DINO: Living High in the Dirty Business of Dreams

Nick Tosches (1992; rpt. 1999)

Read anything by Nick Tosches. That goes double for DINO: Living High in the Dirty Business of Dreams. It's Tom Wolfe-ish biographical art as practiced by Jim Thompson:

The old-timer taught Gaetano the trade. He told him too about the new law that had been passed just months earlier, the law that said men must now pay tax on what they earned; and he explained, as it had been explained to him, that they were among the more fortunate ones as far as this new income tax went, for they were not payroll workers like those in the mills; theirs was a business of coins, which none but them tallied. [12].

Tripodi was the first of many such characters whom Dino would encounter in his life: men—America called them the Mafia—who sought to wet their beaks (fari vagnari u pizzu, as the Sicilians said) in the lifeblood of every man's good fortune [51].

Those close to him could sense it: He was there, but he was not really there; a part of them, but apart from them as well. The glint in his eye was disarming, so captivating and so chilling at once, like lantern-light gleaming on nighttime sea: the tiny soft twinkling so gaily inviting, belying for an instant, then illuminating, a vast unseen cold blackness beneath and beyond. The secret in its depth seemed to be the most horrible secret of all: that there was no secret, no mystery other than that which resides, not as a puzzle to be solved or a revelation to be discovered, but as blank immanence, in emptiness itself. [54-5].

He was born alone. He would die alone. These truths he, like every punk, took to heart. But in him they framed another truth, another solitary, stubborn stone in the eye of nothing. There was something, a knowing, in him that others did not apprehend. He was born alone, and he would die alone, yes. But in between—somehow—the world in all its glory would hunker down before him like a sweet-lipped High Street whore. [55].

They used to make love and laugh. Now they fucked and fought. How long, after all, could butterflies live? Love was a racket. It was like booze. It exhilarated you, it transported you, and in the end it fucked you over and left you feeling like shit. [99].

It was hard to keep track of Dean's kaleidoscopic love life. "He fell in love with Jeannie, and it was a storybook romance," Jerry [Lewis] would say. "We were playing in Baltimore, and he was driving all night to Cumberland, Maryland, where—wait a minute: have I got the wrong broad? I have the wrong broad. What the hell was her name? This was another chick he was goin' with that he almost married." There was a song. Ivie Anderson had sung it with Duke Ellington back in 1936; it had been in the air that rainy springtime when Dean and Ross Monaco had come west with Joe DiNovo: "Love Is Like a Cigarette." Maybe that was what it came down to: a bad habit; a few drags of pleasure followed by a lousy taste. You put one out, you started another. Every once in a while, you coughed, you dumped the ashtray and said fuck it. [186]

