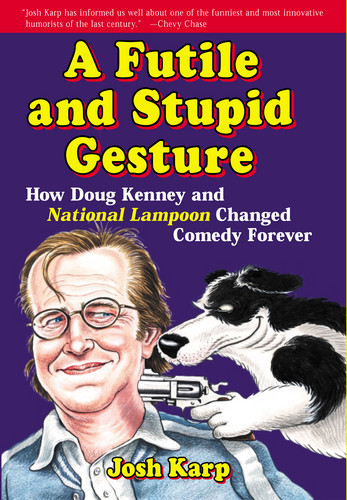

A Futile and Stupid Gesture: How Doug Kenney and National Lampoon Changed Comedy Forever

Josh Karp (2006)

[From the acknowledgements:] P. J. O'Rourke stands out for his thoughtfulness and candor in a situation where he had little to gain from his participation. With maturity and self-knowledge, he viewed the world of National Lampoon in the 1970s with as much objectivity as possible. For that I am indebted to him. (vii-viii)

Doug Kenney [...] lived in Chagrin Falls from 1958 to 1964. His story neither begins nor ends in this midwestern town. Yet it is the place that defined him and by which he defined himself.

"I'm Doug Kenney from Chagrin Falls, Ohio." (2)

"We remember everybody, even if they only lived here for six months," says Jim Vittek. "We remember the way they kicked a soccer ball or threw a football. We remember where they sat in class."

Yet in Chagrin Falls few remember Doug Kenney. It is as if he moved through town invisibly, leaving no fingerprints. It is The Carol Burnett Show's Tim Conway they remember instead. He is Chagrin's favorite son. (2-3)

A response from Hefner and company indicated that a lawsuit would quickly follow if the parody hit the newsstand. Undaunted, Lewis visited Chicago and told Playboy face-to-face that the Lampoon looked forward to all of the press coverage such a suit would bring to its publication. Abruptly, Playboy offered to help out in any way possible and introduced Lewis to the specialty printer that produced their centerfolds. (27)

Sirs:

It says here that you're starting some sort of funny magazine. All I can say is that you people have a lot of nerve. Haven't you looked outside your own selfish egos long enough to see that people are being wronged and oppressed all over the world? Take the fascist military regimes which seem to grow in number every year. In these stricken countries, you can't even look cross-eyed without the secret police writing your name down in little notebooks. It may even be years later that one night you are roused from your sleep by the terrifying sound of rifle butts breaking down your flimsy rattan door. The brutal thug drags you, heedless of your piteous cries, deep, deep into the jungle. Never to return. And you, with your funny magazine.

—Viola da Gamha, South Orange, New Jersey

(The first fictitious letter to the editor appearing in the April 1970 National Lampoon) (58)

When Doug returned to New York he was clearly ambivalent about the idea of getting married. Writer Anne Beatts, who soon joined the magazine, met Doug on a visit to the offices at 635 Madison. The first question Doug asked Beatts, after introductions, was whether he should be getting married. With his wedding only a few weeks away, Beatts thought Doug had bigger problems than his impending marriage if he was asking her advice. Nearly everyone at the magazine had heard the same question time and again. (68)

In between writing industrial copy for Caterpillar, [Sean] Kelly helped create a sixty-second Canadian National Railways ad that featured nothing but plane crashes. The client quickly explained that they were owned by the same company as Air Canada. (76)

"Doug would sometimes tell writers to 'put in a little schmuck bait,''' O'Donoghue said, "things like a kitten playing with a ball of yarn. People see that and go 'Aww ... ' It pulls the schmucks in." (88)

Working long hours suited Doug, because he simply didn't know how to be a married man, nor did he have any idea why he'd gotten married in the first place. (108)

"We decided that the most shocking thing you could do was to really, really start liking Montovani," Hendra recalled.

