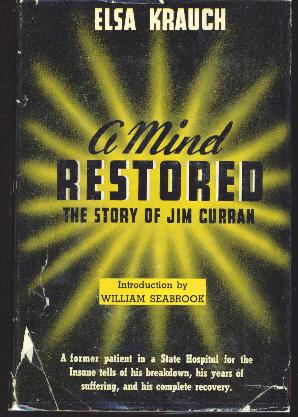

A Mind Restored: The Story of Jim Curran

Elsa Krauch (1937)

[From the Introduction by William Seabrook:] When my own family learned I was headed for Bloomingdale, my now sainted aunt who probably still wears bombazine in heaven, but was then living in Hawkinsville, Georgia, wrote:

"—but think of the shame! I'd rather see Willie in a drunkard's grave than shut up in a madhouse."

If my pious elderly female relatives had had their way, Willie would now be in a drunkard's grave—and that, with all its implications, is why I hope to God a great many people will read this book. (xi-xii)

The first thing I remember is that I was in a high chair with my left hand tied behind me, because I was so definitely a left-handed baby. (4)

I remember the teacher in the sixth grade who made me write with my right hand. She would come up back of me, softly, when I was using my left hand, and rap my knuckles sharply with the brass side of the ruler. I was very nervous about it, and failed in one of my eighth grade examinations because I could not write fast enough with my right hand to finish it, and had to go back to the grade school for history every day while I was a high-school freshman. It was very humiliating. (7)

I remember that it was raining and hailing, and that we were on the way to the cemetery. My mother was dead. Never again would I find her waiting for me in the living-room when I rushed back from school in the afternoon to talk over every detail of the day with her. . . .

I had loved her very, very much, and I was sure she must have known it. Then, suddenly, my Aunt Olive touched my arm, and turned her tense, handsome face with the dark eyes on me. "You know, Jim," she said, "you were always a great worry to your mother, and made her very unhappy." Just that. She said it without kindness or sympathy in her voice. Then she turned away from me again. My blood froze. My grief was already deep. But this! I had never suspected this! What had I done? And when? (8)

I remember failing in my physics examination in my senior year in high school. Once more that slowness in writing. I had to go back to high school for an extra year. It was crushing. My friends had all gone on to the University. Some one referred to me as "the cow's tail, always last." (10)

One of my partners, who was a much older man than I, often said to me: "Jim, I don't know what I'd do without you; I am such a plunger, and you are the balance wheel; you always seem to know how to advise me sanely." Think of that, and then try to realize how little any of us can guess what life may bring us.

I believe that my most grievous worry at that time was that I was getting bald. My hair, which was formerly very thick, was coming out in handfuls—literally, handfuls.

What an ironic circumstance! Friends used to say to me with a kind of comforting laugh: "Well, at any, rate, you know you'll never find a bald-headed man in an insane asylum." You see, one never knows. I worried about the loss of my hair, which was, after all, not so serious an affair; but neither I nor any one else thought that I would ever lose my mind. (16)

I wasn't brooding or worrying, and being alone didn't depress me. But it was a bad habit to get into. And life was soon to hit me an awful wallop. (18)

There was that purchase of a large piece of land on an island. What for? Not for investment. Not for a happy home. No, not that. I thought, here is a place where I can go to be by myself. I shall have it planted in fruit trees, and after a while I shall come here to live. Fishing and hunting are to be part of my program. I shall stay here for always. (20)

We were making money fast, and it wouldn't take long to save enough to satisfy the urge that was now upon me—the urge to become a recluse, to creep away. I had already retreated from life mentally, and I was preparing to do so physically too, as soon as possible. I was planning a renunciation, a hermit's existence. (20)

Gradually my mind grew more and more tired. I cannot express it in any other way. My mind grew tired, and I found it hard to think or plan, or concentrate on any one activity for any length of time.

The worst of it was, no one understood it. I did not understand it myself. I wanted to keep other people from knowing how hard it was for me to work. It was as though I had attempted to hide from others the fact that my arm was broken, and then had gone on trying to work with it while it was in this condition. The arm would certainly have kept getting worse, wouldn't it?

Well, my mind did the same thing. It kept getting worse all the time, while I was urging it to do work too hard for it.

I could see that our business was going downhill, but I could not do anything to stop it. No, I could I not. Nor could I make any definite decision to get out of it. Hesitancy and procrastination are all part of depressive mental illness. I saw the end coming, but was numb with fear. Our business went down with a crash that was terrific. (26-7)

When Caroline was gone I at least did not have to face the ordeal of seeing her concerned, and of hearing the children say: "Daddy's so cross."

