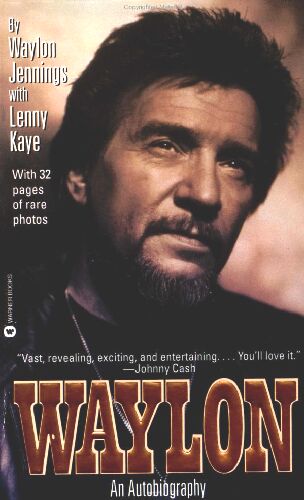

Waylon: An Autobiography

Waylon Jennings with Lenny Kaye - (1998)

They'd met at a dance. William Albert Jennings and Lorene Beatrice Shipley. He was a musician in a one-man band, just him playing harmonica and guitar. She couldn't have been more than fourteen, from Love County, Oklahoma. She danced every dance. Momma used to get mad because Daddy didn't know how to dance, and she'd have to hold the harmonica for him in his mouth—they didn't have holders in those days—and wouldn't get to dance every set. (4-5)

So it came down to Wayland Arnold. But when a Baptist preacher stopped by to visit Momma, he said. "Oh. I see you've named your son after our wonderful Wayland College in Plainview," so she immediately changed the spelling to Waylon. We were solidly Church of Christ, saved by baptism instead of faith. She never got around to switching it on the birth certificate. I still hate my middle name and for a while I didn't like Waylon. It sounded so corny and hillbilly, but it's been good to me, and I'm pretty well at peace with it now. (6-7)

When you're born in Texas, you think that you are a little bit taller, a little bit smarter, and a little bit tougher than anybody else. It's a country unto itself, it really is. In fact, it was the only place that was a country before it was a state, and the people who live there still feel that way. My wife, Jessi, hit it right on the head when she said ''They think the rest of the world is overseas." Of course, she's from Arizona. She knows what it's like being around cowboys. (7)

The last time I was pulling cotton I was about sixteen. I said, "I didn't plant this shit, and I ain't never gonna pull it up no more." And I quit. I left that sack sitting right there. It may still be there to this day, as far as I know. (8)

There were two kinds of people Grandpa didn't trust, a preacher and a cop. He'd say "They both think they're sanctified in everything they do." (9)

Let me get this right now. If I don't, I could get shot by some relatives. My great-grandfather West married a woman who already had a daughter about twelve years old. He had another child by this woman, whoever she was, which was my grandmother. Now my grandmother had a sister, right? We thought that my grandmother's mother had died, but we found out later that wasn't true. She had run off and left both kids with him. So he married the original daughter, which made my grandmother's sister her stepmother. (10)

Years later I took him up to see her in an old folks home in Lubbock. He stayed with her, and I went and did my business and then came and picked him up. On the way back, he was sitting real quiet, staring out the window. All of a sudden he blew his nose and you could see he'd been crying. "When I was young, there wasn't a handsomer woman alive," he said. "You never know how things are gonna turn out." (11)

We had to ride in the back of the truck out to Grandpa Jennings's place, no end gate to it and just a tarp flapping. We'd ride in the back of that truck all day long; they didn't go that fast then. If you fell out of one it wouldn't hardly hurt. You could run and catch up with it. (12)

Grandpa Jennings never let anything bother him. He thought no matter how bad it might look today, it' d probably be all right tomorrow. (12)

Grandma Tempe would keep the butterbeans going for at least two days. (12)

Grandma Jennings was stern woman. I can still hear her muttering "nasty nasty nasty" every time she'd catch us talking about girls. In later years, after l'd have sex, it seemed like someone ought to come up and shake their finger at me, saying "nasty nasty nasty." (12-13)

Of all the religions I've run into, the Church of Christ has probably got it wronger than anybody. They're self-righteous, narrow-minded. and truly believe they're the only ones going to Heaven. If you don't believe the way we do, they say, you're going to go straight to hellfire and damnation. With a side order of brimstone. (13)

Their concept of God was of a Father who told His offspring, "I created you, but I'm not going to be there ever. You're not going to see me or hear my voice and I'm going to give you a book that is not easy to read at all, it's hard to understand, but you are not to question it. It's a sin to question it. If you don't follow my words, and do everything that book says, even though you're my child and I love you, and I'm your Father, I will throw you into a lake of fire and you will burn eternally and I'll hear you scream for the rest of eternity."

That's what the Church of Christ teaches, and it's not my concept of believing. If God knows yesterday, today, and tomorrow, why would He cause us so much misery in this world? I don't think God would destroy the earth and let Satan live again. Or blame us for the Forbidden Fruit. (14)

I thought, man, I'm going to hell, 'cause everything they tell me is a big sin is something I like. A lot. (15)

Daddy took cotton sacks and hung them in the back where we'd keep the chickens, and we'd go in there with a light and hold up the eggs. Sometimes you would see a bloody speck, and that was a number two; and number threes were cracked. Number ones didn't have anything wrong with them. All the bakeries in town bought the number twos or number threes, and I always thought of that every time I wouId eat a doughnut. (23)

I drove them old farmers nuts, trying to learn to play the guitar in the back room. I'd sit on an old feed sack, pounding away. and every once in a while one of them would come in the back, snuff rolling down his face, saying "If you're playing that ol' guitar in parts, well, leave my part out. 'Cause you ain't worth a shit. I know that ol' Bob Wills, and he ain't nothing but an old alky-holic. Anybody who plays that ol' guitar they won't never amount to a hill of beans, and you'll just be an old alky-holic." (23-4)

I didn't even consider New Mexico to be the West. Arizona was the West to me. (24)

Lash came to our town on a guest appearance in the late forties , and I was right in the front row. He was going to do his act onstage, and they were also going to show some of his movies. The Palace had a small stage, maybe twenty feet wide at most, and he was in the middle of his whip act, guns and all. He missed and whipped the screen, and ripped it.

