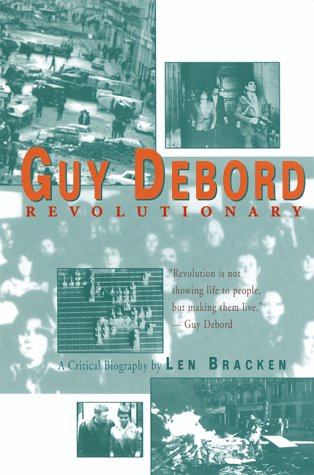

Guy Debord: Revolutionary

Len Bracken (1997)

Despite his attention-getting derision of authority and other avant-gardes, Debord eschewed celebrity status and remained in the margins. In what is almost unimaginable in these days of shameless self-promotion, Debord indulged his creative impulses, but he did so in ways calculated to combat the fame he garnered during the events of Paris in May 1968. (vi-vii)

The masks of gravity and discretion, borrowed from those he considered to be masters, such as Baltasar Gracián, enhanced Debord's reputation for genius in letters. Debord explicitly states that he wanted to give the impression of possessing great talents, which he withheld from his contemporaries. (vii-viii)

The high level of American cultural saturation is seen early on by parodies in French films and novels, featuring characters who spoke to each other in the language of advertisements. Today, this language is so pervasive that parody is virtually impossible. As Debord later put it, "Reality rises up in the spectacle, and the spectacle is real." (8)

[Isidore] Isou created two new class categories: the internes who have a place in the circuit of production like spokes on a wheel; and the externes who refuse to accept the roles available to them and spend their energy in more glorious ways. (10)

The last line of the film, "Nous vivons en enfants perdus nos adventures incompletes," (the line that precedes twenty-four minutes of darkness) could be translated literally as "We live as lost children our incomplete adventures." (20)

Debord's first wife, Michele Bernstein, describes the scene: [...] "I was to make greater noise. And I did. I can't remember if Guy and I even stayed to the finish—you know the last twenty minutes are silence, nothing. But I do know that Serge Berna tried to keep people from leaving. "Don't go!" he said. "At the end there's something really dirty!" (20-1)

[I]t was in 1953 that Debord made his celebrated NEVER WORK inscription in chalk on a wall on Rue de Seine. A photographer stopped to get a shot for a humorous postcard, but Debord wasn't kidding, and later called it, "the most important trace ever revealed on the site of Saint-Germain-des-Pres, as testimony of a particular lifestyle that attempted to affirm itself there." (26)

Chtcheglov's seminal "Formulary For A New Urbanism" follows this call to "explore Paris" by expressing the desperation and hazards of this sort of adventure:

"...stranded in the Red Cellars of Pali-Kao, without music, without geography, no longer setting off for the hacienda where the roots think of the child and where the wine is finished off with fables from an old almanac. Now that's finished. You'll never see the hacienda. It doesn't exist. The hacienda must be built."

As a testament to the power of these words, a "Hacienda" was built as a nightclub in Manchester, England by punk/pop impresario Tony Wilson. (33)

The crucial 1952-1953 period of Debord's life is best presented in Memoires, a work that was not published until 1959. What are Memoires? They are pages comprised of plates of phrases, photos, drawings and cartoons that Debord cut out of other works, and then pasted up in a randomly suggestive manner. Debord then had his comrade and friend, the Danish artist Asger Jorn (1914-1973), taint these "prefabricated elements" with paint. The colors suggest possible readings of the phrases or simply lend a mood to the images. These plates were then bound in sandpaper to destroy any other books it came into contact with—Debord calls them an anti-book. (34; cp. The Feederz album "EVER FEEL LIKE KILLING YOUR BOSS")

It must be stated here that Debord was very conscious of the historical antecedents of the quest of a millenarian utopia, such as the heretical sects of the middle ages, and while he may have mimicked aspects of their efforts to punch a hole in history with a social revolution, he took great pains to highlight the mystical flaws of these movements. (41; cp. Norman Cohn's masterful Pursuit of the Millenium --DoC)