Cross, when I loved them so! But that is what is most heartbreaking. The very people who are closest to you, the very people you like best—these are the ones to whom you become irritable when your mind becomes disordered. (32)

Because, you see, I had the same idea about mental trouble that most people have. I thought that to be a mental case was to not know who or what I was; that I would perhaps imagine I was some famous personage; that I would howl and rave. None of these things happened. I knew who and where I was, always. I was very quiet; I did not scream or say irrational things.

My doctor had no suspicions either. We were great personal friends, and he was worried about me, but thought that my financial troubles had made me lose my grit, and become lazy—while the truth of the matter was, that I had never worked so hard in all my life! But no one could guess this. My labored mental efforts never aroused me to effective action. I merely sat and watched with a kind of helpless horror as my life collapsed around me. (33)

Fear, when it once attacks you, does not require any good reason for being. It is there—that is all. (39)

My relatives had a new idea. They said "a change of scene." Of course. Relatives often say that. And what a great mistake it is. A disordered, confused mind—add to it the necessity of adjustment to a new environment, and what have you? A fatal state of affairs, that's what. (40)

Perhaps I would "snap out of it." That phrase! I've grown to hate it. As though any depressive ever could "snap out of it." (40)

On a summer evening I stood on a high bridge, and looked down into the water below with strange excitement. One jump, and all this agony of trying to make decisions, of working out ways to build up a slipping business, would be over.

Easy to think about—but not so easy to do! Not easy at all! Suppose the attempt should be a failure! Suppose I should not drown. After all, I could swim a little. How ridiculous I should appear. Everyone would know that I was "queer." No, I must be sure.

At another time I held a gun in my hand. A friend of mine came into the room unexpectedly, and I put the gun away quickly. My friend, sensing my tense mood, insisted on taking me home with him for the night. By morning the world looked brighter, and I was ashamed of my cowardice. (45)

I never saw a chart during my entire stay. There was no routine, and, as I discovered later, there is nothing so helpful to a mental patient as routine. (47)

The Catholic Church in Haywood was not far from the Sanitarium. I walked down on Sunday morning between the rows of trees on the quiet streets. But I could never sit through the mass to the end; that old restlessness was still upon me. One day Father Rupert came to speak to me, and I told him who I was, and apologized for not being able to remain quietly in church as I should.

He considered a minute before he suggested: "Sit in this pew near the side door. Then, if you feel that you cannot sit still any longer, just slip out quietly."

You know—this plan worked! When I found I didn't have to stay, I didn't get panicky—at least not often. (51)

Even in my agony I recognized that there was something ironically humorous in the prospect of saying: "Paddy, my friend, will you please drive me to the madhouse tomorrow?" (66)

This matter of suffering. Do not think for a moment that mental patients do not suffer.

"Of course they do not really know what is the matter with them." "Of course they do not suffer." These are the things—the ridiculous things—that people say.

Suffer? And what is the verdict of people who have undergone the most excruciating physical pain, and then been mentally ill? The doctors can tell you. These people say: "Rather all the physical illnesses—every one of them—over again, than mental breakdown." Or, more simply, "That's the real hell." Torture.

There is never any getting away from it. Your body seems shaken by it. It gives you no rest. It is like a mental flagellation—always, day and night.

The minute you wake up it is there. All day long it is there. Whatever you try to do, it stands in your way.

And sometimes it is like a big, threatening obstacle. But you have to put up with it. You think: "Isn't there something the doctor can cut away?" (95)

Perhaps the best way to explain it is to say that it is like an unpleasant noise; but a much more unpleasant and awful noise than anyone who is sane could ever imagine.

Think of a noise like that, the worst, most grating, most nerve-racking noise you ever heard; then imagine that it never stops, never, never for an instant. Imagine that you recognize this; that you know the noise will never stop. That it will go on in this way forever, tearing at your nerves, pulling at your muscles, goading at your mind, deriding you, reproaching you, sneering at you. Then maybe you will not blame us for thinking of suicide. Then maybe you will no longer say, "They do not suffer." Yes, we suffer. (96)

There is something lonely about the sound of a train rushing along in the dark, and these trains were always whistling—a long, mournful whistle—as they neared the Hospital grounds. (98)

And when it got to be three o'clock! You who have never been mentally ill can never know the horrors of those awful hours between three and six in the morning. Only a depressive knows what they can be. I would wake up, and wonder where I was. Then I would remember. I would remember everything in one awful wave. A wave that washed over me, and drowned me in misery. (111)

So they said I was lazy, did they? That was the complaint that had been made against me. Lazy, yes. Lazy as a sick man is lazy. Lazy as you are when you break your leg and cannot walk as a consequence. Lazy as when you have a fever and cannot think. That was the way I was lazy.

