our work probably isn't all that radical; after all, "there

is nothing quite so radical as common sense."

I want to return to the themes we've been discussing, but

first, a strange interlude of softball questions:

One of the voices on Music with Sound's "Whole New

Animal" sounds like the same guy on one of the tracks on Byrne-Eno's

My Life in the Bush of Ghosts—is it?

I guess it's possible; we got the voice from a tv

commercial, some tire company was awful proud of its new tread design.

Although I've heard "Bush of Ghosts," I'm not familiar enough with it to

pinpoint the track you describe.

"Animal" started out as a sketch from the very earliest days

of the Tape-beatles, in 1987. Ralph later added the newscaster

voices (Dan Rather, et al.) and beefed up the complexity of the sound by

laying the music on top of itself out of register (to play with the

phase).

Have the Tape-beatles ever sampled Negativland, or vice

versa?

We haven't and they haven't, to our knowledge. No particular

reason for that I suppose, other than the fact that their work is

pretty completely processed and mixed to begin with. We tend to

isolate relatively simple sound elements from records and combine

them, elementally. If a source has too many things going on in it

at the outset, it's often hard to add anything to it and have it

sound like anything. Any complexity or density you hear in the

sounds of our works usually come from us, and not from our sources,

because we've layered the sounds from different recordings or

different parts of the same recording.

What's your favorite record that you bought at a thrift

store or garage sale?

It's one that we've never sampled from, a Vol. II from

Dioris Valladares y su conjunto typico. It is a meringues record,

energetic and brassy, sort of sweet dance-rhythm love songs.

The grooves on it were absolutely gouged but I love it. The

tracks are too good to improve upon, so we've left it alone. We have

an Esquivel record in "Stereo Action." The liner notes describe

a recording technique of setting up two orchestras, one for

each channel, in different studios at opposite ends of the

building (to eliminate cross-talk). The record was done in some sort of

live mix and some of the instruments are in crazy motion all the time

across the stereo field. A very un-natural sounding use of stereo.

We've sampled quite a bit from that. Most thrift store records are

ultimately disappointing, though. You see this outrageous

cover art or bizarre liner notes, get it home, and find that there's

really not much you can do with the sound. But it's worth the

search.

Name some representative Tape-beatles day jobs.

Lloyd works in a copy center at the University of Iowa.

Linda, also employed by the University, works in the Hospital graphics

department. John is now living in Prague, but waited tables

while he lived here. Ralph is studying composition at Mills

College, but was a secretary while here. Paul worked in a sheet music

store; currently he studies Library Science and works in the

Government Documents section of the University Library.

Earlier you said, "we feel like our ideas hold the key

that everyone is looking for." What key do you mean?

I said that? It sounds pretty self-aggrandizing, in a way. I

don't recall what the context was, but I'll strike at that pitch

in a few ways.

I think probably that most of us have felt a mild resentment

at seeing copyright notices on everything and saying to

ourselves, "Well, I bought it didn't I, I'll be damned if this is gonna

stop me from copying this CD for my friend," or whatever. The Tbs

are not the only ones saying that copy-right laws are completely

unrealistic; they've been thoroughly outstripped by

technology; that the people who made the laws don't really seem to

understand how technology works and what it's really good for. So the

Tbs are the embodiment of an attitude about copyright and an example

of how copyright laws ring hollow in the light of our works, which

are plainly plagiarized, and yet original, as well. Would a

lawyer maintain that we as Tbs are not allowed to express ourselves

in this way? It might be that there are first amendment issues

here, too, but I'm not sure how willing I am to push that concept.

Another idea that figures strongly in our work is the

do-it-yourself notion that was an outgrowth of punk. We have

made most of our stuff on analog home stereo equipment that most

young Americans have access to anyway. So we want to take the

means by which corporations pipeline culture into our homes and turn

those means into devices of production of our own culture. This is

a key concept for us, too. It's a kind of electronic "folk art" if

you will. We rejected the notion that cultural production is

purely the domain of "professionals" and decided that we have something

to say, too. Along the way, we've acquired only those skills

we've needed to produce our work, striving diligently not to get

lost in the technique, which has a great deal of seductive potential

of its own.

Aside from intellectual property, what are your thoughts

on property in general?

I'd be the first to admit that property is not going to go

away. I for one like the comfort of the space I've created for

myself, and the objects I've placed within it. I need that stability in

order to be creative. I don't think it's necessarily bad to own

things. But I do think it's somewhat dangerous the way in which our

culture glorifies ownership as its own reward, and the way in which

we are encouraged to apply status to individuals who simply own a

lot of things and do little with them. Freeing people from the

requirement that they need to grow their own food and scratch out their

own existence is one of the gifts that civilization brings. It's

a good form of progress, one from which we have the capability to

benefit. It allows me the time to do what I do, which is to attempt

to make people more aware of their cultural environment. Living

simply and "primitively" no doubt has its rewards, too, so don't think

that I'm knocking it.

James Brown has asked rappers not to sample his work in

songs that glorify drugs and gangs. If an artist you had sampled

heard about it and (for whatever reason) asked you not to, would

you honor that request?

It depends on the nature of the request. It seems that James

Brown is making some attempt to be socially responsible, and the

way you've phrased it, it sounds like he's giving rappers the

freedom to sample his work if they choose. We like to think that we

sample from a position of respect, and so if the request were

respectful and reasonable, we would probably honor it.

I was in Tower Records a couple years or so back when I

actually heard the Tape-beatles playing. I asked the surly record

store clerk type about it and his response was on the order of

"Uh, wuh? Tape who? This is The Orb, dood." I'm interested to know how you felt

being sampled, and whether The Orb asked permission?

I had heard that the Orb had sampled us on one (or more) of

their cds, but haven't actually heard the work. We were a bit

taken aback that they had apparently (we were told) used our work with

little or no modification (depending on how true what we were told

is). But we're not upset about it; in fact we are somewhat

flattered. We would have been happier if they'd turned it into something

that obviously was taken from us, but was nonetheless The Orb's

work. But we might be able to get some notoriety out of it anyway,

somehow, especially if people like you make a big deal out

of it in print.

No, the Orb did not ask us permission, nor did they inform

us of what they had done (in spite of the fact that our phone

number and address appears on all of our releases).

[From the Tape-beatles' liner notes accompanying 1991's

Death of Vinyl compilation CD: "The LP and the CD are all but

irrelevant to those with the will to make their own music

and share it with the world."] I was a little confused by this; given

your group's name it isn't surprising that you would favor tape,

but given the nature of what the Tape-beatles do, don't you

need LPs and CDs—as well as television and radio (to "plunder," I

mean)?

The text from the Death of Vinyl comp was intended to

lionize the cassette as the most pervasive audio medium of recording in

the world. I was just making a point—within the narrower

confines of my earlier passion, networking—that the cassette is the

medium of choice for the small independent producer that can make

music but can't scrape together the bucks to do a mass release.

Clearly the LP and the CD are not irrelevant at all, but it often

seems like they are to some of the small producers that I've run

into. (Most of which are not media plunderers.)

Are you still publishing?

No, I stopped publishing over a year and a half ago. It was

time for me to turn my attention to other issues (I had published

PhotoStatic Magazine, Retrofuturism, YAWN, and the CVS

Bulletin over a ten-year period starting in August, 1983.) A lot of

back issues are still available.

Lloyd, thanks for your time and for your thoughtful

answers. Best of luck.

Thanks for the interview; you wrote good questions.

© Deuce of Clubs

|