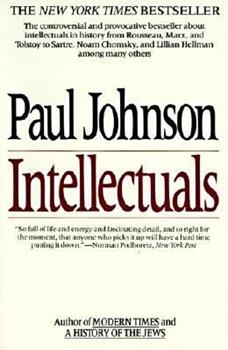

Intellectuals

Paul Johnson (1989)

Over the past two hundred years the influence of intellectuals has grown steadily. Indeed, the rise of the secular intellectual has been a key factor in shaping the modern world. Seen against the long perspective of history it is in many ways a new phenomenon. It is true that in their earlier incarnations as priests, scribes and soothsayers, intellectuals have laid claim to guide society from the very beginning. But as guardians of hieratic cultures, whether primitive or sophisticated, their moral and ideological innovations were limited by the canons of external authority and by the inheritance of tradition. They were not, and could not be, free spirits, adventurers of the mind.

With the decline of clerical power in the eighteenth century, a new kind of mentor emerged to fill the vacuum and capture the ear of society. The secular intellectual might be deist, sceptic or atheist. But he was just as ready as any pontiff or presbyter to tell mankind how to conduct its affairs. (1)

Rousseau was the first intellectual to proclaim himself, repeatedly, the friend of all mankind. But loving as he did humanity in general, he developed a strong propensity for quarrelling with human beings in particular. (10)

Partly by accident, partly by instinct, partly by deliberate contrivance, [Rousseau] was the first intellectual systematically to exploit the guilt of the privileged. And he did it, moreover, in an entirely new way, by the systematic cult of rudeness. (11)

Since a large part of Rousseau's reputation rests on his theories about the upbringing of children ... it is curious that, in real life as opposed to writing, he took so little interest in children. There is no evidence whatever that he studied children to verify his theories. (21)

The State must form the minds of all, not only as children (as it had done to Rousseau's in the orphanage) but as adult citizens. By a curious chain of infamous moral logic, Rousseau's iniquity as a parent was linked to his ideological offspring, the future totalitarian state. (23)

Though Rousseau writes about the General Will in terms of liberty, it is essentially an authoritarian instrument, an early adumbration of Lenin's 'democratic centralism'. (24)

In a number of ways the State Rousseau planned for Corsica anticipated the one the Pol Pot regime actually tried to create in Cambodia, and this is not entirely surprising since the Paris-educated leaders of the regime had all absorbed Rousseau's ideas. (25)

He did not use the word 'brainwash', but he wrote: 'Those who control a people's opinions control its actions.' Such control is established by treating citizens, from infancy, as children of the State, trained to 'consider themselves only in their relationship to the Body of the State'. 'For being nothing except by it, they will be nothing except for it. It will have all they have and will be all they are.' Again, this anticipates Mussolini's central Fascist doctrine: 'Everything within the State, nothing outside the State, nothing against the State.' The educational process was thus the key to the success of the cultural engineering needed to make the State acceptable and successful; the axis of Rousseau's ideas was the citizen as child and the State as parent, and he insisted the government should have complete charge of the upbringing of all children. Hence-and this is the true revolution Rousseau's ideas brought about--he moved the political process to the very centre of human existence by making the legislator, who is also a pedagogue, into the new Messiah, capable of solving all human problems by creating New Men. (25-6)

Rousseau thus prepared the blueprint for the principal delusions and follies of the twentieth century. Rousseau's reputation during his lifetime, and his influence after his death, raise disturbing questions about human gullibility, and indeed about the human propensity to reject evidence it does not wish to admit. (26)

It is all very baffling and suggests that intellectuals are as unreasonable, illogical and superstitious as anyone else. (27)

Like Rousseau, [Shelley] loved humanity in general but was often cruel to human beings in particular. He burned with a fierce love but it was an abstract flame and the poor mortals who came near it were often scorched. He put ideas before people and his life is a testament to how heartless ideas can be. (31)

[Mary Shelley] had seen the underside of the intellectual life and had felt the power of ideas to hurt. When a friend, watching Percy learning to read, remarked: 'I am sure he will live to be an extraordinary man,' Mary Shelley blazed up: 'I hope to God,' she said passionately, 'he grows up to be an ordinary one.' (51)

Karl Marx has had more impact on actual events, as well minds of men and women, than any other intellectual in modern times. The reason for this is not primarily the attraction of his concepts and methodology, though both have a strong appeal to unrigorous minds, but the fact that his philosophy has been institutionalized in two of the world's largest countries, Russia and China, and their many satellites. (52)

[Marx] was not interested in finding the truth but in proclaiming it. (54)

Marx, in short, is an eschatological writer from start to finish. (55)

Thus far Marx's explanation of what was wrong with the world was a combination of student-café anti-Semitism and Rousseau. He broadened it into his mature philosophy over the next three years, 1844-46, during which he decided that the evil element in society, the agents of the usurious money-power from which he revolted, were not just the Jews but the bourgeois class as a whole. (58)

Some of the sentences I have quoted ... would sound equally plausible or implausible if they were altered to say the opposite. Where, then, were the facts, the evidence from the real world, to turn these prophetic utterances of a moral philosopher, these revelations, into a science? (59)

Marx, then, was unwilling either to investigate working conditions in industry himself or to learn from intelligent working men who had experienced them. Why should he? In all essentials, using the Hegelian dialectic, he had reached his conclusions about the fate of humanity by the late 1840s. All that remained was to find the facts to substantiate them, and these could be garnered from newspaper reports, government blue books and evidence collected by earlier writers; and all this material could be found in libraries. Why look further? The problem, as it appeared to Marx, was to find the right kind of facts: the facts that fitted. His method has been well summarized by the philosopher Karl Jaspers:

The style of Marx's writings is not that of the investigator ... he does not quote examples or adduce facts which run counter to his own theory but only those which clearly support or confirm that which he considers the ultimate truth. The whole approach is one of vindication, not investigation, but it is a vindication of something proclaimed as the perfect truth with the conviction not of the scientist but of the believer.

