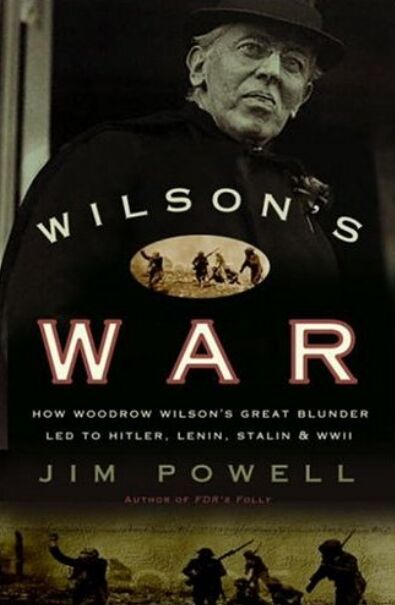

Wilson's War: How Woodrow Wilson's Great Blunder Led To Hitler, Lenin, Stalin, and World War II

Jim Powell (2005)

Wilson made a decision that led to tens of millions of deaths. Far from helping "make the world safe for democracy," as he claimed, he contributed to the rise of some of the most murderous dictators who ever lived. No other U.S. president has had a hand—however unintentional—in so much destruction. Wilson surely ranks as the worst president in American history.

Wilson's fateful decision was for the United States to enter World War I. This had horrifying consequences.

First, American entry enabled the Allies-principally Britain and France-to win a decisive victory and dictate harsh surrender terms on the losers, principally Germany.

Until the United States entered the war, which had begun in August 1914, it was stalemated. The British and French together always had more soldiers on the Western Front than the Germans, but the Germans had smarter generals and more guns. The British navy maintained a blockade that prevented the Germans from importing just about anything, including food, and the Germans had no way to invade England. Both sides suffered millions of fatalities, and their fighting forces were weary. Neither side had the capacity to dictate harsh terms to the other. (1-2)

After Lenin's death on January 21, 1924, his comrade Joseph Stalin outmaneuvered rivals to seize power and commit an unprecedented number of mass murders. We wouldn't have had Stalin without Lenin, and Lenin probably would have been a forgotten man if Woodrow Wilson hadn't pressured and bribed the Provisional Government to stay in World War I. (10)

The consequences of Wilson's fateful decision to enter World War I played out long after he died in 1924, because of Hitler, Lenin, and Stalin. Those ruthless killers would not have come to power as they did if the United States had stayed out of the war. Their crimes are part of Wilson's story, ignored in Wilson biographies and history books. Wilson biographies, like other biographies, typically end with the subject's death. American history books focus on the ways World I War affected Americans; these books say little, if anything, about how Wilson's decision played out in Germany and Russia. Conversely, books about German and Russian history say little about Wilson, although they make clear the consequences of keeping Russia in the war and imposing vindictive surrender terms on Germany.

This is the first book attempting to tell how the consequences of Wilson's decision played out in both Germany and Russia. Moreover, Hitler and Stalin were the principal instigators of World War II, so that's a consequence of Wilson's decision—part of his story. After World War II, Stalin grabbed Eastern Europe and provoked the Cold War, and Wilson's legacy continued. The Cold War involved two major hot wars—Korea and Vietnam—and the United States entered both in the Wilsonian tradition of trying to do good even when there wasn't a direct threat to America's national security. Wilson's shadow has loomed over the Middle East as well, since bitter adversaries were forced into a new nation—Iraq—thanks to the Versailles treaty made possibly by Wilson. (14-15)

Austria enacted schooling laws to extend the political power of the dominant German-speaking minority. "Schools were designed to send forth obedient subjects, not critically-minded citizens," according to historian Arthur J. May. "The object of Austrian elementary education, above all other objects, was to contribute to the preservation of the state." (46-7)

How could Germany and Russia fight each other? Kaiser Wilhelm II was a cousin of Czar Nicholas II and—one might add—an uncle of Britain's King Edward VII. Surely, royals ought to be able to talk with one another and avoid a war. (50)

What if soldiers refused to charge into the machine-gun fire? Well, the French Ministry of War ordered that its soldiers be exeuted—shot within twenty-four hours. No trial. General Joffre declared, "We must be pitiless with the fugitives." The British had the same policy of killing their own soldiers if the Germans didn't do it. (57)

German submarine commanders couldn't easily identify ships in their sights, and they couldn't remove passengers or goods, so the Germans declared that the most practical policy was to provide fair warning: ships in a certain area would be at risk. In February 1915 they announced that the waters around the British Isles were a war zone—the Germans even paid for advertisements in New York newspapers, warning Americans to stay out of the war zone.