What were the real questions? Leisure. Work. Adventure, and the construction of situations in a permanent free play of passion. The L.I. [Lettrist International] pursued their quest for this Grail by drifting around Paris, building castles of adventure in their minds and recording their thoughts for Potlatch. (46)

The L.I. was an experimental form of collective existence that valued its use of time above all else.*

* The group funded itself by episodically accepting a long list of jobs: "translator, hairdresser, telephone operator, statistician, knitter, receptionist, boxer, free-lance writer, real estate agent, dishwasher, salesperson, letter carrier, African game hunter, typist, cinematographer, tutor, unskilled laborer, secretary, butcher, bartender, sardine packer." (48; 48n)

For the most part, Debord and the L.I. "intensively pursued their psychogeographic research" in the streets. Their "Project for Rational Embellishments of the City of Paris" (diverting the Surrealists' "irrational embellishments") called for opening the metro all night and connecting the rooftops with bridges and opening them for strolls. Regarding the treatment of churches, Debord was for "the total destruction of religious buildings of all faiths." The group was against cemeteries and all traces of cadavers. They didn't care much for museums—the artistic masterpieces could just as well be hung in bars. They thought it would be a good idea to have free access to prisons, so that tourists could visit them. And the L.I. wanted all the monuments and dirty street names removed from the city. In the middle of what is sometimes referred to as the second French Revolution (the inundation of washing machines, the doubling of electric use, the explosion of cheap suburban housing, etc.) these Lettrist embellishments were rational attacks on the past and prsent—imbued with revolutionary passion. (49)

...as [Alexander] Trocchi wrote in Cain's Book: "What's not beside the point is false." Some of the legends are simply incredible, such as using a false collar and portable pulpit to escape drug raids, shooting up on television, and the All Points Bulletin for him in the U.S. on drug charges, which he avoided by stealing two of Plimpton's suits to disguise his escape to England. Readers of Scott's biography are certain to be entertained by these legends. But the legend of Trocchi as a source of artistic inspiration to many young people involved in the Venice Beach beat scene (among them Jim Morrison) is more important. Trocchi's life, however pathetic it seemed to [Greil] Marcus, continues to inspire. And as we have seen, Trocchi had first been inspired by Debord. (59n)

In the French revolution known as the Fronde (1648-1652) [Cardinal de] Retz, or "Gondi" as he is referred to by the L.I., suffered one glorious defeat after another. But the anonymous author of the Potlatch article claims that "The extraordinarily playful value of the life of Gondi, and of this Fronde of which he was the most remarkable inventor, remains to be analyzed from a truly modern perspective."

This isn't the place for such an analysis, but an understanding of the Fronde and Gondi's role in it are important because Debord would later call himself "Gondi."

The word fronde means sling or slingshot—Orest Ranum explains the full connotation of the word in his work on The Fronde: "Picked up by street singers and writers of doggerel, the word fronde became a shorthand way to evolke the congeries of disorderly, illegal, and violent activities. Allusions to the fronde often center on the idea of a collective prank or an adolescent game that could turn sour, become violent, and even take the lives of some of the participants." (60)

What began with delinquents slinging mud at the passing carriages of nobles and breaking carriage house windows with slingshots progressed to a judges strike—they completely stopped prosecuting cases and addressed protests to the crown instead. Eventually other royal officials, such as the treasurers, and some princes and their clients got into the act. Taxes had tripled in the years prior to 1648, and people just couldn't and didn't pay the snakes who had purchased the right to be tax collectors. Priests like Cardinal Retz passed out alms to the poor and published inflammatory pamphlets to put a spin on events. The lesson that Ranum draws from this is that revolutions can be effected by those who already have power. (61)

The "Toward a Situationist International" section of Debord's Report reads like a manifesto. In order to construct situations, both the material environment and human behavior need to be transformed and supercharged by playing games that quantitatively increase human life. Debord envisioned the creation of a "Situationist city" by diverting existing architecture, urban planning, cinema, etc. [...] The acoustic and atmospheric environment would continually be put to experimental use as Situationists playfully intervene in their urban milieu. Those who would want to take up situationist struggles should note that while these games were, and still are, radical in regard to societal norms, Debord explicitly makes the point that they entail a highly moralistic revolution in mores. (75)

