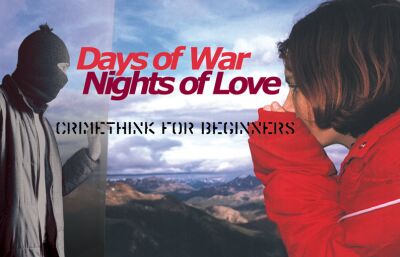

Days of War, Nights of Love

CrimethInc. (2001)

Warning: The word "revolution," which is used constantly throughout these pages with an unironic naiveté, may be amusing or off-putting to the modern reader, convinced as he is that effective resistance to the status quo is impossible and therefore not even worth considering. Gentle reader, we ask that you suspend your disbelief long enough to at least contemplate whether or not such a thing might be worthwhile if it were possible; and then that you suspend it further, long enough to recognize this disbelief for what it is—despair! (6)

As for the contents themselves: we've limited ourselves for the most part to criticism of the established order, because we trust you to do the rest. Heaven is a different place for everyone; hell, at least this particular one, we inhabit in common. (11)

It is more likely that the "normalcy" that these people hold so dear is rather the feelings of normalcy that result from conformity to a standard. Being surrounded by others who behave the same way, who are conditioned to the same routines and expectations, is comforting because it reinforces the idea that one is pursuing the right course: if a great many people make the same decisions and live according to the same customs, then these decisions and customs must be the right ones. (12)

Note: When reading dry political theory, such as the texts you will find on the following pages, it may be useful to apply the Exclamation Point Test from time to time, to determine if the material you are reading is actually relevant to your life. To apply this test, simply go through the text replacing all the punctuation marks at the ends of the sentences with exclamation points. If the results sound absurd when read aloud, then you know you're wasting your time. (19)

Without God, there is no longer any objective standard by which to judge good and evil. This realization was very troubling to philosophers a few decades ago, but it hasn't really had much of an effect in other circles. Most people still seem to think that a universal morality can be grounded in something other than God's laws: in what is good for people, in what is good for society, in what we feel called upon to do. But explanations of why these standards necessarily constitute "universal moral law" are hard to come by. Usually, the arguments for the existence of moral law are emotional rather than rational: "But don't you think rape is wrong?" moralists ask, as if a shared opinion were a proof of universal truth. "But don't you think people need to believe in something greater than themselves?" they appeal, as if needing to believe in something can make it true. Occasionally, they even resort to threats: "but what would happen if everyone decided that there is no good or evil? Wouldn't we all kill each other?"

The real problem with the idea of universal moral law is that it asserts the existence of something that we have no way to know anything about. Believers in good and evil would have us believe that there are "moral truths"—that is, there are things that are morally true of this world, in the same way that it is true that the sky is blue. They claim that it is true of this world that murder is morally wrong just as it is true that water freezes at thirty-two degrees. But we can investigate the freezing temperature of water scientifically: we can measure it and agree together that we have arrived at some kind of "objective" truth, insofar as it is possible. On the other hand, what do we observe if we want to investigate whether it is true that murder is evil? There is no tablet of moral law on a mountaintop for us to consult, there are no commandments carved into the sky above us; all we have to go on are our own instincts and the words of a bunch of priests and other self-appointed moral experts, many of whom don't even agree. As for the words of the priests and moralists, if they can't offer any hard evidence from this world, why should we believe their claims? And regarding our instincts—if we feel that something is right or wrong, that may make it right or wrong for us, but that's not proof that it is universally good or evil. Thus, the idea that there are universal moral laws is mere superstition: it is a claim that things exist in this world which we can never actually experience or learn anything about. And we would do well not to waste our time wondering about things we can never know anything about.