When the lights came back on and the cartoons started, I went out to the lobby to get a drink of water. There stood Lash Larue. He was having it out with Bill Chesire, who owned theater, and Truitt Benson, the manager. Lash still had his gun on, was carrying his whip, and had his hat cocked over.

"You're going to pay for the screen," they were telling him.

"I told you the stage was too short," he said. "I told you it was dangerous, even for my assistant. You should've had insurance."

They said, "You're going to pay for it."

Lash looked them straight in the eye. "I got a gun and whip that says I won't."

I looked around and thought, I'm the only one that ever heard that. I bet God wasn't even listening. From then on, if I was playing cowboys out on the prairie, no matter who I was supposed to be, somewhere in my dialogue I had "I got a gun and a whip that says I won't." (25-6)

I was probably more like a mule than a horse. There was something about mules that I liked. They're strong—I could lift a hundred-pound sack of feed down at the Produce—and hard-working, but they're stubborn sonofabitches. If a job was too big or wrong for them, they'd know it. A horse would pull till it injured itself, but a mule wouldn't do that. (31)

I was expelled from music class in high school for "lack of musical ability." If they wanted a B flat, they'd just hand me a B and I'd flatten it. I never learned to read music. (33)

You had to drive by the sewer to get to Spade. Ask one of the spit-and-whittle crew how to find it, they'd say "You just go out the Lubbock Highway till you smell shit and turn left." (37)

For the first year, all Maxine really gave me was the stone-aches, bad. After I'd drop her off at the house, I'd be doubled over, having to walk spraggle-Iegged from where I'd kissed her goodnight. I couldn't wait to get out of sight. The only way I could relieve myself after one of our hot dates was to hop out of the car, go around the front and grab the bumper, spread out my legs, and strain real hard to lift it off the ground. (38)

I couldn't even figure out how late she was. I never thought about abandoning her. Hell, I'd already committed the ultimate sin from the way I was raised. We went ahead and got married, and on our wedding night, she started her period. That's old country boy luck for you. (39)

I knew I would be leaving Littlefield soon. It was just a matter of time. I always figured in the back of my mind that people divide themselves in two: the ones who don't know it's out there and those who know there's something somewhere else. (41)

It was like I saw a black cat running across my path and I pulled my handkerchief out and chewed the corner off of it to kill the bad luck. That cat was my lifeline if I stayed in Littlefield, and the handkerchief was my guitar. My singing did the chewing. (41)

"What if," I asked my dad one day somewhere in the early 1950s, "they mixed black music with the white music? Country music and blues?"

"That might be something," Daddy replied, and went back to pulling transmissions. (44)

Buddy [Holly] cut the song, and after he left, Norman [Petty] took the singing group he used for backing vocals, had them go "dum diddy dum dum, oh boy," and took a piece of the writing credit. He was really good at that. He took part of all of Buddy's songs and hardly paid him any performance royalties. He kept a tight control on the Crickets' money. (55)

I had never played bass before. I didn't even know till about a week after I was on tour that it was the same as the top four strings of a guitar, only an octave lower. It ruined my whole style of playing when I realized. I had memorized everything from the records. (57-8)

Me and Goose walked around for two days in a row looking for the Empire State Building, and we were standing right under it. (59)

The next thing I know, Buddy sends me over to get a coupIe of hot dogs. He's sitting there in a cane-bottomed chair, and he's leaned back against the wall. And he's laughing.

"Ah," he said. "You're not going with me tonight, huh? Did you chicken out?"

I said no, I wasn't scared. The Big Bopper just wanted to go.

"Well," he said, grinning, "I hope your damned bus freezes up again."

I said, "Well, I hope your ol' plane crashes."

That took me a lot of years to get over. I was just a kid, barely twenty-one. I was about halfway superstitious, like all Southern people, scared of the devil and scared of God equally.

I was afraid somebody was going to find out I said that, and blame me. I knew I said that. I remember Buddy laughing and then heading out for the airport after the show. I was certain I caused it. (69-70)

I've often wondered if Buddy wasn't flying that plane. Every time we'd go in a plane in West Texas, the minute we got off the ground, he'd say "Let me take the wheel." That young pilot—who's going to say no to Buddy Holly? (71)

Maxine's dad got real sick, and we went out there to see him. He lived in Scottsdale, and her sister lived in Coolidge. It was the first time I'd been that far west, and it took hold of me.

You look at the mountains, and you don't know if they're Indian or cowboy. The desert is still and strong. You ain't got a chance. You can't push it back. You just surrender to the surroundings. When I got there, it was like I stopped pushing toward something and just let myself go, floating where the winds would carry me. I felt lonesome.

You gain strength from the environment; you don't try to destroy it. It was like I passed through myself, and all of a sudden I came out of the desert into Phoenix, nestled in the VaIley of the Sun, all palm trees and shadows. It was beautiful. (81)

I was having a little better luck in Coolidge, Arizona, where Maxine and I stayed with her sister. There was a guy named Earl Perrin that was buying a bunch of radio stations and tying together what amounted to an Arizona network out of them. In 1960, that was ahead of its time. I was playing at a place called the Galloping Goose with a pair of local boys, Billy Joe Stevens and Claude Henry. I was big-time when they found out I had been with Buddy Holly. I probably made as much as they did, which was fifteen dollars a night. (82)

Maxine didn't like living in Coolidge. She wanted to go back to Texas. She didn't want to clean house. I think the only thing she liked was fighting with me. (85)

I moved back to Coolidge and got a job in a place called the Sand and Sage Bar [sic; Sage and Sand (now all gone but the neon sign out front)], until a better gig came along in Phoenix at a steak house named Wild Bill's. I'd drive back and forth every two or three nights. (86)

Maxine had had her fill of life in Coolidge. She was going to force my hand: "I don't like it here, I'm leaving, and I'm taking the kids and going to Texas." By then, baby Deana was on the way. (87)

I was back to playing music. "Wild Bill" Byrd fired me—he was notorious for giving bands the heave-ho—and I moved over to Frankie's, an old bar that could hold about ninety people, over on Thomas Road in the center of town. (87)

Wild Bill fired us again, and we got picked up by the Cross Keys, which had been a jazz club, out at the corner of Scottsdale Road and Camelback. It was a strange place to have a nightclub, a retail area in "exclusive" Fashion Square right across the street from Goldwater's Department Store. It was one of a string the family built into a fortune that launched Barry's political career. The Cross Keys was smaller and not as well known as Wild Bill's, but the owner was able to give a better deal. My crowd was starting to follow me. I kept the bar-hoppers and the cowboys, and added the up-and-coming professionals, among whom were baseball players spring training in the Cactus League, like Tony Conigliaro.