In a much earlier work, unknown to Lefebvre, Lukacs had established the opposition between the mechanical, dreary repetition of everyday life of "trivial life" and "authentic life," when a being creates or becomes a work of art. In his major work, History and Class Consciousness, Lukacs discarded this formulation in favor of locating consciousness in historicity and finding alienation in "reification of consciousness." Michele Bernstein, in her first-person novel Tous les chevaux du roi (dedicated to "Guy") plays with this concept by having the "other woman" ask Debord's character Gilles about his profession.

Carol: "What do you do?"

"Reification," answered Gilles.

"It's a serious study," I added.

"Yes," he said.

"I see," observed Carole with admiration. "It's very serious work with big books and lots of papers on a large table."

"No," Gilles said. "I drift. Principally, I drift." (91-2)

Atkins went on to explain that the first (and only) question, a general question about "Situationism" received the following response: "Guy Debord stood up and said in French `We're not here to answer cuntish questions.' At this he and the other Situationists walked out." (100)

It was in December, 1967 that Vaneigem's The Revolution of Everyday Life was published by Gallimard. This Treatise on How to Live, as a literal translation of the French title reads, has done more to spread sabotage and subversion as any book I know. (157)

[C]onsider the cynical diversion of an infamous critique of Schiller's Die Rauber that Debord used as preview of the film Society of the Spectacle—scrolled white letters on a black background:

When the idea occurred to me to create the world, I foresaw that there, one day, someone would make a film as revolting as Society of the Spectacle. Therefore, I thought it better not to create the world (signed): God (189)

Rather than using the standard "le fin" to end his film, Debord used the subtitle: "To be begun again from the beginning." The note on this states that the film is worth being seen again to "achieve more fully its despairing effect." (202)

The 1989 incident involved a Times of London story that claimed that the Village Voice had run a story about Debord's ties to the C.I.A.—the problem was that the Village Voice never ran such a story. My FOIA request to get the C.I.A. file on Debord was turned down on the grounds they could "neither confirm or deny" the existence of such a file. (214)

Debord had a deep disgust for the way masters ruled their ignorant servants, and he felt free to hail resistance to domination as a Renaissance-style virtue. The revolutionary perspective was the only logical and mentally healthy perspective for Debord, although he would, like Nietzsche, freely admit that he was decadent.

The "servitude" created by this generalized decadence echoes Etienne de La Boetie's celebrated Discourse on Voluntary Servitude (1577), a text sprinkled with classical examples and more contemporaneous historical examples that drew on the experience of Huguenot Protestants in XVIth Century France, such as the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre of Calvinists in Paris by Catholics in 1572. La Boetie's arguments are worth recalling here, especially the central argument that people tend to enslave themselves, and that tyrants fall, not from violent action, but when the people withdraw their support. Even among those raised in subjection, La Boetie contends, even among those trained to adore rulers, there will always be those who refuse to submit because liberty is the natural condition of the people. For La Boetie, change is dependent on the negation of the vast networks of corrupted people who have an interest in maintaining tyranny: "When they lose their liberty through deceit they are not so often betrayed by others as misled by themselves."

Debord's Comments echoes La Boetie as it traces the base of generalized decadence to the ignorance of spectators who put up with everything from art frauds to pollution to the entire commodity-driven logic of the spectacle. Conflicts and scandals come and go without much notice: "Secrecy dominates the world, foremost as the secret of domination." (224-5)

I'd like to note here that while Debord enjoyed some rock 'n' roll and jazz, his strongest taste in music was for classical French composers such as Michel Corrette, Francois Couperin, Delalande, etc. I mention this because of the way the S.I. has been associated with punk following the publication of Greil Marcus' Lipstick Traces in 1989. It's worth recalling that even Marcus came around to the conclusion that there's nothing revolutionary about punk nightclub acts. (233)

|