One night, the two decided to drink and listen to an album of schlock classical music covers and found themselves musing, "That's the most beautiful rendering of Ave Maria I've ever heard," almost unable to determine for themselves whether the comments were kitsch or truly heartfelt. (130)

At one agency, [Brian] McConnachie was assigned to synopsize shows appearing on CBS. Forced to read Mayberry R.F.D. scripts and determine whether any of the characters made negative hairdo references that could reflect badly on Prell Shampoo, McConnachie was bored trying to convey the intricacies of plots best summed up, "Aunt Bee loses her hat." Then suddenly McConnachie embraced the assignment, giving in to the subject matter; the small-town humor of Barney Fife and Gomer Pyle began to seem sublime. There were no real jokes, he thought, it was all in the attitude. Before long, he was composing intricate analyses of each episode, dutifully sending them to his superiors.

"I went from not caring too much to really scaring them," he says. (133-4)

McConnachie found a happy home among the misfits. Though the sweet, pixilated Irishman was neither nasty nor cutting, he made his humor part of the mix both in the magazine and at the office. Once, finding out that a Weight Watchers subscriber had sent an angry letter of complaint after mistakenly receiving a copy of National Lampoon, McConnachie asked a clerk to let him handle the matter, which he did by sending the woman the most offensive issue of the magazine with a note reading, "Sorry for the mistake. B. McConnachie, subscription manager." When another furious letter arrived, he sent the same note and another issue of the wrong magazine. They went back and forth like this for several weeks, ending when McConnachie sent the woman a bill for the issues he'd mailed her.

His story ideas and nonlinear sensibilities were unlike those of anyone else at the magazine. Late one evening, while collaborating on an article, McConnachie called John Weidman at home and asked to meet him at an all-night grocery. Silently walking the aisles, McConnachie pulled a box of laundry detergent from a shelf and excitedly shouted, "See, that's what I've been talking about!"

Wandering into Kelly's office on another late night, McConnachie tried out a cartoon he was writing in which the Pillsbury Dough Boy asks Mr. Peanut, "How's your aunt? The one with the small hands."

"Should it be small feet?" McConnachie asked, leaving the loquacious Kelly temporarily speechless. (134-5)

During his interview, Matty discussed his philosophy of running the magazine. The writers, he said, should pick on everyone. That was part of the formula—nothing is sacred, and the radical leftists were just as repugnant as the John Birch Society. The worst kind of person was the liberal who laughs when they make fun of Nixon, but "draw[s] the line at the Kennedy assassination," saying "that's not funny." (147)

This piece and others resulted in numerous hate and protest letters arriving on O'Donoghue's desk. Yet none provoked as great a response as Beatts's phony Volkswagen ad, depicting the legendary Bug floating in water (one of the auto manufacturer's marketing claims) with the headline, "If Ted Kennedy drove a Volkswagen, he'd be President today."

Almost immediately, Volkswagen began receiving angry letters from consumers who, despite the fact that the parody ran in a something other than a periodical, believed it was the work of the automaker. (171)

Doug and O'Rourke prepared for the project by sitting around the Bank Street apartment, smoking dope and talking about high school. Doug discussed his brother's life at a traditional American public school and his own interest in the middle America of the 1950s. Before long it dawned on them that there were only a certain number of personalities or archetypes that were universally common and applied to nearly every high school this side of Andover. Together they drew up a list of thirty-five personality types that they could parody and make easily recognizable to readers.

"By the end of the evening we realized—Oh, fuck! You really could do this," O'Rourke says. "Once you had the characters and personalities—you had a Trollopian or O'Haraian universe in which things could happen."

Gathering yearbooks from staff, friends, and family, they saw that their perceptions were on the money, with social meanings from which they could derive humor.