In this sense, then, the 'facts' are not central to Marx's work; they are ancillary, buttressing conclusions already reached independently of them. (62-3)

Marx brought to the use of primary and secondary written sources the same spirit of gross carelessness, tendentious distortion and downright dishonesty which marked Engels's work. Indeed they were often collaborators in deception, though Marx was the more audacious forger. ... With the object of stirring the English working class from its apathy, and anxious therefore to prove that living standards were falling, he deliberately falsified a sentence from W. E. Gladstone's Budget speech of 1863. ... Marx's misquotation was pointed out. Nonetheless, he reproduced it in Capital, along with other discrepancies, and when the falsification was again noticed and denounced, he let out a huge discharge of obfuscating ink; he, Engels and later his daughter Eleanor were involved in the row, attempting to defend the indefensible, for twenty years. None of them would ever admit the original, clear falsification and the result of the debate is that some readers are left with the impression, as Marx intended, that there are two sides to the controversy. There are not. Marx knew Gladstone never said any such thing and the cheat was deliberate. It was not unique. Marx similarly falsified quotations from Adam Smith. (66-7)

The truth is, even the most superficial inquiry into Marx's use of evidence forces one to treat with scepticism everything he wrote which relies on factual data. He can never be trusted. The whole of the key Chapter Eight of Capital is a deliberate and systematic falsification to prove a thesis which an objective examination of the facts showed was untenable. (67-8)

What emerges from a reading of Capital is Marx's fundamental failure to understand capitalism. He failed precisely because he was unscientific: he would not investigate the facts himself, or use objectively the facts investigated by others. From start to finish, not just Capital but all his work reflects a disregard for truth which at times amounts to contempt. That is the primary reason why Marxism, as a system, cannot produce the results claimed for it; and to call it 'scientific' is preposterous. (69)

Much of Marx's time, in fact, was spent in collecting elaborate dossiers about his political rivals and enemies, which he did not scruple to feed to the police if he thought it would serve his turn. ... there is nothing in the Stalinist epoch which is not distantly prefigured in Marx's behaviour. (71)

That Marx, once established in power, would have been capable of great violence and cruelty seems certain. But of course he was never in a position to carry out large-scale revolution, violent or otherwise, and his pent-up rage therefore passed into his books, which always have a tone of intransigence and extremism. Many passages give the impression that they have actually been written in a state of fury. In due course Lenin, Stalin and Mao Tse-tung practiced, on an enormous scale, the violence which Marx felt in his heart and which his works exude. (71-2)

How could an egoist like Marx inspire such affection? The answer, I think, is that he was strong, masterful, in youth and early manhood handsome, though always dirty; not least, he was funny. Historians pay too little attention to this quality; it often helps to explain an appeal otherwise mysterious (it was one of Hitler's assets, both in private and as a public speaker). Marx's humour was often biting and savage. Nonetheless his excellent jokes made people laugh. Had he been humourless, his many unpleasant characteristics would have denied him a following at all, and his womenfolk would have turned their backs on him. But jokes are the surest way to the hearts of much-tried women, whose lives are even harder than men's. Marx and Jenny were often heard laughing together, and later it was Marx's jokes, more than anything else, which bound his daughters to him. (76)

In contrast to his efforts to portray Anna Karenina, [Tolstoy] never seems to have made any serious attempt in real life to penetrate and understand the mind of a woman. Indeed he would not admit that a woman could be a serious, adult, moral human being. (117)

[Tolstoy] continued to let the peasants, or rather the idea of the peasants--he never saw them as individual human beings--nag at his mind. (122)

It is a curious delusion of intellectuals, from Rousseau onwards, that they can solve the perennial difficulties of human education at a stroke, by setting up a new system. (123)

This desertion, as she saw it, provoked from the Countess a letter which struck a new note of bitterness in their relationship. It sums up not only her own difficulties with Tolstoy but the anger most ordinary people come to feel in coping with a great humanitarian intellectual: 'My little one is still unwell, and I am very tender and pitying. You and Syutayev may not especially love your own children, but we simple mortals are neither able nor wish to distort our feelings or to justify our lack of love for a person by professing some love or other for the whole world.'