Two building contractors dropped in one Saturday, saw the place was wall-to-wall people, and started coming around. They liked my music a lot. They were about to build a club for a man named Jimmy D. Musiel, who had a part ownership in another place crosstown called Magoo's. He'd had a business falling out, and his ex-partner, Bob Sikora, kept Magoo's. J.D. hired these old boys to build him a double-decker club on Rural Road, just over the Tempe line, down in the River Bottom district. There was to be music both upstairs and downstairs; downstairs capacity would be about three hundred, but upstairs they could fit more than four times that many. J.D. said if I signed a contract to play regurarlee, regularily, uh, regulee, then he'd design the club around me.

I chose to play upstairs. I helped design the stage and get the sound system together, though then if you had one microphone for singing and another for background vocals, you had more than most. There was a beautiful dance floor in front of the bandstand, and a long bar running the length of the opposite wall, ninety feet from one end to the other. Downstairs, the River Bottom Room, was rock 'n' roll, booked by J.D.'s son, Jimmy Jr., and everyone from the Grass Roots to Bill Haley and the Comets played there, accompanied by shimmying go-go girls.

J.D.'s was automatically a smash. People were trying to get in that club every night of the week. I was the honcho and it put me on the map. (89-90)

We were right by Arizona State University, and the students started coming around. All the other bands in town were western swing. We played all kinds of songs; I didn't just sing country music. We did rock 'n' roll and some folk music and some blues. We played things the cowboys liked as well as the students, the professors, the baseball players, and the rock 'n' rollers. Everybody got along, which is how I started to realize that music can be a common denominator that draws people together. If they let it. (91)

Richie was my right hand. Wiry and sharp-featured, he had been born in Bradley, Oklahoma, and grew up in Bagdad, Arizona. Bagdad is an open pit mine, is what it amounts to. (91)

In July 9, 1963, a contract arrived at 2022 North Thirty-sixth street, apartment B1, in Phoenix, giving me a 5 percent royalty rate for two sides of a single: "Love Denied" and Rave On." The flip was the Buddy Holly song, while Bill Tilghman wrote "Love Denied." It had a real high ending, almost like Roy Orbison. I think that was one of the things Herb [Alpert] and Jerry [Moss] were impressed with, my range. (95)

Herb kept looking for something in me he couldn't find. It just wasn't there, really. He truly liked my singing, and he wanted me to make it, but even if you get a bigger hammer, you can't fit a round peg into a square hole. One night we tried "Unchained Melody" countless times. I never understood, though I do now, what he was talking about. It was too far over my head. The only word that matters in that song is "hunger"; if you get that right, the song is yours. I never got it. (95)

In the fall of 1964, I went into Audio Recorders in Phoenix, a studio owned by Floyd Ramsey, where Duane Eddy had done his earliest singles. (96)

I was living on North Thirty-sixth Street in Phoenix when Kennedy was assassinated. I was there the first time I ever heard the Beatles over the radio. It was the first nice place I'd ever had. (97)

Lynne knew how to take care of money, and we were getting ahead. She had come from Pike County, Kentucky, where her dad had been a moonshiner. He had to move the family out to Idaho when Lynne was little, and he hadn't been there too long when he was hit by a car going across the street in the little town of Chubbock. The feds came and dug up his body to make sure it was him. He must've done something pretty wrong back in Kentucky for them to go to all that trouble. (97)

We were doing quite well. At J.D.'s I was taking home over a thousand dollars a week, and I was able to buy the first brand-new car I had ever owned, a '64 Chevrolet. As a family, we moved over to Pierce Street, and then got a house in Scottsdale, on East Amelia right off Indian School Road. (99)

When I look down today at my guitar, caught in the spotlights of whatever town is giving me a place on their stage, it's essentially similar to the instrument I played at J.D.'s. It's a Fender Telecaster; solid body, maple neck. It ain't got but two knobs on it. You turn it on and you have the same sound all the way through.

You can put a guitar against you and feel it vibrating as you play it. They're never really in tune, especially the B string. I hate the B string. What you learn to do is pull ' em into place with your finger. For me, they're a lot like women. You can touch one of them in the dark and know she ain't yours; or you're with the right one. (105)

Herb [Alpert] offered me a percentage of the company [A & M Records] if I would stay. It was the hardest thing in the world to say, "No, I want to try this." They were the best people for giving me my release, and still are. (105-6)

I'd thought long and hard about leaving Phoenix, even asking another RCA artist passing through town what he thought of moving. His name was Willie Nelson, and he'd been having success as a songwriter. "Crazy," and "Funny How Time Slips Away," for Patsy Cline, were already standards, and Faron Young's "Hello Walls" was on its way to becoming a classic. He was a fellow Texan playing across town at the Riverside Ballroom. We had never met before, but my first album was about to come out, and he'd also just gotten his start recording as an artist in his own right. He liked my singing and I liked his.

Willie came to town and sent word he wanted to meet me. I went over to the Adams Hotel and spent the afternoon finding out how much we had in common, asking him about Nashville and what I might expect. He had just moved there. I told him I had a good deal at J.D.'s. By then, I was pulling maybe fifteen hundred dollars a week, clear. Not bad for a "sit-down" job, as we called gigs that you didn't have to go on the road for.

"Don't move," he told me. "And if you do, let me have that job!"