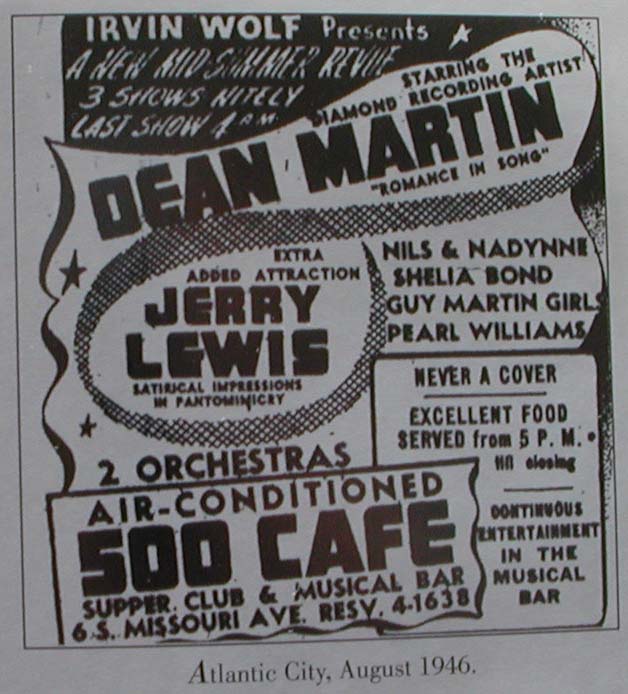

The sophisticated, white-collared, and well-heeled New York Times itself, in an article published while Martin and Lewis were in Las Vegas, hailed their "refreshing brand of comic hysteria," their "wild and uninhibited imagination." And yet, these few years later, the nature of that appeal is as alien and as difficult to translate as the language, syntax, and meter of Catullus. There are no films or tapes of their nightclub act. Only secondary fragments have survived to be judged . . . none of them predating 1952. Those fragments convey almost nothing of the dazzling appeal of that hilarity proclaimed in contemporary accounts. And yet the howling laughter present in many of those fragments, in the radio shows and television performances, all done before live spectators, is unanswerable. Those spectators, who had lined up for free shows at network studios, were not the same urbane nightclub-goers who howled at the Copacabana or Chez Paree or the Flamingo. Their sense of yockery was perhaps homelier; but, on the other hand, it was less primed by booze. Jerry was right: Martin and Lewis appealed to everyone. But why? [204]

"Let us not be deceived," the New York Times had declared in April 1947, while Dean and Jerry had been playing at the Loew's Capitol; "we are today in the midst of a cold war." . . . —but America wanted nothing more than to be deceived. Martin and Lewis gave them that: not laughter in the dark, but a denial of darkness itself, a regression, a transporting to the preternatural bliss of infantile senselessness. It was a catharsis, a celebration of ignorance, absurdity, and stupidity, as meaningless, as primitive-seeming, and as droll today as the fallout shelters and beatnik posings which offered opposing sanctuary in those days so close in time but so distant in consciousness. [204-5]

Newsweek dismissed [My Friend Irma Goes West] as "light-fingered malarkey." [221]

At one point, Glucksman had suggested to Dean that they should have lunch and get to know one another better.

"Nobody gets to know me," Dean told him. There was no smile, no anything; just those words. [226]

That was what Dean loved about golf: One could be with other men but apart from them, in silence in the open air. The driver clubface and that little white rubber-cored ball barely met: 450 millionths of a second, that was it. It was the sort of contact Dean liked. [226]

Bosley Crowther's colleague at the New York Times dismissed the picture as a "consignment of corn." [233]

The early 1950s belonged to them. It was the age of television, of whitewalled, tail-finned mindlessness; a world gone mad with mediocrity. [245]

Jerry Lewis said it all: "Can you pay two men $9,000,000 to say `Did you take a bath this morning?' `Why, is there one missing?'—do you dare contemplate such a fuck-and-duck? Yet that's what we did. We did that onstage, and they paid us $9,000,000." [246]

That Herald Review review of Scared Stiff had been an anomaly. Not that it had held forth a kind word for Dean—it had not. But it had found Jerry unbearable. And that is the way Dean now found him: an overbearing egomaniacal obnoxious fucking Jew who was pushing thirty and still playing a thirteen-year-old palsied monkey and seeing it as fucking genius. [268]

[For Dean] there could be no happiness but in waving away the world; none but in being apart, unthinking, unfeeling. [281]

He needed something new, something different. "Memories Are Made of This" was pure romance; and Dean, who hated memory itself, whose marriage had once again turned to shit just two weeks before, wove it into a lie of gold. [282]

When Dean read the script, he came to Jerry in a rage.

"A fucking cop, hey?"

"That's right. A cop."

"I'm not playing a cop." [287]

Asked if it was true that he had objected to Jerry's desire to inject "pathos and heart" into their work, Dean said he would not have objected "if he knew how to do it." [297]

The role of Bama "was a snap for me. I just played cards and talked Southern." He already spoke with a drawl in real life. God only knew where it came from, that added growth of obscuring kudzu he had cultivated around the wall of lontananza that kept the world at bay. No one else from Steubenville ever talked that way. Yet, like the Stetson he wore in the movie, it somehow fit him. [308-9]

Dean, whose company Sinatra constantly pursued, was not one to play the sycophant. He liked Sinatra, but he knew him for what he was: a half-a-mozzarella that never grew up. Joey, Sammy, and Peter Lawford were nobodies. They needed Sinatra, he did not. Sinatra had given him and MacLaine their parts in Some Came Running; but they likely could have gotten the parts without him. Maybe MacLaine, Frankie's quondam comare, wanted to be one of the guys; he did not. He watched Sinatra call Davis "a dirty nigger bastard" when Davis told an interviewer that Sinatra was capable of being impolite; he had watched Davis beg to be returned to his good graces. Dean neither gave nor took that kind of shit. Sinatra could be a pain in the ass in other ways, too. Little more than a year earlier, at Romanoff's on the Rocks in Palm Springs, Dean had had to drag him bodily away from Bill Davidson, a journalist who had written negative things about him. Why he even read the shit that people wrote about him was beyond Dean; that he let it get to him was ridiculous. He took it all so fucking seriously. He thought he was a fucking artist, a fucking god. But, again, at the same time, he liked Frank. Their families had grown close. They drank together. They gambled together. They laughed together. If people wanted to call him part of Sinatra's Clan, so be it, fuck it; it made no difference. [312-13]