This policy became explosively controversial when, on May 7, 1915, a German submarine sank the Lusitania, a British ship carrying 118 American passengers. President Woodrow Wilson expressed outrage. Although it was absurd for Americans to believe they were entitled to safe passage in a war zone, particularly on ships sailing under belligerent flags, the Germans curtailed their use of submarine warfare for two years. Only later was it revealed that the Lusitania was carrying 173 tons of rifle cartridges and shrapnel destined for Britain. (59-60)

Altogether, reported historian Martin Gilbert, some 750,000 German civilians perished as a consequence of· Britain's naval blockade. (62)

Much has been written about economic and social forces supposedly driving history, but World War I and its unexpected consequences illustrate the crucial role of individuals. What gave Woodrow Wilson, the idea that he could do good by participating in a senseless bloodbath? How did he imagine that he could impose his will on millions of angry, bitter people who lived thousands of miles away? Why squander tens of thousands of American lives when nobody had attacked the United States? How much better might history have turned out if the president of the United States had been someone with more humility? (73)

Wilson began a college teaching career at Bryn Mawr, but he found he wasn't comfortable teaching women. He acknowledged he had a "chilled, scandalized feeling that always comes over me when I see and hear women speak in public." (74)

On April 21, American marines landed and began occupying facilities along the half-mile-long Veracruz port area. Wilson had been told there wouldn't be any resistance, but Mexican general Gustavo Maas was outraged at the American landing and organized resistance. There were twenty-four American casualties the first day. Since Mexican snipers continued to fire at American positions, it was decided that American forces had to move throughout Veracruz to suppress resistance and establish order. This involved searching every house! When marines were finished searching one house, they blasted holes in the wall abutting the next house, then went right in, avoiding Mexican sniper fire on the streets. (83-4)

Although Wilson's intervention in Mexico brought nothing but trouble, he had the arrogance to insist he would do good by intervening in the vastly more complicated and deadly European war. With some humility, Wilson might have realized that if the U.S. Army couldn't catch a Mexican bandit, it was probably going to have difficulty trying to "make the world safe for democracy." (88)

It was curious how Wilson could imagine himself making the world safe for democracy by allying with Britain and France, since both nations were determined to hold on to their colonial empires. France had rapidly expanded its colonial holdings since 1870, in Africa and East Asia. The French had a reputation for brutal colonial rule. In erms of global extent, the British Empire was unmatched in human history, with a presence in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. During World War I, Britain was trying to suppress the Irish struggle for independence.

The most brutal colonial rulers were the Belgians—British and French allies—who murdered perhaps 8 million people in the Congo, a colony personally owned by Belgium's King Leopold II. The death toll has been estimated as high as 10 million. Most of the murders occurred between 1890 and 1910. Leopold ordered that officials continuously conduct ivory raids, shooting elephants, seizing or buying (for a few trinkets) ivory to be shipped back to Europe. Ivory was carried by slave porters from the interior to the seaports, and very few of these people survived for long. They walked barefoot, with chains around their necks. The porters were often guarded by black men who themselves were slaves, and these guards, in turn, were controlled by Belgian soldiers.

Belgian murders in the Congo accelerated with the growing demand for rubber, used to make bicycle and car tires. African rubber was made from the sap of a vine that flourished in the Congo. By the late 1890s,. Leopold was collecting more revenue from rubber than from ivory. He had soldiers go from village to village seizing hostages who might be returned when local people gathered enough rubber. Sometimes the Belgians paid for rubber by giving village chiefs captives who could be eaten or used as slaves. When the Belgians encountered resistance, they shot everyone they could find in a village and cut off the victims' right hands as a signature. Occasionally ears and noses were cut off, but right hands were favored. They were smoked, gathered in baskets, and delivered to Belgian inspectors. Leopold spent much of his blood money building palaces, parks, and monuments around Belgium. (93)

Europeans had been fighting one another for thousands of years, and they were determined to continue fighting. There was much wisdom in the traditional American policy that Wilson ignored: namely, stay out of other people's wars. (95)