"It was chilling to see how much they were all the same," Doug told one reporter about looking at the yearbooks stereotypes. "Bully, clown, intelligent introvert, politician, protohomosexual. It was Nazi social engineering. By weight of social pressure these people became these things." (184)

O'Donoghue's diva act was beginning to wear thin. Deep down he may have respected his colleagues, but even close friends were beginning to feel the sting in a new way. Chris Cerf, who was working on Sesame Street, was often the subject of snide commentary in which O'Donoghue insinuated that he'd sold out. Years later, when working at Saturday Night Live, O'Donoghue refused to write sketches for the Muppets. "I don't write for felt," he would say. (195)

Though not always around, Trow was capable of ruffling feathers on his visits to the office in the name of both humor and spite, once commenting on the wide 1970s necktie of an ad salesman, "Some say it's a necktie, while others think it's a board game." (195)

That day, Henry [Beard] lay in the grass, drunk, staring at the overhead power lines. Silent for a while, he told Kelly that a properly placed charge could black out the whole East Coast. It was how he thought.

"Henry's politics were always nonexistent," Kelly says. "He always liked to think of how you could do the most damage to whatever it was."

Henry was a man trapped within the constraints of his upbringing. Generally quiet and reserved, he became verbally, but never physically, pugilistic when he drank. National Lampoon photographer Pedar Ness remembers a sauced Henry sitting alone at the kitchen table of P. J. O'Rourke's Greenwich Village apartment, repeating over and over to himself, "I showed them. I showed them." When asked what he was talking about, Henry said that his entire family had attended Yale, while he threw caution to the wind by enrolling at Harvard. As rebellions go, Ness thought, this was a fairly small one. (199)

A few days later, Kelly came into the radio show offices one morning to find who he thought was a homeless man (whom he described as "the most unkempt fucked up looking human I'd ever seen"), snoring away on the sofa. Hours later he would be introduced to that man as Brian Doyle-Murray's little brother Bill Murray, who had taken an overnight bus from Chicago. (219)

"Thank god he [John Belushi] wasn't religious," McConnachie wrote. "He could have done some real damage." (230)

The end came in late 1974 when Belushi and Doyle-Murray wrote an entire episode dedicated to the Death Penalty, which viciously lampooned the practice and outraged station managers and advertisers alike. Nearly 400 stations dropped the National Lampoon Radio Hour.

When Matty complained about the fallout, Belushi smiled broadly. "You know 400 stations, that's the record." (231-2)

The collective attitude toward [Ivan] Reitman was exemplified by the first day of rehearsal. Arriving at the theater on a winter day, he was bundled up to fight the cold. As he took off his warm clothing, Reitman said hi to each member of the cast, but on completion was greeted by Murray, who redressed the producer piece by piece, first the coat, then the hat, and finally the scarf—escorted him to the door, slid him out, and closed it behind him. Reitman didn't return for two days. (243)

In early 1976, Susan Devins, who'd just completed her master's degree in library sciences, was hired as an assistant copyeditor at National Lampoon. Early on her first day she received a phone call.

"Cheeseface is dead," the caller said. "Cheeseface the dog is dead."

Someone had tracked down the black-and-white mutt from the January 1973 cover at the farm where he lived and shot him. After initially thinking the call was a joke, Devins realized the bizarre event had actually taken place and that indeed Cheeseface had been assassinated. She burst into tears, thinking, "Oh my god, what have I gotten myself into." (264)

When he turned thirty on December 10, 1976, a female friend arranged a small dinner party in Doug's honor to which she invited the Kenneys. Attempting to make the evening a happy event and provide some of the warmth he so desired, the woman toasted Doug and asked Harry if he was proud of his son who had achieved so much success before the age of thirty.

"Actually it would have been the same if he'd never been born," Harry responded with bitter sarcasm. (282)

As the evil Dean Wormer, Landis wanted Jack Webb, the deadpan, crime-fighting Dragnet star. Over a booze-soaked lunch, however, Webb couldn't understand why anyone would want him in a comedy and turned down the role, after which Landis turned his sights to veteran character actor and film heavy John Vernon, whom he'd seen in Clint Eastwood's The Outlaw Josey Wales. At one point in the film, Vernon, with a blue-eyed squint, delivers the unforgettable line, "Don't piss down my leg and tell me it's raining." Landis thought, "Dean Wormer!" (288)

Sutherland spent two days on the film's Eugene, Oregon, set, commuting from San Francisco, where he was shooting The Invasion of the Body Snatchers. He turned down an offer of profit participation and opted for a fee of $50,000, costing himself somewhere around $15 million. (289)

During a successful run at the Roxy in Los Angeles, stars like Jack Nicholson turned out and laughed, while Laverne and Shirley star Cindy Williams upbraided the cast for "Jackie Christ" and another piece in which the cast gave the crowd the finger.