Sinatra, who lusted to rub against any power greater than his own, threw himself fully into Kennedy's campaign. Reverting to the Bogart days, the Clan became the Rat Pack, the sideshow of Kennedy's privileged Democratic dream. Kennedy was a glamour boy. He enjoyed being around celebrities, as Sinatra enjoyed being around power. The two of them waxed dreamy-eyed round each other. [313-14]

"Watching his special color show last evening," [columnist Harriet Van Horne] wrote, "I had the feeling that this pretty laddie with the careful ringlets and roguish grin would take great pleasure in spitting in the eye of the audience. His offhand air, his apparent lack of rehearsal and his highly personal ad libs all bespeak a faint contempt for his work."

On the other hand, Van Horne found the CBS production of For Whom the Bell Tolls to be "a massive accomplishment."

But for every Van Horne there were thousands of others who loved what Dean was doing. He was not spitting at them; he was spitting for them. His message was clear: All this fake-sincerity shit that was coming through television—not only through television: the newspapers, the pictures, every politician's false-faced caring word and grin—it was all a racket. It was a message that appealed to the menefreghismo in every heart: Fuck it all; eat, drink, and be merry, for even Sorelli the Mystic knew not what tomorrow might bring. [315-16]

In May 1958, Dean hosted the SHARE Boomtown party for Jeanne at the Moulin Rouge, where he was lowered to the stage seated astride a white saddle on a chandelier. [317]

Sinatra and Martin: There was something about them that brought out the biggest gamblers. . . . It was not just the dirty-rich giovanostri and padroni who were drawn to them, to their glamour, to the appeal of darkness made respectable. The world was full, it seemed, of would-be wops and woplings who lived vicariously through them, to whom the imitation of cool took on the religiosity of the Renaissance ideal of imitatio Christi. The very songs that Sinatra and Dean sang, the very images they projected, inspired lavish squandering among the countless men who would be them. [323]

"High Hopes," with new lyrics tailored by Sammy Cahn, would become Kennedy's campaign song. Along the way, it would become the anthem of a time's dumb optimism. [324]

On that same night of July 13, as Kennedy's nomination was being announced, Dean opened at the Sands.

"I'd like to tell you some of the good things the Mafia is doing," he said. There was a momentary hush, then a long, slow wave of rising laughter.

His singing had begun to take on a new tone. He was no longer merely selling the lie of romance. Stabbing sharply and coldly here and there into the songs with lines of wry disdain, he was exposing his own racket as well, selling the further delusion of their sharing in the secret of that lie itself. It was an elaboration on his tried and true style of singing to the men rather than the women, of singing to them as if they alone could truly understand him. It was also a natural emanation of the way he felt. He simply no longer cared. He began more songs than he finished, dismissing most of them with a wisecrack partway through. Some, with the help of lyricist Sammy Cahn, were simply reduced to gross parody.

"If you think I'm going to get serious, you're crazy. If you want to hear a serious song, buy one of my records." [329]

Cal-Neva was no longer of concern to Dean. After realizing the extent of Giancana's hidden involvement in the operation, he had pulled out. He knew Giancana's kind far better than Sinatra ever would. Where that kind wet their beaks, others went dry. [332]

Dean himself had known Marilyn since early 1953, before Sinatra had met her, before DiMaggio had married her. It seemed that everybody—man, woman, and beast—wanted to fuck her. But her sexiness was only desperation. It had been in her eyes for years: death like a Valentine. [335-6]

Sinatra continued to entertain delusions of his place in Camelot. The door of a guest room at his Palm Springs home bore a plaque with Kennedy's name on it. He had gone so far as to have a heliport constructed on his estate, in preparation for an anticipated presidential visit in March. Cottages were added for the Secret Service. There were extra telephone lines installed, a flagpole erected. It was fucking ridiculous.