As usual, I followed the opposite course. (108)

We went back to performing in Phoenix. Though it wasn't the megalopolis it is today, I was a big frog in a not-much-bigger puddle. The entertainment columnist at the local paper kept referring to me as "That Guy down at the River Bottom." He couldn't bring himself to say my name. People knew I was going to leave, and that only fIlled up J.D.'s even more. (109)

People were happy for me; but there were a lot of people crying in their beer because I wasn't going to be theirs any more. I kind of missed that part myself. Wish me luck; and this one's a ladies' choice. (110)

And by booking you so far in the future, it might backfire, as Little Jimmy Dickens found out when he scored a major pop hit with "May the Bird of Paradise Fly Up Your Nose." He couldn't break out of the low-ball contracts he had signed a year in advance. By the time he was able to book new shows at a bigger figure, the Bird of Paradise had flown up his ass. (112-13)

For Chet, a smile meant "that sounds pretty good." A grin was wonderful out of him in the studio. If he said "Man, I liked that," it was probably going to be a number-one record. I often fantasized about being out in the studio recording, and Chet getting up in the control room, standing on top of the console, jumping through the plate-glass window, rising up, wiping the blood off and yelling "Goddamn, that is a smash!" (134)

. . . or piano players like Floyd Cramer or Hargus "Pig" Robbins. I always thought you could've had a piano player that owned the world if he'd have had Pig's left hand and Floyd's right. (135)

I just did what felt good to me. It was like Grady Martin said when they asked him if he read music. "Not enough to hurt my playing," he replied. The truth is I never understood that much about the mechanics of music. I'd come in wrong, and I'd turn the beat sideways. I was the only guy in the world who could hum out of meter. My guitar playing came from inspiration only. I did it out of self-preservation. I could never stand to practice. Everything I know I learned in front of an audience. Whenever I'd pick up a guitar, I'd start to play a song. (163)

One of our first dates was out to the Navajo Indian Reservation in Tuba City, Arizona. There's nothing there, only the painted desert and two or three roads in the whole northeast corner of the state, each following an endless straight line that goes like an arrow until it hits the vanishing point. (165)

I was just wobbling around, on pills and drunk. Merle Haggard and his manager, Fuzzy Owens, got me in a poker game and cleaned me out. I had four or five thousand dollars on me, and they won everything. They were there to get my money. That was it. I think Merle is a great singer and songwriter, and probably he was in as bad a shape as I was, but we've never been close since that night. I can still remember their faces. When I was broke, they said their good-byes and left. I never forgot that. (173)

I'd eaten some pie and drank some milk in a little cafe near the Colorado border of the Ute reservation. That night I witnessed the damnedest sight I ever saw in my life. A cop whose hobby was beating up Indians put on his gloves and waded into a crowd at a bar. There he was with his burr haircut, in his glory, pushing and punching them toward the door, and outside they were beating his car all to hell; there wasn't one place that wasn't dented. (181)

WGJ Productions. It had a nice ring to it. Waylon Goddamn Jennings Productions.

Free at last. (192)

Finally, I'd had enough. I moved the sessions to Tompall Glaser's studios at 916 Nineteenth Avenue South, nicknamed Hillbilly Central. RCA protested mightily, but I told them this was the way it was going to be from now on.

That's all you got," was about the way I put it. Lash Larue would've been proud of me.

RCA had no choice. "We can't release this," they told me. They had a contract with the engineer's union that all their recording was to be done in-house, that RCA records could not release any record that wasn't cut with an RCA engineer, and that RCA artists had to use RCA studios whenever they were within a two-hundred-mile radius of Nashville. Jerry Bradley even went to Washington to get a waiver for one album, but the union wouldn't go for it. In the face of my stubborn refusal, RCA bit the bullet. They shipped the record and violated their contract with the union. That broke the whole system's back. (193)

I hooked up with Tompall over a pinball machine. . . . We could spend a thousand dollars a night, a quarter at a time. Tompall could stay up as long as I could. Bobby Bare had three machines in his office, and when they were filled, or he closed for the day, we'd go all over town looking for pinballs, out Route 65 to a truck stop south of Nashville, down Dixon Road, then a grocery store a couple blocks from Tompall's offices. When we found one we liked, we practically moved in. One night at the Burger Boy, Tompall was playing a certain machine he liked up front, but he wanted to be by me in the back room, so he dragged his pinballs up the steps and planted it next to mine. The owner just watched open-mouthed, though he didn't say anything because we were probably paying his rent and more. Even after J.J.'s officially shut for the night, the clerk would sleep on the counter, waking up every now and then to change a hundred dollar bill for quarters. (195)

It was like a marathon. You could stand there, pumping quarters in, and get lost in your own thoughts, idling in neutral. You'd unwind so much that it was hard to stop and do something else. Sometimes we'd be at the machines for two or three days, waiting for the six card to fall into place. Tompall once kept track of our spending, thinking he could take it off his income tax. At the end of the year, he'd spent thirty-five thousand dollars on pinballs. (196)

He might've continued scuffling had not a sawmill accident clipped four fingers of his right hand and turned him into a songwriter. Billy always had a sense of humor about it, though. He was sitting on a bed one time playing guitar, and a guy who worked for me came in and said "Billy Joe, if you don't mind me asking, what happened to your fingers?" Billy started glancing around and digging in his pocket. "Damn," he said. "They were here just awhile ago." (201)

[Billy Joe Shaver] tried to call me when I got back to Nashville, but I was always in a meeting or on another call or "not in." This went on for months. . . .

He caught up with me one night at RCA recording. . . . .. I got these songs," he said, "and if you don't listen to them, I'm going to kick your ass right here in front of everybody."

He could've been killed there and then by some of my friends lining the walls, but I took Billy Joe in a back room and said "Hoss, you don't do things like that. I'm going to listen to one song, and if it ain't no good, I'm telling you goodbye. We ain't never going to talk again."