Sonya was raising the question, as a result of observing Tolstoy's behaviour over many years, not least to his own family, whether he ever really loved any individual human being, as opposed to loving mankind as an idea. (125)

As with most intellectuals, there came a time in [Tolstoy's] life when he felt the need to identify himself with 'the workers'. (127)

If he had argued, as Dickens, Conrad and other great novelists did, that structural improvements were of only limited value and that what was required were changes in human hearts, he would have made some sense. But Tolstoy, while stressing the need for individual moral improvement, would not let matters rest there: he constantly hinted at the need for, the imminence of, some gigantic moral convulsion, which would turn the world upside down and install a heavenly kingdom. His own utopian efforts were designed to adumbrate this millenarian event. But there was no serious thinking behind this vision. It had something of the purely theatrical quality of the cataclysm which, as we have seen, was the poetic origin of Marx's theory of revolution. (129)

he believed that hidden laws really govern our lives. They are unknown and probably unknowable, and rather than face this disagreeable fact we pretend that history is made by great men and heroes exercising free will. At bottom Tolstoy, like Marx, was a gnostic, rejecting the apparent explanations of how things happen, looking for knowledge of the secret mechanism which lay beneath the surface. This knowledge was intuitively and collectively perceived by corporate groups-the proletariat for Marx, the peasants for Tolstoy. Of course they needed interpreters (like Marx) or prophets (like Tolstoy) but it was essentially their collective strength, their 'rightness', which set the wheels of history in motion. In War and Peace, to prove his theory of how history works, Tolstoy distorted the record, just as Marx juggled his Blue Book authorities and twisted his quotations in Capital.48 He refashioned and made use of the Napoleonic Wars, just as Marx tortured the Industrial Revolution to fit his Procrustean bed of historical determinism.

It is not therefore surprising to find Tolstoy moving towards a collectivist solution to the social problem in Russia. (130)

Tolstoy in celebrated old age set a pattern which (as we shall see) was to recur among leading intellectuals who enjoy world fame: he formed a kind of pseudo-government, taking up 'problems' in various parts of the world, offering solutions, corresponding with kings and presidents, dispatching protests, publishing statements, above all signing things, lending his name to causes, sacred and profane, good and bad. (132)

Visitors, or members of the inner circle, noted down Tolstoy's obiter dicta. They are not impressive. They remind one of Napoleon's Sayings in Exile or Hitler's Table-Talk--eccentric generalizations, truisms, ancient, threadbare prejudices, banalities. (132)

Tolstoy's case is another example of what happens when an intellectual pursues abstract ideas at the expense of people. (137)

Indeed, in so far as Hemingway had literary progenitors, it might be said he was the offspring of a marriage between Kipling and Joyce. ... But Kipling was not an intellectual. He was a genius, he had a 'daemon' but he did not believe he could refashion the world by his own unaided intelligence, he did not reject the vast corpus of its inherited wisdom. On the contrary, he fiercely upheld its laws and customs as unalterable by puny man and depicted with relish the nemesis of those who defied them. (149, 151)

Like many other intellectuals, from Rousseau onwards, [Hemingway] had a striking talent for self-publicity. (153)

True? False? An exaggeration? One does not know. None of Hemingway's statements about himself, and very few he made about other people, can ever be accepted as fact without corroboration. Despite the central importance of truth in his fictional ethic he had the characteristic intellectual's belief that, in his own case, truth must be the willing servant of his ego. (154)

Whether he believed these fantastic notions is hard to say: throughout his life Hemingway was a mixture of superficial sophistication concealing an abyss of credulity on almost any subject. (158)

For a man whose code and whose fiction exalted the virtues of friendships, he found it curiously difficult to sustain any for long. (159)

Why did Hemingway long for death? It is by no means unusual among writers. His contemporary Evelyn Waugh, a writer in English of comparable stature during this period, likewise longed for death. But Waugh was not an intellectual: he did not think he could refashion the rules of life out of his own head but submitted to the traditional discipline of his church, dying of natural causes five years later. Hemingway created his own code, based on honour, truth, loyalty. He failed it on all three counts, and it failed him. (171)

It was the usual tale of intellectual idealism. Ideas came before people, Mankind with a capital 'M' before men and women, wives, sons or daughters. Oscar Homolka's wife Florence, who knew Brecht well in America, summed it up tactfully: 'in his human relationships he was a fighter for people's rights without being overly concerned with the happiness of persons close to him.' Brecht himself argued, quoting Lenin, that one had to be ruthless with individuals to serve the collective. (187)

Adorno said that Brecht spent hours every day putting dirt under his fingernails so he looked like a worker. (188)

One of the reasons why Adorno and his friends disliked Brecht so much was that they resented his identification with 'the workers', which they rightly saw as humbug. Of course their own claim to understand what 'the workers' really wanted, felt and believed was equally without foundation; they led entirely middle-class lives too and, like Marx himself, never met the sons of toil. But at least they did not dress up as proles, in clothes carefully designed by expensive tailors. There was a degree of lying, of systematic deception about Brecht which turned even their stomachs. (188-9)

When Stalin finally died, Brecht's comment was: 'The oppressed of all five continents ... must have felt their heartbeats stop when they heard that Stalin was dead. He was the embodiment of their hopes.' (191)

But other desires of Brecht were carried out. He expressed the wish to be buried in a grey steel coffin, to keep out worms, and to have a steel stiletto put through his heart as soon as he was dead. This was done and published: the news being the first indication to many who knew him that he had a heart at all.