When two people fundamentally disagree over what is right or wrong, there is no way to resolve the debate. There is nothing in this world to which they can refer to see which one is correct—because there really are no universal moral laws, just personal evaluations. So the only important question is where your values come from: do you create them yourself, according to your own desires, or do you accept them from someone else... someone else who has disguised their opinions as "universal truths"? (23-5)

And if the abolition of the myth of moral law somehow causes more strife between human beings, won't that still be better than living as slaves to superstitions? (29)

Because I care about human beings, I want them to be free to do what is right for them. Isn't that more important than mere peace on earth? Isn't freedom, even dangerous freedom, preferable to the safest slavery, to peace bought with ignorance, cowardice, and submission? (30)

It is hierarchy that makes homophobia common among poor people in the U.S.A.—they're desperate to feel more valuable, more significant than somebody. (33)

It is hierarchy at work when your boss insults you or makes sexual advances at you and you can't do anything about it, just as it is when police flaunt their power over you. For power does make people cruel and heartless, and submission does make people cowardly and stupid: and most people in a hierarchical system partake in both. (33)

There are a great deal more anarchists than it seemed, though most wouldn't refer to themselves as such. For most people, when they think about it, want to have the right to live their own lives, to think and act as they see fit. Most people trust themselves to figure out what they should do more than they trust any authority to dictate it to them. Almost everyone is frustrated when they find themselves pushing against faceless, impersonal power.

You don't want to be at the mercy of governments, bureaucracies, police, or other outside forces, do you? Surely you don't let them dictate your entire life. Don't you do what you want to, what you believe in, at least whenever you can get away with it? In our everyday lives, we all are anarchists. Whenever we make decisions for ourselves, whenever we take responsibility for our own actions rather than deferring to some higher power, we are putting anarchism into practice.

So if we are all anarchists by nature, why do we always end up accepting the domination of others, even creating forces to rule over us? Wouldn't you rather figure out how to coexist with your fellow human beings by working it out directly between yourselves, rather than depending on some external set of rules? The system they accept is the one you must live under: if you want your freedom, you can't afford to not be concerned about whether those around you demand control of their lives or not. (35)

Of course, even if a world entirely without hierarchy is possible, we should not have any illusions that any of us will live to see it realized. That should not even be our concern: for it is foolish to arrange your life so that it revolves around something that you will never be able to experience. We should, rather, recognize the patterns of submission and domination in our own lives, and, to the best of our ability, break free of them. We should put the anarchist ideal—no masters, no slaves—into effect in our daily lives however we can. Every time one of us remembers not to accept at face value the authority of the powers that be, each time one of us is able to escape the system of domination for a moment (whether it is by getting away with something forbidden by a teacher or boss, relating to a member of a different social stratum as an equal, etc.), that is a victory for the individual and a blow against hierarchy. (39-40)

Do you still believe that a hierarchy-free society is impossible? There are plenty of examples throughout human history: the bushmen of the Kalahari desert still live together without authorities, never trying to force or command each other to do things, but working together and granting each other freedom and autonomy. Sure, their society is being destroyed by our more warlike one—but that isn't to say that an egalitarian society could not exist that was extremely hostile to, and well-defended against, the encroachments of external power! In Cities of the Red Night, William Burroughs writes about an anarchist pirates' stronghold a few hundred years ago that was just that. (40)

Across almost two millennia, the Catholic Church maintained a stranglehold over life in Europe. It was able to do this because Christianity gave it a monopoly on the meaning of life: everything that was sacred, everything that mattered was not to be found in this world, only in another. Man was impure, profane, trapped in a worthless earth with everything beautiful forever locked beyond his reach, in heaven. Only the Church could act as an intermediary to that other world, and only through it could people approach the meaning of their lives.

Mysticism was the first revolt against this monopoly: determined to experience for themselves a taste of this otherworldly beauty, mystics did whatever it took—starvation, self-flagellation, all kinds of privation—to achieve a moment of divine vision: to pay a visit to heaven, and to return to tell of what blessedness awaited there. The Church grudgingly accepted the first mystics, privately outraged that anyone would sidestep its primacy in all communication with God, but believing rightly that the stories the mystics told would only reinforce the Church's claims that all value and meaning rested in another world. (42)

[Dread Pirate Captain Samuel "Black Sam" Bellamy echoes the pirate who sassed Alexander the Great with the truth):