His speech was loaded with glittering generalities. "The world must be made safe for democracy," he declared. He didn't explain how this was to be done by allying with the British Empire, which had colonies around the world; with France, which had colonies in Africa and Asia; and with Russia, which was ruled by a czar. (98)

A month later, on May 28, Wilson issued a proclamation accompanying his bill to establish military conscription. All young men between twenty-one and thirty years old had to register for conscription, and anyone who refused to appear when summoned was subject to imprisonment. Wilson tried to downplay the fact that military conscription was a form of involuntary servitude—slavery—by offering a fatuous claim that "it is in no sense a conscription of the unwilling; it is, rather, selection from a nation which has volunteered in mass." (98)

If peace was what Wilson wanted, he should have stayed out of the war. But he would have needed humility to recognize that he could only try to control what the United States did. He couldn't possibly control what other people did, especially considering the deep hatreds that had intensified during the war.

Consumed by ambition to be a world statesman, Wilson was simply pursuing his self-interest as a politician. He had dreams of glory, telling other people what to do at the peace settlement. What other people actually did at the peace settlement, of course, would be another matter, but Wilson doesn't seem to have thought much about that. For him to participate in the settlement, the United States had to join the war. Wilson seems to have made his decision, probably the most fateful decision of the twentieth century, without seriously considering the possible consequences. (99)

It would have been hard for taxes to cover Russia's war spending. [. . .] I Borrowing provided some funds, mainly by selling bonds to Britain, the proceeds used to buy war materials from Britain and the United States. But mainly what the government did was print money—inflation. The government abandoned the gold standard that obliged it to pay a ruble's worth of gold when presented with a ruble's worth of paper. Since gold was rare, the supply of gold was much more difficult to increase than the supply of paper money, so the gold standard limited the amount of paper money that could be issued. Going off the gold standard eliminated this constraint. Historians estimate that the Russian money supply soared between 400 and 600 percent by January 1917.

As a consequence, prices soared. "In Simbirsk [now Ulyanovsk], for instance," Stone explained, "a pair of boots that cost seven rubles before the war cost thirty in 1916; in Ivanovo-Voznesensk, calico products rose to 319 per cent of their pre-war price in September 1916; horse-shoe nails, which cost three rubles and forty kopecks in 1914 rose, early in 1916, to forty rubles." (119)

What if a member were attacked? Article 1l: "Any war or threat of war, whether immediately affecting any of the Members of the League or not, is hereby declared a matter of concern to the whole League, and the League shall take any action that may be deemed wise and effectual to safeguard the peace of nations."

So the League of Nations amounted to a traditional alliance, and an attack on one member would oblige other members to join the conflict, expanding it—which, of course, is how World War I happened in the first place: a Serbian nationalist assassinated Archduke Ferdinand; Austria threatened Serbia; Russia came to the defense of Serbia; Germany came to the defense of Austria; France came to the defense of Russia; and Britain came to the defense of France and Russia. By the time this process was done, Bulgaria, Italy, Japan, and Turkey were involved, too.

There was talk about the League of Nations having its own armed force, but it was easy to imagine power struggles for control of such a force—as has always happened when people disagreed about how force should be used. (150-1)

Americans would be taxed, and American soldiers would , be sent to die, in an effort to resolve conflicts that had little if anything to do with American vital interests, never mind national defense. (152)

The most serious blunder was made not at the 1919 Paris Conference but in Washington, when in 1917 Wilson decided to bring the United States into the war, enabling the Allies to win a decisive victory and dictate the harsh surrender terms. Having done this, he unleashed forces that soon exploded around the world. (159)

President Wilson utterly misunderstood what was going on in Russia. Socialist revolutionaries of various stripes were struggling for power, and all wanted government control of the economy. It never occurred to Wilson that government control of the economy would make possible government control of everything else. The result would probably be a totalitarian regime and reign of terror such as developed during the French Revolution. In his April 2, 1917, war message, Wilson hailed Russian socialist revolutionaries as "forces that are fighting for freedom in the world, for justice, and for peace." Wilson seemed to have no idea that by pressuring the Russian Provisional Government to stay in the war, he was playing with fire.

