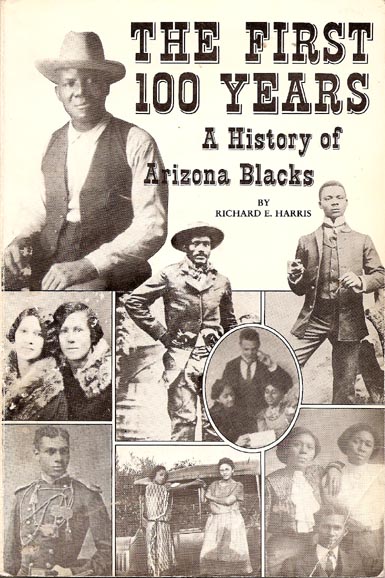

The First 100 Years: A History of Arizona Blacks

Richard E. Harris (1983)

Mary Green . . . was the first Negro resident in Phoenix. (3, caption)

Concerning interracial marriages, which were declared illegal by the new Statehood Constitution of 1912, a researcher offered an apparent illustration of how the matter had been dealt with. "There are people in Tucson of Negro descent but who identify themselves as white," he said. In a sampling of 20 Negroes, he claimed that only three had married within their race. Among the others, three married Indians, five wed Mexicans, one an Anglo and the other, a French woman. The rest of the 20 had not married, but all were property owners, he added. The findings seemed an indication of the new-found advantages and freedoms of Blacks in their western homes. (7)

His name was Jeff. Period. A cowboy in the most romantic sense, riding herd, breaking wild mustangs, gun-battling with rustlers or sheepherders, or carousing with the "boys". He came to the Holbrook-St. John area with the Greer family in 1877. The powerful clan from Texas soon came in conflict with neighboring Mexican sheepherders over territorial and grazing rights. First, it would be the sheep herds shot at and scattered. Then the Mexicans would retaliate and stampede the Greer cattle.

Eventually girding for more trouble, the Greers brought in both Anglo and Black cowboys for reinforcement. The sheepherders, in response, drafted gun-slingers from New Mexico. These moves prompted caution on both sides, and an uneasy peace prevailed by 1883, as the Mexicans controlled the town of St. John's, the Apache County seat. The Greers, meantime, enjoyed the friendship and influence of the Territorial government and the judiciary. In an obvious ruse, the Mexicans invited the Greers to a fiesta, promising a bargain basement cattle sale. Instead of seeing the traditional bull fights and fire-cracker display the shocked guests found themselves ambushed by blazing gunfire. Only Jeff and two other cowboys managed to escape after Jeff was wounded while covering for his buddies. Two Mexicans were killed and the Greers were jailed on murder charges at Holbrook. Sixteen Mexican deputies tried to get permission from the judge to take Jeff and his companions back to St. Johns to stand trial. Certain for sure that the three would never reach St. Johns alive, the jurist refused their request. The cowboys were ultimately freed.

Some accounts say that Jeff, after 20 years of ranch life, its hard ships and excitement, went to Los Angeles to work as a taxi driver. (22-3)

Nat Love, the ex-slave who left Tennessee because "smart Negroes were not much in demand" went on to ride through the ribald, rugged new West to prove that he was an excellent Black cowboy as well as a proud American. His deeds, his escapades, sometimes hilarious, sometimes blood-curdling, his broad itinerary, his love affairs, however, were not to be overlooked or hidden away. He penned his own "The Autobiography of Nat Love, Alias Deadwood Dick" in 1907 for all the curious to peruse. (28)

By the 1890's when the frontiers were virtually settled, Nat at the age of 36, decided to settle down. As a Pullman porter, he traveled on an "Iron Horse", eventually marrying in Los Angeles. In putting on paper his life story, "Deadwood Dick" evidently spiced it with a bit of horse drippings. But what autobiographer hasn't? (30)

Bouse Wash, located on U.S. Highway 60 between Hope and Brenda, was to be something of an Utopia for some 500 "Pilgrims" from Los Angeles in 1925 before realizing they had been hoodwinked by a city slicker. Mrs. Rosie Riley, along with her late husband said they first learned of the lands while attending church services. "Two white fellows came to our services in Los Angeles, and told our people they had located some good homesteading land," she explained. "They said they would survey it, lay out the section lines—all this for a dollar an acre. They also promised to dig wells until an irrigation canal was built."