"That was the least funny thing I've ever seen in my life!" she shrieked.

"You clearly don't watch your own program," Moses shot back. (290)

Mount, Landis, and Reitman sent the Animal House script to university presidents and college administrators across the United States, meeting with rejection everywhere but the University of Oregon, whose dean of students, while working at another university, had refused to let Mike Nichols shoot The Graduate on the campus because he didn't like the script. Realizing that his strength was in academia and not film criticism, he let Landis have the campus for thirty-two days in summer 1977. (295)

During another screening, Tanen insisted that Landis remove the scene where Boon, Pinto, Otter, and Flounder visit the all-black Dexter Lake Club where Otis Day and the Knights are playing. Believing it would be offensive to African Americans, Tanen claimed that it would start race riots in theaters showing the film. Promising Tanen they'd try to remove the scene, Mount and Daniel spent several weeks wondering whether it might be objectionable to black audiences. Mount then called in Richard Pryor, with whom he'd worked on Car Wash.

Pryor and Mount watched the film alone in a screening room on he Universal lot. As the lights came up, Mount asked Pryor whether he considered the scene offensive.

"No, man," Pryor chuckled. "It's just fucking funny. And you know what else is funny?"

"No," Mount replied.

"White people," Pryor said. "White people are funny."

The scene stayed. (299)

Beyond his editorial skills, O'Rourke's demeanor was difficult. While capable of greater warmth and generosity than Henry, he also flew into rages, screaming, breaking things, and punching his fist through office walls. It was from O'Rourke that Aaron learned the expression "go eat a bowl of suck." Aaron and others were walking on eggshells, fearing the next explosion. (305)

"In the wake of Animal House and Saturday Night Live, young, darkly comedic talent could go to Hollywood and make $100,000," O'Rourke says. "When the Lampoon started, young, darkly comedic talent could go to hell and be glad of the cheap rents." (310)

Since the film's release, Landis has been approached time and again by people who believed deep in their hearts that they themselves were members of the Delta/Animal House on their college campuses. Nobody has ever claimed to be an Omega, not even the innumerable senators (including Sam Ervin), CEOs, and other men who dearly did not while away their college days drinking nonstop and trying to subvert authority. (313)

Doug, Greisman, and Shamberg created Three Wheel Productions, which would be dedicated to making films written, developed, and possibly directed by Doug. In his first official act, Doug designed company stationery with a logo that depicted a sleazy agent type, dripping in jewelry and leaning on a Jaguar sports car, beneath which was emblazoned the motto See You in Court. (316)

Though he had dreamed of Hollywood and the film business, there was no sense that Doug was thrilled to be there. Something about it seemed cheap and artificial to him, as if the Yearbook, with its idiotic and brutal teenage social order, had sprouted up on the Pacific. (317)

One thing that quickly became apparent was that Dangerfield's performance [in Caddyshack] was both hilarious and thoroughly unprofessional. No one on the set had noticed that after Rodney uttered a line he completely turned off and stopped acting. As the other actors spoke, Dangerfield looked at them as if they were insane. (345)

Little is certain about Doug Kenney's death. Like the inner workings of his brain, the content of his humor, and the way he lived—it is shot through with ambivalence. Perhaps the best explanation is this: it was an accident that was no accident. Often reckless and given to taking chances, a stoned Doug took a risk, walking past danger signs into oblivion. He didn't want to die, but put himself in a position to do so. It seems to be most fitting conclusion, though an uncertain one. (369)

|