So when Lenin arrived in Petrograd, he didn't encounter celebrations of peace that would have doomed his revolutionary dreams; instead he found chaos. He began planning how he could exploit that chaos to overthrow the Provisional Government. It was an unintended gift from Woodrow Wilson and his allies. (163-4)

It had been estimated that the offensive might involve 6,000 Russian battle deaths. In fact, about 400,000 Russians died in battle, and hundreds of thousands of soldiers deserted. Altogether, the Grand Offensive brought total World War I Russian casualties to an estimated 1.7 million killed and 4.9 million wounded, and there were approximately 3.9, million Russian prisoners of war. How could Woodrow Wilson, in his wildest dreams, have imagined that the Provisional Government would remain in power by continuing the war and piling more horrors upon horrors? (169)

Like the other belligerents, Germany had spent money assuming it would win the war and be able to push war costs on its enemies. All the belligerents had financed the war mostly by borrowing. (183)

Borrowing wasn't enough to cover Germany's war costs, so the government resorted to inflation—a form of tax. (184)

Hayenstein bragged about how much paper money his printers could turn out. At one point, a strike at a money-printing plant stopped the production of currency—and the inflation stopped! Unfortunately, Havenstein was able to arrange for other people to resume the operation of the printing presses, and inflation resumed.

He inflated both to finance current war costs and payback loans with depreciated currency. The process started at the beginning of the war. Prior to it, coins accounted for between 52 percent and 65 percent of money in circulation. Germany had become an industrial powerhouse by honoring the gold standard, which assured everybody that German paper money and its unit of account—the mark—was likely to retain its value in the future, because by law the amount of currency in circulation could not be more than three times the amount of gold in the government's vaults. The ultimate check on power of the Reichsbank was the ability of the people to redeem their paper money for gold.

During the last week of July 1914, more and more Germans realized that war was likely, and they were frantic to protect their savings as people have done for thousands of years—with gold and silver. These precious metals were scarce and costly to mine, so the supply couldn't be arbitrarily inflated like paper money. Gold and silver were cherished for their beauty, which was why they were fashioned into jewelry. They were durable—they didn't rot, break, or burn. And so thousands of Germans lined up around the Reichsbank building in Berlin, hoping to redeem their paper money for gold and silver. The Reichsbank paid out 163 million marks' worth of the precious metals. On July 31, to prevent the further dedine of its hoard, the Reichsbank broke the law, abandoned the gold standard, and refused to payout any more gold.

This enabled the Reichsbank to finance the war by stepping up the printing of paper money—no obligation to exchange any of it for gold or silver. At the beginning of the war, a reported 7.4 billion marks' worth of currency were in circulation. This soared to 44 billion by the end of the war.

Then the Reichsbank began a propaganda campaign, urging Germans to bring in their gold in exchange for paper money. A typical poster said, "Gold for the Fatherland! Increase our gold stock! Bring your jewelry to the gold purchasing bureaus. Full gold value will be given in return!" There was a campaign urging children to hector their parents about surrendering their gold for paper money.

Germany's defeat meant it was stuck with its war debts. The Versailles Treaty further undermined Germany's financial condition in two ways: the loss of territories and business assets reduced the government's potential for tax revenue, while reparations added to expenditures. (184-5)

Bolsheviks banned private trade and declared that traders were lishenets—disenfranchised people without rights. The results were terror, famine, and cannibalism. (187)

In an effort to prevent the new issues of money from leading to higher prices, on July, 7, 1921, the Reich Supreme Court ruled that when sellers priced their goods, they couldn't fully factor in the depreciation of the mark. To illustrate what such a policy led to, Feldman related the story about "a rope manufacturer who had become convinced he could do splendid business by selling his rope for ever increasing amounts of paper marks. He rapidly became a millionaire and then a billionaire, but each time he used his capital to buy hemp, he noted that he progressively received less hemp for more money and that his production steadily decreased. Finally, the day came when he could produce only one piece of rope, and he used it to hang himself at the gate of his desolated factory." (188)

With this collapse of the German economy, the value of the mark plunged. On July 1, 1923, one U.S. dollar would buy 160,000 marks. By August it would buy a million marks.

