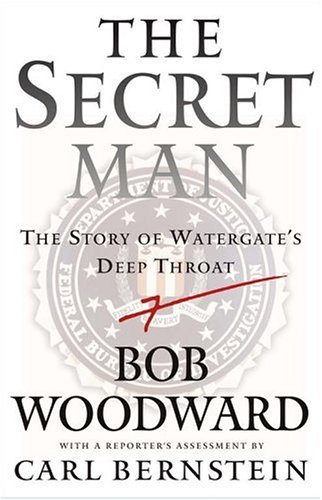

The Secret Man: The Story of Watergate's Deep Throat

Bob Woodward (2005)

I finally extracted information that he was an assistant director of the FBI in charge of the inspection division, an important post under Director J, Edgar Hoover. That meant he led teams of agents who went around to the FBI field offices to see if they were adhering to procedures and carrying out Hoover's orders. I later learned this was called the "goon squad." (20)

lt told me that after he had his law degree his first job had been with the Federal Trade Commission. This was the early 1940s, when he was in his late 20s. His first assignment was to determine for the FTC if toilet paper with the Red Cross brand name had an unfair competitive advantage because people thought it was endorsed or approved by the American Red Cross. People were resistant to questions about their toilet paper usage, he discovered, and he couldn't solve the case. The FTC was a classic federal bureaucracy, slow and leaden, and he hated it. (23)

But Felt goes to great lengths to put Hoover's career in the most positive light, pointing out that after Pearl Harbor, for example, Hoover was the one senior official who opposed the relocation and internment of Japanese-American citizens, In Felt's words, Hoover was "the one man of high rank in the federal government who sought to prevent this rape of the Constitution and of human rights."

Many people would find it laughable to see Hoover described as a defender of the Constitution and human rights. Yet in a long chapter on the Bureau's wiretapping of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. in the 1960s, Felt goes so far as to justify Hoover's actions and blames others including Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, who Felt says was worried about King's ties to a member of the Communist Party. The King investigation, according to Felt, "demonstrates the stresses and strains under which the FBI operated." Felt noted that in addition to telephone taps, "microphones were placed in various hotel and motel rooms occupied by Dr. King in his travels about the United States."

In Felt's telling, it is almost King's fault that Hoover had to learn the details of King's private life. "When the puritanical Director read the transcripts of the tapes disclosing what went on behind Dr. King's closed hotel doors," Felt wrote, "he was outraged by the drunken sexual orgies, including acts of perversion often involving several persons.

"What the tapes recorded was a running account of [King's] extramarital sex life. On his journey about the country in quest of civil rights, he had been visited in his hotel rooms by a parade of white females, and it was all there to be heard, right down to his outcries in the throes of passion. Frequently his male visitors joined in the festivities."

Felt writes approvingly of Hoover's campaign to discredit King because King was, in the director's eyes, a hypocrite who did not have the morality to head the civil rights movement. The ends justified the means. Using that information was permissible for a larger, worthy purpose, and a judgment that could be made outside the law. (42-3)

If the shooter [of Governor George Wallace] had any connection to Nixon, the Republicans or the White House-or merely had been a supporter-the implications could have been immense. More than a year later, Carl Bernstein and I would establish and publish a story saying that on the night of the shooting, Nixon aide Charles W. Colson ordered Howard Hunt to break into [would-be assassin Arthur] Bremer's apartment in Milwaukee to discover if Bremer had any connections to political groups, hopefully tying Bremer to left-wing politicians. (49)

This would have to be our last telephone conversation, he said angrily. He confirmed the cash payments to Magruder and Porter, indicating that the money flow was important. This later was reduced to the slogan "Follow the money," a phrase which as best I can recall he never used. For decades I had thought he used that precise phrase, but it is not in our book, All the President's Men, and I cannot find it in any of my notes. But that certainly was the idea. (70-1)

The memos I typed from our interviews had "X" at the top, or in one case, "M.F." It stood for my friend, but of course they were Mark Felt's initials, hardly first-rate tradecraft to protect his identity. (74)

After those weekend stories, the White House and Nixon campaign let loose on the Post. Bob Dole, the Republican national chairman, delivered a speech in which he devoted three pages to connecting our reporting with the campaign of Nixon's opponent, Senator George McGovern, the Democratic nominee for president. Dole (who many years later apologized to me) said that the Post was McGovern's "partner in mud slinging. . . . Mr. McGovern appears to have turned over the franchise for his media attack campaign to the editors of The Washington Post, who have shown themselves every bit as sure-footed along the low road of this campaign as their candidate." (83)

Haldeman reported that he had learned authoritatively from his own secret source, which he would not name for the president, that there was a leak in the FBI.

