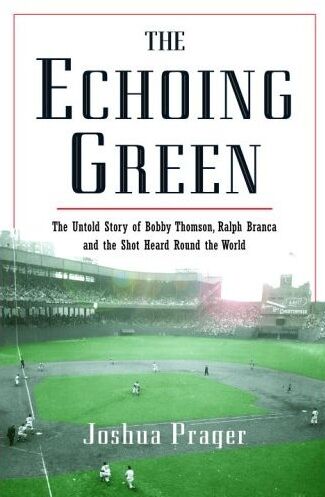

The Echoing Green

Joshua Prager (2006)

"As long as I've got a chance to beat you," Durocher later wrote in his autobiography, "I'm going to take it. I don't care if it's a zillion to one." (8)

It takes about two-fifths of a second for a ball to whirr from pitcher to catcher. And some twenty seconds pass between each of the 280-odd pitches in every game. In that window, players and coaches communicate strategy. Some of it, like where to position a fielder, is gesticulated for all to see, barked for all to hear. But most is dog-whistled, silent directives the opposition tries to detect then decipher. Among these are orders on everything from when to run to when to swing, when to bunt to what pitch to throw, secret instruction given ballplayers in a blur of filliped fingers, tugged earlobes, swiped cap-bills, adjusted pant legs and any other motion that may furtively convey the whim of the manager. These have included the blow of a nose, the covering of a crotch, the direction of spit saliva.

Signs often hinge on an "indicator"—a motion usually indicating that the next signal given will determine the play. The indicator and the ensuing signal can get quite complicated. Consider the system used by the Texas Rangers in the early 1970s. . . .

Signs often hinge on an "indicator"—a motion usually indicating that the next signal given will determine the play. The indicator and the ensuing signal can get quite complicated. Consider the system used by the Texas Rangers in the early 1970s. . . .

The Texas batter peered at his third base coach, who mid-gesticulation swiped either his cap, his jersey, or his legs. If he touched the cap, the very next sign he gave was the one to follow. If he touched the jersey, the second sign was the one. If he touched his legs, it was the third.

Now the batter looked for the specific instruction. If the coach then went to his cap, the batter was to bunt. If he touched his face, the hit-and-run was on. If he touched his jersey, the runner was to steal. If he touched any place else on his body—a "dead spot" such as his elbow or belt—the batter was on his own.

Furthermore, each play had several variations. Where on his cap the coach touched determined what kind of a bunt was expected of the batter. If the coach touched the bill of his cap, the batter was to lay down a regular bunt. If he touched the front of the cap, the batter was to attempt a squeeze. If he touched the top of the cap, the batter was to try to bunt for a hit. (29-30)

Chapter 136, Section 21 of Massachusetts law stated that sports were not to be played outdoors on Sundays before 1:30 p.m. And so a contest that having swayed this way or that would have forever tipped a pennant race was instead stopped, a footnote lost to time. (111; fucking Puritans)

On June 14, 1949, a fan named Ruth Ann Steinhagen, nineteen, had shot Eddie Waitkus in the chest with a .22-caliber rifle in room 1297-A of the Edgewater Beach hotel in Chicago. (The incident inspired Bernard Malamud to write his 1952 novel The Natural.) (113)

Jacobellis raised his Speed Graphic to his glasses. He focused—thirty men framed beneath seven clubhouse windows—then pressed down his right index finger, the spirit of a team preserved. Here was Mays, the only player holding his glove, the Rawlings Mort Cooper slipped between jersey and forearm. Here were Durocher and Franks side by side and unsmiling. And here, six feet above the cap of Davey Williams, was a window within a window, a rectangular hole in wire mesh fittingly preserved in team portrait. Unknowingly, a freelance photographer had documented the secret of a team. (186)

Home team, then away, took batting practice, the park's loudspeakers serenading each with a carefully chosen song: "It's the Loveliest Night of the Year" for New York, "Enjoy Yourself. It's Later Than You Think" for Brooklyn. (192)

[Sal "The Barber"] Maglie warmed up "as nonchalantly as if this were just a World Series," joked Bill Roeder in the New York World-Telegram and Sun, and Gordon McClendon leaned into his microphone. "Twenty years from now, the fans will be talking about this afternoon's hero as yet unknown," McClendon told his audience. "If there is a goat, his name will echo down the corridor of time." (195)