Taxes didn't begin to cover the costs of reparations, passive resistance, and the welfare state, so the Weimar government accelerated the printing of paper money, but as the money circulated, and people used it to bid up prices for goods and services the paper money didn't buy as much as it used to, and the government further accelerated the money-printing. (190)

Bank depositors were wiped out. "A man who thought he had a small fortune in the bank," [Konrad] Heiden wrote, "might receive a letter from the directors: 'The bank deeply regrets that it can no longer administer your deposit of sixty-eight thousand marks, since the costs are all out of proportion to the capital. We are therefore taking the liberty of returning your capital. Since we have no bank-notes in small enough denominations at our disposal, we have rounded out the sum to one million marks. Enclosure: 1,000,000-mark bill.' A cancelled stamp for five million marks adorned the envelope." (192)

By this time, of course, not many foreigners were willing to accept marks, either. The government desperately sought to borrow dollars abroad, to buy food and avoid having people starve. The goveernment pressured big businesses to loan it gold marks. Incredibly, the government—which caused the inflation—tried to put taxes on a gold basis, meaning that taxes would be indexed and go up exponentially along with everything else during the inflation.

Heiden described the impact of the inflation about as well as anybody ever has: "The State wiped out property, livelihood, personality, squeezed and pared down the individual, destroyed his faith in himself by destroying his property—or stores: his faith and hope in property. Minds were ripe for the great destruction." (192)

Throughout all this, few in the government seemed to understand what was going on. As Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises noted, "Herr Havenstein, the governor of the Reichsbank, honestly believed that the continuous issue of new notes had nothing to do with the rise of commodity prices, wages, and foreign exchanges. This rise he attributed to the machinations of speculators and profiteers and to intrigues on the part of internal and external foes. Such indeed was the general belief. Nobody durst venture to oppose it without incurring the risk of being denounced both as a traitor to his country and as an abettor of profiteering." Mises's first major work, The Theory of Money and Credit (1912), explained how increasing the quantity of money generated upward pressure on prices, regardless of where this was done. (196)

From the very beginning, the Bolshevik regime was based on hostage-taking, concentration camps, and mass murder. In June, Lenin wrote Gregory Zinoviev, chairman of the Council of Commissars: "It is of supreme importance that we encourage and make use of the energy of mass terror directed against the counterrevolutionaries, especially those of Petrograd, whose example is decisive." Lenin told People's Commissar of Food Aleksandr Tsyurupa: "In all grain-producing areas, twenty-five designated hostages drawn from the best-off of the local inhabitants will answer with their lives for any failure in the requisitioning plan." (204)

During the first six months of 1918, Pipes reported, "the Bolsheviks printed between 2 million and 3 million rubles a month. By January 1919 there were reportedly 61.3 billion rubles in circulation, and at the end of the year this had soared to 225 billion rubles. Currency in circulation exploded fivefold to 1.2 trillion rubles in 1920, and 2.3 trillion rubles in 1921. As a consequence of this paper money inflation, prices of goods skyrocketed 10 million times! In free markets, a pint of milk reportedly cost 500 rubles, a pound of meat 3,000 and a pound of butter 5,000." (209)

The Bolsheviks failed to understand that prices were extraordinarily efficient signals, enabling producers to determine what they could produce and what consumers wanted. Market participants don't need to know one another, they might not like one another, and they might be thousands of miles apart, but they can interpret prices to determine the current market situation, even if they don't know what's causing it. When, for instance, Bolshevik officials interfered in market processes and set prices too low, they didn't seem to realize they were simultaneously signaling producers to produce less and consumers to demand more. By paying workers less than they were worth, the Bolsheviks discouraged work, and to get what they considered essential work done, they reintroduced serfdom and slavery, which had disappeared in the Western world. (210)

Peasants yearned for independence, which posed a serious political problem for the Bolsheviks. Karl Radek, a member of the Bolshevik Central Committee, reflected, "The peasants had just received the land from the state, they had just returned home from the front, they had kept their guns, and their attitude to the state could be summed up as 'Who needs it?' They couldn't have cared less about it. If we had decided to come up with some sort of food tax, it wouldn't have worked, for none of the state apparatus remained. The old order had disappeared, and the peasants wouldn't have handed over anything without actually being forced. Our task at the beginning of 1918 was quite simple: we had to make the peasants understand two quite simple things: that the state had some claim on what they produced, and that it had the means to exercise those rights." (214)

There was a succession of mobilization decrees for Former Railway Workers (January 20, 1920), Workers in the Sugar Industries (March 24,1920), Mining Workers (April 16, 1920), Construction Workers (May 5, 1920), Statistical Workers (June 2, 1920), Medical Personnel (July 14,1920), Workers Formerly Employed in Fishing Industries (August 6, 1920), Workers in Wool Industries (August 13, 1920), Domestic Servants (August 31, 1920), Women for Sewing Underwear for Red Army Men (October 30, 1920), and Tailors and Shoemakers Who Worked in Great Britain and the United States (October 1920), among others. (221)