But no one would believe that. No one but the doctors here. And Dr. Harris, of course. Not even Dr. Smith had realized for a long time. People can see when your arm is paralyzed, and they are sorry for you; but they cannot see when your mind is held stiff and immovable. That does not show on the surface. (113)

When they were ill they went to a hospital, and stayed until they were strong again, and then came back. No one blamed them, no one despised them for it, no one looked at them strangely when they came back. Everyone helped, was sorry, protected them until they were strong again. If they would only do that for me! (115)

I winced, and I pulled out a cigarette—if I had one. And right here, I want to say: "Tobacco, I salute you."

Honestly, no one outside can ever know how much tobacco means to men in a place like St. Charles. If we had no money we were given a corncob pipe and a small supply of tobacco, free—pretty bad tobacco, too. Of course we were glad to get any at all, for men are men everywhere, and when there is little to do, time on one's hands, and trouble to bear, tobacco is almost more welcome than food. (118)

Much we could see with our own eyes, and more we heard through the grapevine route that exists in every Hospital. One man came in praying loudly, but bound at wrists and ankles, for he was convinced that it was his duty to kill everyone in sight, in order to punish mankind for its sins. He thought that God had sent him as a special messenger; and he had made several homicidal assaults. He was soon removed to one of the "bad" wards, and we did not see him anymore. (121)

One helper, a patient, lathered the men, swearing terribly as he did so. This had nothing to do with his feelings toward us, as I discovered. It was just his way. His language was ferocious and obscene, but no one paid any attention to him, after we got used to him. He loved the importance of his lathering job, and scarcely knew what words fell out of his mouth. His mutterings were invectives directed against some woman. (128)

Pete was also very efficient about his duties, but he had warped ideas about some other matters.

Two things particularly bothered Pete; he loved crosses, and he hated red. He laid everything out in the form of a cross when he was sorting things. Everything. A pair of socks or a couple of shirts or pieces of string. Strips of dark paper in the form of crosses were pinned to the window curtains of his clothes room. He did not know why he did it. He only knew he must. That was his obsession. It was harmless enough, and no one tried to stop him.

Then there was red. Red was something Pete could not bear. It did things to him. Come in wearing a red tie, and the curled ends of Pete's mustache seemed to crimp up even more tightly, and the dark eyes over his beak nose flashed fire. (131)

As to our mental condition—most of the time we were at the mercy, so to speak, of our attendants, and they could help or harm us, according to their desire or disposition. Every little remark is important when you are brooding away in mental darkness; if, for example, a doctor or attendant says "if you get well" instead of "when you get well," that can keep your mind churning about in despair for years. (137)

Occasionally the comments made by the Board were rather absurd. One patient who was homicidal, and who had tried to kill his wife, was brought up one day, and one of the women on the Board asked reproachfully: "Now, do you think that was a nice thing to do?"

Even we who heard it, we who were mental patients and as such were not supposed to understand very much of what was going on, were amused by that. (144)

In the Hospital they gave us a place to rest; they gave us every help to build us up physically; they planned our lives for us so that we would not be forced to make plans for ourselves while our minds were befuddled; and they relieved us of the necessity for adjusting ourselves in a world that could not understand us while our illness was upon us.

And they tried to explain and encourage. What more could they do? (152-3)

Our beds were comfortable; we slept on hair mattresses, and they were always in good condition. On one of my walks I came upon the mattress renovating shop. The hair was washed at the Hospital laundry and brought to the little shop where it was stuffed into the new mattresses. (154-5)

I used to wonder at some of the articles the men in this building made to sell. They were displayed in cases in the lobby of the Main Building. Strange to think that these men, many of them desperate characters, were working on bright plaques, crocheted or knitted shawls, dainty bead necklaces. They paid for the materials out of their own funds, and the money from the sales was credited to them. (156)

"And that," he finished, "might happen to anyone. Everyone has a breaking-point. And no one knows what his own particular breaking-point is until the test of life has been applied to it." (174)