Billy played me "Old Five and Dimers," and then kept on going. He had a whole sackful of songs, and by the time he was out of breath, I wanted to record all of them. (201-2)

If there ever was a free spirit on Earth, it's Willie Nelson. He'll tell you it's because his philosophy of life is "follow your intuition."

It's just that we go about it in different ways. Willie does not want to break the natural flow of things. He does not want confrontation. Whatever's bound to happen, he figures, go ahead and let it. Willie would sooner bend than break, leaning backward until he throws you off balance and gets his way.

With me, there's no gray area. It's all black and white. I'm in my element when I'm fighting for something. I'll stand right out there in the dirt and take on everybody in town for his and my right to believe in whatever we think is worth caring about. And if a truck is coming and I've got my back turned, you better holler and not let it run over me, natural flow be damned.

When Nashville started giving us both a hard time, Willie up and left for Texas. He didn't go back. I stayed in Nashville. I guess in the end we both survived as best we knew how, and came out on the other side with our pride and music intact.

He'll never change, and I don't think he should. He'll give you everything, say yes to anybody, trust that events will turn out fine in the end. He'll never be rich. He loves to be a gypsy on the road, playing that beat-up ol' guitar, wearing that silly-ass headband, singing through the side of his nose and signing autographs after the show, which is where his concept of karma comes in. He thinks you should be thankful if Miss Fortune helps reimburse you for a deed from another life.

I say, "Willie, I believe that what goes around comes round in this life, but I wasn't with you in the other ones. You better leave me out of this."

He never does, though, and I've had to start my life over several times because of him. If he'd ask, I'd do it all over again. He's my personal Willie, and I'm his Waylon. Yin and yang. Where there's a Will, there's a Way. (205-6)

Willie was like a god in Texas. People there think when they die they're going to Willie's house. (206)

He returned to Texas, settling in Austin, where he felt an affinity with the redneck hippie community centered around a converted armory named Armadillo World Headquarters. In those days, the combining of those two worlds was a big deal: long hair, pot smoking, and youth didn't set well with country music or its truck stop audience.

Willie helped bring all that together, or did all that bring Willie together? Pretty soon he was growing his hair long and playing in front of whooping crowds at the Armadillo Headquarters, calling me up and telling me I should come visit this little nightclub in Austin. (206-7)

The Armadillo crowd was all young kids, longhairs, sitting on the floor. The smell of reefer hung heavy in the room. I thought about my head in the mouth of a lion.

I was upset. "Somebody find that red-headed bastard and get him here," I said. When Willie arrived, all smiles, I tore into him. "What the hell have you got me into?"

"Just trust me," he said.

I said, "I know what that means in Hollywood, but it better not mean the same thing here."

I didn't have to worry. They went nuts when I hit the stage, and even crazier when Willie came out to join me.

It was a new way of thinking. We were going against the grain, and yet we weren't alone in how we felt. Willie saw there were two streams of country music, moving parallel, sometimes further apart, sometimes growing closer. Each was just a little afraid of the other, and he wanted to bring them together.

What better way than to have a Picnic? Though modeled on Woodstock, Dripping Springs took on a character all its own as it grew, the old and the new together. (207-8)

Our vision of country music didn't have any shackles attached to it. We never said that we couldn't do something because it would sound like a pop record, or it would be too rock and roll. We weren't worried that country music would lose its identity, because we had faith in its future and character.

In trying to broaden its appeal, country music had gotten safe and conservative. Awash in strings, crooning and mooning and juneing, Countrypolitan may have been Nashville's way of broadening its pop horizons, but it was making for noncontroversial, watered-down, dull music that soothed rather than stirred the emotions. It had honey dripped all over it. (209)

We could roar the cars up to the metal back door, climb the back stairs and hang out. One night I rear-ended my Cadillac into Tompall's Lincoln Continental Mark IV. When I went in, he office, I said, "Tompall, who's just given you a brand new Ovation guitar?"

"You did, Waylon," he answered.

''Tompall, who's the best friend you've got in the world?"

"You are, Waylon."

"Tompall, who stands behind you when nobody else will?"

"You do, Waylon."

"Tompall, who just backed into your Lincoln Continental?"

He chased me down the hall, through the space where the door that I sawed in half and nailed over Tompall's window used to be. Why'd I do it? It got in my way. (213-14)

Dreaming My Dreams is my favorite album I've ever done. (221)

[In New York:] "My name is Waylon Jennings," I said before we started. "We're all from Nashville, Tennessee, and we play country music. We hope you like it. If you do, I want you to tell everybody you know how much you like it. If you don't like it don't say anything mean about it, because if you ever come to Nashville, we'll kick your ass." (224)

Neil's biggest move was to get me on a bill with the Grateful Dead at Kezar Stadium. With all the overhype, it was a breakthrough to play on the home field of Haight-Ashbury High, even though Janis Joplin had shown that it was a quick hitchhike between Austin and San Francisco. Musically it didn't work. Deadheads don't care if it's Jesus Christ up there. All they've come to see is the Dead. I felt older than them; when I walked out, I probably looked like that sonofabitch who'd told them if they weren't in by eleven o'clock he was going to ground them. My kids were old enough to be among that crowd. (224-5)

Willie and I were in the same boat. Neil was paddling it, and as much as he had to fight for me he had to keep Willie bailed out. I thought for a while he'd never leave Texas, but pretty soon his sense of an alternative country scene began to take hold, and Willie started becoming a genuine superstar.

He had shifted to CBS from Atlantic, where his first concept album, Phases and Stages, had concerned a marital breakup from the viewpoint of the wife. Willie could sympathize with that. He was a travelin' man, and he never hid the fact that he would rather be out playing than home every night. His first love was always the road. Everything else played second fiddle. He didn't mean to be a bad guy. At least, he figured, his wives got to be in the string section. (225)

As for Jennifer, she was a dear sweetheart. We were thick as mud. For a while, it wasn't easy. I could tell she loved me, but she felt guilty about it. We'd be playing and laughing and hugging, and all of a sudden she'd say "I hate you. I don't want to play."