On January 29, 1920, there was a proclamation of universal forced labor. It authorized the establishment of the Central Committee on Compulsory Labor. This, in turn, started bureaucracies such as the Central Extraordinary Commission on Firewood and Cartage Duty, or Tsechrezkomtopguzh. (222)

That Hitler finally became chancellor was the result of many bad breaks. If Woodrow Wilson had kept the United States out of World War I, and neither side were able to dictate surrender terms to the other, there probably would have been some kind of negotiated settlement, the Treaty of Versailles never would have developed as it did, and there surely wouldn't have been the bitter nationalist reaction that generated political support for Hitler. Without the reparations bills and the French occupation of the Ruhr, both of which were a consequence of the decisive defeat of Germany, made possible by American entry in the war, there might not have been the ruinous runaway inflation that enabled Hitler to recruit thousands of Nazis.

After Hitler's conviction for treason, he wouldn't have been treated leniently if the presiding judge hadn't shared Hitler's resentment at how Germany had been humiliated and impoverished. Hitler would have been more likely to serve his full term, in which case he would have been unavailable to help rebuild the Nazi party in ime to take advantage of the depression crisis.

If the prosperity of the Weimar Republic had continued, there wouldn't have been much interest in Hitler's tirades—recall the Nazi party's dismal showing in the 1928 Reichstag elections. Hitler needed the widely shared bitterness of depression as well as the bitterness of war and the bitterness of inflation to give him a large audience. (244-5)

The day after the [Reichstag] fire, Hitler issued a decree, signed by Hindenburg, that suspended Weimar Republic guarantees of civil liberties. It said, in part: "Restrictions on personal liberty, on the right of free expression of opinion, including freedom of the Press; on the rights of assembly and association; violations of the privacy of postal, telegraphic and telephonic communications; warrants for house searches; orders for confiscation as well as restrictions on property, are permissible beyond the legal limits otherwise prescribed." (246-7)

[After the Night of Long Knives,] Hitler was praised for taking decisive action to save the nation from the lawless SA. Minister of Defense Blomberg praised Hitler's "soldierly determination and exemplary courage." Hindenburg praised Hitler for his "determined action and gallant personal intervention." Just in case people changed their minds, Hitler secured passage of the Law for the Emergency Defense of the State, which said, in part, "The measures taken on 30 June and 1 and 2 July for the suppression of high treasonable and state treasonable attacks are, as emergency defense of the state, legal." (252)

If it hadn't been for Woodrow Wilson, Joseph Stalin might have ended his days as a petty bandit in his native province of Georgia. Instead, Wilson pressured Russia's Provisional Government to stay in World War I, accelerating the collapse of the Russian army until there was hardly anybody left to defend the government. Lenin seized power in November 1917, and Stalin, once he gained control of the regime Lenin had established, murdered millions. (254)

Increasing numbers of peasants ran away from farms and hoped to find a better life in cities. To prevent this, the government began issuing identity papers and required that residents register with local authorities. (260-1)

There were reports of cannibalism. For instance, this bulletin about Kharkiv: "Every night the bodies of more than 250 people who have died from hunger or typhus are collected. Many of these bodies have had the liver removed, through a large slit in the abdomen. The police finally picked up some of these mysterious 'amputators' who confessed they were using the meat as a filling for the meat pies they were selling in the market." (261)

Resistance to Stalin's maneuvers was undermined by extracting "confessions" that implicated his adversaries. A principal method was "the conveyor." Robert Conquest described it as "continual interrogation by relays of police for hours and days on end. As with many phenomena of the Stalin period, it has the advantage that it could not easily be condemned by any simple principle. Clearly, it amounted to unfair pressure after a certain time and to actual physical torture later still, but when? No absolutely precise answer could be given.