I have striven, in this account, to find something to be said in Brecht's favour. But apart from the fact that he always worked very hard-and sent food parcels to people in Europe during and just after the war (but this may have been Weigel's doing)-there is nothing to be said for him. He is the only intellectual among those I have studied who appears to be without a sole redeeming feature. (195-6)

Like most intellectuals he preferred ideas to people. There was no warmth in any of his relationships. He had no friends in the usual sense of the word. He enjoyed working with people, provided he was in charge. But, as Eric Bentley noted, working with him was a series of committee or board meetings. He was not, Bentley said, interested in people as individuals. This was probably why he could not create characters, only types. He used them as agents for his purposes. (196)

No intellectual in history offered advice to humanity over so long a period as Bertrand Russell, third Earl Russell (1872-1970). He was born in the year General Ulysses S. Grant was reelected to the US Presidency and he died on the eve of Watergate. He was a few months younger than Marcel Proust and Stephen Crane, a few weeks older than Calvin Coolidge and Max Beerbohm; yet he lived long enough to salute the revolting students of 1968 and enjoy the work of Stoppard and Pinter. All this time he put forth a steady stream of counsel, exhortation, information and warnings on an astonishing variety of subjects. (197)

Why did Russell feel qualified to offer so much advice, and why did people listen to him? (197-8)

Certainly, Russell was not a man who ever acquired extensive experience of the lives most people lead or who took much interest in the views and feelings of the multitude. (198)

In fact the notion of Russell carrying philosophy into the world is quite misleading; rather he tried, unsuccessfully, to squeeze the world into philosophy and found it would not fit. (201)

[N]o one was more detached from physical reality than Russell. He could not work the simplest mechanical device or perform any of the routine tasks which even the most pampered man does without thinking. He loved tea but could not make it. When his third wife, Peter, had to go away and wrote down on the kitchen slate: 'Lift up bolster of the Esse [cooker]. Move kettle onto hot-plate. Wait for it to boil. Pour water from kettle onto teapot,' he failed dismally to carry out this operation. (202)

This angry passage betrays such deep ignorance of how ordinary people's emotions function in wartime, or indeed at any other time, as almost to defy comment. There are many other statements in his volumes of autobiography which produce a sense of wonder in the normal reader that so clever a man could be so blind to human nature. (202)

Russell may have hated war but there were times when he loved force. There was something aggressive, even bellicose, about his pacifism. (204)

The great editor under whom I served, Kingsley Martin, who knew Russell well, often used to say that all the most pugnacious people he had come across were pacifists, and instanced Russell. Russell's pupil T.S. Eliot said the same: '[Russell] considered any excuse good enough for homicide.' It was not that Russell had any taste for fisticuffs. But he was in some ways an absolutist who believed in total solutions. He returned more than once to the notion of an era of perpetual peace being imposed on the world by an initial act of forceful statesmanship. (204)

He regarded Stalin as a monster and accepted as true the fragmentary accounts of the forced collectivization, the great famine, the purges and the camps which reached the West. In all these ways he was quite untypical of the progressive intelligentsia. Nor did he share the complacency with which, in 1944-45, they accepted the extension of Soviet rule to most of Eastern Europe. To Russell this was a catastrophe for Western civilization. (205)

History shows that all pacifist movements reach a point at which the more militant element becomes frustrated at the lack of progress and resorts to civil disobedience and acts of violence. (209)

Many of Russell's sayings, from 1960 on, were not merely fervent but outrageous and were often made on the spur of the moment, when he had worked himself up into a state of righteous indignation with those who did not share his views. Thus, for a speech in Birmingham in April 1961, he had prepared notes which read:

'On a purely statistical basis, Macmillan and Kennedy are about fifty times as wicked as Hitler.' This was bad enough since (apart from anything else) it was comparing historical fact with futurist projection. But a recording shows that what Russell actually went on to say in his speech was: 'We used to think Hitler was wicked when he wanted to kill all the Jews. But Kennedy and Macmillan not only want to kill all the Jews but all the rest of us too. They're much more wicked than Hitler.' He added: 'I will not pretend to obey a government which is organizing the massacre of the whole of mankind--They are the wickedest people that ever lived in the history of man.' (209-10)

What Russell omitted to state was that there had been certain activities on his own part and, contrary to his policy of openness, they had been furtive. Indeed it is a significant fact that, in every case where intellectuals try to apply total disclosure to sex, it always leads in the end to a degree of guilty secrecy unusual even in normally adulterous families. (216)

As with so many famous intellectuals, people--and that included children and wives-tended to become servants of his ideas, and therefore in practice of his ego. (219)

If many of the statements put out under his name seem childish today, it must be remembered that the 1960s was a childish decade and Russell one of its representative spirits. (221)

The ability to get the best of both worlds, the world of progressive self-righteousness and the world of privilege, is a theme which runs through the lives of many leading intellectuals, and none more so than Bertrand Russell's. (223)

As Sartre had little respect for the truth it is difficult to say how much credence should be placed on his description of his childhood and youth. (226)

The quarrel with Camus was as bitter as Rousseau's rows with Diderot, Voltaire and Hume, or Tolstoy's with Turgenev-and, unlike the last case, there was no reconciliation. Sartre seems to have been jealous of Camus' good looks, which made him immensely attractive to women, and his sheer power and originality as a novelist: La Peste, published in June 1947, had a mesmeric effect on the young and rapidly sold 350,000 copies. This was made the object of some ideological criticism in Les Temps modernes but the friendship continued in an uneasy fashion. As Sartre moved towards the left, however, Camus became more of an independent. In a sense he occupied the same position as George Orwell in Britain: he set himself against all authoritarian systems and came to see Stalin as an evil man on the same plane as Hitler, Like Orwell and unlike Sartre he consistently held that people were more important than ideas. De Beauvoir reports that in 1946 he confided in her: 'What we have in common, you and I, is that individuals count most of all for us. We prefer the concrete to the abstract, people to doctrines. We place friendship above politics.'