In the second, Maglie retired the Dodgers in order, and with one out in the bottom of the inning, Lockman singled off Newcombe. From his perch in the fourth window of the clubhouse, Franks watched a tiny Thomson walk to the plate. He knew that Thomson was squarely in the wanting-the-signs camp. And as Newcombe peered in for his sign, so did Thomson, looking beyond second baseman Robinson toward the bullpen. Says Thomson, "I don't know why I wouldn't have." (197)

Playoff or not, no barb was off limits when Brooklyn faced New York. Robinson, though a gentleman, cracked about Laraine Day. Durocher, though a friend of integration, screamed racial obscenities. Outfielder Earl Rapp remembered to author Harvey Rosenfield a talk Durocher gave his black players before facing Brooklyn on August 14. "If the game gets close and tense," Durocher told them, "I may be shouting 'nigger' and 'watermelon' at guys on the other side like Jackie Robinson. But I want you guys to understand that you are on my team." (201)

Not once in baseball's 278 preceding playoff and World Series games had a team overcome a three-run deficit in a ninth inning. (Nor, at this writing, has any team in the 879 subsequent such games.) (206)

Hodges, his voice high, hysterical, continued to scream. "Bobby Thomson hits into the lower deck of the left-field stands! The Giants win the pennant! And they're going crazy! They're going crazy!"

No one could say anything just once. As Thomson hit first, Stanky shot from the dugout toward Durocher, the second baseman calling out, "We did it! We did it! We did it!" Pafko, confetti flittering down about him, spoke to a wall that had given no carom: "It can't be! It can't be! It can't be!" Behind the Brooklyn dugout, a girl of eighteen in tears named Terry O'Malley turned to her father, owner of the Dodgers: "Oh, Pop! Oh, Pop! Oh, Pop!" And Chadwick [the electrician and Brooklyn Dodger fan who nevertheless was hired to install a secret signal buzzer system for the Giants], supine before his wife and daughter, repeated over and over: "I can't believe it. I can't believe it. I can't believe it." (222)

He who minutes before had peered through a telescope at Rube Walker's white fingers now held in his own a paper cup brimming with scotch. Franks was drunk. "I'm too upset to"—the coach paused, his words slurred. "I, I just don't know what the." Aro moved on and the intoxicated Franks, noted Ed Sinclair of the New York Herald Tribune, "sagged against a pillar and sobbed unrestrainedly." Bill Rigney approached his coach. "Why are you crying, Herman?" he asked. "Damned if I know," answered Franks. (235)

And so it was that Branca and Thomson came together. He who had lost stated he had done his job well. He who had won stated he had done his job poorly. In the aftermath of a home run, pitcher and hitter, by dint of disposition and fortuity, were strangely in step. (239)

On October 13, 1972, Richard Nixon welcomed the pair to Washington. The ballplayers would in twenty-five days vote for the president a second time. But the budding scandal dubbed Watergate displeased even Republican Thomson and, steps from the Oval Office, he turned now to a presidential aide. "I said, 'I don't like reading all this stuff in the paper,'" recalls Thomson. "I said why don't they do something about it, get it off the paper and get rid of it as a story? He said the president is making his own study of it. I wasn't satisfied with that. . . . Get it out, get it off the table, admit it. Why kid yourself?"

Fifty-six days after Nixon resigned his office, Thomson, fifty, chose to keep quiet a heist. (326)

That rumors continued to profane the miracle nettled Thomson. "It's reared its ugly head every once in a while," he says. And it was now, on its thirtieth anniversary, that a phone call from another reporter had the perpetrator again swearing to its sanctity. "No," Thomson told the Los Angeles Times. "I had no help from any illegal sign-stealing on the homer." Branca in turn told reporter Earl Gustkey that he had no desire to speak of the playoff, that over the years he had "talked about that day so much it was like the water was up to my nostrils." But goat then stepped from the gangplank. "The Giants cheated and stole the pennant in 1951," said Branca, "and that's the truth." And so page 11 carried word of a buzzer, word that just as Thomson had pulled a fast one—lining to left a fastball—so had a miracle team. (329-30)

Not all those I contacted were helpful, baseball fan Fidel Castro not caring to share if he recollected the game., Brooklynite Bobby Fischer willing to reminisce only for $200,000. Even some central to my book, like Ann Branca and Franks, were tightlipped, the otherwise gracious coach not so much as acknowledging to me a telescope. "I don't know anything about it," he said. Wife Ami laughed: "Oh, Herman!" (356-7)

|