"Somebody next to Gray?" Nixon inquired.

"Mark Felt," Haldeman said.

"Now why the hell would he do that?" the president asked.

"You can't say anything about this, because it will screw up our source and there's a real concern. Mitchell is the only one that knows this and he feels very strongly that we better not do anything because—"

"Do anything?" Nixon interrupted, adding incredulously. "Never?"

"If we move on him," Haldeman warned, "he'll go out and unload everything. He knows everything that's to be known in the FBI. He has access to absolutely everything."

Haldeman reported that he had asked John Dean what to do about Felt. "He says you can't prosecute him, that he hasn't committed a crime. . . . Dean's concerned if you let him know now he'll go out and go on network television."

"You know what I'd do with him, the bastard," Nixon said. (85-6)

Of the Post, the president said, "We're going to screw them another way. They don't really realize how rough I can play. . . . But when I start, I will kill them. There's no question about it." (90)

[Felt] gave me a little lecture about breaking a conspiracy like Watergate. "You build convincingly from the outer edges in, you get ten times the evidence you need against the Hunts and Liddys. They feel hopelessly finished—they may not talk right away, but the grip is on them. Then you move up and do the same thing at the next level. If you shoot too high and miss, then everybody feels more secure. Lawyers work this way. I'm sure smart reporters must too." I recall he gave me a look as if to say I did not belong in that category of smart reporters. "You put the investigation back months. It puts everyone on the defensive—editors, FBI agents, everybody has to go into a crouch after this." (91)

Bradlee was reluctant to go with such a story, even though Deep Throat had said it was solid. He recalled how dangerous it was to anticipate high-level resignations. Back during the Johnson presidency, he said, Bill Moyers, a top Johnson aide, had been a source for a story that Johnson was going to replace J. Edgar Hoover at the FBI. Bradlee, who was the Washington bureau chief for Newsweek, had done a cover story saying the search for Hoover's successor is finally underway. The day Newsweek appeared on the stands, Johnson called a press conference. Just before, Johnson told Bill Moyers, ''you call up Ben Bradlee and tell him, 'Fuck you.''' Johnson then went out and announced that he had appointed Hoover the director for life. For years, Bradlee said, people blamed him for Hoover's lifetime appointment.

We held the story about Haldeman and Dean. (95-6)

That mid-May meeting took place in this context. It was the strangest and most alarming meeting. Felt was nervous, his jaw quivered. He raced through a series of statements and it was clear that a transformation had taken place.

First, he said, everyone's life is in danger and electronic "surveillance was going on—the CIA was doing it. He said that President Nixon had personally threatened Dean. The continued effort to buy the silence of Hunt, Liddy and the five Watergate burglars, the cover-up costs, was going to be about $1 million. Most alarmingly, he said that covert activities were going on that involved the entire U.S. intelIigence community.

After rattling all this off, Felt said, "That's the situation. I must go this second. You can understand. Be—well, I'll say it—be cautious." He indicated that he would soon be announcing his retirement from the FBI, and planned to leave the next month. (98-9)

With Felt out of the FBI, I figured he would not be up-to-date. But in the first week in November 1973 I contacted him in order to set up a meeting In the underground garage.

It was brief. He had retired from the Bureau, but he was in touch with many friends there. That's the way the place worked. He had one simple message: One or more of the Nixon tapes contained deliberate erasures. (102-3)

Felt was increasingly contemptuous of the Nixon White House and its efforts to manipulate the FBI for political reasons. The young, eager-beaver patrol of White House underlings—best exemplified by John Dean—were odious to him. Felt wore a so-called Page Boy, a tiny radio receiver which emitted a high-pitched whistle when he was off duty and had to call headquarters. Often, he found, it was a call to answer some routine question from Dean or some underling. Most notorious was Lawrence Higby, Haldeman's administrative assistant, who passed on his boss's every request as if the outcome of civilization was in jeopardy if something was not done at once. Higby was so efficient that administrative assistants were known as "Higbys." At one point Higby even had his own Higby—"Higby's Higby." Higby rankled Felt particularly. (105)

Felt published his book, The FBI Pyramid, in 1979, before his trial. The inside flap said, "Mark Felt, who was ":rumored to be the famous informer Deep Throat ... "

How odd, I thought, that he would allow himself to be identified "rumored to be the famous informer," and then to categorically deny it in the book. (139)

Wednesday, October 29,1980, was an extraordinary day in the trial. As the Post reporter, Laura A. Kiernan, wrote, the 67-year-old witness had a familiar face and hair, a "powdered ghostly look."