Finally, I had to call Duane [Eddy], her father, and tell him that I respected his friendship, but that Jennifer was so loyal to him that she believed she couldn't have feelings for both of us. "I want you to know that I will never allow anybody to say anything bad about you in front of her, and you have to tell her it's okay to love me, too." From then on, she called him Daddy Duane and me Daddy Waylon. (228-9)

People would ask me how I felt about "I'm Not Lisa" going gold. Did I mind?

Mind? Jessi [Colter] was so happy, getting checks and buying presents for everybody she loves. For me, she put the down payment on our house, Southern Comfort.

But they'd continue: You've been struggling all these years, and here comes Jessi, first album, no reputation, and she has a million-selling record right out of the chute.

"Being a fuckin' legend," I'd have to say, "I don't give a shit." (230-1)

Now they [the Country Music Association] needed me again, because I was up for Best Male Vocalist, Song of the Year ("I'm a Ramblin' Man"), Album of the Year, and Entertainer of the Year. As I walked in with Jessi, scratching at my tuxedo, her telling me I should have hit them, Neil came over to me. "You won Male Vocalist," he whispered. "Jessi didn't win anything."

So much for secrecy. If nobody's supposed to know the awards before they opened the envelope, how did word get around? My heart went out to Jessi, and though my first instinct was to get the hell gone, I thought that maybe by staying I could raise some of the larger problems that faced country music, such as its closed mindedness and suspicion of change.

When it came time for Best Male Vocalist, Tanya Tucker and Tammy Wynette made a great show of opening the winner's envelope. I tried to be nice in my acceptance speech, thanking everybody for their support, though I knew that block voting and mass trading between the big companies—we'll give you two hundred votes for your artist if you give your four hundred votes to our writer—probably had more to do with it than anything else.

At least Glen Campbell, the host, was happy. "All I can say, Waylon, is it's about damn time." Predictably, the CMA got a few letters protesting Glen's use of profanity.

I was happier watching Charlie Rich get drunk and burn up the Entertainer of the Year award, holding a cigarette lighter to the envelope, please. They went to grab him, but when Charlie was drunk, it was best to stay out of his way. . . .

Oh, yeah. John Denver won Entertainer of the Year. Now that's what I call country. (231-2)

Chapter 8: This Outlaw Shit (233)

One night in Atlanta, some guy yelled at me, ''Take that damn hat off, shave that face and do 'Waltz Across Texas.' "

I said, "You come around after the show and I'll waltz you right up against the side of the wall." I liked to challenge the audience. (235)

[On Hank Williams:] I wanted to be like him. We all did. Even his contemporaries held Hank in awe. Faron Young brought Billie Jean, Hank's last wife, to town for the first time. She was young and beautiful, and Hank liked her immediately. He took a loaded gun and pointed it to Faron's temple, cocked it, and said, "Boy, I love that woman. Now you can either give her to me or I'm going to kill you."

Faron sat there and thought it over for a minute. "Wouldn't that be great? To be killed by Hank Williams!"

He wound up driving Hank and Billie Jean around in Hank's Cadillac, with the two of them loving it up in the back seat. All of a sudden, it got very quiet in the car. Faron thought he should say something. "Hey, Hank, that left fender got a little rattle in it."

"Shut up, boy," said Hank. "Watch the road and keep driving. I bet you wish you had one that rattled like that." (237)

Both Hank's ex-wives said I reminded them of Hank. Billie Jean, who later married Johnny Horton, came to town one time and wanted to meet me, so Harlan brought her over to the office. Johnny had been killed in an auto accident. She asked me, "What are you doing later when you get off?"

"Look, lady," I said, ''you killed Hank Williams and you killed Johnny Horton and you stunted Faron Young's growth. So you just leave me alone." (238)

I liked Jerry [Bradley], but he drove me a little nuts. He didn't have a clue about music, though he always tried to get involved in it, usually by remote control. l'd bring him a finished song, and he'd say, you need to do this, you're going to have to chang so-and-so, and I'd go back into the studio and pretend to move the faders, and he'd okay it. He never knew I didn't fix a thing. (242)

He was a good merchandiser, though, and Wanted: The Outlaws was his baby. A reporter from The Tennessean had once asked him if he would support this so-called "music of the future," and Jerry said that if I was selling the amount of records that Charlie Pride did, he'd be a fool not to. Sure enough, Neil did an audit and found I was already selling more records than Charlie. After that, he jumped in front of the bandwagon and started pulling.

I didn't like calling us the Outlaws, because there was already a rock band named that; my idea was "Outlaw Music." If I had to do it over, I'd argue till I almost got him convinced and his mind changed, and then I'd quit. In hindsight, it did work out pretty well. (243)

It was touch-and-go for about three or four days. They had found a couple of plastic bags in a trash can to the left of the toilet, which had a cocaine "presence." I was clean. Still, the next morning they took me downtown to be fingerprinted at the federal marshal's office. "Damn, I hate this," said the marshal as he was rolling my fingers through the ink.

I said, "Shit, well don't do it." (264)

I found out right there that if you're ever in a situation where they try to scare you, you're dead if you show fear. But if you don't fade under their pressure, you scare them. It helps to be a good card player. I saw that. They got nervous, and I was never nervous. There's only two things they can do, I thought: put me in jail or leave me alone. (266)

Willie [will] be the first to admit that he actually enjoys getting me in trouble. "It keeps Waylon alert," he likes to say. "He could sit over there and get old and weak. I keep him young by sending him problems."