In her heart of hearts de Beauvoir may have agreed with him, but when the final break came, over Camus' book L'Homme révolté [[LINK]] in 1951-52, she of course sided with Sartre's camp, He and his acolytes at Les Temps modernes saw the book as an assault on Stalinism and decided to go for it in two stages. (240-41)

The trouble with Sartre is that he did not know, and made no effort to meet, any workers. (241)

David Rousset, found him quite useless: 'despite his lucidity, he lived in a world which was totally isolated from reality.' He was, said Rousset, 'very much involved in the play and movement of ideas' but took little interest in actual events: 'Sartre lived in a bubble.' (242)

Since Sartre's writings were very widely disseminated, especially among the young, he thus became the academic godfather to many terrorist movements which began to oppress society from the late 1960s onwards. What he did not foresee, and what a wiser man would have foreseen, was that most of the violence to which he gave philosophical encouragement would be inflicted by blacks not on whites but on other blacks. By helping Fanon to inflame Africa, he contributed to the civil wars and mass murders which have engulfed most of that continent from the mid-1960s onwards to this day. His influence on South-East Asia, where the Vietnam War was drawing to a close, was even more baneful. The hideous crimes committed in Cambodia from April 1975 onwards, which involved the deaths of between a fifth and a third of the population, were organized by a group of Francophone middle-class intellectuals known as the Angka Leu ('the Higher Organization'). Of its eight leaders, five were teachers, one a university professor, one a civil servant and one an economist. All had studied in France in the 1950s, where they had not only belonged to the Communist Party but had absorbed Sartre's doctrines of philosophical activism and 'necessary violence'. These mass murderers were his ideological children. (246)

Sartre's efforts do not appear to have aroused even a flicker of interest among the actual car workers; all his associates were middle-class intellectuals, as they always had been. (248)

Indeed Sartre, like Russell, failed to achieve any kind of coherence and consistency in his views of public policy. No body of doctrine survived him. In the end, again like Russell, he stood for nothing more than a vague desire to belong to the left and the camp of youth. (251)

But [Edmund] Wilson, having a genuine passion for truth, and unlike virtually all the intellectuals described in this book, did make a serious, sincere and prolonged effort to brief himself on the social conditions about which he wished to pontificate. ... he determined to explore communism not only in its theoretical origins-he was already working on what was to become a major account of Marxist history, To the Finland Station-but in its practical applications in the Soviet Union. In certain ways he made a bigger effort to get at the truth than any other intellectual of the 1930s. He learned to read and speak Russian. He mastered much of its literature in the original. (256)

Clearly it was Wilson's irrepressible interest in people, his unwillingness to allow them to be effaced by ideas, which prevented him from sustaining the posture of the intellectual for long. By the end of the 1930s all the instincts and itches of the man of letters were returning. But the process of emancipating himself from the lure of Marxism and the left was not easy. To the Finland Station grew and grew. It was not finally published till 1940, and not until the second edition did Wilson denounce Stalinism as 'one of the most hideous tyrannies the world has ever known'. (258)

Wilson is not in the least distressed by the sufferings which Marx, in the cause of his 'art-science', inflicted on his family; he can imagine doing it himself, at any rate in theory. But in practice? Wilson clearly lacked the disregard for truth and the preference for ideas over people which marks the true secular intellectual. (258)

There was also a lack of balance about ordinary affairs of the world which we come across time and again in the ranks of the intellectuals and which lingered on in Wilson long after he broke from them. It emerged suddenly and disastrously in Wilson's embittered battle with the officials of the American Internal Revenue Service, about which he wrote an indignant book. His problem was quite simple: between 1946 and 1955 he did not file any income-tax returns, a serious offence in the United States as in most other countries. Indeed in America it is normally so heavily punished, by fines and jail, that when Wilson first confessed his delinquency to a lawyer he 'told me at once that I was evidently in such a mess that the best thing I could do was to become a citizen of some other country'. ... [I]n 1955 when the New Yorker published his long and much admired study of the Dead Sea Scrolls, which was made into a successful book. It was then that he went to the tax lawyer, whose advice came as a shock: 'I had no idea at that time of how heavy our taxation had become or of the severity of the penalties for not filing tax returns.'

This was an extraordinary admission. Here was a man who had written extensively on social, economic and political problems throughout the 1930s and who had offered vehement advice to the authorities involving heavy public expenditures and the nationalization of major industries. He had also published a large book, To the Finland Station, tracing with enthusiasm the development of ideas designed to revolutionize the position of ordinary people by seizing the assets of the bourgeoisie. How did he think the state paid its way during the high-spending New Deal, of which he strongly approved? Did he not feel it the personal responsibility of all to make such reforms work, especially those, like himself, who had expressed direct moral obligations towards the less-favoured? What about the Marxist tag, which he endorsed: 'From each according to his ability, to each according to his need'? Or did he think that applied to others but not to himself? Was this a case, in short, of a radical who favoured humanity in general but did not think of human beings in particular? If so, he was in good, or rather bad, company, since Marx seems never to have paid one penny of income tax in his life. Wilson's attitude was in fact a striking' example of the intellectual who, while telling the world how to run its business, in tones of considerable moral authority, thinks the practical consequences of such advice have nothing to do with those like himself-they are for 'ordinary people'. (266-7)