"But at any rate, after even twelve hours, it is extremely uncomfortable. After a day, it becomes very hard. And after two or three days, the victim is physically poisoned by fatigue . . . though some prisoners had been known to resist torture, it was almost unheard of for the conveyor not to succeed if kept up long enough. One week is reported as enough to break almost anybody. A description by a Soviet woman writer who experienced it speaks of seven days without sleep or food, the seventh standing up—ending in physical collapse." (266)

As Robert Conquest explained, Bolshevik victims "were hit in the stomach with a sandbag; this was sometimes fatal. A doctor would certify that a prisoner who had died of it had suffered from a malign tumor. Another interrogation method was the stoika. It consisted of standing a prisoner against a wall on tiptoe and making him hold that position for several hours. A day or two of this was said to be enough to break almost anyone." (270)

Since the camps were cut off from the outside world by the stormy Sea of Okhotsk, prisoners were thoroughly demoralized. The principal method of killing was brutal labor, starvation, and exposure to temperatures reaching almost sixty degrees, Fahrenheit below zero. Conquest reported that "in some camps, when cpmmunications were restored, it was found that no one was left, not even the dogs. According to one story a convoy lost its way and died, several thousand prisoners with their guards, to a man." During the summers, prisoners were overwhelmed by insects. Conquest: "One specially large type of gadfly can sting through deer hide, and drives horses crazy."

Among the few lucky survivors was general Aleksandr. V. Gorbatov, who wrote a memoir of his experiences, Years Off My Life. He had been sent, to Kolyma in 1938. Guards encouraged violence among the prisoners, and his boots were stolen—an open invitation to frostbite. Gorbatov slept in a tent covered with snow. Meager rations contributed to deficiency diseases. "My legs began to swell and my teeth grew loose in my gums," he wrote. "My legs went on swelling until they looked like logs, and my knees would no longer bend." Apparently he was saved by the war with Germany, when Stalin realized he needed military commanders.

Franklin D. Roosevelt's vice president, Henry Wallace, spent three days in Kolyma on his way to China. He was accompanied by fellow Soviet sympathizer Owen Lattimore, from the Office of War Information. Wallace subsequently wrote Soviet Asia Mission, a book that gushed about how the prisoners were "pioneers of the machine age, builders of cities." He passed along the fiction that "Kolyma miners had gone east to earn more money." He reported on communities "founded by volunteers. (275-6)

Incredibly, none of this was inevitable. Stalin wouldn't have been in power if Lenin hadn't seized power, and Lenin probably wouldn't lave been able to do that if Woodrow Wilson hadn't brought the United States into World War I and pressured and bribed Russia's Provisional Government to stay in the war until it and the Russian army disintegrated. (279)

By 1939, Woodrow Wilson had heen dead for fifteen years, but the consequences of his decision to enter World War I were still playing out in Germany and Russia. Both Hitler and Stalin had taken advantage of Wilson's blunder to establish brutal totalitarian regimes. Hitler and Stalin were bitter enemies, but when circumstances brought them together, the result added a world war to Wilson's legacy. (280)

At the time, the German army was still limited to 100,000 men by the terms of the Versailles Treaty. Hitler declared, "My program was to abolish the Treaty of Versailles. It is nonsense for the rest of the world to pretend that I did not reveal this program until 1933, or 1935, or 1937. Instead of listening to this foolish chatter of emigres, these gentlemen would have been wiser to read what I have written and rewritten thousands of times. No human being has declared or recorded what he wanted more often than I. Again and again I wrote these words—the Abolition of the Treaty of Versailles." (281)

Having done so much, to provoke bitterness in Germany during the treaty negotiations at Versailles, the French didn't maintain armed forces capable of dealing with the consequences of such bitterness. On their own they could not intervene to prevent German rearmament, and the British weren't interested in an intervention that would amount to another war. Nor were the United States, whose intervention in World War I had enabled the British and French to humiliate the Gernans; the American people had become disillusioned with Woodrow Wilson's idea of entering European wars. (282)

Concerned about Hitler's aggressive policies, on April 15, 1939, Britain proposed to Soviet foreign minister Maxim Litvinov that the two countries help each other in the event of an attack.

Subsequent diplomatic exchanges showed that the British either didn't give the negotiation a high priority or were trying to drag out the process. As A. J. P. Taylor explained, "The Soviet counter-proposal came two days later, on 17 April. The British took three weeks before designing an answer on 9 May; the Soviet delay was then five days. The British then took thirteen days; the Soviet government answered within twenty-four hours. Thereafter the pace quickened. The British tried again in five days' time; the. Soviet answer came within twenty-four hours. The British next needed nine days; the Soviet two. Five more days for the British; one day for the Russians. Eight days on the British side; Soviet answer on the same day. With that the exchange virtually ended."