If that was the case, I'd be a babe in arms now. I write a lot of songs about Willie, because I have never thoroughly understood him. He's like a cartoon to me. I'll be the first to his door when he's in trouble, but he could screw up a two-car funeral. He's so smart, but he never learns a thing from anything that happens to him. (272)

There was no chance that The Dukes of Hazzard television show would prove too smart for its target viewers. (281)

They liked the way I sounded, so they asked me to write a theme: "Just two good ol' boys / Never meanin' no harm .... Been in trouble with the law / Since the day they were born." They thought that was good but said all it needed was something about two modern-day Robin Hoods, fighting the system. So I wrote "Fighting the system, like two modern-day Robin Hoods," and they didn't even know they wrote the damn line. It was my first million-selling single, and one of the easiest records I ever cut. (282)

These Waylors could have stood on their own. In fact, whenever I disappeared from a session, Richie cut most of an album on them. But when one of the members came to me and wondered when he was going to get equal billing, I had to draw the line. "Sorry, son," I shrugged. "I'm gonna tell you something you might not realize.

"I'm all you got." I put my arm around his shoulders. "Tomorrow, if you leave, they're going to say, 'Where'd he go?' And I'm gonna say, 'Well, he ain't here no more,' and they'll say, 'Damn, we're going to miss him.' But they're still going to be out there, waiting for me to come around and count down the set. It don't work the other way. That may sound awful and conceited, and maybe it ain't fair, but it's true." (284)

The Hell's Angels had the run of the place. I broke a tooth before I went on and did my whole show with it cracked straight up. I almost reached in there and pulled that sonofabitch out. Willie said, "If you decide to do it, be sure and tell the audience." I have never understood what that meant. (285)

Marylou wasn't used to the open cocaine use up in the office, and the stash-sharing cliques that went along with it. For a time she felt like an outsider. Then one day she put a tiny bit of Coffeemate on her nose and walked around. She said they treated her differently from then on. (295)

I leased a house in Arizona with the help of my friend Bob Sikora, who was still running clubs like Mr. Lucky's in Phoenix and owned a string of Bobby McGee's restaurants. It was out in the desert, and I've always respected the spiritual purity of that stark land. Jessi's dad had lived about eighty miles as the crow flies southeast from Phoenix, down below Superior, around Rey [sic; Ray] copper mine. It was wilderness. He built a cabin along the Gila River, and in the morning you could get up and see prints in the sand, where mountain lions, rattlesnakes, and wild boar had been.

I'd go out there to taper off drugs, and it seemed to help. The desert would soothe me; I could exist without stimulants for weeks at a time, drawing on the desert's silent company. Jessi's dad built race cars in the twenties, and he had constructed auxiliary motors that ran the electricity and water, along with other gadgets. He'd tinker with them, mining his claims for molybdenum and copper, sure he was going to make a fortune. We knew he already had. In his own way, he was a genius. He had found a piece of the world that he belonged in.

You had better respect the desert, because the desert leaves it up to you. It's not going to help. There's nobody you can pay to find your answer and bring it to you. You can't set back and wait on it. The desert is going to leave you totally alone, to see if you can find the strength within yourself to survive. There are no distractions. You can't outfox the desert. You'll die trying.

The house was on the desert's edge, in Paradise Valley up by Tatum Boulevard. (303-4)

"Cash," I said. I didn't mean Johnny.

They had asked me how I was going to pay for the gold Cadillac. It had a wheel in the running board and was long nosed, stretched like a limousine. I had been looking for a Fleetwood. This was a Seville, one of only five made. I couldn't resist. I had told the dealer in Scottsdale, Arizona, that I was going to come back for the car, and here, on this Saturday morning, there was a crowd of people waiting to see the transaction.

Jessi stood next to me. I reached in the top of her brassiere and pulled out a few hundreds. Then I pulled out a few more. I kept reaching and pulling until I paid the whole forty-five thousand dollars. Every now and then I'd pinch her and she'd squeal. The guy was so flustered, he had to keep writing up the order again and again. (315-16)

The nurses chatted among themselves while they took my vital signs. They were talking about a gang shooting that had happened the night before. They'd brought the guy into the operating room and were working on him, and the rival gang came in and shot him some more on the surgical table. I felt like I was in good hands. (320)

Autobiography. It's like a travelogue. You think, "I've been somewhere," and you want to tell people about it. Maybe they'll see some of themselves along the journey, but most of all, you tell your story to get it straight, at least in your own mind. To figure out what you've done right, and where you've one astray, and why maybe the wrong things turned out to be needed for the right things to happen. (325)

I got Haley back when she had chicken pox. She hated having those spots on her face, and finally I told her to gather a few of those pox when they fell off and put them into an envelope and send them to President Carter 'cause he'd just raised my taxes. She turned to her mother. "Way-a-lon is i sometimes so silly." (327)

[On his son, Shooter Jennings:] He's got more than one vote in our family. It may jump up bite me in the rear end one day, but I've always told him, if I say no to you, you have a right to ask why. If I don't have a good enough answer, then I'll try to see it his way. The best thing I can give him is my ears and my attention. A lot of times, especially with my other kids, I haven't followed through. I blew it in so many ways with them, back when I wasn't much more than a kid myself. (328)

The album was beautiful, he kept assuring me, only he wanted us to keep cutting sides. Change a verse and a chorus. Remix and remaster. I said, that's bordering on fucking with me. By the time Too Dumb came out, in 1992, we were both pissed off. Epic sat on the record, big-time. (333)

I didn't mind a bunch of new mavericks on the scene. But Epic was telling me my time was over with. People don't want to hear you sing. Radio don't want to play you no more. One day I went up to their office. They asked me to call up radio stations and influence them to play my record. . . .

I thought, boy, there was a time when I wouldn't do this. Then I thought again. What did I mean, there was a time? I ain't doing it now. I told Marylou, "Let's get in the car." (334)

I'm proud to say that I'm a personal friend of Big Bird. Whenever I appear in the New England area, Carroll Spinney and his wife. Debbie come visit the show. . . .

He is transformed when he puts on the yellow Big Bird costume, all eight feet tall, his hand up in the air making the movements of the mouth and eyes, and the other moving around as the Bird's wing. There's a television set monitor inside the chest, so Carroll can see what's happening outside, though he has to do everything backward. He's the only Big Bird that's ever been. (335)

Inside the vocal booth, Ocean Way Studios, Hollywood:

"You look like the guy who picked up the check for the Last Supper."