During the early seventeenth century the port city of Salè on the Moroccan coast became a haven for pirates from all over the world, eventually evolving into a free, proto-anarchist state that attracted, among others, poor, outcast Europeans who came in droves to begin new lives of piracy

preying upon the trade ships of their former home countries. Among these European Renegadoes was the Dread Captain Bellamy; his hunting ground was the Straits of Gibraltar, where all ships with legitimate commerce changed course at the mention of his name, often to no avail. One Captain of a captured merchant vessel was treated to this speech by Bellamy after declining an invitation to join the pirates [and the pirates had voted to burn his sloop]:

I am sorry they won't let you have your sloop again, for I scorn to do anyone a mischief, when it is not to my advantage; damn the sloop, we must sink her, and she might be of use to you. Though you are a sneaking puppy, and so are all those who submit to be governed by laws which rich men have made for their own security; for the cowardly whelps have not the courage otherwise to defend what they get by knavery; but damn ye altogether: damn them for a pack of crafty rascals, and you, who serve them, for a parcel of hen-hearted numbskulls. They vilify us, the scoundrels do, when there is only this difference, they rob the poor under the cover of law, forsooth, and we plunder the rich under protection of our own courage. Had you not better make then one of us, than sneak after these villains for employment?

When the captain replied that his conscience would not let him break the laws of God and man, the pirate Bellamy continued:

You are a devilish conscience rascal, I am a free prince, and I have as much authority to make war on the whole world as he who has a hundred sail of ships at sea, and an army of 100,000 men in the field, and this my conscience tells me; but there is no arguing with such snivelling puppies, who allow superiors to kick them about deck at pleasure. (44)

[adapted from George Orwell's Homage to Catalonia]

Does your father drift from one hobby to another, fruitlessly seeking a meaningful way to spend the little "leisure time" he gets off from work? Does your mother endlessly redecorate the house, going from one room to the next until she can start over at the beginning again? Do you agonize constantly over your future, as if there was some kind of track laid out ahead you—and the world would end if you turned off of it? If the answer to these questions is yes, it sounds like you're in the clutches of the bourgeoisie, the last barbarians on earth. (47)

This perpetual rebellion of the youth also creates deep gulfs between different generations of the bourgeoisie, which play a crucial role in maintaining the existence of the bourgeoisie as such. Because the adults always seem to be the enforcers of the status quo, and the youth do not have the perspective yet to see that their rebellion has also been absorbed into that status quo, generation after generation of young people are able to make the mistake of identifying older people themselves as the source of their misfortunes rather than realizing that these misfortunes are the result of a larger system of misery. They grow older and become bourgeois adults themselves, unable to recognize that they are merely replacing their former enemies, and still unable to bridge the so-called generation gap to learn from people of other age groups... let alone establish some kind of unified resistance with them. Thus the different generations of the bourgeoisie, while seemingly fighting amongst themselves, work together harmoniously as components of the larger social machine to ensure maximum alienation for all. (50)

The people who talk about "human nature" would tell us that this nature consists chiefly of the lust to possess and control. But what about our desires to share, and to act for the sheer sake of acting? Only those who have given up on doing what they want content themselves by finding meaning in what they merely have. Almost everyone knows that it is more rewarding to bring joy to others than it is to take things from them. Acting freely and giving freely are their own reward. Those who think that "from each according to her means, to each according to her needs" unfairly benefits the receivers have simply misunderstood what makes human beings happy. (77)

"Because we don't know when we will die, we get to think of life as an inexhaustible well. But everything happens only a certain number of times, and a very small number, really. How many more times will you remember a certain afternoon of your childhood, some afternoon that is so deeply a part of your being that you can't even conceive of your life without it? Perhaps four or five times more, perhaps not even that. How many more times will you watch the full moon rise? Perhaps twenty. And yet it all seems limitless."

-Gloria Cubana, The Sheltering Sky (88)

Remember how differently time passed when you were twelve years old? One summer was a whole lifetime, and each day passed like a month does for you now. For everything was new: each day held experiences and emotions that you had never encountered before, and by the time that summer was over you had become a different person. Perhaps you felt a wild freedom then that has since deserted you: you felt as if anything could happen, as if your life could end up being virtually anything at all. Now, deeper into that life, it doesn't seem so unpredictable. The things that were once new and transforming have long since lost their freshness and danger, and the future ahead of you seems to have already been determined by your past.