. . . on February 27, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy received a memo from Director J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI. During its investigation of Johnny Rosselli, the Bureau had been led to Judith Campbell, whose telephone records, in turn, had revealed several calls to President Kennedy's personal secretary at the White House, as well as to Sam Giancana in Chicago. Bobby advised his brother, increased his surveillance of Giancana, and called Peter Lawford: JFK would have to steer clear of Sinatra, who was obviously the catalyst in the Kennedy-Campbell-Giancana triangle. On his trip west in March, the president would stay at Bing Crosby's home. Lawford would have to break the news to Sinatra.

"Frank was livid," Lawford said. "He called Bobby every name in the book." When Lawford left, Sinatra's butler watched him go at the heliport with a sledgehammer.

The message and the messenger were one. As far as Sinatra was concerned, that was the end of Lawford. [341]

Sinatra himself headlined the opening of the new Cal-Neva on June 29. Dean opened there a month later, on July 27. Marilyn Monroe came to Cal-Neva on both occasions. On the first, she overdosed on pills and booze. On the second, wandering around in a ghostly stupor, she spoke to Skinny D'Amato of things of which, as he told her, people ought not to speak. Dean knew what was wrong with her, beyond the pills, beyond the whole endless lost-little-girl thing: She just could not handle the dirty knowledge into which she had wandered, the black forest of Sam Giancana and Johnny Rosselli and her darling scumbag Kennedys, that world that lay past the dreamland she had shared with those who paid to see her. She wanted back into the fairytale, but there was really no way back. Dean knew things that people would not believe, things about the government sucking up to men such as Rosselli and Giancana, dealing with them in death, while others in government persecuted them; things about the black knights and the white knights fucking the same broads, drinking from the same bottle, and sharing the same spoils and murderous plots. Marilyn had glimpsed these things through her own errant innocence, and they had terrified her. The great temptress had finally encountered a few wisps of what really lay in the garden of temptation. Dean could see it: She was not long for this world. If she did not shut her mouth, she would not even need the pills to take her where she was going. [344-5]

The body was no longer what it once had been: excrescences, aches, and skin like brittling caul. Mortality's inklings grew deeper; the flesh became a stranger's. On the fourth day of the new year, at Cedars of Lebanon hospital, he had a cyst removed from his left wrist. On January 22, when he opened with Sinatra at the Sands, he felt like an old man. They were billed as Dean Martin & Friend. They had their own bar cart onstage. The drunk routine was becoming less of an act and more of a hoked-up burlesque of drab reality. For years, he had been a man of moderation: a few drinks during the day, a few more and maybe a sleeping-pill at night. Now the nights were getting darker. Look at Sinatra: this guy wanted to be a kid forever. What more could one ask of life than a bottle of Scotch, a blowjob, and a million bucks? And Dean Martin had it. Why then did he go on? He was not like Frank; he got no thrill from this shit, being onstage, hearing himself on the radio, seeing himself ten feet tall on a screen. But he did not wonder long. Maybe it was like the philosopher said: Life was but a dream betwixt the cradle and the grave, and the less one pondered, the longer and more soundly he abided. Something like that. [358]

It was in late January that he first heard of them, along with just about everyone else in America. What a silly name: Beatles, with an a. "I Want to Hold Your Hand" appeared on the Billboard charts the week that he and Sinatra opened at the Sands. Their old label, too: Capitol. Frank, Dean, Sammy, and Peter; John, Paul, George, and Ringo. Everything changes, nothing abides. Who ever thought the day would come when America would buy back its own sense of cool secondhand from England? The days grew strange. [359]

The Beatles had by now had four number-one hits in as many months. All twelve-year-old Dino Jr. could talk about was the Beatles: the Beatles this, the Beatles that, she-loves-you-yeah-yeah-yeah-yeah. Dean got sick of it. "I'm gonna knock your little pallies off the charts," he told the kid. [364]

In mid-August, "Everybody Loves Somebody" knocked the Beatles' "A Hard Day's Night" out of the number-one spot to become the biggest record in America. Two weeks later, it appeared on the pop charts in the Beatles' homeland as well. Little Dino Jr. beheld the old man in amazement. [364]

The Silencers, [Stella Stevens] remembered, "was the first time I had my dress ripped off in a film." [372]

"If Dean Martin in his first show," said The Christian Science Monitor, were any more relaxed, he'd fall on his face. Many of his opening remarks and jokes had to do with drinking. One wondered, watching Dean, whether this man cared whether his show went over or not."