"One more mistake, and out you go."

"Willie tuned me out so long ago, he can't hear what I'm saying. Look, he's pretending to listen to us."

"Everybody turned everybody off."

"Want to do that one all over again?"

"I'll do it all over you."

"I don't give a shit. When you figure out I really don't give a shit, the world will be better for you."

"Could you move it over a little bit, so I don't have to stare at your ass?"

"We're gonna make a hillbilly out of you yet."

"Kris, tell them to kiss my ass."

"It may look like I wasn't paying attention but I am."

"You gotta put your headphones on, or should I kick you when you're supposed to come in?"

"Aren't you glad you're you?" (361)

When we first took the Highwaymen out live, it looked like four shy rednecks trying to be nice to each other. It almost ruined it. That didn't work, for us and the audience, and it was really bothering me, how different we were on stage than when we were sitting around in the dressing room. We had just come back from Australia, and were set to play a week at the Mirage in Las Vegas. After the opening night, I was fixin' to quit. I talked to John about it and he was feeling the same way. "I get a little nervous," he said. "I don't want to look like I'm trying to steal your thunder."

That was it. We were boring each other and the audience. It may be hard to think of Johnny Cash as intimidated, but that's the way we were. You can't have four big guys tiptoeing around each other on stage. Nobody has a good time.

So we decided to help each other out, whether each of us thought we needed it or not. Don't ask. Just do it, and don't worry what the other one thinks. Make fun of each other, cut up, poke some much-needed fun. (363)

There used to be another group called the Highwaymen, who were best known for the folk tune "Michael Row the Boat Ashore," and they sued us over the name. They had long since retired, but we did a charity show with them opening and squared it away. (364-5)

Kris [Kristofferson] taught us how to write great poetry. Politically, he swings us to the left; and I'd hate to think what would happen to him if Leonard Peltier was guilty. He wants everybody to have a fair shot, even if they're wrong. (369)

It's tough to get us singing in harmony. Kris and I are probably the closest in voice; I can phrase with Willie better, since I've been doing it for so long. I know where he's going, even if I can't figure out why. (370)

Thinking about who might help us out, I remembered someone who had worked with all of us at one time or another, that "good friend of mine," Jack Clement.

It seemed like a reasonable idea to bring Jack along to watch over the board. After the first night, however, he called Willie in the morning. "Come on down to my room, Will," he said with that lilting melody in his voice. "You've got to do something about your rhythm. You start in last week and wind up next week. You're not on the beat. You've got to sing on the beat."

"Fuck you, Jack," retorted Willie, and then came back to me chuckling, and said, "I've always wanted to say fuck you to somebody whose real name is Jack." (370)

I said, "Jack. I want you to listen to me. The soundman you're working with can't speak English. He needs you, and we don't. Consider the front of the stage out as your domain and leave the rest to us. And especially, stay away from Willie. I'm one of the few people who can tease him about his singing. As far as rhythm, that's his style, the back-phrasing and everything. He spent years figuring out how to do that."

It went along pretty well until Jack tried out the local schnapps. He got in the elevator with Willie and a bunch of other people and said, "You're really fucking 'Good Hearted Woman' up. You're doing it twice as fast as you're supposed to."

It's tough to light Willie's fuse, but he was on the phone with me in seconds. "He's driving me crazy," he yelled. . . . Willie wouldn't slow down. "I want him out of here." Then he stopped short. "Do I do 'Good Hearted Woman' too fast?"

I said yeah, but Jack wasn't the one to tell him.

It was my job to break the news. I took John with me. "Willie don't want you here," I said. "I told you not to bother him."

"I didn't mean no harm," said Jack, a little sheepish and hung over. And he didn't.

Kris came by a few minutes later and John told him what had happened. "Oh, no," said Kris. He was on his way to smoke a joint with Willie before we went on.

"Wait a minute," I said. "Why don't you smoke two joints? When you get about halfway down on that second one, lean over and say, 'Maybe you were a little hasty about Jack?'"

Sure enough, Willie comes back, eyes twinkling, and half-smiling. "Aw," he said. "Let's give Jack another chance. I'm sure he meant well."

That night, Jack was behind the mixing desk, choreographing the show in his mind, slapping the echo and twiddling the eq. Doing his dance. (371)

We were up in Galilee, at Peter's house, and came back through Jericho. As we started the return to Jerusalem, the four of us crammed into a van, I looked out over the desert. There was the brightest little pin of light I'd ever seen. I asked the Palestinian who was driving us what it was, and he said he didn't know.

As we got nearer, it grew brighter. I began looking for three camels on the horizon, bearing gifts. Finally, I saw that it shone from a Bedouin tent, stark against the wilderness. They're nomads, and they've been moving back and forth the beginning of time. It was quiet, and the night had turned cold and clear. At first I thought the light might be a campfire. Then I took a closer look, and saw it was the glow of a television. (380)

When people me who I most admire in the world, I always have the same answer: Muhammed Ali. . . . After Shooter was born, I called him and told him we were having a christening. ''We'd love to have you," and sure enough, he showed up and flopped down on the couch. "I'm here to integrate this joint," he said with a smile. Then he cast his eye over to Deakon. "And I'm lookin' for a heavyweight to fight tonight." It was the only time I've ever seen Deakon say "not me."

I had just bought the bus we called Shooter 1. It wasn't even furnished yet; I don't know if it had license tags. Muhammad asked me for the keys, drove to Louisville to see his momma, and then brought it back. He could have kept it for all I cared. He means that much to me, and the world. (384, 385)

I do know that my new direction is for the better. I have a stable, easy life; everybody around me tries to take care of me. I may have to watch what I eat, but Maureen cooks meals that are as healthy as they taste good, Jessi pumps vitamins down me and makes sure I take my medicine, and Shooter tells me what White Zombie is up to on the Internet. (394)

|