the IRS in the end let him off with a compromise settlement of $25,000. So he should have considered himself lucky. Instead Wilson wrote his diatribe, The Cold War and the Income Tax: a Protest. This was in every way an irrational response to his troubles. They had given him a frightening insight into the harshness of the modern state at its most belligerent-the tax-gathering role-but this should have come as no surprise to an imaginative man who had made it his business to study the state in theory and in practice. The person who is in the weakest moral position to attack the state is he who has largely ignored its potential for evil while strongly backing its expansion on humanitarian grounds and is only stirred to protest when he falls foul of it through his own negligence. That exactly describes Wilson's position. (267)

In short, the book shows Wilson at his worst and makes one grateful that, in general, he ceased being a political intellectual by the time he was forty. (267)

These books, and other works, were characterized by courage as well as industry-writing on the Scrolls involved learning Hebrew-and by an undeviating and relentless concern for truth. That in itself set him apart from most intellectuals. But still more so did the way in which Wilson's research and writings centred around a strong, warm, penetrating and civilized concern for people, both as groups and individuals, rather than abstract ideas. (268)

The cruelty of ideas lies in the assumption that human beings can be bent to fit them. (268)

It was Wilson's humanism ... which saved him from the millenarian fallacy. (268)

One thing which emerges strongly from any case-by-case study of intellectuals is their scant regard for veracity. Anxious as they are to promote the redeeming, transcending Truth, the establishment of which they see as their mission on behalf of humanity, they have not much patience with the mundane, everyday truths represented by objective facts which get in the way of their arguments. These awkward, minor truths get brushed aside, doctored, reversed or are even deliberately suppressed. The outstanding example of this tendency is Marx. But all those we have looked at suffered from it to some extent, the only exception being Edmund Wilson, who perhaps was not a true intellectual at all. Now come two intellectuals in whose work and lives deception--including self-deception--played a central, indeed determining role. (269)

[Victor Gollancz] was in no sense an evil man and even when he did wrong he was usually aware of it and his conscience pricked him. But his career shows strikingly the extent to which deception plays a part in the promotion of millenarian ideas. (269)

Even in his lifetime, people who had dealings with him were aware how cavalier he could be with the truth. But now, thanks to the honesty of his daughter, Livia Gollancz, who opened his papers for inspection, and the skilful fair-mindedness of a first-class biographer, Ruth Dudley Edwards, the exact nature and extent of his deceits can be examined. (269)

This was to be the watchword of his life: he was a seer, a magus, who had got hold of a Truth, or The Truth, and was determined to pound it into the heads of others. (271)

He believed he had a perfect memory. What he had, rather, was an astonishing capacity to rewrite history in his head and then defend the new version with passionate conviction. (273)

To an agent who tried to challenge his memory he wrote: 'How dare you! I am incapable of error.' (273)

Gollancz's self-deceptions inflicted suffering on himself as well as others. But clearly a man whose grasp of objective reality was so weak in some ways was not naturally suited to give political advice to humanity. He was a socialist of one kind or another all his life, which he believed was devoted to helping 'the workers'. He was convinced he knew what 'the workers' thought and wanted. But there is no evidence that he ever knew a single working-class man, unless one counts the British Communist Party boss, Harry Pollitt, who had once been a boiler-maker. (276)

There is no evidence he ever denied himself anything he wanted. (276)

It is a curious fact that Gollancz's participation in the active anti-capitalist cause dates from 1928-30, just at the time when he was becoming a highly successful capitalist himself. He argued that it encouraged man's natural propensity to greed and so to violence. By September 1939 we find him writing to the playwright Benn Levy that Marx's Capital was 'in my view the fourth most enthralling volume in the world's literature'; it combined 'the attractions of an A-plus detective story and a gospel' (can he actually have read it?). This was the prelude to a long love-affair with the Soviet Union. He swallowed whole the Webbs' fantastic account of how the Soviet system functioned. He described it as 'amazingly fascinating'; the chapters designed to eliminate 'misconceptions' about the democratic nature of the regime were 'much the most important in the book'.15 In due course-at the height of the great purges, as it happens-he nominated Stalin 'Man of the Year'. (276)

What in effect Gollancz was saying, as his letters at this time constantly suggest, was that he wanted slanted books but books which did not appear slanted. These letters which have survived in the Gollancz files are peculiarly fascinating because they constitute one of the few occasions when direct evidence can be produced of an intellectual poisoning the wells of truth, knowing he was doing wrong and justifying his actions by claiming a higher cause than truth itself. (278)

He also launched huge ventures designed primarily to promote socialism and the image of the Soviet Union. The first was the New Soviet Library, a series of propaganda books by Soviet authors arranged directly through the Soviet Embassy and government. But unforeseen difficulties occurred in getting hold of the texts, since the gestation of the series coincided with the great purges. Several of the proposed authors abruptly disappeared into the Gulag archipelago or were hauled in front of firing squads. Some of the texts were sent to Gollancz with the name of the author blank, to be filled in later when the executed writer had been officially replaced. A further, and gruesome, setback was that Andrei Vishinsky, the Soviet public prosecutor, who played the same part in Stalin's regime as Roland Freisler, chairman of the People's Court, in Hitler's, was down to contribute the volume on Soviet Justice; but he was too busy getting death sentences passed on former comrades to write it. When the text finally arrived, it was too hastily and badly written to be published. Gollancz's readers were kept blissfully unaware of these problems. (279)