Nothing ever happened, except that the swindlers skipped with the money gotten from the approximately 300 acres that most of the families purchased. The lands they brought were located in a low section which always flooded during heavy rains. Somebody named the section "Nigger Flats" which stuck for a long time. Most of the families gradually pulled stakes and returned to California or Phoenix, as did Mrs. Riley. Clarence Thomas was one of the few to remain. In the late '70's, while employed nearby as a porter, he reflected on his sad experience. "I came here to be a farmer, but they wouldn't even write insurance on us. We couldn't even borrow money enough to bring us water or buy equipment. People came here with a dream of having their own land and being their own boss. It was terrible for us." (40)

Around this same period of time, another group of Negroes from southern states purchased a sizeable plot of land 40 miles south of Phoenix, between Gila Bend and the little town of Maricopa. They named it Mobile, after the Alabama city from which some had migrated. Lack of adequate water, naturally, was the biggest problem for the 58 families; their only source was from the property of the little adobe school. (40-1)

A special fleet of trains pulled out from McNary, Louisiana, in 1924, transporting approximately 700 lumbermill hands and their families to a town in Northern Arizona which the company executives would call McNary, just as a newborn baby may be named after its dying father. Those folk were beholden to the Cady Lumber Company whose lands were virtually denuded of trees after years of being over-worked. It was said that the company owner, A. Cady, had too much respect and faith in his Black employees to leave them suffering in the barren southern site. It cost a small fortune to corral the special locomotives pulling passenger and box-cars and flatbeds to the northward hegira. The families brought all their possessions, including fowl, pigs, cattle and pets. (43)

When the area around the little town of Randolph, 60 miles southwest of Phoenix, began blossoming out as an agricultural oasis in the late '20's, farmers were hurting for field hands. But thanks to the farm labor contractors who were paid $25 for each live body delivered, farmers were getting the needed labor. At first the migrants had to make their homes in crowded accommodations provided during the August-through-March harvest seasons. Eventually though most of the workers and their families managed to rake up enough money to build their own homes of slightly better grade. (44-5)

"Once we couldn't never get any water worthwhile. We had to pay $2 a barrel for it to be hauled to our homes," he continued. "But folks got tired of that and started leaving Randolph. Ain't much of a town no more, except old folks and children. Soon as the children grow up, they go, too." (45)

Records show that a Moses Green, in 1870, was the first Arizona-born Negro. (47)

As it was put by a 92-year old who came to Arizona in 1916 after stays in Georgia and Oklahoma: "At least they didn't lynch you here, like they did back there." Harassment and rank discrimination, yes, but no record of lynching of Blacks in Arizona are found. (51)

Ms. Irene Rosser, a daughter of early Phoenix residents Richard Rosser, recalled in 1976 of seeing hooded Klansmen march into the First Colored Baptist Church, dropping coins in the collection plate, then silently marching out. As a young lady then her thoughts were, "They were just telling us to stay in our places." (52-3)

For Negroes in Tucson, the state's second largest city, the story surrounding education and schools, was somewhat different. A few "influential coloreds" had requested a segregated school, though elementary classes had always been integrated. In early 1912, school trustees caught in the middle of controversy between Negroes who wanted segregation, and those who did not, acceded to the former faction. (63)

Johnnie Credille, the first graduate of the Phoenix Union Colored High in 1918, later finished Howard University. William Clay, 1919, became an orchestra in Los Angeles. [Sic] (66)

Phoenix Union Colored High [was] later renamed Carver High School. (67)