But "The Dean Martin Show" was an immense and immediate success. His uncaring manner and good-natured boorishness endeared him to the millions who were sick of sincerity, relevance, and pseudosophistication. Dean was a man whose success and fortune no man begrudged him. He seemed somehow kindred, one of them but blessed beyond them by the Fates. In him, for one late hour before the final day of every workweek, the multitudes, tired and half-drunk and onward-slouching, found something of their own: lullaby and vindication, justification and inspiration, a bit of boozy song, and a glimpse of gal-meat. [373]

For Henry Miller, as for the masses of sub-literate and post-literate slobs who comprised the vast heart of Dean's viewership, Dean was the American spirit at its truest: fuck Vietnam, fuck politics, fuck morality, fuck culture and fuck the counterculture, fuck it all. We were here for but a breath; twice around the fountain and into the grave: fuck it. [374]

At a booth near their table sat Frederick R. Weisman, the fifty-four-year-old director of the board and former president of Hunt's Foods, and Franklin H. Fox, a businessman from Boston. The two men were about to become fathers-in-law through the marriage of their children, and they had come from dinner at Chasen's to have a drink together. They found the noisy vulgarity from the nearby table offensive. Weisman leaned over and commented to Sinatra that there were other people present in the room.

"You're out of line, buddy," Sinatra told him. Then Sinatra took a good look at him and, turning back to Dean and the others, muttered something about "this fucking Jew bastard." Weisman objected. The next thing Dean knew, he was pulling Sinatra off the fucking Jew bastard, who was now talking about dirty wops. When Dean heard that, he rapped him in his fucking Jew-bastard face with his dirty-wop fist. A table broke as Weisman went down. Then Dean, Sinatra, and the others were out of there, while Fox tried to help Weisman off the floor.

Twenty-four hours later, Weisman was still unconscious in the intensive-care unit of Mount Sinai Hospital. On Friday, June 10, in critical condition and not expected to live, he underwent two and a half hours of cranial surgery to alleviate the effects of a skull fracture. . . . Chief Anderson, who had questioned Dean and Sinatra concerning the incident, reported Dean's contention that "he hadn't seen a thing." The investigation was closed on June 30, with no charges pressed. [375-6]

Texas Across the River made money, too. Both [that and Murderers' Row] were among the sloppiest and most witless pictures of a sloppy and witless era. [378]

And Dean . . . in slow abdication, receded further into the shadow of his own unknowing. [380]

It was part of the image: the faithful family man beneath the vulgar abandon of the carefree boozer with the philandering eye. It was what made him acceptable. It was what endeared him. He reaffirmed the traditional values while flaunting them. His marriage of eighteen years and his old-world sense of family comforted his viewers while his good-humored blasphemy captivated them. They felt that difference between him and Sinatra, in whom, as a man, there was little for them to respect. This Christmas show illustrated that. Both families were supposed to have gathered, but Sinatra had not even been able to produce his latest wife, Mia Farrow, a simpering little flower child who was younger than his own daughter. [384]

As Dante, his Beatrice; so Dean, his Frostie Root Beer girl. Never under heaven had there been a truer love. His wealth and fame were as nothing; the beauty of his soul was all she craved. In the name of amore, she abdicated; in the name of amore, he bowed the knee of fealty to romance and eternal youth.

It lasted about three months. He waltzed around until March that way: like a fucking cafone with love-dust in his eyes. Then it got worse. [394]

On September 16, "The Dean Martin Show" began its seventh season. The sixties supposedly had been a baptism of liberation for America. Free love and free speech had sold well. But after all the Day-Glo debris, swami shit, and dead flowers were swept away, the puritan ethos emerged unvanquished. Beneath her new tie-dyed skirt, her whiter-than-white cotton panties remained undefiled. Now, however, her prudish tyranny governed not in the name of God and morality but in the name of sensitivity and liberty. That was the true legacy of the sixties' ideological boutique: censorship in the name of freedom. . . . Even the Ku Klux Klan was careful not to offend: "Every klansperson in Texas is invited," one Klan titan announced, eschewing sexism. Forced to tread gently among the myriad delicate whining isms of New Age sensitivity, the American language at last began to fulfill its promise as the world-voice of post-literate mediocrity. [401]

[On Martin's becoming a paid spokesman for AT&T:] As Dean himself explained, with a shit-eating grin on his face: "The telephone is something that is needed." [424]

|