He was haunted by Orwell's honesty-as indeed was Kingsley Martin-for the rest of his life, and driven, in exasperation, to attacks on him which do not make much ethical, or indeed any other, sense. He could not accept, he wrote, 'that [Orwell's] intellectual honesty was impeccable ... in my opinion he was too desperately anxious to be honest to be really honest.' (285)

In 1946, when the ship on which he was taking a holiday docked in the Canary Isles, he had a sudden bout of the terrors and shouted that Franco's police intended to seize and torture him as soon as he landed. He insisted the British consul come on board to protect him. The consul sent his clerk to assure him that nobody on the islands had ever heard of him; indeed, a disappointed Gollancz reported, 'he had never heard of me himself'. (286)

If Victor Gollancz was an intellectual who tampered with the truth in the interests of his millenarian aims, Lillian Hellman seems to have been one to whom falsehood came naturally. Like Gollancz she was part of that great intellectual conspiracy in the West to conceal the horrors of Stalinism. Unlike him, she never admitted her errors and lies, except in the most perfunctory and insincere fashion; indeed she went on to pursue a career of even more flagrant and audacious mendacity. (288)

[D]uring the last decades of her life, and partly in consequence of her deceptions, she achieved a position of prestige and power in the American intellectual scene which has seldom been equalled. Indeed the Hellman case raises an important general question: to what extent do intellectuals as a class expect and require truth from those they admire? (288)

The quarrel between Hellman and Bankhead was really about who was on the side of 'the workers'. The truth is that neither knew anything about the working class beyond occasionally taking a lover from its ranks. (296)

[S]he shared with Hammett another habit-a failure to pay income tax. As the cases of Sartre and Edmund Wilson suggest, there is a common propensity among radical intellectuals to demand ambitious government programmes while feeling no responsibility to contribute to them. (300)

[I]ntellectual heroes, or heroines, are not disposed of so easily. Just as south Italian peasants continue to make offerings and present petitions to their favourite saints long after their very existence has been exposed as an invention, so the lovers of progress too cling to their idols, feet of clay notwithstanding. Though Rousseau's monstrous behaviour was well known even in his own lifetime, the reason-worshippers flocked to his shrine and institutionalized the myth of his goodness. No revelations about Marx's private conduct or his public dishonesty, however well-documented, seem to have disturbed the faith of his followers in his righteousness. Sartre's long decline and the unrelieved fatuity of his later views did not prevent 50,000 Parisian cognoscenti turning out for his obsequies. Hellman's funeral, in Martha's Vineyard, was also well attended. (305)

Orwell had always put experience before theory, and these events proved how right he had been. Theory taught that the left, when exercising power, would behave justly and respect truth. Experience showed him that the left was capable of a degree of injustice and cruelty of a kind hitherto almost unknown, rivalled only by the monstrous crimes of the German Nazis, and that it would eagerly suppress truth in the cause of the higher truth it upheld. (309)

[Waugh] began to correspond with Orwell and visited him in hospital; had Orwell lived, their friendship might well have blossomed. They first came together over a common desire that P.G. Wodehouse, a writer they admired, should not be persecuted for his foolish (but, compared with Ezra Pound's, quite innocuous) wartime broadcasts. This was a case where both men insisted that an individual person must take precedence over the abstract concept of ideological justice. (310)

It is a curious fact that violence has always exercised a strong appeal to some intellectuals. It goes hand in hand with the desire for radical, absolutist solutions. ... The association of intellectuals with violence occurs too often to be dismissed as an aberration. Often it takes the form of admiring those 'men of action' who practise violence. Mussolini had an astonishing number of intellectual followers, by no means all of them Italian. In his ascent to power, Hitler consistently was most successful on the campus, his electoral appeal to students regularly outstripping his performance among the population as a whole. He always performed well among teachers and university professors. Many intellectuals were drawn into the higher echelons of the Nazi Party and participated in the more gruesome excesses of the SS. Thus the four Einsatzgruppen or mobile killing battalions which were the spearhead of Hitler's 'final solution' in Eastern Europe contained an unusually high proportion of university graduates among the officers. Otto Ohlendorf, who commanded 'D' Battalion, for instance, had degrees from three universities and a doctorate in jurisprudence. Stalin, too, had legions of intellectual admirers in his time, as did such post-war men of violence as Castro, Nasser and Mao Tse-tung. (319)

Kingsley Martin, who served in the Quaker Ambulance Unit in the First World War and shrank from actual violence in any shape, sometime muddled himself into defending it theoretically. In 1952, applauding the final triumph of Mao in China, but nervous about reports that one and a half million 'enemies of the people' had been disposed of, he asked foolishly in his New Statesman column: 'Were these executions really necessary?' Leonard Woolf, a director of the journal, forced him to publish a letter the following week in which he asked the pointed question: would Martin 'give some indication ... under what circumstances the execution of 1.5 million persons by a government is "really necessary"?' Martin, of course, could give no answer and his wriggling efforts to get off the hook on which he had impaled himself were painful to behold. (319-20)

It is further evidence of the curious paradox that intellectuals, who ought to teach men and women to trust their reason, usually encourage them to follow their emotions; and, instead of urging debate and reconciliation on humanity, all too often spur it towards the arbitration of force. (333)

It reinforced the message of Frantz Fanon's frenzied polemic, Les Damnés de la terre, and Sartre's rhetoric, that violence was the legitimate right of those who could be defined, by race, class or predicament, to be the victims of moral iniquity.