It is thus that each of us is dominated by history: the past lies upon us like a dead hand, guiding and controlling as if from the grave. At the same time as it gives the individual a conception of herself, an "identity," it piles weight upon her that she must fight to shake off if she is to remain light and free enough to continue reinventing her life and herself. It is the same for the artist: even the most challenging innovations eventually become crutches and cliches. Once an artist has come up with one good solution for a creative problem, it is hard for her to break free of it to conceive of other possible solutions. That is why most great artists can only offer a few really revolutionary ideas: they become trapped by the very systems they create, just as these systems trap those who come after. It is hard to do something entirely new when one finds oneself up against a thousand years of painting history and tradition. And this is the same for the lover, for the mathematician and the adventurer: for all, the past is an adversary to action in the present, an ever-increasing force of inertia that must be overcome. (111)

Try thinking of the world as including all past and future time as well as present space. An individual can at least hope to have some control over that part of the world which is in the future; but the past only acts on her, she can never act back upon it. If she thinks of the world (whether that "world" consists of her life, or human history) as consisting of mostly future, proportionately speaking, she will see herself as fairly free to choose her own destiny and exert her will upon the world. But if her world-view places most of the world in the past, that puts her in a position of powerlessness: not only is she unable to act upon or create most of world in which she exists, but what future does remain is already largely predetermined by the effects of events past.

Who, then, would want to be a meaningless fleck near the end of the eight thousand year history of human civilization? Conceiving of the world in such a way can only result in feelings of futility and predetermination. We must think of the world differently to escape this trap—we must instead place our selves and our present day existence where they rightfully belong, in the center of our universe, and shake off the dead weight of the past. Time may well extend before and behind us infinitely, but that is not how we experience the world, and that is not how we must visualize it either, if we want to find any meaning in it. If we dare to throw ourselves into the unknown and unpredictable, to continually seek out situations that force us to be in the present moment, we can break free of the feelings of inevitability and inertia that constrain our lives—and, in those instants, step outside of history.

What does it mean to step outside of history? It means, simply, to step into the present, to step into yourself. Time is compressed to the moment, space is concentrated to one point, and the unprecedented density of life is exhilarating. The rupture that occurs when you shake off everything that has come before is not just a break with the past—you are ripping yourself out of the past-future continuum you had built, hurling yourself into a vacuum where anything can happen and you are forced to remake yourself according to a new design. It is a sensation as terrifying as it is liberating, and nothing false or superfluous can survive it. Without such purges, life becomes so choked up with the dead and dry that it is nearly unliveable—as it is for us, today. (113-14)

History is haunted by its own karma; the moment of revolution, of real poetry, brings all its unsettled debts back into play, to be discharged forever so life can really begin. What we need now are instants so overwhelming, so irresistible, that the entire control system of regulated time melts beneath their scorching radiance. (117)

Our revolution must be an immediate revolution in our daily lives; anything else is not a revolution but a demand that once again people do what they do not want to do and hope that this time, somehow, the compensation will be enough. Those who assume, often unconsciously, that it is impossible to achieve their own desires—and thus, that it is futile to fight for themselves—often end up fighting for an ideal or cause instead. But it is still possible to fight for ourselves, or at least the experiment must be worth a try; so it is crucial that we seek change not in the name of some doctrine or grand cause, but on behalf of ourselves, so that we will be able to live more meaningful lives. Similarly we must seek first and foremost to alter the contents of our own lives in a revolutionary manner, rather than direct our struggle towards world-historical changes which we will not live to witness. In this way we will avoid the feelings of worthlessness and alienation that result from believing that it is necessary to "sacrifice oneself for the cause," and instead live to experience the fruits of our labors. . . in our labors themselves. (118)

Love is subversive, because it poses a threat to the established order of our modern lives. The boring rituals of workday productivity and socialized etiquette will no longer mean anything to a man who has fallen in love, for there are more important forces guiding him than mere inertia and deference to tradition. Marketing strategies that depend upon apathy or insecurity to sell the products that keep the economy running as it does will have no effect upon him. Entertainment designed for passive consumption, which depends upon exhaustion or cynicism in the viewer, will not interest him.