The town of Scottsdale, adjacent to northeast Phoenix, and which termed itself "The West's Most Western Town", was completely out-of-bounds for permanent Negro residency. However, it made one exception in 1959 when the Boston Red Sox baseball team, under pressure from the Massachuesetts [sic] Anti-Discrimination commission for not hiring Negro players, got concessions to house its first non-white players, Pumpsie Green and Earl Wilson, in the second rate "Hitching Post" motel. All white players were roomed at the first-class Safari Hotel. In contrast to this action was the stand taken by Leo Druoucher [sic; Durocher], manager of the New York Giants, one of several major league teams holding spring training in Arizona. The flamboyant Duroucher [sic; Durocher], according to informed sources, demanded that his Negro players be accepted at the prestigious Phoenix Adams Hotel along with his 50-member squad. So, Willie Mays was among the first Negroes to room at the Adams. (96)

NBC and independent KPHO also had Black reporters, and KPHO also inaugurated the long-running "Get It On" weekly Black talk show. (110)

While accounting for only a small percentage of the electorate in any Arizona municipality or county, Blacks have elected members of their race to councilmanic seats. (119)

[JOHN BARBER (came to Phoenix in 1918):] When I came here, the Mormons mostly ran things, and they had funny ideas about us. Didn't think we had any soul or could go to Heaven. They've changed now, I hear. (125)

[WESLEY LARRIMORE (came to Phoenix in 1920:] All the barber shops except one, was owned by Colored, who cut everybody's hair. The Adams Hotel building always had a Negro barber. The women had beauty shops—Mrs. Walker was one. Negroes also had a few cafes and restaurants. Interesting how Caucasians would let us use razors and scissors on them, then wouldn't trust us in their places. (129)

[LARRIMORE:] Do I think genealogy is important for young folks? Youngsters got too much of nothing on their minds. No, I don't think so, unless they're educated. Ask the young ones about it, and they don't know what you're talking about. (130)

[H. B. JACKSON (came to Arizona in 1923:] When the timber began to run out in McNary [Lousiana], the town's name, the company made plans to move their entire operation to Cooley, Arizona. They renamed it McNary, and most of the colored workers and their families started moving to Arizona in 1922-23. They were brought, along with their pets, live stock and furniture, in flat-beds, box-cars and passenger coaches. Our family left in 1923 on the trip that took four days. The workers paid part of their fares, and the company, the other part. (131)

[DR. LOWELL C. WORMLEY (came to Arizona in 1942):] My next position was as chief of surgery at the Poston Hospital, near Parker, serving the Japanese who were in the internment camp there. I had always liked Arizona, so after six months at Poston, I decided to set up practice in the state. (139)

A hardy lady of pioneering spirit and keen foresight, Margaret J. Campbell apparently nurtured a prophetic vision of the Twenty-first Century. More than 40 years before the current vogue towards underground homes, she made it an accomplished reality in Tucson.

For Mrs. Campbell the two-level home she dug with her own hands, was a chance to be rid of the dust, wind, noises, insects and arthritic pains that bothered so many Arizonans. This remarkable lady did not merely sit around staring at the earthen walls when her project was completed. She found time to study and learn German, French, Spanish, Arabian and Hebrew. She also taught piano lessons to youngsters.

Perhaps, most remarkable, Mrs. Campbell who died at the age of 71, wrote and published a novel Iba, The Dawn, a thoroughly fascinating tale of adventure and romance. She relates an exciting saga of men who rebuilt the world after the Great Flood.

The story pictures Africa as the Cradle of Civilization, where Noah walked and conversed with God. One of the characters, says significiently, "Seek to discern Beauty in all things that God has created. For it pleaseth them to have varities in forms, varities in color; even in the skin of men."

Born in North Carolina, one of 10 children, she was raised in Cincinnati. Her love for reading and writing came quite naturally, for her father had published books of poetry and essays, she said. For health reasons, she came to Tucson in 1942, and started her underground domicile a few years later, in the rear of her residence at 1926 South Santa Rita Ave.

"You know," she once said, "my neighbors thought I was a little cracked when I started this digging. Now, they're not so sure. Lately some have started about doing the same thing."

Mrs. Campbell had another reason, other than health, for going underground. "For many years I dreamed the earth was to be overcome by polar icebergs," she revealed, "In my dream I see the sun disappear and the earth start cooling, covered with ice. I really believe this may happen in the next 200 years." (141-3)

|