After taking the oath swearing to tell the whole truth, the witness sat down and said he was retired.

"Were you once the president of the United States?" the prosecutor inquired.

"Yes," said Nixon. He had been called by the prosecutors. Nixon had volunteered to appear—the first and only time he would testify in a trial after resigning. . . .

It was a maddening 45 minutes of testimony because Nixon was not asked whether he had approved the five break-ins that Felt and Ed Miller authorized. He seemed to side with Felt, because as president he believed he had authority to order break-ins if the national security was "threatened and he had delegated that authority to the FBI director. Though Huston had said in a memo to the president that the "black-bag jobs" were "clearly illegal," Nixon said that the good cause of protecting the national security overrode such considerations. A presidential authorization, Nixon claimed, meant that "what would otherwise be unlawful or illegal becomes legal."

This was the very attitude that got Nixon in trouble on Watergate, and he made these declarations pounding his finger on the wooden bench in front of him. (141-2)

He could recall nothing about the flowerpot, nothing about my marked New York Times, nothing about the Roslyn underground parking garage. Did he recall being my source, the one that was called Deep Throat?

He said he didn't know.

Had he read All the President's Men? Seen the movie? Did he recognize his role, what he had done, how he had helped us, taken supreme risks to his career, put everything in jeopardy?

He didn't remember, he said, carefully noting that that didn't mean it hadn't happened.

Maybe it was the wine, maybe he didn't remember, maybe didn't wish to remember. Maybe the denial was so embedded in his persona, his way of life, that he couldn't or didn't want to unlock it. (174)

Repeatedly, those I had interviewed for my books or stories for the Post had cited my willingness to protect a source such as Deep Throat for nearly 30 years as a reason they were willing to talk about some of the most sensitive and Top Secret deliberations in the U.S. government. "You'll protect sources," was a common refrain, often delivered with a knowing chuckle or a direct or indirect reference to Deep Throat.

I would even say at times that this was a "Deep Throat" conversation, and some of those in the most sensitive positions or best-placed crossroads of the American government would nod and then talk in remarkable detail, plowing through security classifications and other barriers as if they did not exist, including private conversations with a president. Deep Throat, or the concept of rigid source protection, became the unstated part of the conversation. (184)

The Deep Throat legacy was a foundation of establishing the compact: I would never tell. Often during the first interviews, subjects would start talking almost at once. In an odd way, many, or certainly some, wanted to deliver the goods, the secrets. The transaction with the reporter was important, not only for the reporter but also for them.

I did not want to do anything to jeopardize this legacy or advantage. The opportunities for the future were more important than disclosing Deep Throat's identity. (185)

Mark Jr. had a stunning message about his dad. "He has told us for the first time in all these years that he was Deep Throat." (194)

I had obtained a copy of the transcript for my book Shadow: Five Presidents and the Legacy of Watergate. It was painful reading. Reagan couldn't recall if George Shultz had been his secretary of state or Ed Meese his counselor, both of whom were among his longtime friends and associates. Reagan was read portions of his own diary, and he said something I'll never forget: "It's like I wasn't president at all."

Very sad. As I reflected about this I was sure that I didn't want to badger Mark Felt in the same manner. I didn't want Felt to have to say, in effect, "It's like I wasn't Deep Throat at all." (198)

It was the Nixon administration that presented the most serious challenge to the Bureau, because it was an attempted takeover from the top. The installation of Pat Gray as director threatened the institution. So the FBI was at war, though not with the usual suspects. The war was with Nixon and his men. So Felt took to the underground parking garage. He never really voiced pure, raw outrage to me about Watergate or what it represented. The crimes and abuses were background music. Nixon was trying to subvert not only the law but the Bureau. So Watergate became Felt's instrument to re-assert the Bureau's independence and thus its supremacy. In the end, the Bureau was damaged, seriously but not permanently, while Nixon lost much more, maybe everything—the presidency, power, and whatever moral authority he might have had. He was disgraced.

By surviving and enduring his hidden life, in contrast and in his own way, Mark Felt won. (214-15)

|