There is no place for the passionate, romantic lover in today's world, business or private. For he can see that it might be more worthwhile to hitchhike to Alaska (or to sit in the park and watch the clouds sail by) with his sweetheart than to study for his calculus exam or sell real estate, and if he decides that it is, he will have the courage to do it rather than be tormented by unsatisfied longing. He knows that breaking into a cemetery and making love under the stars will make for a much more memorable night than watching television ever could. So love poses a threat to our consumer-driven economy, which depends upon consumption of (largely useless) products and the labor that this consumption necessitates to perpetuate itself.

Similarly, love poses a threat to our political system, for it is difficult to convince a man who has a lot to live for in his personal relationships to be willing to fight and die for an abstraction such as the state; for that matter, it may be difficult to convince him to even pay taxes. It poses a threat to cultures of all kinds, for when human beings are given wisdom and valor by true love they will not be held back by traditions or customs which are irrelevant to the feelings that guide them. (151-2)

Countless generations have set out convinced that they would succeed where other had failed – that's where lawyers and reporters come from, you know. They're the cynical corpses of idealistic young people who thought the system could be reformed. (163)

THE GERMAN COURTROOM GETAWAY

Without guns, hacksaws, or hostages, three German radicals managed to liberate one of their number from the clutches of the "justice" system in the middle of a court hearing. The three were on trial for various charges. . . . Two of them, Michael "Bommi" Baumann and Thomas Weisbecker, were expecting to be released on parole, while the third, Georg von Rauch, was going to be sentenced to at least ten years in prison, when the court adjourned for an afternoon break. Thomas and Georg both had long hair and beards, and looked quite similar to each other in the unsophisticated eyes of the police and lawyers; so before reentering the courtroom Georg gave his spectacles to Thomas. When Thomas and Bommi were given parole and declared free to leave, Bommi and Georg leaped up and made quite a commotion, hugging and shaking hands with everyone and shouting. Both then quickly exited the building and disappeared, leaving Thomas, whom everyone had assumed was Georg. When the marshal came to lead Thomas away in chains, he protested that he had just been released on parole and the frustrated guards had to let him go, too. (173)

According to one legend, CrimethInc. began on a sunny morning in May when a future CrimethInc. worker (name withheld to protect the guilty) picked up hitchhiker Nadia C. on his way to work. The two found themselves in a conversation so intense that he drove right past his workplace and out into the country, where they took a long walk and continued talking. At the end of the walk he called his boss on his cellular phone, told him he quit, and then threw the phone into the lake by the side of the road. In the spirit of the moment the two decided to start a revolutionary organization then and there. (176)

Thus, the present has lost almost all significance for modern man. Instead he spends his life always planning for the future: he studies for a diploma, rather than for the pleasure of learning; he chooses his job for social status, wealth, and "security," rather than for joy; he saves his money for big purchases and vacation trips, rather than to buy his way out of wage slavery and into full time freedom. When he finds himself experiencing profound happiness with another human being, he tries to freeze that moment, to turn it into a permanent fixture (a contract), by marrying her. On Sundays he goes to church, where he is told to do good deeds in order to one day receive eternal salvation (as NietzsChe says, the good Christian still wants to be paid well), rather than for the sheer pleasure of helping others. The "aristocratic disregard for consequences," that ability to act for the sake of action that every hero possesses, is far beyond him. (196)

[Cartoon conversation:]

Margaret: So the firm I work for is really great. They have several big accounts right now. I'm just a secretary, but I'm hoping to advance. The boss likes my work. It's good to see you again, Beatrice. What do you do?

Beatrice: I write stories.

Margaret: A writer? That's great! Where do you work?

Beatrice: I work at a restaurant.

Margaret: But . . . you said you write stories.

Beatrice: I do. I also sew clothes, make necklaces for friends, and grow flowers in my garden, and play with my beautiful puppy Bartholomew.

Margaret: Oh, I see! Those are your hobbies. . . .

Beatrice: No. That's what I do.

[A two-panel pause; Margaret looks distressed.]

Beatrice: What do you do, Margaret?

[Another two-panels of pause; Margaret looks even more distressed; then, the sun breaks through the clouds.] (263)

|