Queer sights. One day I noticed a woman who must have thought she was a fashion model. She was very stout, and her hair was straggling down her back. Her underskirt hung in uneven lengths below her dress, and she wore dark cotton anklets and scuffed shoes. But she held her hands on her hips, and her head up high in the way that professional models do. She walked up and down the strip of center carpet in the corridor of her ward. With mincing steps. I suppose that she imagined that she was wearing fine silks and laces, and was showing them off to the other women. (177)

There was one man who was in "Detention" for a little while. He was a farmer who had lost a great deal of money, and his, mental stability with it. They brought him to the Hospital, and he was kept in "Detention." He wandered about the ward continually, calling "Oo-oo-oo-oo-mamma-mamma, mamma, mamma." "Mamma " was his wife, and he missed her, that was sure. But it was hard on us to hear him keep up that call continuously. And he did keep it up. All day long. Maybe at night too, although possibly they quieted him somehow. I slept upstairs at that time, and do not know. (180)

Then there was the man who would not talk. Not to anyone. He was an iron worker, a man of medium height, with a round face and light hair. He always looked cheery, and he seemed to be a perfect specimen of physical health. We liked him too. He was willing to work, and used to clean the floors in the ward; did it well too, and as though he enjoyed doing it.

I saw a good deal of him, for he played cribbage, which was also a favorite game of mine. Oh yes, he would manage to do this. He used the sign language, and we developed quite a code. When this man had anything special to say, he wrote it down. I remember that we used to ask him when he would talk again. The question did not seem to upset him. He simply smiled, and wrote down on his paper: "When the robins come again."

The doctors, knowing that there was no physical reason for his condition, finally gave him an intravenous injection which set him to talking, and he then explained that if he were to speak some terrible catastrophe would come upon the world. After the effects of the injection had worn off, he lapsed into silence again. But now the doctors understood what lay back of his refusal to talk, and were able to work on him, and finally they convinced him that no calamity was impending. (185-6)

Finally, however, I settled down. But not in a very satisfactory manner. I talked more, I played dominoes and checkers with the other men, I smiled occasionally. I became more or less content with hospital life. I stopped being restless, I no longer wondered, "When do we leave?"

In fact, I had reached a bland, mellow state which doctors fear for their patients. I became what is known as "hospitalized." At any rate I made a good beginning in that direction.

To be hospitalized indicates that a patient is improved, and is becoming well adjusted—that is, to hospital life. Indeed he becomes so well adjusted that he no longer wishes to leave—at least, not for the present. He keeps putting the idea off to some future day, when perhaps—perhaps he will do something about it. If it isn't too much trouble.

But what he really wants to do is to remain within the warmth and safety and security of the hospital. And while he is in this mood, he is not ready or fit to live anywhere else either. (196-7)

But—no jobs. Well, I said to myself, if I can't find a small job and make a little money, then I shall work out a big idea, and make a lot of money. Maybe that doesn't seem logical to you, but it appeared quite reasonable to me at that time. It was the logic of desperation.

I thought: "If I could only patent something." Some simple article that was useful and inexpensive, like paper clips or hooks and eyes. I had read of the fortunes made from simple articles. Something like that, I reasoned, would be the answer to all my problems. I would make a lot of money, and my troubles would be over. I would go down in history as a great inventor and a man of great renown. I would achieve fame and fortune for my loved ones. (199-200)

No one thinks it strange that a person who has been physically ill is weak for a long time afterward; but any sign—even the least—of nervousness or instability in a one-time mental patient is regarded as proof that he is still "insane." And by "insane" most people mean maniacal, raving, entirely befogged and unquestionably homicidal. At least that suspicion is always present. (211)

"Procrastination is one of the forerunners of insanity. This began in a mild way in the West—but only at times. After coming back home, it set in in earnest. It was not chronic insanity as yet, but mental fatigue, a mind that was breaking down from years and years of worry and disappointments; the beginning of a different view of life; the beginning of self-accusation; the beginning of self-pity; the beginning of a pronounced introvert; the beginning of failure. Still, up to that time I had done no wrong. The events after that were the workings of a mind gone astray." (I refer to my business mistakes, and my moroseness.) (226)

Finally I want to say again that it is useless ever to advise anyone who is breaking down mentally to "snap out of it," He needs help, not advice. If he could "snap out of it" just for the wishing, he certainly would do so. (240-1)

|