Now here we come to the great crux of the intellectual life: the attitude to violence. It is the fence at which most secular intellectuals, be they pacifist or not, stumble and fall into inconsistency-or, indeed, into sheer incoherence. They may renounce it in theory, as indeed in logic they must since it is the antithesis of rational methods of solving problems. But in practice they find themselves from time to time endorsing it-what might be called the Necessary Murder Syndrome-or approving its use by those with whom they sympathize. Other intellectuals, confronted with the fact of violence practised by those they wish to defend, simply transfer the moral responsibility, by ingenious argument, to others whom they wish to attack. (337)

Chomsky's argument from innate structures, if valid, might fairly be said to constitute a general case against social engineering of any kind. And indeed, for a variety of reasons, social engineering has been the salient delusion and the greatest curse of the modern age. In the twentieth century it has killed scores of millions of innocent people, in Soviet Russia, Nazi Germany, Communist China and elsewhere. But it is the last thing which Western democracies, with all their faults, have ever espoused. On the contrary. Social engineering is the creation of millenarian intellectuals who believe they can refashion the universe by the light of their unaided reason. It is the birthright of the totalitarian tradition. It was pioneered by Rousseau, systematized by Marx and institutionalized by Lenin. Lenin's successors have conducted, over more than seventy years, the longest experiment in social engineering in history, whose lack of success does indeed confirm Chomsky's general case. Social engineering, or the Cultural Revolution as it was called, produced millions of corpses in Mao's China, and with equal failure. Though applied by illiberal or totalitarian governments, all schemes of social engineering have been originally the work of intellectuals. Apartheid, for instance, was worked out in its detailed, modern form in the social psychology department of Stellenbosch University. (340)

When the American forces withdrew, the social engineers promptly moved in, as those who supported American intervention had all along predicted they would. It was then that the unspeakable cruelties began in earnest. Indeed in Cambodia, as a direct result of American withdrawal, one of the greatest crimes, in a century of spectacular crimes, took place in 1975. A group of Marxist intellectuals, educated in Sartre's Paris but now in charge of a formidable army, conducted an experiment in social engineering ruthless even by the standards of Stalin or Mao.

Chomsky's reaction to this atrocity is instructive. It was complex and contorted. It involved the extrusion of much obfuscating ink. Indeed it bore a striking resemblance to the reactions of Marx, Engels and their followers to the exposure of Marx's deliberate misquotation of Gladstone's Budget speech. It would take too long to examine in detail but the essence was quite simple. America was, by Chomsky's definition, which by now had achieved the status of a metaphysical fact, the villain in Indo-China. Hence the Cambodian massacres could not be acknowledged to have taken place at all until ways had been found to show that the United States was, directly or indirectly, responsible for them. (340-1)

There seems to be, in the life of many millenarian intellectuals, a sinister climacteric, a cerebral menopause, which might be termed the Flight of Reason. (341)

We are now at the end of our enquiry. It is just about two hundred years since the secular intellectuals began to replace the old clerisy as the guides and mentors of mankind. We have looked at a number of individual cases of those who sought to counsel humanity. We have examined their moral and judgmental qualifications for this task. In particular, we have examined their attitude to truth, the way in which they seek for and evaluate evidence, their response not just to humanity in general but to human beings in particular; the way they treat their friends, colleagues, servants and above all their own families. We have touched on the social and political consequences of following their advice.

What conclusions should be drawn? Readers will judge for themselves. But I think I detect today a certain public scepticism when intellectuals stand up to preach to us, a growing tendency among ordinary people to dispute the right of academics, writers and philosophers, eminent though they may be, to tell us how to behave and conduct our affairs. The belief seems to be spreading that intellectuals are no wiser as mentors, or worthier as exemplars, than the witch doctors or priests of old. I share that scepticism. A dozen people picked at random on the street are at least as likely to offer sensible views on moral and political matters as a cross-section of the intelligentsia. But I would go further. One of the principal lessons of our tragic century, which has seen so many millions of innocent lives sacrificed in schemes to improve the lot of humanity, is-beware intellectuals. Not merely should they be kept well away from the levers of power, they should also be objects of particular suspicion when they seek to offer collective advice. Beware committees, conferences and leagues of intellectuals. Distrust public statements issued from their serried ranks. Discount their verdicts on political leaders and important events. For intellectuals, far from being highly individualistic and non-conformist people, follow certain regular patterns of behaviour. Taken as a group, they are often ultra-conformist within the circles formed by those whose approval they seek and value. That is what makes them, en masse, so dangerous, for it enables them to create climates of opinion and prevailing orthodoxies, which themselves often generate irrational and destructive courses of action. Above all, we must at all times remember what intellectuals habitually forget: that people matter more than concepts and must come first. The worst of all despotisms is the heartless tyranny of ideas. (342)

|