Moreover, Britain dispatched an attache—not its foreign secretary—to pursue discussions with the Soviets. As a low-ranking official, the attache wasn't empowered to make any commitments. It didn't help that the attache traveled by sea rather than by air, suggesting the British didn't feel there were any urgent matters to talk about. The Munich Agreement had convinced Stalin that the British weren't going to take action against Hitler, and his experiences trying to negotiate a pact with the British confirmed this view. (284)

Miraculously, [Molotov] survived all the purges. He was reportedly the only person to shake hands with Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, Himmler, Goring, Churchill, and Roosevelt. (286)

Hitler, of course, wasn't able to savor revenge for long. He invaded Russia in June 1941 and soon became overstretched. Roosevelt and Churchill found themselves allied with Stalin. Although they defeated Hitler, Stalin grabbed Eastern Europe, and the Cold War began almost immediately.

Woodrow Wilson's tortured legacy would extend for another half-century. (289)

The worst American foreign policy disasters of the last century have been consequences of Wilsonian interventionism. Critics have been dismissed as "isolationists," but the fact is that Wilsonian interventionism has dragged the United States into pointless wars and ushered in revolution, terror, runaway inflation, dictatorship, and mass murder. It is past time to judge Wilsonian interventionism by its consequences, not the good intentions expressed in political speeches, because they haven't worked out. (290)

Wilson claimed that American national security was linked with the fate of Britain, but because the British navy had bottled up the German navy and neutralized German submarines, Germany wasn't capable of invading Britain. In, any case, Britain was struggling to maintain its global empire. The settlement following World War I had the effect of adding more territories to the British Empire. Why should American lives have been lost and American resources spent to expand the British Empire?

Why, for that inatter, should the United States have defended the French or the Belgians? They were defending their overseas empires, and both had shown themselves to be brutal colonial rulers. The Belgians were responsible for slavery and mass murder in the Congo—the first modern genocide, involving an estimated 8 million deaths. (291)

George Washington, as the first president of the United States, wisely counseled his countrymen to stay out of European wars, and this policy was continued by his successor Thomas Jefferson despite French and British interference with U.S. shipping. The United States prospered while the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte organized the first modern police state, conquered Europe, and marched into Russia. (292-3)

Wilson ought to have known he was playing with fire when, at the Versailles Conference following World War I, he participated in redrawing thousands of miles of national borders. He knew how nationalist hatreds had exploded in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and triggered the Balkan wars and World War I. Turkish nationalists expelled some 100,000 Greeks from the Anatolian Peninsula, where many families had lived for over a thousand years, and large numbers of Greek women were raped and Greek men murdered. Turkish nationalists massacred an estimated 1.5 million Armenians.

Woodrow Wilson's decision to enter World War I had serious consequences in Iraq, too. Because the British and French were on the winning side of the war, the League of Nations awarded "mandates" to Britain and France in the region. If the United States had stayed out of World War I, there probably would have been a negotiated settlement, the Ottoman Empire would have survived for a while, and the Middle East wouldn't have been carved up by Britain and France. But, as things turned out, authorized by League of Nations "mandates," British Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill was determined to secure the British navy's access to Persian oil at the least possible cost by installing puppet regimes in the region.

In Mesopotamia, Churchill bolted together the territories of Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra to make Iraq. Although Kurds wanted an independent homeland, their territory was to be part of Iraq. Churchill decided that the best bet for Britain would be a Hashemite ruler. For king, Churchill picked Faisal, eldest son of Sherif Hussein of Mecca. Faisal was an Arabian prince who lived for years in Ottoman Constantinople, then established himself as king of Syria, but was expelled by the French government, which had the League of Nations "mandate" there. The British arranged a plebiscite purporting to show Iraqi support for Faisal. A majority of people in lraq were Shiite Muslims, but Faisal was a Sunni Muslim, and this conflict was to become a huge problem. The Ottomans were Sunni, too, which meant British policy prolonged the era of Sunni dominance over Shiites as they became more resentful. During the thirty-seven years of the Iraqi monarchy, there were fifty-eight changes of parliamentary governments, indicating chronic political instability. All Iraqi rulers since Faisal, including Saddam Hussein, were Sunnis. That Iraq was ruled for three decades by a sadistic murderer like Saddam made clear how the map-drawing game was vastly more complicated than Wilson had imagined. (294-5)

|